- Department of Neurosurgery, Kumamoto City Hospital, Kumamoto, Japan

- Department of Neurosurgery, Kumamoto Rosai Hospital, Yatsushiro, Japan

- Department of Neurosurgery, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan

Correspondence Address:

Keishi Makino, Department of Neurosurgery, Kumamoto City Hospital, Kumamoto, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1094_2024

Copyright: © 2025 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Keishi Makino1, Seiji Tajiri1, Ryosuke Mori1, Akira Takada1, Yasuyuki Hitoshi2, Akitake Mukasa3. Cervical wart-like cutaneous appendage with a contiguous stalk of limited dorsal myeloschisis treated with untethering after long-term follow-up. 14-Mar-2025;16:87

How to cite this URL: Keishi Makino1, Seiji Tajiri1, Ryosuke Mori1, Akira Takada1, Yasuyuki Hitoshi2, Akitake Mukasa3. Cervical wart-like cutaneous appendage with a contiguous stalk of limited dorsal myeloschisis treated with untethering after long-term follow-up. 14-Mar-2025;16:87. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=13441

Abstract

BackgroundLimited dorsal myeloschisis (LDM) is a condition in which the separation of the neuroectoderm from the cutaneous ectoderm during primary neural tube formation results in localized disjuncture, causing a continuous cord-like connection and spinal cord tethering. We reported a case of cervical LDM with a wart-like cutaneous appendage that was treated with excision after long-term follow-up.

Case DescriptionThe patient was an 18-year-old girl. A wart-like cutaneous appendage was noted over the nape of the neck since birth. Computed tomography showed spina bifida in the cervical and thoracic spines, and spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a cervical skin lesion and an enlarged dural sac in the dorsal thoracic spinal cord. At 18 years of age, the patient occasionally experienced numbness in her left hand and was referred to our outpatient clinic due to a new high signal intensity in the dorsal cervical spinal cord on a T2-weighted MRI. The MRI showed that a cord-like object was continuous intradural and dorsal to the spinal cord from a cutaneous lesion in the median cervical region, with a high signal in the same region. Symptomatic cervical spinal cord tethering due to a cord-like material was diagnosed, and the patient underwent resection. During surgery, the tract was removed from the cutaneous lesion into the dura mater as a single mass and untethered in the dorsal spinal cord. The histological diagnosis was a pseudo-dermal sinus tract with no luminal structures or neural tissue present, as the cord-like substance was connective tissue containing small blood vessels. Based on the neuroimaging and pathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with cervical LDM. Neurological symptoms improved postoperatively.

ConclusionHerein, we reported a case of cervical LDM that was treated after long-term follow-up. The patient’s symptoms improved immediately after surgery. Cervical LDMs are rare, and the timing of surgery for LDM should be considered according to the patient’s condition.

Keywords: Limited dorsal myeloschisis, Spinal dysraphism, Tethered cervical cord

INTRODUCTION

Limited dorsal myeloschisis (LDM) was first described as a distinct clinicopathological condition by Pang et al.[

LDMs are categorized based on their skin manifestations as saccular and non-saccular.[

Given its rarity, reports on long-term outcomes in patients with LDM are limited. Here, we describe a case of cervical LDM that became symptomatic; the patient was treated after 18 years of long-term follow-up.

CASE PRESENTATION

An 18-year-old girl was referred to our hospital for left-hand numbness. She was born at 33 weeks and 6 days of gestation and weighed 1800 g at birth. A wart-like cutaneous appendage with dimples was observed over the nape of the neck. Since there were no abnormal neurological findings, the patient was placed under observation. Neuroradiological examinations were performed at 1 year of age. Spina bifida was found in the cervical (C1–C5) and thoracic (T3–T5) spine on spinal computed tomography [

Figure 1:

Neuro-radiological imaging during follow-up. (a) Computed tomography showed spina bifida at the cervical (C1–C5) and thoracic (T3–T5) spine. (b) Mid-sagittal T2-weighted MRI of cervical spine at age 2. The arrow indicated the skin lesion. (c-e) Mid-sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the cervical spine at age 2 (c), age 10 (d), and age 14 (e). No obvious high–signal-intensity in the cervical spinal cord. MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

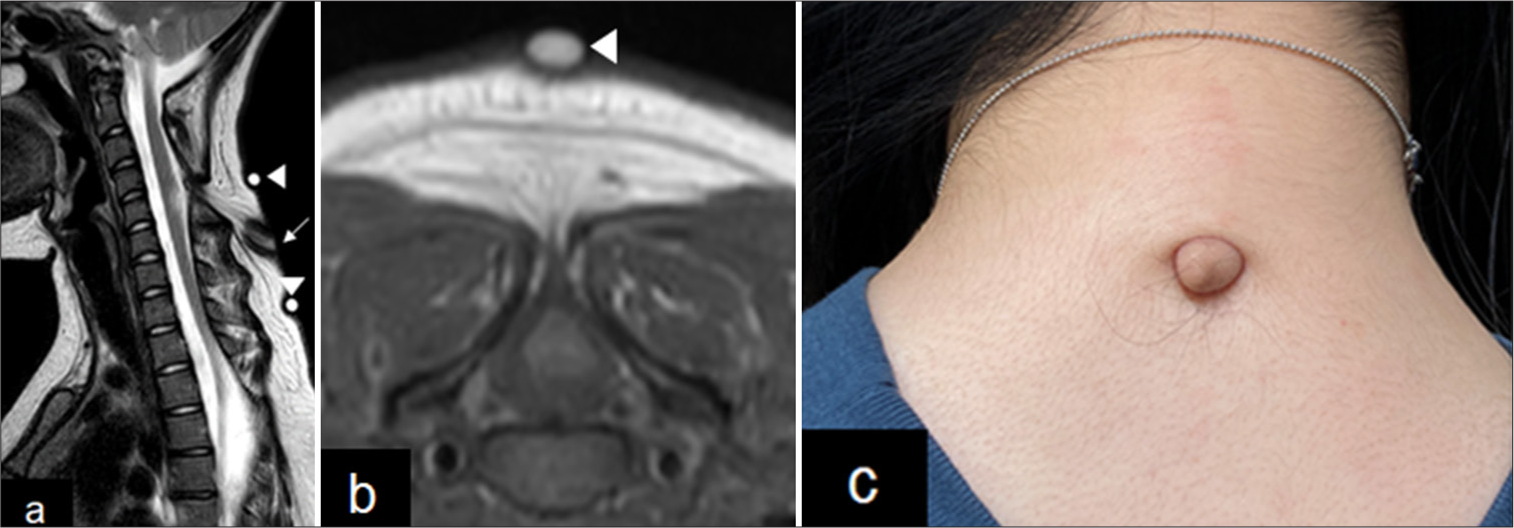

Figure 2:

Neuroradiological and photo-imaging of skin lesion. (a) Mid-sagittal T2-weighted MRI of cervical spine at age 18. The arrow indicated skin lesions, and arrowheads were landmarks of the skin lesion at the time of MRI examination. (b) Axial T2-weighted MRI at C5. The spinal cord is tethered posteriorly to the tract. The arrowheads are landmarks of the skin lesion at the time of MRI examination. (c) Photograph showing a wart-like cutaneous appendage over the nape of the patient’s neck. MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

Symptomatic cervical spinal cord tethering due to the cord-like material was diagnosed, and the patient underwent resection with monitoring of the somatosensory-evoked potential. A skin incision was made around the warts. We carefully dissected the tract and followed it all the way down to its penetration of the dura [

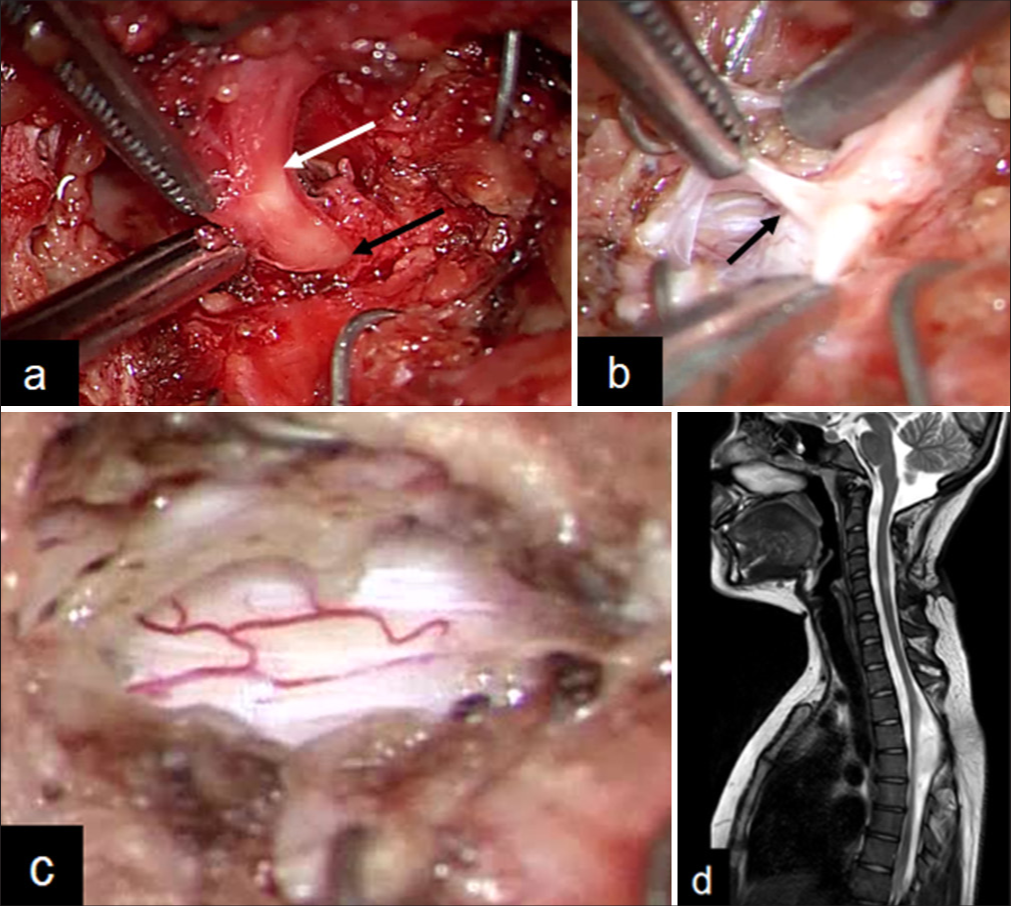

Figure 3:

Operative photographic views and MRI 6 months after surgery. (a) The subcutaneous stalk was continuous into the dura mater (white arrow: Subcutaneous tract; black arrow: Dural penetration). (b) The intradural tract is connected to the dorsal spinal cord (black arrow). (c) The intradural tract is untethered from the spinal cord. (d) Mid sagittal T2-weighted MRI of cervical spine 6 months after surgery. The high-signal legion was reduced at the dorsal cervical spine.

Postoperatively, the patient’s symptoms improved and did not present any new neurological abnormalities. MRI showed that the tethered spinal cord was released, and the high-signal lesion was reduced 6 months after surgery [

Histopathologically, the epidermal ridge was composed of a mixture of subcutaneous fat and connective tissue [

Figure 4:

Histopathological findings of the resected specimens. (a) Macroscopic image of the split surface of appendage (white arrow: Appendage, red arrow: Tract). (b) Macroscopic image of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained appendage (black arrow: Appendage, red arrow: Tract). The appendage contained mature fibroadipose tissue. The tract, composed of connective tissue containing small blood vessels, extends from within the subcutaneous fat tissue (H&E: ×12.5 (c), ×40 (d)). (e) Elastica van Gieson staining revealed that the tracts were composed of collagen fibers (×40).

Based on the neuroimaging and pathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with cervical LDM.

DISCUSSION

In this case, cervical LDM caused a tethered cord during adulthood. However, congenitally tethered cervical spinal cords are extremely rare in adults. In a few reported cases, it has been associated with a dermal sinus that enters the subarachnoid spaces and blends with dorsal spinal cord elements.[

In the case of the dermal sinus, the tract leads from the epidermis for a variable distance through the dermis, subcutaneous fat, fascia, muscle, vertebral arch, and meninges up to the spinal cord. Of these layers, only the epidermis and spinal cord are ectodermal in origin. Histological analysis of a typical dermal sinus tract revealed that this fistula had a lumen lined by stratified squamous epithelium immediately surrounded by dermal tissue.[

In this case, the cord-like structure was comprised of connective tissue containing small blood vessels and no luminal structures. Based on these pathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with LDM.

Cervical non-saccular LDMs are not commonly observed. Pang et al. described the distribution of cases by the types of LDM.[

Retrotraction and fixation of the cervical spinal cord seem to play important roles in flexion and extension movements in a relatively fixed spinal cord. This may explain the onset of symptoms in the adult age, where stretching and tension on neural tissues can occur with impairment of spinal circulation, leading to metabolic dysfunction, neuronal injury, and progressive neurological impairment.[

The patient underwent regular outpatient visits and MRI examinations. There were no symptoms during follow-up, and there was no abnormal signal in the spinal cord. However, when she experienced numbness in her left hand, a new high-signal-intensity lesion was found in the dorsal cervical spinal cord on T2-weighted MRI.

MRI is a noninvasive method used to monitor the pathological features of spinal cord lesions. Several histopathological studies of cervical spinal cord injury have reported that a blurred intramedullary high-signal intensity on T2-weighted images is thought to represent edema or petechial hemorrhage.[

Several studies have reported the preoperative relevance of MRI in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Morio et al. reported that patients with altered signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images demonstrated the worst postoperative prognosis compared with those who showed a preoperative signal change only on T2-weighted images.[

In this case, the patient was concerned about the cosmetic aspects of the neck lesion and numbness. During surgery for LDM with an appendage, untethering of the cord and cosmetic removal of the appendage should be performed during the same operation, as is typical for other tethered lesions with an appendage.[

CONCLUSION

Cervical LDMs are rare, and wart-like cutaneous appendages rather than saccular lesions are even rarer. Clinicians should be aware of possible morphological variations in skin lesions associated with LDM.

Author’s Contributions

K. Makino drafted the manuscript. S. Tajiri, R. Mori, A. Takada, and Y. Hitoshi were involved in the clinical care of the patient. A. Mukasa supervised the work.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Ackerman LL, Menezes AH. Spinal congenital dermal sinuses: A 30-year experience. Pediatrics. 2003. 112: 641-7

2. Karatas Y, Ustun ME. Congenital cervical dermal sinus tract caused tethered cord syndrome in an adult: A case report. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2015. 1: 15021

3. Maroufi SF, Dabbagh Ohadi MA, Hosseinnejad I, Tayebi Meybodi K, Takzare A, Ashjaei B. Cervical saccular limited dorsal myeloschisis, so-called “cervical myelomeningocele”: Long-term follow-up of a single-center series and systematic review. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2024. 33: 44-58

4. Mastronardi L, Elsawaf A, Roperto R, Bozzao A, Caroli M, Ferrante M. Prognostic relevance of the postoperative evolution of intramedullary spinal cord changes in signal intensity on magnetic resonance imaging after anterior decompression for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007. 7: 615-22

5. Menezes AH, Dlouhy BJ. Congenital cervical tethered spinal cord in adults: Recognition, surgical technique, and literature review. World Neurosurg. 2021. 146: 46-52

6. Morio Y, Teshima R, Nagashima H, Nawata K, Yamasaki D, Nanjo Y. Correlation between operative outcomes of cervical compression myelopathy and mri of the spinal cord. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001. 26: 1238-45

7. Morioka T, Suzuki SO, Murakami N, Mukae N, Shimogawa T, Haruyama H. Surgical histopathology of limited dorsal myeloschisis with flat skin lesion. Childs Nerv Syst. 2019. 35: 119-28

8. Morioka T, Suzuki SO, Murakami N, Shimogawa T, Mukae N, Inoha S. Neurosurgical pathology of limited dorsal myeloschisis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2018. 34: 293-30

9. Nishimura Y, Hara M, Natsume A, Wakabayashi T, Ginsberg HJ. Complete resection and untethering of the cervical and thoracic spinal dermal sinus tracts in adult patients. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2020. 82: 567-7

10. Ohshio I, Hatayama A, Kaneda K, Takahara M, Nagashima K. Correlation between histopathologic features and magnetic resonance images of spinal cord lesions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993. 18: 1140-9

11. Pang D, Zovickian J, Oviedo A, Moes GS. Limited dorsal myeloschisis: A distinctive clinicopathological entity. Neurosurgery. 2010. 67: 1555-79 discussion 1579-80

12. Pang D, Zovickian J, Wong ST, Hou YJ, Moes GS. Limited dorsal myeloschisis: A not-so-rare form of primary neurulation defect. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013. 29: 1459-84

13. Perrini P, Scollato A, Guidi E, Benedetto N, Buccoliero AM, Di Lorenzo N. Tethered cervical spinal cord due to a hamartomatous stalk in a young adult. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2005. 102: 244-7

14. Sarukawa M, Morioka T, Murakami N, Shimogawa T, Mukae N, Kuga N. Human tail-like cutaneous appendage with a contiguous stalk of limited dorsal myeloschisis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2019. 35: 973-8

15. Weprin BE, Oakes WJ. Coccygeal pits. Pediatrics. 2000. 105: E69

16. Wilkinson CC, Boylan AJ. Proposed caudal appendage classification system; Spinal cord tethering associated with sacrococcygeal eversion. Childs Nerv Syst. 2017. 33: 69-8

17. Yamada S, Lonser RR. Adult tethered cord syndrome. J Spinal Disord. 2000. 13: 319-23