- Department of Neuroscience, Philippine General Hospital - University of the Philippines, Manila, National Capital Region, Philippines.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_64_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Kevin Ivan Peñaverde Chan, Alaric Emmanuel Mendoza Salonga, Kathleen Joy Ong Khu. Decompressive hemicraniectomy for acute ischemic stroke associated with coronavirus disease 2019 infection: Case report and systematic review. 24-Mar-2021;12:116

How to cite this URL: Kevin Ivan Peñaverde Chan, Alaric Emmanuel Mendoza Salonga, Kathleen Joy Ong Khu. Decompressive hemicraniectomy for acute ischemic stroke associated with coronavirus disease 2019 infection: Case report and systematic review. 24-Mar-2021;12:116. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/decompressive-hemicraniectomy-for-acute-ischemic-stroke-associated-with-coronavirus-disease-2019-infection-case-report-and-systematic-review/

Abstract

Background: Decompressive hemicraniectomy (DH) has been performed for some cases of acute ischemic stroke in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection, but there is little information about the clinical course and outcomes of these patients.

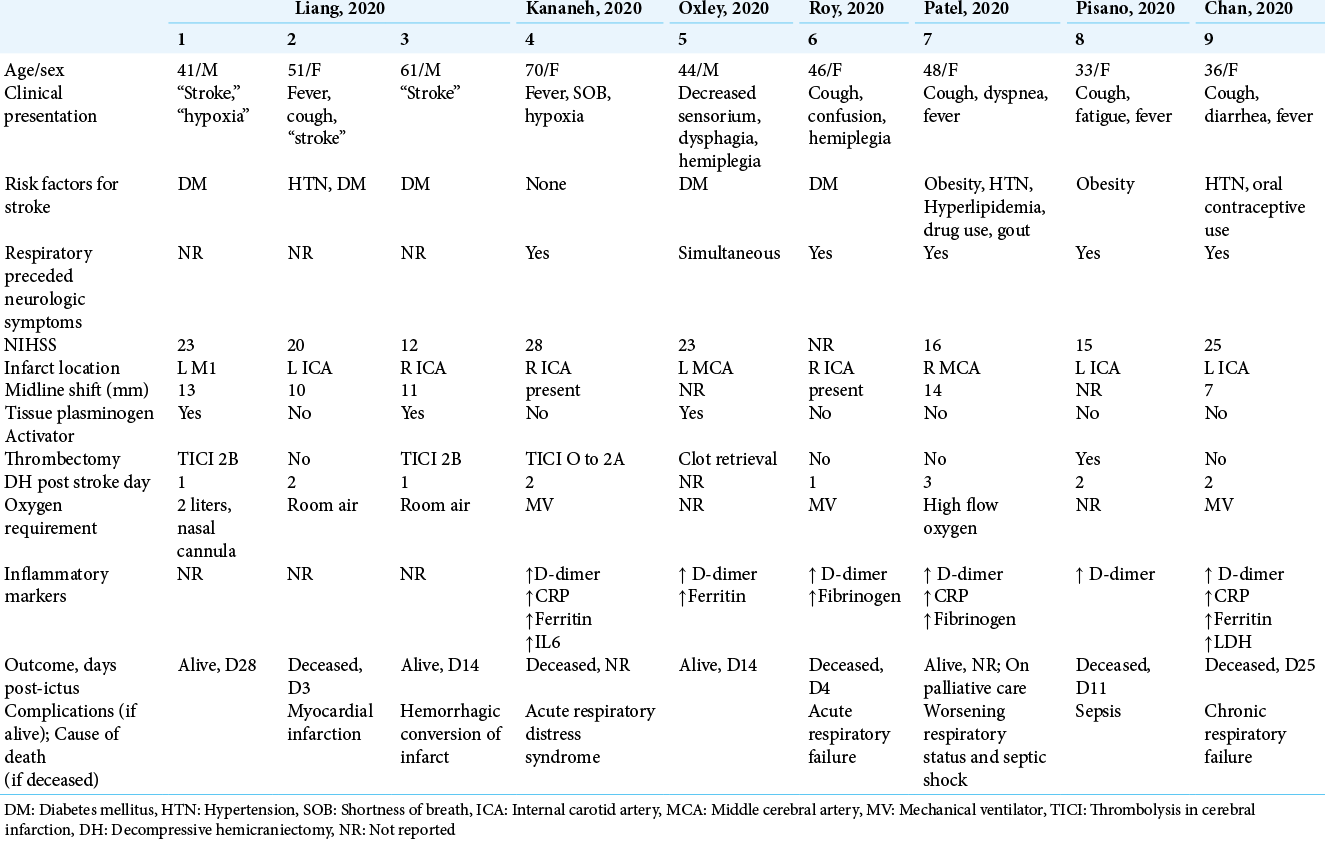

Case Description: We report a case of a 36-year-old woman with COVID-19 infection who developed stroke like symptoms while under home quarantine. Cranial CT scan showed an acute left internal carotid artery (ICA) infarct. She subsequently underwent an emergent left DH. Despite timely surgical intervention, she succumbed to chronic respiratory failure. A systematic review of SCOPUS and PubMed databases for case reports and case series of patients with COVID-19 infection who similarly underwent a DH for an acute ischemic infarct was performed. There were eight other reported cases in the literature. The patients’ age ranged from 33 to 70 years (mean 48), with a female predilection (2:1). Respiratory preceded neurologic symptoms in 83% of cases. The ICA was the one most commonly involved in the stroke, and the mean NIHSS score was 20. DH was performed at a mean of 1.8 days post-ictus. Only four out of the nine patients were reported alive at the time of writing. The most common cause of death was respiratory failure (60%).

Conclusion: Clinicians have to be cognizant of the neurovascular complications that may occur during the course of a patient with COVID-19. DH for acute ischemic stroke associated with the said infection was reported in nine patients, but the outcomes were generally poor despite early surgical intervention.

Keywords: Acute ischemic stroke, Coronavirus disease 2019 infection, Decompressive hemicraniectomy, Infarct, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is primarily a respiratory illness that is responsible for the ongoing pandemic around the world.[

In the pre-COVID period, patients who had a large-vessel ischemic stroke that caused significant edema and were refractory to medical management would be offered decompressive hemicraniectomy (DH). However, because of the novelty of COVID-19, there is scarce data on whether COVID-19 infection should be factored into the surgical decision-making process for hemicraniectomies, given that severe strokes were typically associated with poor prognosis.[

In this paper, we report the case of a 36-year-old woman who underwent DH for an acute infarct in the left internal carotid artery (ICA) distribution several days after being diagnosed with COVID-19 infection. We also review the relevant literature.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 36-year-old right-handed woman presented with a few days’ history of cough, diarrhea, and fever. Medical history was significant for hypertension and polycystic ovary syndrome, for which the patient took anti-hypertensive medications and oral contraceptives. A nasopharyngeal swab showed that the patient was positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The patient was prescribed Azithromycin and sent home to quarantine.

On the 8th day of home quarantine, the patient was found to have right-sided weakness and facial droop and was brought to the emergency department 8 h post-ictus. She had sustained wakefulness and was able to localize to pain, and her pupils were equal and briskly reactive to light. She also had hemiplegia and right central facial palsy. The NIHSS score was 25. Cranial CT scan showed a hypodensity at the left ICA territory without midline shift and an Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score of 0 [

Figure 1:

Axial images of initial 8-h cranial CT scans showed a dense left MCA sign (a) and hypodensity in the left ICA distribution (b). 24 h CT scan showed increased degree of hypodensity in the left ICA distribution and midline shift to the left (c). Postoperative CT scan showed a large left-sided craniectomy defect.

A 24-h monitoring CT scan showed an increased degree of hypodensity in the left ICA distribution, as well as a midline shift of 7.3 mm. In view of this finding, DH was recommended, but there was no consent. Shortly after, the patient was found to have tachycardia, labored breathing, and decrease in sensorium. She was only able to open her eyes to painful stimuli and withdraw to pain, and her left pupil became dilated. She was intubated, and then brought to the operating room for DH after consent was secured. Postoperatively, the patient’s sensorium improved, and she was able to open her eyes to speech and localize to pain. The anisocoria was reversed.

However, the patient continued to have fever, tachycardia, and tachypnea despite ventilatory support. Chest radiograph showed bilateral pneumonia with consolidation. The levels of the inflammatory markers D-dimer and CRP were higher than on admission, and ferritin and LDH levels were elevated as well. After 2 weeks, a repeat nasopharyngeal swab showed that the patient was negative for SARS-CoV-2. A tracheostomy was performed.

Over the course of her ICU stay, the patient also developed ventilator-associated Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia and pulmonary tuberculosis. She had persistent desaturation and hypoxia, making it difficult to wean her off ventilatory support. The patient succumbed to chronic respiratory failure 25 days post-ictus.

METHODOLOGY

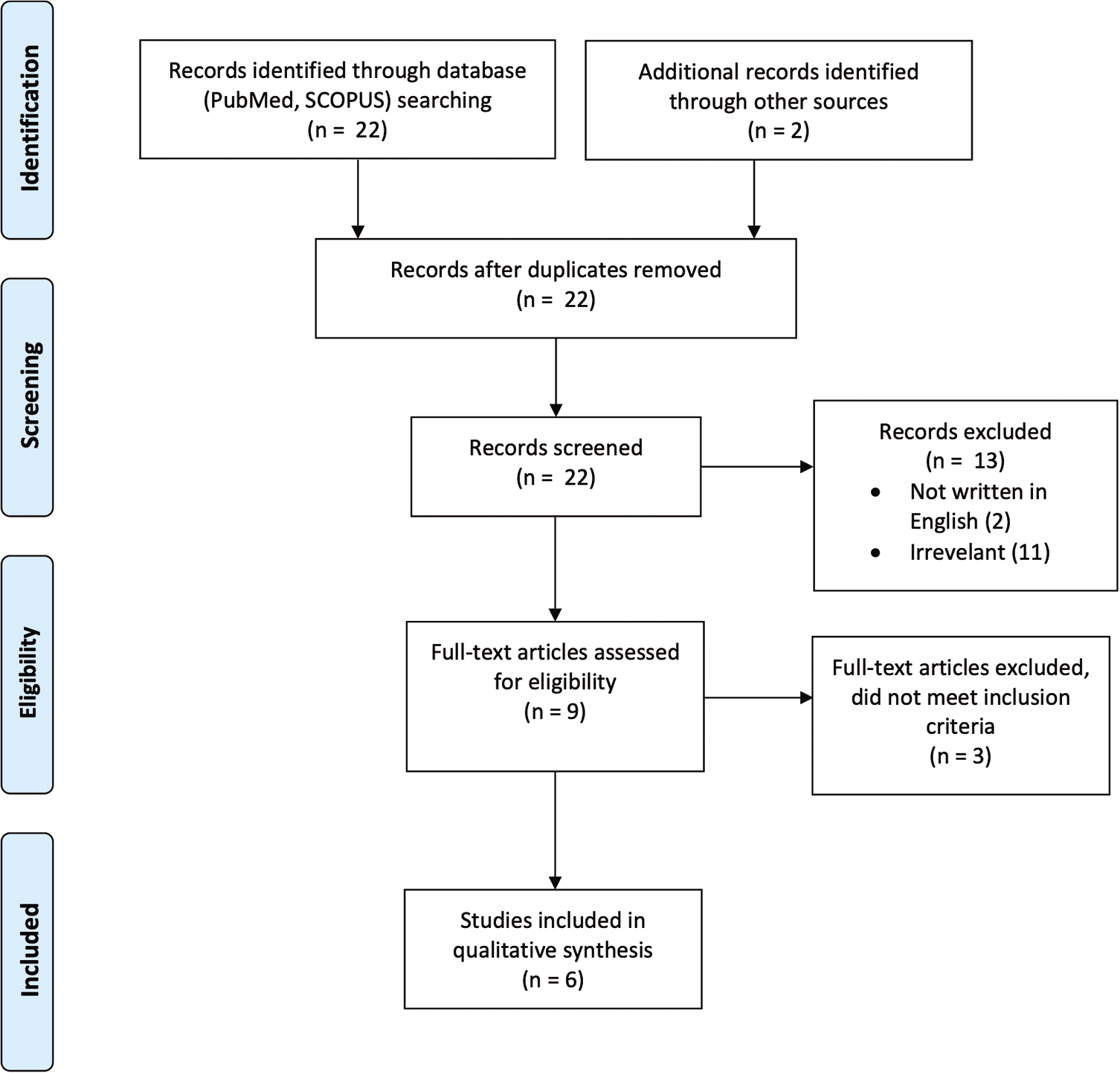

A systematic search of PubMed and SCOPUS databases was performed using the keywords “hemicraniectomy,” “malignant infarct” or “malignant edema,” and “COVID.” The reference lists of the assessed articles were also searched for relevant studies. All English-language case reports or case series about patients who were diagnosed with COVID-19 infection, developed cerebral infarct, and underwent DH were collected and analyzed. The data collected included demographics, clinical features, imaging results, laboratory parameters, outcomes, and complications.

A total of 22 records were identified through a database search. Of these, 13 articles were excluded after screening the titles and abstracts for relevance to the study. The full text of nine articles was assessed, of which three articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (e.g., no consent for hemicraniectomy). Six studies were included in the final qualitative analysis [

RESULTS

There were nine reported cases of patients with COVID-19 infection and large-vessel ischemic stroke who underwent DH, including the present case [

DISCUSSION

COVID-19 infection may primarily be a respiratory disease, but a meta-analysis showed that the incidence of acute ischemic stroke in COVID-19 patients ranges from 0.9 to 2.7%.[

It was difficult to determine if the ischemic stroke was incidental or was caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, but several theories have been proposed regarding the causative mechanism.

First, patients with COVID-19 infection were found to have elevated serum levels of circulating D-dimer, a marker of systemic hypercoagulability, and rendering patients prone to a cerebrovascular event.[

Another proposed mechanism was an exaggerated systemic inflammation or “cytokine storm” brought about by COVID-19 infection.[

A third proposed mechanism was the depletion of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) leading to endothelial dysfunction of the brain. ACE2 has been shown to enhance atherosclerotic plaque stability and has a cardiovascular protective effect.[

Moreover, the accompanying hypoxemia brought about by the infection leads to intracellular acidosis and increases anaerobic metabolism, worsening the cerebral edema, and eventually leading to cell damage and apoptosis.[

All nine patients in this series underwent DH; however, five did not survive and only four were alive at the time of writing, with one of them on palliative care. This translates into a mortality rate of 56%, which is higher than the mortality rates reported in the pre-COVID era. The mortality rate ranged from 8 to 31% in non-randomized prospective case series of patients who underwent DH for malignant hemispheric infarction,[

Furthermore, the cause of death for all five patients in the series was non neurologic, with respiratory failure being the most common cause. In comparison, non neurologic causes of death only comprise about 20–33%[

Indeed, the preliminary reports of the outcomes of DH for ischemic stroke in COVID-19 patients were dismal despite early intervention, making us wonder if the presence of COVID-19 infection should be factored into the decision to undergo neurosurgical intervention. Some authors have even suggested conservative management of COVID-19 related malignant infarcts because of the poor prognosis.[

Prospective studies with a larger sample size and more comprehensive collection of clinical and laboratory data are essential to establish a prediction model and prognostic effect. Furthermore, the prognostic variables that have been identified in the reported studies used mortality as end points. Other variables may also be relevant in the outcomes of patients, such as pulmonary function ratio, duration of mechanical ventilation, and need for sedation, and larger studies using multivariate analysis would be required.

Given the possible association between COVID-19 and stroke, healthcare workers have to be cognizant of the neurovascular complications that may occur during the course of COVID-19 illness. In the Philippines, patients with mild cases of COVID-19 are advised to quarantine at home or at quarantine facilities; thus, patients and their families must be advised regarding the potential risk for stroke and surveillance for neurologic manifestations so that they can seek medical intervention in a timely manner.

Stroke diagnosis and monitoring may also be challenging in patients with severe COVID-19 infection admitted in the ICU. The dyspnea, air hunger, and physical discomfort of being intubated may require continuous deep sedation and paralysis for these patients. Moreover, deep sedation is recommended for intubated COVID-19 patients because it permits proper lung ventilation in patients with respiratory distress syndrome.[

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread, our understanding on how to approach and treat patients is continuously evolving. Even if COVID-19 is primarily a pulmonary disease, the cases in this series demonstrate that affected patients can develop acute infarcts despite a younger age, and the outcome is generally poor even after neurosurgical intervention.

CONCLUSION

DH for cerebral infarction associated with COVID-19 infection has been reported in nine cases. The operation was performed between the 1st and 3rd days post-ictus (mean 1.8 days), but despite early surgical intervention, the outcomes were generally poor.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Al Saiegh F, Ghosh R, Leibold A, Avery MB, Schmidt RF, Theofanis T. Status of SARS-CoV-2 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with COVID-19 and stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020. 91: 846-8

2. Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E. Surviving sepsis campaign: Guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med. 2020. 46: 854-87

3. Dasenbrock HH, Robertson FC, Vaitkevicius H, Aziz-Sultan MA, Guttieres D, Dunn IF. Timing of decompressive hemicraniectomy for stroke: A nationwide inpatient sample analysis. Stroke. 2017. 48: 704-11

4. De R, Maity A, Bhattacharya C, Das S, Krishnan P. Licking the lungs, biting the brain: Malignant MCA infarct in a patient with COVID 19 infection. Br J Neurosurg. 2020. p. 1-2

5. Dhama K, Khan S, Tiwari R, Sircar S, Bhat S, Malik YS. Coronavirus disease 2019-COVID-19. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020. 33: e00028

6. Dostovic Z, Dostovic E, Smajlovic D, Avdic O. Brain edema after ischaemic stroke. Med Arch. 2016. 70: 339-41

7. Dougu N, Takashima S, Sasahara E, Taguchi Y, Toyoda S, Hirai T. Differential diagnosis of cerebral infarction using an algorithm combining atrial fibrillation and D-dimer level. Eur J Neurol. 2008. 15: 295-300

8. Fandino J, Keller E, Barth A, Landolt H, Yonekawa Y, Seiler RW. Decompressive craniotomy after middle cerebral artery infarction. Retrospective analysis of patients treated in three centres in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2004. 134: 423-9

9. González-Pinto T, Luna-Rodríguez A, Moreno-Estébanez A, Agirre-Beitia G, Rodríguez-Antigüedad A, Ruiz-Lopez M. Emergency room neurology in times of COVID-19: Malignant ischaemic stroke and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Neurol. 2020. 27: e35-6

10. Hess DC, Eldahshan W, Rutkowski E. COVID-19-related stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2020. 11: 322-5

11. Jüttler E, Unterberg A, Woitzik J, Bösel J, Amiri H, Sakowitz OW. Hemicraniectomy in older patients with extensive middle-cerebral-artery stroke. N Engl J Med. 2014. 370: 1091-100

12. Kamran S, Salam A, Akhtar N, Alboudi A, Ahmad A, Khan R. Predictors of in-hospital mortality after decompressive hemicraniectomy for malignant ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017. 26: 1941-7

13. Kananeh MF, Thomas T, Sharma K, Herpich F, Urtecho J, Athar MK. Arterial and venous strokes in the setting of COVID-19. J Clin Neurosci. 2020. 79: 60-6

14. Kilincer C, Asil T, Utku U, Hamamcioglu MK, Turgut N, Hicdonmez T. Factors affecting the outcome of decompressive craniectomy for large hemispheric infarctions: A prospective cohort study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005. 147: 587-94

15. Kwak Y, Kim BJ, Park J. Maximum decompressive hemicraniectomy for patients with malignant hemispheric infarction. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. 2019. 21: 138-43

16. Liang JW, Reynolds AS, Reilly K, Lay C, Kellner CP, Shigematsu T. COVID-19 and decompressive hemicraniectomy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2020. 51: e215-8

17. Malm J, Bergenheim AT, Enblad P, Hårdemark HG, Koskinen LO, Naredi S. The Swedish malignant middle cerebral artery infarction study: Long-term results from a prospective study of hemicraniectomy combined with standardized neurointensive care. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006. 113: 25-30

18. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020. 77: 683-90

19. Markus HS, Brainin M. COVID-19 and stroke-a global World Stroke Organization perspective. Int J Stroke. 2020. 15: 361-4

20. Merkler AE, Parikh NS, Mir S, Gupta A, Kamel H, Lin E. Risk of Ischemic stroke in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vs patients with influenza. JAMA Neurol. 2020. 77: 1-7

21. Mohammad LM, Botros JA, Chohan MO. Necessity of brain imaging in COVID-19 infected patients presenting with acute neurological deficits. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2020. 22: 100883

22. Oh JS, Bae HG, Oh HG, Yoon SM, Doh JW, Lee KS. The changing trends in age of first-ever or recurrent stroke in a rapidly developing urban area during 19 years. J Neurol Neurosci. 2017. 8: 206

23. Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, Kellner CP, Shoirah H, Singh IP. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of COVID-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020. 382: e60

24. Patel SD, Kollar R, Troy P, Song X, Khaled M, Parra A. Malignant cerebral ischemia in a COVID-19 infected patient: Case review and histopathological findings. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020. 29: 105231

25. Pillai A, Menon SK, Kumar S, Rajeev K, Kumar A, Panikar D. Decompressive hemicraniectomy in malignant middle cerebral artery infarction: An analysis of long-term outcome and factors in patient selection. J Neurosurg. 2007. 106: 59-65

26. Pisano TJ, Hakkinen I, Rybinnik I. Large vessel occlusion secondary to COVID-19 hypercoagulability in a young patient: A case report and literature review. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020. 29: 105307

27. Qureshi AI, Ishfaq MF, Rahman HA, Thomas AP. Hemicraniectomy versus conservative treatment in large hemispheric ischemic stroke patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016. 25: 2209-14

28. Roy D, Hollingworth M, Kumaria A. A case of malignant cerebral infarction associated with COVID-19 infection. Br J Neurosurg. 2020. p. 1-4

29. Tan YK, Goh C, Leow AS, Tambyah PA, Ang A, Yap ES. COVID-19 and ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-summary of the literature. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020. 50: 587-95

30. Tardif JC. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and atherosclerotic plaque: A key role in the cardiovascular protection of patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2009. 11: E9-16

31. Wu Y, Xu X, Chen Z, Duan J, Hashimoto K, Yang L. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Immun. 2020. 87: 18-22

32. Zi WJ, Shuai J. Plasma D-dimer levels are associated with stroke subtypes and infarction volume in patients with acute ischemic stroke. PLoS One. 2014. 9: e86465