- Division of Neurological Surgery, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ, U.S.A.

- Division of Neurological Surgery, National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Manuel Velasco Suarez, Mexico City, Mexico

- Division of Neurological Surgery, Hospital Medica Tec100, Queretaro, Mexico

Correspondence Address:

Rogelio Revuelta-Gutierrez

Division of Neurological Surgery, National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Manuel Velasco Suarez, Mexico City, Mexico

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.157443

Copyright: © 2015 Soriano-Baron H. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.How to cite this article: Soriano-Baron H, Vales-Hidalgo O, Arvizu-Saldana E, Moreno-Jimenez S, Revuelta-Gutierrez R. Hemifacial spasm: 20-year surgical experience, lesson learned. Surg Neurol Int 20-May-2015;6:83

How to cite this URL: Soriano-Baron H, Vales-Hidalgo O, Arvizu-Saldana E, Moreno-Jimenez S, Revuelta-Gutierrez R. Hemifacial spasm: 20-year surgical experience, lesson learned. Surg Neurol Int 20-May-2015;6:83. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/hemifacial-spasm-20%e2%80%91year-surgical-experience-lesson-learned-2/

Abstract

Background:Hemifacial spasm is characterized by unilateral, paroxysmal, and involuntary contractions. It is more common in women on the left side. Its evolution is progressive, and it rarely improves without treatment.

Methods:Microvascular decompressions (N = 226) were performed in 194 Hispanic patients (May 1992–May 2011). Outcomes were evaluated on a 4-point scale: Excellent (complete remission); good (1–2 spasms/day); bad (>2 spasms/day); and recurrence (relapse after initial excellent/good response).

Results:Most patients were female (n = 123); 71 were male. Mean (±SD) age was 49.4 (±11.7) years; age at onset, 43.9 (±11.9) years; time to surgery, 5.7 (±4.7) years. The left side was affected in 114 patients. Typical syndrome occurred in 177 (91.2%); atypical in 17 (8.8%). Findings were primarily vascular compression (n = 185 patients): Anterior inferior cerebellar artery (n = 147), posterior inferior cerebellar artery (n = 12), basilar artery (n = 10), superior cerebellar artery (n = 8), and 2 vessels (n = 8); 9 had no compression. Postsurgical results were primarily excellent (79.9% [n = 155]; good, 4.6% [n = 9]; bad, 15.5% [n = 30]), with recurrence in 21 (10.8%) at mean 51-month (range, 1–133 months) follow-up. Complications included transient hearing loss and facial palsy.

Conclusions:The anterior inferior cerebellar artery is involved in most cases of hemifacial spasm. Failure to improve postsurgically after 1 week warrants reoperation. Sex, side, and onset are unrelated to treatment response. Microvascular decompression is the preferred treatment. It is minimally invasive, nondestructive, and achieves the best long-term results, with minor morbidity. To our knowledge, this series is the largest to date on a Hispanic population.

Keywords: Cerebellopontine angle, facial nerve, facial tic, hemifacial spasm, microvascular decompression

INTRODUCTION

Hemifacial spasm (HFS) is an overactive facial nerve dysfunction syndrome with spontaneous and gradual onset characterized by unilateral, clonic, paroxysmal, and involuntary contractions of one or more facial muscles innervated by the same facial nerve.[

HFS occurs almost exclusively in adults.[

In general, HFS becomes worse over time.[

The pathogenesis of HFS is not fully understood.[

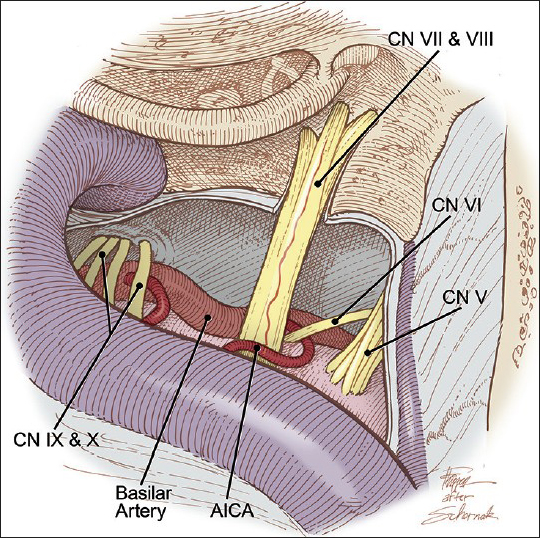

Figure 1

Vascular compression of the left facial nerve by the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) within the entry zone of the left facial nerve at the brainstem. CN indicates cranial nerve. Modified and used with permission from Zubay G, Porter RW, Spetzler RF: Transpetrosal approaches. Operative Techniques 4 (1):24-29, 2001

The diagnosis of HFS is clinical,[

Response is poor to medication therapy (e.g. carbamazepine, gabapentin).[

The aim of this study was to analyze the demographics, clinical manifestations, outcomes, and complications of patients who underwent microvascular decompression of the facial nerve for the treatment of HFS at the National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Manuel Velasco Suárez, Mexico City, Mexico, between May 1, 1992, and May 31, 2011.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 194 patients were diagnosed with HFS and surgically treated with microvascular decompression through a posterior fossa craniectomy by the senior author (R. R.-G.). A retrospective analysis was performed of the medical records of all patients to abstract sex, age, clinical history, evolution, previous treatment, preoperative imaging (computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging), surgical findings, complications, outcomes, and response to treatment. Postsurgical follow-up was performed with postoperative clinic visits. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery.

Postoperative results and follow-up findings were evaluated by the following criteria: (i) excellent: Complete remission of HFS (defined as 2 muscle spasms per week); (ii) good: 1 or 2 muscle spasms per day, with remarkable improvement from the preoperative state; (iii) bad: More than 2 muscle spasms per day, with slight improvement or status unchanged after surgery; and (iv) recurrence: Relapse of symptoms after initial excellent or good response.

Statistical analysis (counts, percentages, mean [SD], Fisher's exact test, and the Chi-square test) was conducted using SPSS statistical software (IBM Corp). Significance was defined as P = 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 226 microvascular decompressions were performed (194 first surgeries; 32 reinterventions) in 194 patients with HFS during the period of analysis.

Demographic findings

In this series of 194 patients, most were women (n = 123 [63.4%]); 71 were men (36.6%). The left side was affected in 114 patients (58.8%), the right side in 80 (41.2%). Patients ranged in age from 19 to 76 years (mean [±SD], 49.4 [±11.7] years). The mean (±SD [range]) age of onset was 43.9 years (±11.9 [range, 3–70] years), and the time to surgery was 5.7 years (±4.7 [1–30] years).

There was only one case of bilateral HFS. This patient had an intervening span of 5 years before occurrence in the second side.

Clinical findings

By type of clinical onset, patients were classified into two groups: Typical syndrome and atypical syndrome. Typical HFS syndrome (onset in the upper hemiface, usually the lower eyelid, which progressed downward to affect the cheek and oral commissure) occurred in 177 patients (91.2%). Atypical syndrome (first affecting muscles of the mouth, then gradually spreading upward to the cheek and eyelid) occurred in 17 patients (8.8%). Two patients (1.0%) had tic convulsive.

Prior to surgery, pharmacological therapy (e.g. carbamazepine, benzodiazepine) was used, with poor response, in 108 patients (55.7%). Nineteen patients previously treated with botulinum toxin type A injections had satisfactory temporary results lasting 4–6 months in most cases. One patient underwent microvascular decompression at another institution without postoperative clinical improvement.

Preoperatively, all patients underwent audiological evaluation. Thirty-one patients had abnormal results on an auditory evoked potential test that suggested vascular compression; 28 patients were found to have ipsilateral nonuseful hearing; and the rest of the patients (n = 135) had a normal test. Four patients had tinnitus, 13 had facial hypoesthesia, and 13 had mild facial paralysis (House–Brackmann score < 3[

Preoperative imaging (computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging) showed no anomalies in 112 patients. Fifty-two patients had a vascular loop compressing the facial nerve root at its entry point at the brainstem, and 30 patients had basilar artery ectasia.

Surgical findings

All 194 patients underwent surgery for vascular decompression of the entry point of the facial nerve root at the brainstem. An operative microscope and microsurgical instruments were used, with the patient in the park-bench position. The first 18 procedures were approached through a lateral suboccipital craniectomy, and the subsequent 176 were accessed via a retrosigmoid asterional craniectomy (maximum diameter, 20–25 mm). In two patients, endoscopy was used to facilitate the procedure.

Vascular compression was identified in 185 patients. Nine patients showed no compression. In the 185 patients with vascular compression, the nerve root was isolated from the offending vessel by placing nonabsorbable material (Dacron [polyethylene terephthalate fiber] in 10 patients, Silastic [silicone rubber) in 15 patients, and Teflon [polytetrafluoroethylene] in 169 patients). Teflon was the preferred material because of its maneuverability and ease of use. In nine patients with no evidence of vascular compression, the surgeon performed compression of the facial nerve root to alleviate HFS.

The most commonly identified offending vessel was the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) (n = 147 patients [75.8%]), followed by the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) (n = 12 [6.2%]), the basilar artery (n = 10 [5.2%]), and the superior cerebellar artery (n = 8 [4.1%]). More than one vessel (AICA and basilar artery) was involved in eight patients (4.1%), and no identifiable offending vessel was found in nine patients (4.6%).

Postoperative outcomes

After the first surgery, all conservative treatment was discontinued. The 4-point outcomes scale identified excellent results in 155 patients (79.9%), good results in 9 (4.6%), and bad results in 30 (15.5%). Of the 30 patients with bad results, 1 died after the first surgery. The remaining 29 patients underwent a reintervention using the same approach within a period of 2–7 days postoperatively. No additional vascular compression or other factors were evident that could explain the lack of response. Compression of the facial nerve root was therefore performed in all 29 patients, with excellent results in 26 patients and bad results in 3 patients who required a third surgery that resulted in excellent outcomes for all 3, for a total of 226 surgeries in 194 patients. During follow-up, 21 other patients (10.8%) had recurrence after initial surgery within 2 months to 3 years after surgery but declined additional surgeries.

Complications

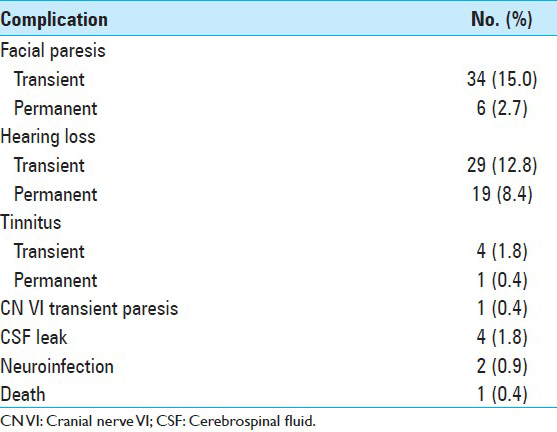

Complications included paresis (House–Brackman score < 3) in 34 patients, with onset on postoperative day 1, with improvement during the first month of follow-up in 28 patients (mean, 4.5 days [range, 1–30 days]). Marked hearing loss developed in 29 patients, 10 of whom fully recovered postoperatively in the first month, and 19 of whom continued to have nonuseful hearing by audiometry at 6-month follow-up. Tinnitus was present in four patients, three of whom had complete resolution at 1-month follow-up. Other complications are summarized in

DISCUSSION

HFS is a relatively rare entity that occurs most commonly in middle-aged women. According to Auger and Whisnant,[

The pathogenesis of HFS, as described by Jannetta and colleagues,[

The diagnosis of HFS is clinical; electrophysiology and imaging studies are required to assess other pathologies of the cerebellopontine angle. In our study, no patients had associated tumors, aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations, arachnoid cysts, gliomas, brainstem strokes, or multiple sclerosis, which have been reported in previous studies of HFS.[

Therapeutic options include medication, botulinum toxin type A injections, and surgical decompression. The most commonly used medications are carbamazepine, phenytoin, baclofen, and clonazepam.[

In our series, the most commonly offending vessel was the AICA (75.8%). Other affected vessels were the PICA (6.2%), the basilar artery (5.2%), and the superior cerebellar artery (4.1%). Similar findings have been reported by Wilson et al.[

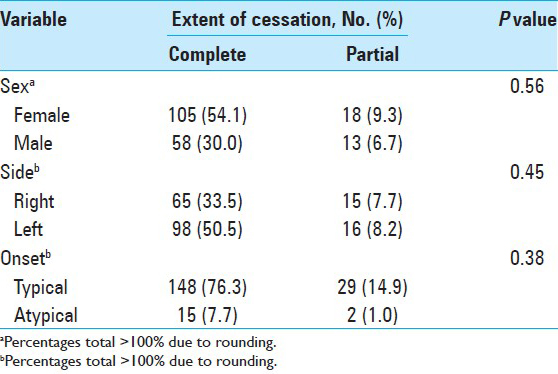

Reports of complete cessation of spasms document success rates of more than 50%, from lows of 60% (Loeser and Chen[

Ishikawa and colleagues[

In our study, the rate of permanent deficits was similar to those reported by Barker et al.,[

CONCLUSIONS

Limitations of this study include those inherent to its retrospective nature and its inclusion of only a Hispanic population. Nonetheless, to our knowledge, this is the largest series to date on HFS in a Hispanic population. Previous reports have not analyzed the unique features of HFS in this population, which makes this study relevant to address the lack of knowledge in the field.

Additional studies are needed to fully understand the nature of HFS, the response of patients to different treatment options, and the development of recurrence. So far, microvascular decompression offers the best long-term outcome for treatment of HFS, with low morbidity and mortality. Ongoing improvements in surgical techniques allow microvascular decompression to be performed through a minimally invasive approach. The most commonly implicated vessel is the AICA. Postoperative complications may be related to the experience of the surgeon, the necessity for reoperation, and the use of a refined surgical technique. Factors related to nonresponse or recurrence remain unknown. However, if surgery does not relieve the spasm during the first week, we recommend immediate reexploration.

References

1. Alexander GE, Moses H. Carbamazepine for hemifacial spasm. Neurology. 1982. 32: 286-7

2. Auger RG. Hemifacial spasm: Clinical and electrophysiologic observations. Neurology. 1979. 29: 1261-72

3. Auger RG, Piepgras DG, Laws ER, Miller RH. Microvascular decompression of the facial nerve for hemifacial spasm: Clinical and electrophysiologic observations. Neurology. 1981. 31: 346-50

4. Auger RG, Whisnant JP. Hemifacial spasm in Rochester and Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1960 to 1984. Arch Neurol. 1990. 47: 1233-4

5. Bandini F, Mazzella L. Gabapentin as treatment for hemifacial spasm. Eur Neurol. 1999. 42: 49-51

6. Barker FG, Jannetta PJ, Bissonette DJ, Shields PT, Larkins MV, Jho HD. Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg. 1995. 82: 201-10

7. Carter JB, Patrinely JR, Jankovic J, McCrary JA, Boniuk M. Familial hemifacial spasm. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990. 108: 249-50

8. Cook BR, Jannetta PJ. Tic convulsif: Results in 11 cases treated with microvascular decompression of the fifth and seventh cranial nerves. J Neurosurg. 1984. 61: 949-51

9. Cushing H. The major trigeminal neuralgias and their surgical treatment based on experiences with 332 Gasserian operations. Am J Med Sci. 1920. 160: 157-84

10. Deeb ZL, Jannetta PJ, Rosenbaum AE, Kerber CW, Drayer BP. Tortuous vertebrobasilar arteries causing cranial nerve syndromes: Screening by computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1979. 3: 774-8

11. Digre K, Corbett JJ. Hemifacial spasm: Differential diagnosis, mechanism, and treatment. Adv Neurol. 1988. 49: 151-76

12. Fabinyi GC, Adams CB. Hemifacial spasm: Treatment by posterior fossa surgery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1978. 41: 829-33

13. Fairholm D, Wu JM, Liu KN. Hemifacial spasm: Results of microvascular relocation. Can J Neurol Sci. 1983. 10: 187-91

14. Friedman A, Jamrozik Z, Bojakowski J. Familial hemifacial spasm. Mov Disord. 1989. 4: 213-8

15. Gardner WJ. Concerning the mechanism of trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg. 1962. 19: 947-58

16. Herzberg L. Management of hemifacial spasm with clonazepam. Neurology. 1985. 35: 1676-7

17. Higashi S, Yamashita J, Yamamoto Y, Izumi K. Hemifacial spasm associated with a cerebellopontine angle arachnoid cyst in a young adult. Surg Neurol. 1992. 37: 289-92

18. Hjorth RJ, Willison RG. The electromyogram in facial myokymia and hemifacial spasm. J Neurol Sci. 1973. 20: 117-26

19. House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985. 93: 146-7

20. Huang CI, Chen IH, Lee LS. Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm: Analyses of operative findings and results in 310 patients. Neurosurgery. 1992. 30: 53-6

21. Illingworth RD, Porter DG, Jakubowski J. Hemifacial spasm: A prospective long-term follow up of 83 cases treated by microvascular decompression at two neurosurgical centres in the United Kingdom. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996. 60: 72-7

22. Ishikawa M, Nakanishi T, Takamiya Y, Namiki J. Delayed resolution of residual hemifacial spasm after microvascular decompression operations. Neurosurgery. 2001. 49: 847-54

23. Iwakuma T, Matsumoto A, Nakamura N. Hemifacial spasm. Comparison of three different operative procedures in 110 patients. J Neurosurg. 1982. 57: 753-6

24. Jannetta PJ. The cause of hemifacial spasm: Definitive microsurgical treatment at the brainstem in 31 patients. Trans Sect Otolaryngol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1975. 80: 319-22

25. Jannetta PJ. Outcome after microvascular decompression for typical trigeminal neuralgia, hemifacial spasm, tinnitus, disabling positional vertigo, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia (honored guest lecture). Clin Neurosurg. 1997. 44: 331-83

26. Jannetta PJ. Typical or atypical hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg. 1998. 89: 346-7

27. Jannetta PJ, Kassam A. Hemifacial spasm. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999. 66: 255-6

28. Jho HD, Jannetta PJ. Hemifacial spasm in young people treated with microvascular decompression of the facial nerve. Neurosurgery. 1987. 20: 767-70

29. Kaye AH, Adams CB. Hemifacial spasm: A long term follow-up of patients treated by posterior fossa surgery and facial nerve wrapping. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981. 44: 1100-3

30. Kim P, Fukushima T. Observations on synkinesis in patients with hemifacial spasm. Effect of microvascular decompression and etiological considerations. J Neurosurg. 1984. 60: 821-7

31. Kobata H, Kondo A, Kinuta Y, Iwasaki K, Nishioka T, Hasegawa K. Hemifacial spasm in childhood and adolescence. Neurosurgery. 1995. 36: 710-4

32. Kondo A. Follow-up results of microvascular decompression in trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm. Neurosurgery. 1997. 40: 46-51

33. Kraft SP, Lang AE. Cranial dystonia, blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm: Clinical features and treatment, including the use of botulinum toxin. Cmaj. 1988. 139: 837-44

34. Langston JW, Tharp BR. Infantile hemifacial spasm. Arch Neurol. 1976. 33: 302-3

35. Loeser JD, Chen J. Hemifacial spasm: Treatment by microsurgical facial nerve decompression. Neurosurgery. 1983. 13: 141-6

36. Lundberg PO, Westerberg CE. A hereditary neurological disease with facial spasm. J Neurol Sci. 1969. 8: 85-100

37. Magun R, Esslen E. Electromyographic study of reinnervated muscle and of hemifacial spasm. Am J Phys Med. 1959. 38: 79-86

38. Mauriello JA, Aljian J.editors. Natural history of treatment of facial dyskinesias with botulinum toxin: A study of 50 consecutive patients over seven years. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991. 75: 737-9

39. Millan-Guerrero RO, Tene-Perez E, Trujillo-Hernandez B. Levodopa in hemifacial spasm. A therapeutic alternative. Gac Med Mex. 2000. 136: 565-71

40. Moller AR. Hemifacial spasm: Ephaptic transmission or hyperexcitability of the facial motor nucleus?. Exp Neurol. 1987. 98: 110-9

41. Moller AR, Jannetta PJ. Microvascular decompression in hemifacial spasm: Intraoperative electrophysiological observations. Neurosurgery. 1985. 16: 612-8

42. Montagna P, Imbriaco A, Zucconi M, Liguori R, Cirignotta F, Lugaresi E. Hemifacial spasm in sleep. Neurology. 1986. 36: 270-3

43. Nagata S, Matsushima T, Fujii K, Fukui M, Kuromatsu C. Hemifacial spasm due to tumor, aneurysm, or arteriovenous malformation. Surg Neurol. 1992. 38: 204-9

44. Neagoy DR, Dohn DF. Hemifacial spasm secondary to vascular compression of the facial nerve. Cleve Clin Q. 1974. 41: 205-14

45. Nielsen VK. Electrophysiology of the facial nerve in hemifacial spasm: Ectopic/ephaptic excitation. Muscle Nerve. 1985. 8: 545-55

46. Revuelta-Gutierrez R, Vales-Hidalgo LO, Arvizu-Saldana E, Hinojosa-Gonzalez R, Reyes-Moreno I. Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. Ten years of experience. Cir Cir. 2003. 71: 5-10

47. Revuelta Gutierrez R, Soto-Hernandez JL, Suastegui-Roman R, Ramos-Peek J. Transient hemifacial spasm associated with subarachnoid brainstem cysticercosis: A case report. Neurosurg Rev. 1998. 21: 167-70

48. Rhoton AL. Microsurgical neurovascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm. J Fla Med Assoc. 1978. 65: 425-8

49. Rushworth RG, Smith SF. Trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm: Treatment by microvascular decompression. Med J Aust. 1982. 1: 424-6

50. Saito S, Moller AR. Chronic electrical stimulation of the facial nerve causes signs of facial nucleus hyperactivity. Neurol Res. 1993. 15: 225-31

51. Samii M, Gunther T, Iaconetta G, Muehling M, Vorkapic P, Samii A. Microvascular decompression to treat hemifacial spasm: Long-term results for a consecutive series of 143 patients. Neurosurgery. 2002. 50: 712-8

52. Sanders DB. Ephaptic transmission in hemifacial spasm: A single-fiber EMG study. Muscle Nerve. 1989. 12: 690-4

53. Sandyk R, Gillman MA. Baclofen in hemifacial spasm. Int J Neurosci. 1987. 33: 261-4

54. Shin JC, Chung UH, Kim YC, Park CI. Prospective study of microvascular decompression in hemifacial spasm. Neurosurgery. 1997. 40: 730-4

55. Taylor JD, Kraft SP, Kazdan MS, Flanders M, Cadera W, Orton RB.editors. Treatment of blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm with botulinum A toxin: A Canadian multicentre study. Can J Ophthalmol. 1991. 26: 133-8

56. Telischi FF, Grobman LR, Sheremata WA, Apple M, Ayyar R. Hemifacial spasm. Occurrence in multiple sclerosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991. 117: 554-6

57. Vermersch P, Petit H, Marion MH, Montagne B. Hemifacial spasm due to pontine infarction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991. 54: 1018-

58. Westra I, Drummond GT. Occult pontine glioma in a patient with hemifacial spasm. Can J Ophthalmol. 1991. 26: 148-51

59. Wilkins RH. Hemifacial spasm: A review. Surg Neurol. 1991. 36: 251-77

60. Wilson CB, Yorke C, Prioleau G. Microsurgical Vascular Decompression for Trigeminal Neuralgia and Hemifacial Spasm. West J Med. 1980. 132: 481-7

61. Woltman HW, Williams HL, Lambert EH. An attempt to relieve hemifacial spasm by neurolysis of the facial nerves; a report of two cases of hemifacial spasm with reflections on the nature of the spasm, the contracture and mass movement. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1951. 26: 236-40