- Departments of Neurosurgery, Rabin Medical Center, Petha Tiqva, Israel.

- Departments of Pathology, Rabin Medical Center, Petha Tiqva, Israel.

Correspondence Address:

Yosef Laviv

Departments of Neurosurgery, Rabin Medical Center, Petha Tiqva, Israel.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_171_2020

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Idan Levitan, Suzana Fichman, Yosef Laviv. Fulminant presentation of a SMARCB1-deficient, anterior cranial fossa tumor in adult. Surg Neurol Int 18-Jul-2020;11:195

How to cite this URL: Idan Levitan, Suzana Fichman, Yosef Laviv. Fulminant presentation of a SMARCB1-deficient, anterior cranial fossa tumor in adult. Surg Neurol Int 18-Jul-2020;11:195. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10139/

Abstract

Background: Malignant atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT) usually develops in children. ATRTs are rare in adults, with only one case in the literature describing involvement of the anterior skull base. These primary intracranial tumors are characterized molecularly as SMARCB1 (INI1) deficient. Different types of such SMARCB1-deficient tumors exist in adulthood, usually in the form of extracranial tumors. Very few cases of such a new entity, named SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal carcinoma have been described with intracranial penetration and involvement of the anterior cranial fossa.

Case Description: A 36-year-old male presented with acute cognitive deterioration. Over few hours, he developed a fulminant herniation syndrome. Imaging showed a tumor in the anterior cranial fossa surrounded by massive brain edema. The tumor has destroyed the frontal bone with involvement of the nasal cavities and paranasal sinuses. The patient underwent emergent decompressive craniectomy and tumor debulking but could not be saved. Pathological analysis revealed a highly cellular tumor without rhabdoid cells but with areas of necrosis. Further immunohistochemical stains revealed that neoplastic cells were diffusely and strongly positive for epithelial membrane antigen and P63 and negative for SMARCB1 (i.e., loss of expression), confirming the diagnosis of sinonasal carcinoma.

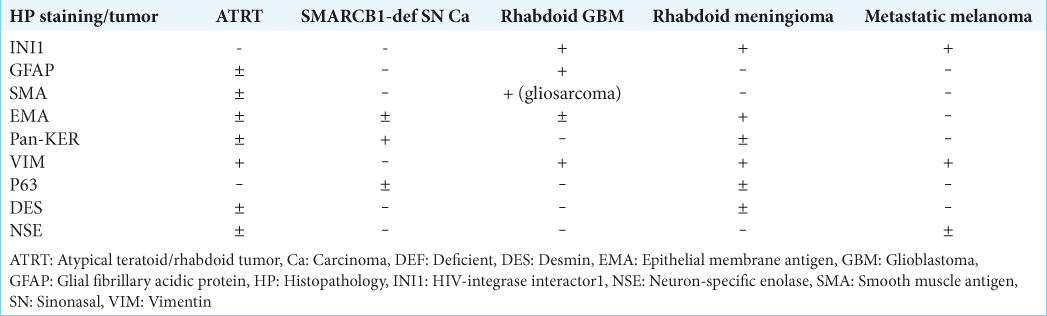

Conclusion: To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a fulminant presentation of a SMARCB1- deficient tumor in young adult, involving the anterior cranial fossa and the paranasal sinuses. The main differential diagnosis of aggressive, primary, intracranial SMARCB1-deficient tumors in adults includes ATRT, SMARCB1- deficient sinonasal carcinoma, rhabdoid meningioma, and rhabdoid glioblastoma. Atypical tumors involving the anterior skull base without a clear histopathological pattern should therefore be checked for SMARCB1 expression.

Keywords: Anterior cranial fossa, INI1, Rhabdoid, Sinonasal carcinoma, SMARCB1

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

A number of tumor suppressor genes are important in regulating transcription in eukaryotic neoplastic tissue. SMARCB1 is such a gene which has been named by acronyms for its function: switch/sucrose nonfermentable (SWI/SNF) related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily B, member 1. It is a tumor suppressor gene that encodes a core subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex positively regulating transcription of a particular set of genes involved in differentiation, tumorigenesis, invasion, and apoptosis.[

SMARCB1 is ubiquitously expressed in the nuclei of all nonneoplastic cells and can be readily identified using immunohistochemistry.[

The spectrum of non-ATRT, cranial SMARCB1-deficient tumors mostly includes other pediatric tumors, such as the benign cribriform neuroepithelial tumor and rare poorly differentiated chordomas.[

We present an extremely rare case in which a SMARCB1- deficient tumor, with both extracranial and intracranial components, presented with a fulminant clinical course of cognitive deterioration and subsequent loss of consciousness, resulting in death in a young adult. The differential diagnosis of primary, cranial, and SMARCB1-deficient tumors in adults is discussed.

CASE REPORT

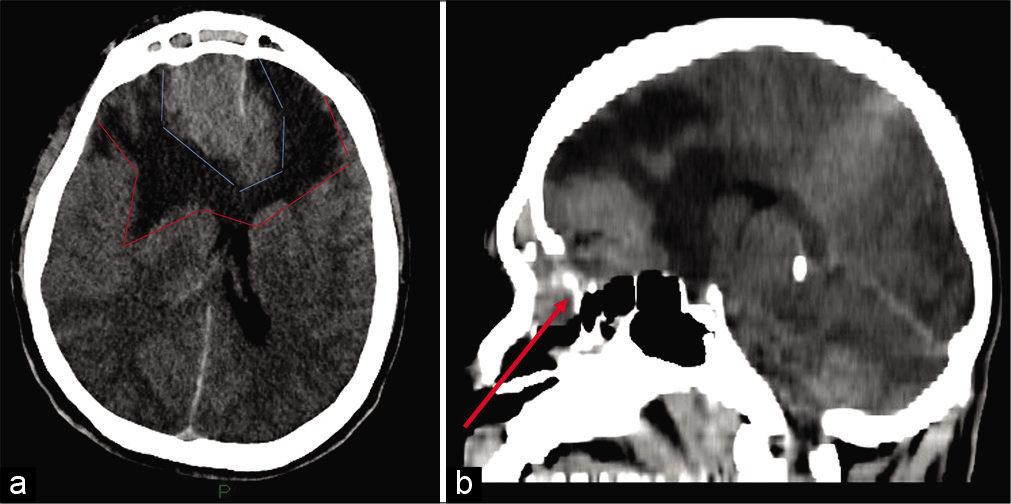

A 36-year-old otherwise healthy male presented to an outside hospital with blurred vision for few days and acute onset of aggressive behavior and agitation. While in the emergency department, he deteriorated rapidly to a Glasgow Coma Scale of 8 requiring intubation. A head computed tomography (CT) revealed a large, bifrontal extra-axial mass of the anterior skull base, measuring 52 mm × 37 mm. The lesion also involved the ethmoid cells and frontal sinuses as well as the right orbit. It was infiltrating the dura. Extended peritumoral brain edema with significant mass effect was also noted [

Figure 1:

(a) Noncontrast head CT (axial cut) at time of presentation, showing large bifrontal mass (light blue lines) surrounded by brain edema (red lines), causing significant mass effect. (b) Sagittal cut. The tumor has destroyed the frontal bone, extending into the paranasal sinuses (arrow) and intracranially, involving the anterior skull base.

At surgery, the tumor was found to be very vascular. On opening the dura, the brain was swollen and of firm consistency with no pulsations. A debulking operation was performed along with bifrontal decompressive craniectomy. An intracranial pressure (ICP) monitor was inserted to the parenchyma. The ICP levels were <25 mmHg on average during the postoperative course, the patient was in Glasgow Come Scale 3, with no brain stem reflexes. Postoperative head CT demonstrated persistent, bilateral, massive edema, the patient’s condition remained critical and he passed away 1 week later.

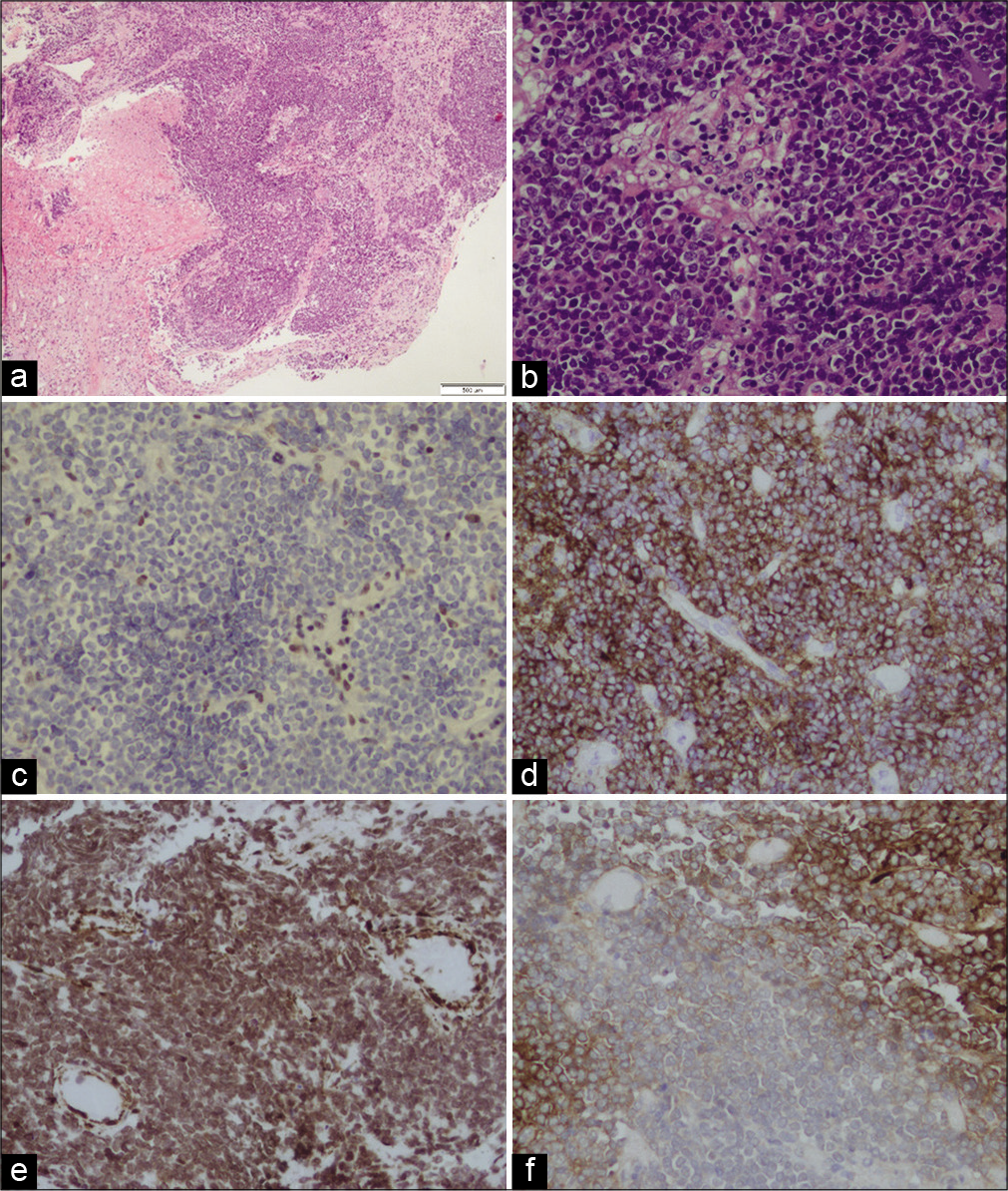

Histological examination for hematoxylin and eosin stain showed a tumor comprised small to medium size cells, some of them with clear cytoplasm. Rhabdoid cells were not noted. The tumor shows areas of necrosis and high levels of mitotic and apoptotic activity [

Figure 2:

(a) Histological examination for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain showing a tumor comprised small to medium size cells, some of them with clear cytoplasm. Rhabdoid cells were not noted. The tumor shows areas of necrosis. (b) H&E, ×20. (c) The stain for INI1 was negative (loss of expression). Immunohistochemical stains were diffusely and strong positive for EMA (d) and partially positive for SMA (e) and GFAP (f).

DISCUSSION

ATRTs are primary rhabdoid tumors of the central nervous system (CNS). They are rare malignant brain tumors usually diagnosed in children younger than 3 years old[

Immunohistochemical study using antibody against the INI1 gene product or fluorescence in situ hybridization to identify loss of the INI1 locus is the current routine workup for diagnostic confirmation of ATRT.[

ATRTs can exhibit epithelial, primitive neuroepithelial, and mesenchymal differentiation. Histologically, the mesenchymal component of ATRTs is characterized by cells with discrete borders and a rhabdoid morphology, that is, abundant cytoplasm with eosinophilic paranuclear inclusions of intermediate filaments. These filaments are identified as vimentin by immunohistochemistry.[

In adult patients, it is very difficult to render a diagnosis of ATRT for CNS malignant tumors, even when a predominant rhabdoid cell component is present, because there are more common malignant tumors (primary and metastatic) that show rhabdoid features, such as rhabdoid glioblastoma, rhabdoid meningioma, metastatic melanoma, and metastatic carcinomas with rhabdoid features, all occurring in this age group.[

Tumors resembling ATRT, staining with GFAP, as well as vimentin, SMA, and EMA have been suggested to represent rhabdoid glioblastoma. Rhabdoid glioblastoma (GBM) is an aggressive variant of glioblastoma, which mainly affects young subjects. It can involve the leptomeninges,[

Bone involvement of the skull in ATRT patients is extremely rare, especially in adults. Although hematogenous tumor spread to the skeleton is a rare, it has been a well-known finding in medulloblastomas, though few reports on destruction or invasion of the adjacent skull in medulloblastomas or other CNS primitive neuroectodermal tumors exist.[

In 2016, the first and only report of adult ATRT involving the nasal cavities and anterior skull base was published.[

Sinonasal tract malignancies are uncommon, representing no more than 5% of all head-and-neck cancers.[

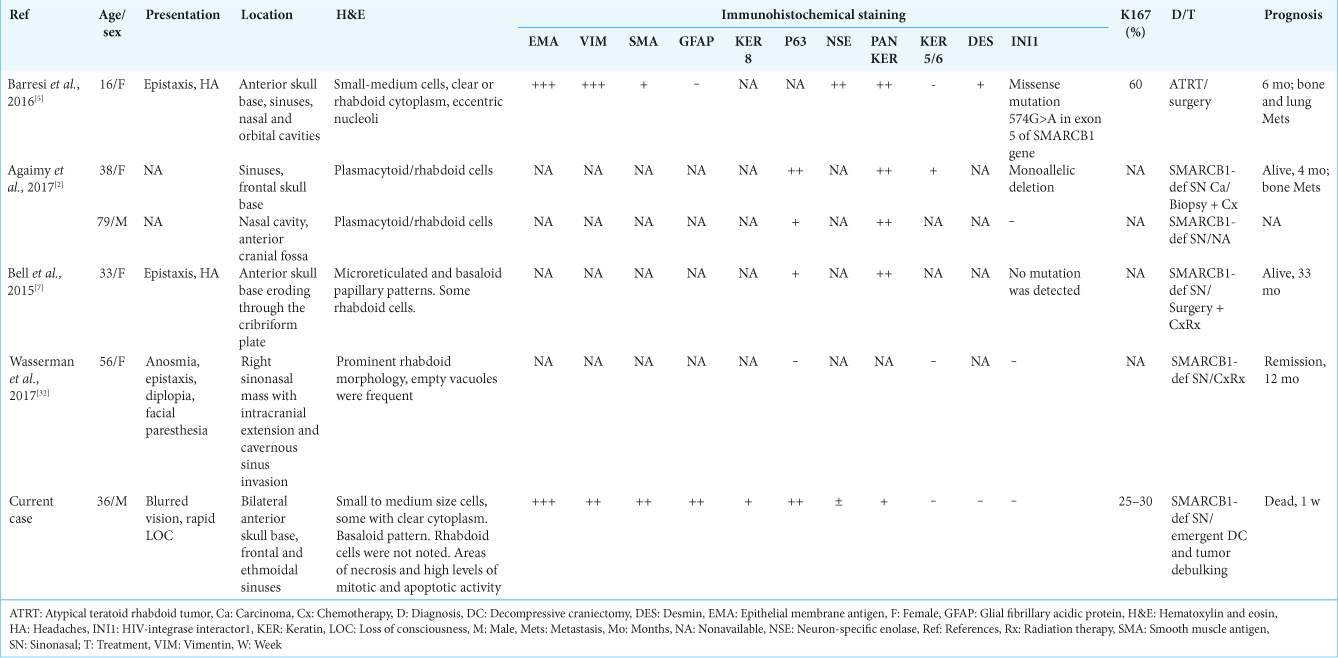

In a literature’s review of other cases of SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal carcinoma, three more cases involving the anterior skull base with intracranial penetration were reported[

A subset of SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal carcinomas, particularly the basaloid form, demonstrates diffuse p63 immunoreactivity that may result in a misdiagnosis of nonkeratinizing/basaloid SCC or NUT midline carcinoma.[

It seems that the diagnosis of SMARCB1-deficient tumors is more frequently made as more and more subtypes are being discovered. In 2017, Dadone et al. described two unique cases of meningeal-related tumors.[

Based on shared phenotype and genotype features, the authors suggested that these cases are part of an emerging group of primary meningeal SMARCB1-deficient tumors, not described to date. Our case was infiltrating the dura, but showed much more aggressive behavior as compared to the cases described by Dadone et al. Unfortunately, due to insufficient material saved for pathology and the absence of fresh frozen samples, we could not perform molecular analysis of the tumor which might have helped reaching more definite diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

Given the radiological, morphological, and pathological data, we believe that the current case represents an extremely aggressive behavior of a SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal carcinoma, possibly of the basaloid subtype. Although it is difficult to explain the positive staining for GFAP, all other data support the diagnosis of sinonasal carcinoma over ATRT. Due to the extreme rarity of reported cases, we cannot suggest that this case represents an aggressive variant of other more recently described primary meningeal SMARCB1-deficient tumors. The fulminant presentation can be explained, perhaps, by infiltration and occlusion of the superior sagittal sinus as well as by mass effect and rapid compression and obstruction of venous outflow, resulting in massive bifrontal brain edema. To the best of our knowledge, this aggressive presentation of a SMARCB1-deficient anterior cranial fossa tumor has never been described before.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not obtained as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Agaimy A. The expanding family of SMARCB1(INI1)-deficient neoplasia: Implications of phenotypic, biological, and molecular heterogeneity. Adv Anat Pathol. 2014. 21: 394-410

2. Agaimy A, Hartmann A, Antonescu CR, Chiosea SI, El-Mofty SK, Geddert H. SMARCB1 (INI-1)-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: A series of 39 cases expanding the morphologic and clinicopathologic spectrum of a recently described entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017. 41: 458-71

3. Agaimy A, Koch M, Lell M, Semrau S, Dudek W, Wachter DL. SMARCB1(INI1)-deficient sinonasal basaloid carcinoma: A novel member of the expanding family of SMARCB1-deficient neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014. 38: 1274-81

4. Babu R, Hatef J, McLendon RE, Cummings TJ, Sampson JH, Friedman AH. Clinicopathological characteristics and treatment of rhabdoid glioblastoma. J Neurosurg. 2013. 119: 412-9

5. Barresi V, Branca G, Raso A, Mascelli S, Caffo M, Tuccari G. Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor involving the nasal cavities and anterior skull base. Neuropathology. 2016. 36: 283-9

6. Barresi V, Lionti S, Raso A, Esposito F, Cannavo S, Angileri FF. Pituitary atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor in a patient with prolactinoma: A unique description. Neuropathology. 2017. 6: 12440-

7. Bell D, Hanna EY, Agaimy A, Weissferdt A. Reappraisal of sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: SMARCB1 (INI1)-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: A single-institution experience. Virchows Arch. 2015. 467: 649-56

8. Bishop JA, Antonescu CR, Westra WH. SMARCB1 (INI-1)-deficient carcinomas of the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014. 38: 1282-9

9. Bodi I, Giamouriadis A, Sibtain N, Laxton R, King A, Vergani F. Primary intracerebral INI1-deficient rhabdoid tumor with CD34 immunopositivity in a young adult. Surg Neurol Int. 2018. 9: 45-

10. Byeon SJ, Cho HJ, Baek HW, Park CK, Choi SH, Kim SH. Rhabdoid glioblastoma is distinguishable from classical glioblastoma by cytogenetics and molecular genetics. Hum Pathol. 2014. 45: 611-20

11. Dadone B, Fontaine D, Mondot L, Cristofari G, Jouvet A, Godfraind C. Meningeal SWI/SNF related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily B member 1 (SMARCB1)-deficient tumours: An emerging group of meningeal tumours. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2017. 43: 433-49

12. Dardis C, Yeo J, Milton K, Ashby LS, Smith KA, Mehta S. Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor: Two case reports and an analysis of adult cases with implications for pathophysiology and treatment. Front Neurol. 2017. 8: 247-

13. Haerle SK, Gullane PJ, Witterick IJ, Zweifel C, Gentili F. Sinonasal carcinomas: Epidemiology, pathology, and management. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2013. 24: 39-49

14. Han L, Qiu Y, Xie C, Zhang J, Lv X, Xiong W. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors in adult patients: CT and MR imaging features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011. 32: 103-8

15. Hollmann TJ, Hornick JL. INI1-deficient tumors: Diagnostic features and molecular genetics. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011. 35: e47-63

16. Horiguchi H, Nakata S, Nobusawa S, Uyama S, Miyamoto T, Ueta H. Adult-onset atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor featuring long spindle cells with nuclear palisading and perivascular pseudorosettes. Neuropathology. 2017. 37: 52-7

17. Judkins AR, Eberhart EC, Wesseling P, Louis DN, Ohgaki OH, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK.editors. Atypical teratoid/ rhabdoid tumour. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System Revised. Lyon: IARC Press; 2016. p. 209-12

18. Kanoto M, Toyoguchi Y, Hosoya T, Kuchiki M, Sugai Y. Radiological image features of the atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor in adults: A systematic review. Clin Neuroradiol. 2015. 25: 55-60

19. Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Alassiri AH, Birks DK, Newell KL, Moore W, Lillehei KO. Epithelioid versus rhabdoid glioblastomas are distinguished by monosomy 22 and immunohistochemical expression of INI-1 but not claudin 6. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010. 34: 341-54

20. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016. 131: 803-20

21. Makuria AT, Rushing EJ, McGrail KM, Hartmann DP, Azumi N, Ozdemirli M. Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT) in adults: Review of four cases. J Neurooncol. 2008. 88: 321-30

22. Medjkane S, Novikov E, Versteege I, Delattre O. The tumor suppressor hSNF5/INI1 modulates cell growth and actin cytoskeleton organization. Cancer Res. 2004. 64: 3406-13

23. Nakata S, Nobusawa S, Hirose T, Ito S, Inoshita N, Ichi S. Sellar atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT): A clinicopathologically and genetically distinct variant of AT/RT. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017. 41: 932-40

24. Nishikawa A, Ogiwara T, Nagm A, Sano K, Okada M, Chiba A. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor of the sellar region in adult women: Is it a sex-related disease?. J Clin Neurosci. 2018. 49: 16-21

25. Raisanen J, Hatanpaa KJ, Mickey BE, White CL. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor: Cytology and differential diagnosis in adults. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004. 31: 60-3

26. Rorke LB, Packer RJ, Biegel JA. Central nervous system atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors of infancy and childhood: Definition of an entity. J Neurosurg. 1996. 85: 56-65

27. Shitara S, Akiyama Y. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor in sellar turcica in an adult: A case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2014. 5: 2152-7806

28. Takei H, Adesina AM, Mehta V, Powell SZ, Langford LA. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor of the pineal region in an adult. J Neurosurg. 2010. 113: 374-9

29. Versteege I, Sevenet N, Lange J, Rousseau-Merck MF, Ambros P, Handgretinger R. Truncating mutations of hSNF5/INI1 in aggressive paediatric cancer. Nature. 1998. 394: 203-6

30. Wang X, Liu X, Lin Z, Chen Y, Wang P, Zhang S. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT) arising from the acoustic nerve in a young adult: A case report and a review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015. 94: e439-

31. Warmuth-Metz M, Bison B, Gerber NU, Pietsch T, Hasselblatt M, Fruhwald MC. Bone involvement in atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors of the CNS. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013. 34: 2039-42

32. Wasserman JK, Dickson BC, Perez-Ordonez B, de Almeida JR, Irish JC, Weinreb I. INI1 (SMARCB1)-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: A clinicopathologic report of 2 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2017. 11: 256-61

33. Wilson BG, Roberts CW. SWI/SNF nucleosome remodellers and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011. 11: 481-92

34. Wu WW, Bi WL, Kang YJ, Ramkissoon SH, Prasad S, Shih HA. Adult atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors. World Neurosurg. 2016. 85: 197-204