- Department of Neurosurgery, Hitachi General Hospital, Hitachi, Ibaraki, Japan,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan

Correspondence Address:

Takao Koiso, Department of Neurosurgery, Hitachi General Hospital, Hitachi, Ibaraki, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1273_2021

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Takao Koiso1, Yoji Komatsu1, Yuji Matsumaru2, Eiichi Ishikawa2. Difficulty of diagnosing a mucor-induced aneurysm arising in segment P4 of the posterior cerebral artery – A case report. 31-Mar-2022;13:111

How to cite this URL: Takao Koiso1, Yoji Komatsu1, Yuji Matsumaru2, Eiichi Ishikawa2. Difficulty of diagnosing a mucor-induced aneurysm arising in segment P4 of the posterior cerebral artery – A case report. 31-Mar-2022;13:111. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11506/

Abstract

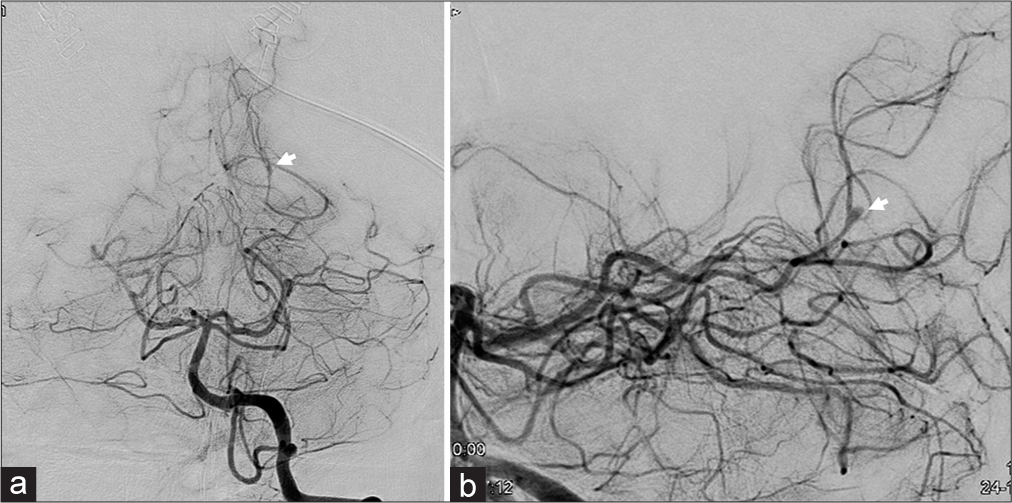

Background: Identification of causative pathogen for fungal aneurysm is frequently difficult. We reported the case of a fungal aneurysm caused by Mucor arising in segment P4 of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) detected only by histopathological examination.

Case Description: A 50-year-old female complained of nausea and vomiting. Computed tomography showed an intracranial hemorrhage in the left occipital lobe and acute hydrocephalus due to intraventricular hemorrhaging. Digital subtraction angiography performed after external drainage showed a cerebral aneurysm in segment P4 of the left PCA. Surgical excision of the aneurysm and end-to-end anastomosis of the PCA were performed. A histopathological examination revealed that the aneurysm had been caused by a Mucor infection.

Conclusion: In fungal aneurysm cases, especially those involving Mucor infections, it is difficult to identify the causative fungal infection based on cultures, imaging, and serological tests. Therefore, surgical excision and histopathological diagnosis are important for diagnosing such cases if possible.

Keywords: Fungal aneurysm, Histopathological examination, P4 segment

INTRODUCTION

Infectious cerebral aneurysms include both bacterial and fungal aneurysms. Typically, bacterial aneurysms exhibit a distal location.[

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old female presented with nausea and vomiting. She had a history of ulcerative colitis and had used steroids for over 30 years. She also had undergone aortic root surgery and mechanical valve insertion for an aneurysm of the ascending aorta at the age of 48, and hence, was taking a Vitamin K antagonist. A clinical examination showed an impairment of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS] score: E3V4M6). Her systolic blood pressure had increased to >200 mmHg. Her body temperature was normal.

Laboratory studies showed a slightly elevated white blood cell (WBC) count and anemia. Her WBC was 11300/μL (normal, 3500–9000) and her hemoglobin level was 11.1 g/dL (normal, 11.5–16.6). In addition, her C-reactive protein level was 0.17 mg/dL (normal, <0.3). In coagulation tests, it was found that the patient’s prothrombin time-international normalized ratio was elevated to 2.47, and her D-dimer level had also increased to 5.7 μg/mL (normal, <1.0). Two sets of blood cultures and a urinary culture were negative.

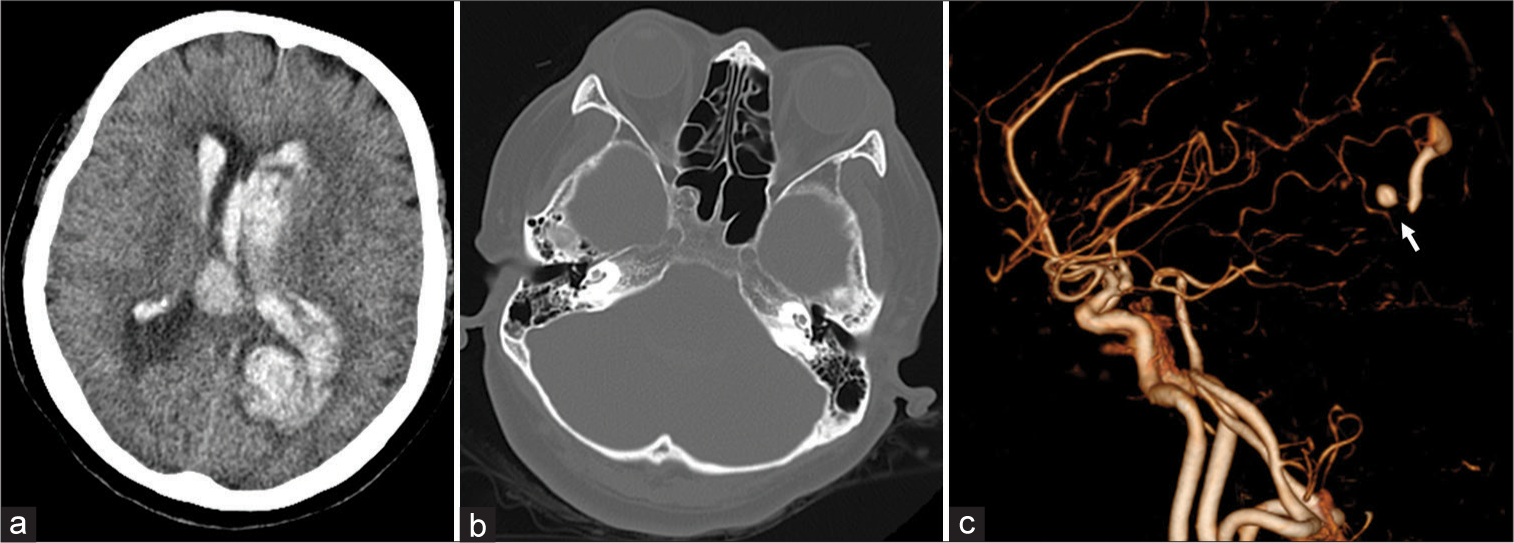

Brain computed tomography (CT) revealed a subcortical hemorrhage in the left occipital lobe and acute hydrocephalus due to intraventricular hemorrhaging [

Figure 1:

Computed tomography (CT) (a and b) and CT angiography (c) scans performed on admission (a) Brain window image showing an intracerebral hemorrhage in the left occipital lobe and an intraventricular hemorrhage (b) Bone window image showing no bone destruction or fluid storage in the paranasal sinus (c) CT angiography showed a cerebral aneurysm (arrow) in the distal left posterior cerebral artery.

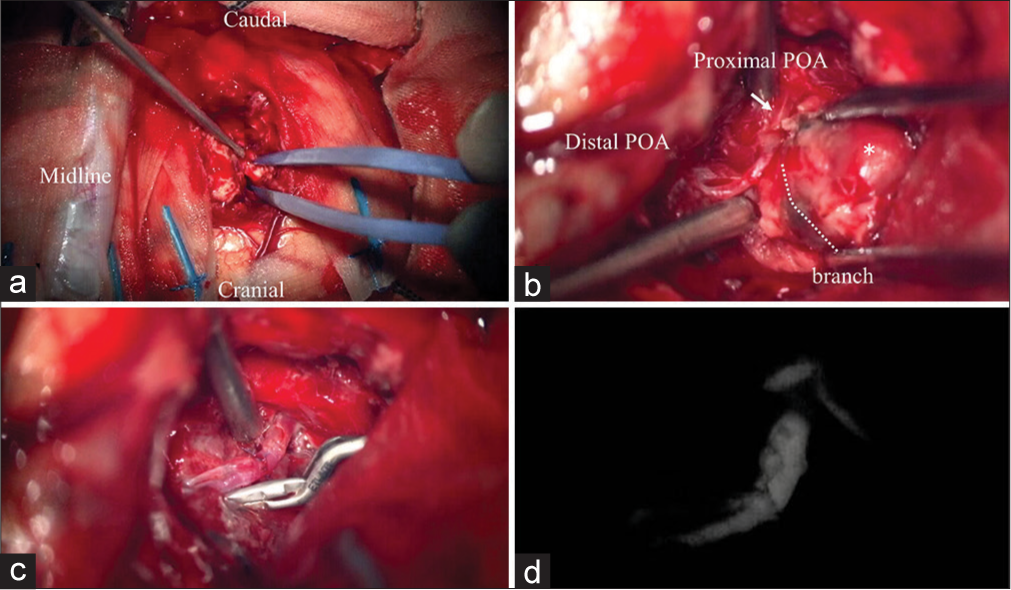

The patient’s head was fixed in the prone position using a Sugita frame and the left occipital craniotomy was carried out. The location of the hematoma was confirmed by ultrasonography. A corticotomy was made in the superior occipital gyrus and the hematoma was approached [

Figure 3:

Intraoperative photographs. (a) Left occipital craniotomy and corticotomy in the superior occipital gyrus were performed. (b) The proximal (arrow) and distal (arrowhead) posterior occipital artery were exposed. Intra-aneurysmal thrombosis was found (asterisk). (c) The aneurysm was removed, and end-to-end anastomosis of the normal sections of the proximal and distal POA was performed. (d) Indocyanine green video angiography confirmed the patency of the bypass.

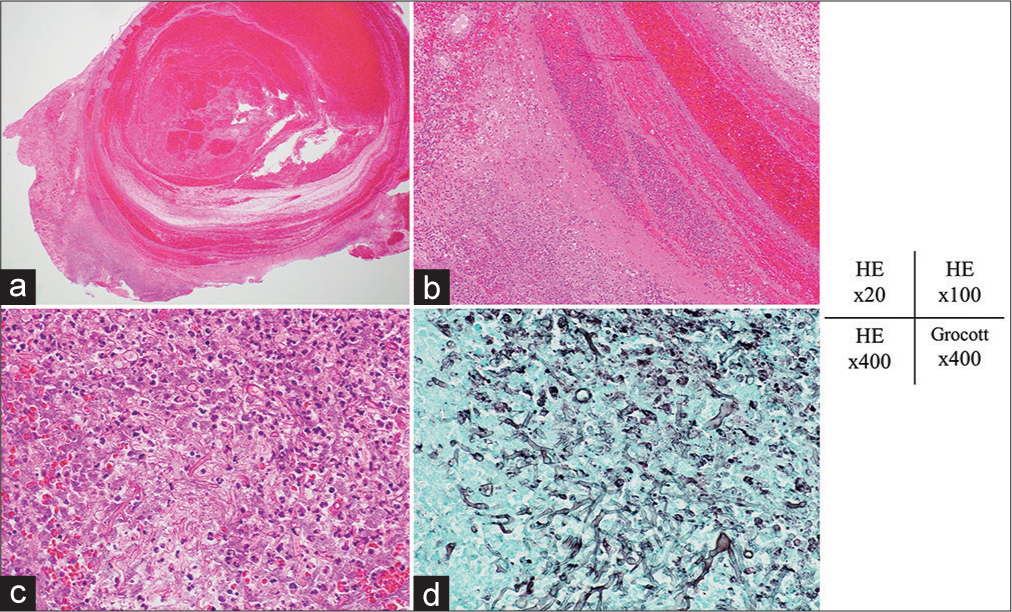

Figure 4:

Hematoxylin and eosin staining. (a and b) Photomicrographs showing that the elastic fibers had disappeared from the aneurysm wall and only fibrotic tissue was present. (c) Photomicrograph of the outside of the aneurysm showing the accumulation of neutrophils and lymphocytes, and coenocytic hyphae in the necrotic tissue. (d) Photomicrograph obtained after staining using Grocott’s method showing coenocytic hyphae, which varied in width and exhibited right-angled branching. These findings are characteristic of zygomycetes. Original magnification: (a) ×20, (b) ×100, (c) ×400, and (d) ×400.

Postoperative CT and magnetic resonance imaging only revealed a small hematoma in the left occipital lobe, but no cerebral infarction. As status epilepticus occurred on postoperative day (POD) 1, the propofol-induced general anesthesia was maintained, and anticonvulsant drugs were administered. The patient’s cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed a slightly elevated cell count (117/μL) and a normal glucose level (96 mg/dL) on POD 7. Tests for serum β-D-glucan and Aspergillus antigen were negative on POD 9. After a definitive diagnosis was made based on a histopathological examination on POD 10, we administered 600 mg/day voriconazole. The patient’s consciousness level gradually improved and she was extubated on POD 10. Heparinization was performed to prevent thromboembolic events from POD 18. The source of the infection was not found during transesophageal echocardiography performed on POD 21 or contrast-enhanced whole-body CT conducted on POD 22. Six blood cultures and a CSF culture obtained after surgery were all negative. The patient’s condition suddenly worsened after vomiting on POD 31 and she died on POD 32. An autopsy revealed pneumonia in the dorsal section of the right lung. Aspiration pneumonia might have been the cause of death. No systemic fungal infection was found.

DISCUSSION

This was a reported case of a fungal aneurysm arising in segment P4 of the PCA. Mucor was the cause of the fungal aneurysm. A histopathological examination was required to reach a diagnosis in this case.

In cases of fungal aneurysms, confirming a fungal infection using cultures, imaging, or serological tests is often difficult.[

In some cases of fungal aneurysms due to sinusitis, it is possible to determine the causative fungi through a histopathological examination of the sinus.[

Some infectious aneurysms have recently been treated using endovascular therapy.[

CONCLUSION

We described a case of a Mucor aneurysm arising in segment P4 of the PCA. In this case, making a definitive diagnosis is difficult without a pathological examination. If you cannot identify pathogen, surgical excision and pathological examination of the aneurysm should be considered.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Azar MM, Assi R, Patel N, Malinis MF. Fungal mycotic aneurysm of the internal carotid artery associated with sphenoid sinusitis in an immunocompromised patient: A case report and review of the literature. Mycopathologia. 2016. 181: 425-33

2. Barami K, Ko K. Ruptured mycotic aneurysm presenting as an intraparenchymal hemorrhage and nonadjacent acute subdural hematoma: Case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1994. 41: 290-93

3. Clare CE, Barrow DL. Infectious intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1992. 3: 551-66

4. Ducruet AF, Hickman ZL, Zacharia BE, Narula R, Grobelny BT, Gorski J. Intracranial infectious aneurysms: a comprehensive review. Neurosurg Rev. 2010. 33: 37-46

5. Fujiki S, Shime N, Hirose Y, Kosaka T, Fujita N. Role of the β-Dglucan assay in the diagnosis and treatment of fungemia and deep-seated mycoses. J Jpn Soc Intensive Care Med. 2010. 17: 33-8

6. Hirai S, Ogawa Y, Kinoshita K, Takai H, Matsushita N, Hara K. A case of multiple cerebral aneurysms associated with Aspergillus infection and recurrence of subarachnoid hemorrhage determined at autopsy. Jpn J Stroke. 2018. 40: 163-8

7. Hot A, Mazighi M, Lecuit M, Poirée S, Viard JP, Loulergue P. Fungal internal carotid artery aneurysms: Successful embolization of an Aspergillus associated case and review. Clin Infect Dis. 2007. 45: e156-61

8. Jao SY, Weng HH, Wong HF, Wang WH, Tsai YH. Successful endovascular treatment of intractable epistaxis due to ruptured internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to invasive fungal sinusitis. Head Neck. 2011. 33: 437-40

9. Jiang C, Lu H, Guo Y, Zhu L, Luo T, Ziai W. Blood culture-negative but clinically diagnosed infective endocarditis complicated by intracranial mycotic aneurysm, brain abscess, and posterior tibial artery pseudoaneurysm. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2018. 2018: 1236502

10. Kannoth S, Iyer R, Thomas SV, Furtado SV, Rajesh BJ, Kesavadas C. Intracranial infectious aneurysm: Presentation, management and outcome. J Neurol Sci. 2007. 256: 3-9

11. Katragkou A, Walsh TJ, Roilides E. Why is mucormycosis more difficult to cure than more common mycoses?. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014. 20: 74-81

12. Komatsu Y, Narushima K, Kobayashi E, Tomono Y, Nose T. Aspergillus mycotic aneurysm--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1991. 31: 346-50

13. Negoro E, Morinaga K, Taga M, Kaizaki Y, Kawai Y. Mycotic aneurysm due to Aspergillus sinusitis. Int J Hematol. 2013. 98: 4-5

14. Okada Y, Shima T, Nishida M, Yamane K, Yoshida A. Subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by Aspergillus aneurysm as a complication of transcranial biopsy of an orbital apex lesion--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1998. 38: 432-7

15. Phuong LK, Link M, Wijdicks E. Management of intracranial infectious aneurysms: A series of 16 cases. Neurosurgery. 2002. 51: 1145-51

16. Sundaram C, Goel D, Uppin SG, Seethajayalakshmi S, Borgohain R. Intracranial mycotic aneurysm due to Aspergillus species. J Clin Neurosci. 2007. 14: 882-6

17. Thajeb P, Thajeb T, Dai D. Fatal strokes in patients with rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis and associated vasculopathy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004. 36: 643-8

18. van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, Beute GN. Endovascular treatment of posterior cerebral artery aneurysms. Am J Neuroradiol. 2006. 27: 300-5

19. Varghese B, Ting K, Lopez-Mattei J, Iliescu C, Kim J, Kim P. Aspergillus endocarditis of the mitral valve with ventricular myocardial invasion, cerebral vasculitis, and intracranial mycotic aneurysm formation in a patient with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2018. 21: 49-51

20. Venkatesh SK, Phadke RV, Kalode RR, Kumar S, Jain VK. Intracranial infective aneurysms presenting with haemorrhage: An analysis of angiographic findings, management and outcome. Clin Radiol. 2000. 55: 946-53

21. Wang H, Rammos S, Fraser K, Elwood P. Successful endovascular treatment of a ruptured mycotic intracavernous carotid artery aneurysm in an AIDS patient. Neurocrit Care. 2007. 7: 156-9

22. Yamaguchi J, Kawabata T, Motomura A, Hatano N, Seki Y. Fungal internal carotid artery aneurysm treated by trapping and high-flow bypass: A case report and literature review. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2016. 56: 89-94

23. Ziaee A, Zia M, Bayat M, Hashemi J. Molecular identification of mucor and Lichtheimia species in pure cultures of Zygomycetes. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2016. 9: e35237