- Department of Neurosurgery, Ruth and Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel

- Department of Neurosurgery, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York, USA

Correspondence Address:

Jonathan Nakhla

Department of Neurosurgery, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York, USA

DOI:10.4103/sni.sni_386_16

Copyright: © 2017 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Avra S. Laarakker, Jonathan Nakhla, Andrew Kobets, Rick Abbott. Incidental choroid plexus papilloma in a child: A difficult decision. 26-May-2017;8:86

How to cite this URL: Avra S. Laarakker, Jonathan Nakhla, Andrew Kobets, Rick Abbott. Incidental choroid plexus papilloma in a child: A difficult decision. 26-May-2017;8:86. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/incidental-choroid-plexus-papilloma-in-a-child-a-difficult-decision/

Abstract

Background:Choroid plexus tumors (CPT) in the pediatric population are usually discovered in symptomatic patients often with symptoms of increased intracranial pressure, with hydrocephalus as the most common presentation, along with seizures, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or focal neurological deficit. Most CPTs are found to be benign choroid plexus papillomas (CPP), whereas a small number are intermediate and malignant choroid plexus carcinomas (CPC). Total surgical resection is the established definitive treatment for symptomatic CPP.

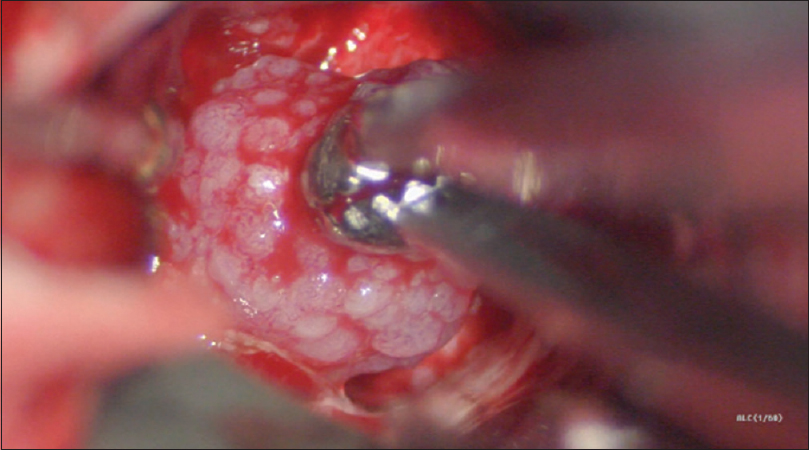

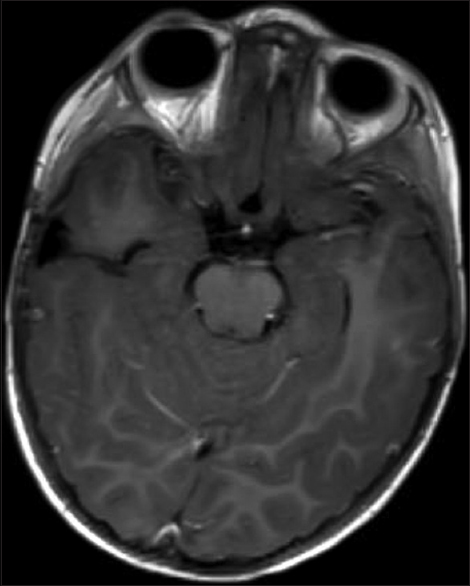

Case Description:We describe a young female who was found to have an incidental CPT during workup for recent head trauma without neurological deficits or hydrocephalus. She underwent a surgical operation to remove the tumor successful, with 1-year follow-up showing no recurrence and normal developmental milestones.

Conclusion:This rare presentation of an asymptomatic CPT brings attention to the fact that there is no clear evidence for how or when to treat such patients. Because discovery of a CPT in an asymptomatic patient is uncommon, the treatment plan appears to be developed on a case-by-case basis. We hope to generate discussion for establishing an agreed upon treatment approach for CPTs in asymptomatic patients.

Keywords: Child nervous system, choroid plexus papilloma, choroid plexus tumor, incidental, oncology

INTRODUCTION

Choroid plexus tumors (CPT) in the pediatric population are usually discovered, unfortunately, when patients present symptomatically. Symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) with hydrocephalus are the most common presentation, along with seizures, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), or focal neurological deficit.[

CASE REPORT

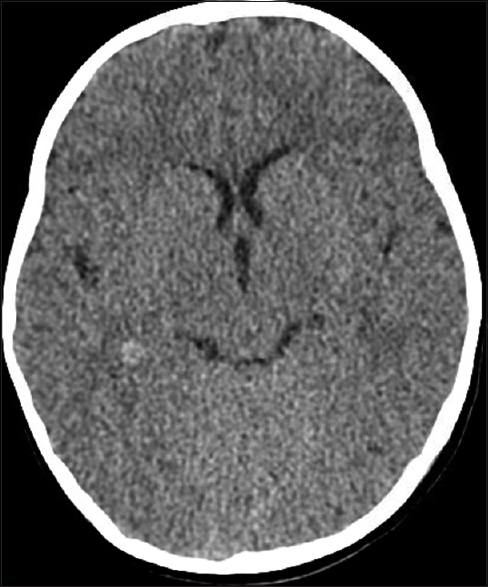

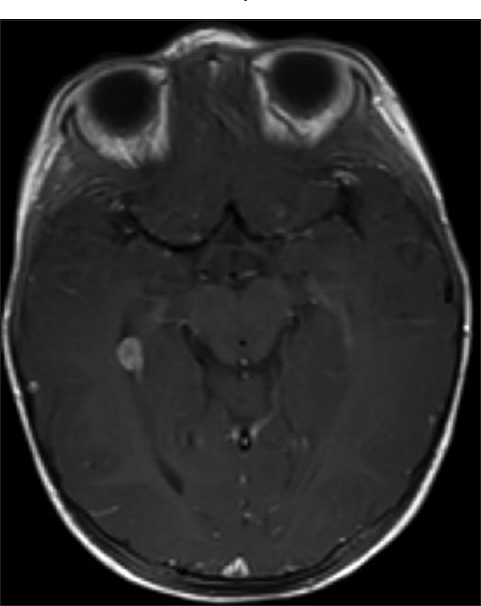

An 11-month-old girl presented to the emergency room bleeding from her ear 2 days after an accidental fall rolling off the bed and striking her head. The patient was otherwise healthy with no relevant medical, birth, or social history. An initial computed tomography (CT) of the head was negative for hemorrhage [

DISCUSSION

CPTs are rare, according to the Canadian Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium experience, the annual age-adjusted incidence rate was 0.22+0.12 (95% CI 0.16–0.28)/100,000 in children less than 3 years of age.[

In the case of an incidentally found CPT, there is no evidence indicating whether prompt surgical removal is best, or that surgery should be withheld until routine surveillance shows either radiographic changes in the tumor, an increase in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume (hydrocephalus), or the patient becomes symptomatic.

The benefit to waiting until hydrocephalus develops is that it lessens the length of the corridor to the ventricles and increases the space around the tumor giving greater access to its blood supply. This may allow for an easier resection of the CPT. The drawback to this is that hydrocephalus may not be the presenting symptom, and that the first neurological insult from mass effect, a SAH, or seizures may result in focal deficits that do not resolve after removal of the tumor. Furthermore, there is some evidence that cognitive deficits and regression may develop as these tumors grow.[

Matsuyama et al. reported a case of an incidentally found CPP in a 19-year-old patient. The CPP extended from the third ventricle into the right lateral ventricle. The tumor was operated on promptly. They reported that the slightly enlarged right lateral ventricle contributed to the decision as this made the tumor more accessible.[

There may be a role for preoperative embolization to reduce the amount of intraoperative blood loss, and is therefore, associated with higher rates of total resection and lower operative morbidity and mortality.[

Radiosurgery may also be a possible treatment for CPTs, however, little is known about the efficacy or use in asymptomatic patients as the risks may outweigh the benefits of use.[

This rare presentation of an asymptomatic CPT brings attention to the fact that there is no clear evidence for how or when to treat such patients. We opted to operate promptly, but electively, to prevent any long-term sequelae from the CPT. A clear treatment plan is established for symptomatic patients but is not as well developed for asymptomatic patients. As discovery of a CPT in an asymptomatic patient is extremely rare, the treatment plan appears to be developed on a case-by-case basis. For the initial workup, even in the asymptomatic patient, it may be that an MRI scan is warranted when a hyperdense lesion near a ventricle is discovered, as was done for our patient. In the event that an MRI is not performed, a follow- up CT scan should be done to monitor for changes or to confirm the resolution of blood if hemorrhage was suspected.

CONCLUSION

After our literature search, we were still unclear on how to proceed given the paucity of data on the natural history of these tumors. We made our decision given that as the tumor grows and will ultimately require surgery, the psychological trauma to the child is minimized by operating in this age group as well as the need for tissue diagnosis. As a small percentage of these may be high grade, it is worth the risk to identify this patient earlier, especially because the extent of resection is significantly associated with increased survival.[

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Greenberg MS.editorsHandbook of Neurosurgery, ed. New York, NY: Thieme Publishers; 2010. p.

2. Kim IY, Niranjan A, Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC, Lunsford LD. Gamma knife radiosurgery for treatment resistant choroid plexus papillomas. J Neurooncol. 2008. 90: 105-10

3. Lafay-Cousin L, Keene D, Carret AS, Fryer C, Brossard J, Crooks B. Choroid plexus tumors in children less than 36 months: The Canadian Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium (CPBTC) experience. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011. 27: 259-64

4. Lam S, Lin Y, Cherian J, Qadri U, Harris DA, Melkonian S. Choroid plexus tumors in children: A population-based study. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2013. 49: 331-8

5. Matsuyama T, Masuda A. A rare case of choroid plexus papilloma in the third ventricle. No Shinkei Geka. 1992. 20: 1269-72

6. Nagib MG, O’Fallon MT. Lateral ventricle choroid plexus papilloma in childhood: Management and complications. Surg Neurol. 2000. 54: 366-72

7. Slater LA, Hoffman C, Drake J, Krings T. Pre-operative embolization of a choroid plexus carcinoma: Review of the vascular anatomy. Childs Nerv Syst. 2016. 32: 541-5

8. Strojan P, Popovic M, Surlan K, Jereb B. Choroid plexus tumors: A review of 28-year experience. Neoplasma. 2004. 51: 306-12

9. Wrede B, Liu P, Wolff JE. Chemotherapy improves the survival of patients with choroid plexus carcinoma: A meta-analysis of individual cases with choroid plexus tumors. J Neurooncol. 2007. 85: 345-51