- Department of Neurosurgery, Kurume University School of Medicine, Kurume, Japan

- Uchikado Neuro-Spine Clinic, Fukuoka, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Koki Satake, Department of Neurosurgery, Kurume University School of Medicine, Kurume, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_728_2023

Copyright: © 2023 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Koki Satake1, Hisaaki Uchikado2, Natsuko Miyahara1, Takehiro Makizono1, Motohiro Morioka1, Takahiro Miyahara1. Intractable hiccup caused by syrinx in Chiari type I malformation. Two cases report. 06-Oct-2023;14:355

How to cite this URL: Koki Satake1, Hisaaki Uchikado2, Natsuko Miyahara1, Takehiro Makizono1, Motohiro Morioka1, Takahiro Miyahara1. Intractable hiccup caused by syrinx in Chiari type I malformation. Two cases report. 06-Oct-2023;14:355. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/12582/

Abstract

Background: Intractable hiccups (IH) due to syringomyelia or syringomyelia/syringobulbia associated with Chiari type I malformations (CMI) are extremely rare. Here, we present two patients who presented with IH; one had a CMI with syringomyelia/syringobulbia, and the other, with CMI and syringomyelia.

Case Description: The first patient was an 18-year-old female who presented with IH attributed to a holocord syrinx and syringobulbia involving the right dorsolateral medulla. The second patient was a 22-year-old female with a C3-5 syringomyelia. Both patients successfully underwent foramen magnum decompressions that improved their symptoms, while subsequent magnetic resonance studies confirmed shrinkage of their syringobulbia/syringomyelia cavities.

Conclusion: IH was due to cervical syringomyelia/syringobulbia in one patient and cervical syringomyelia in the other; both were successfully managed with foramen magnum decompressions.

Keywords: Chiari type I malformation, Intractable hiccups, Lateral medullary syndrome, Syringobulbia, Syringomyelia

INTRODUCTION

Intractable hiccups (IH) are rarely due to Chiari I malformation (CMI) in conjunction with cervical syringomyelia/dorsal medullary syringobulbia and/or cervical syringomyelia.[

CASE REPORT

Case 1

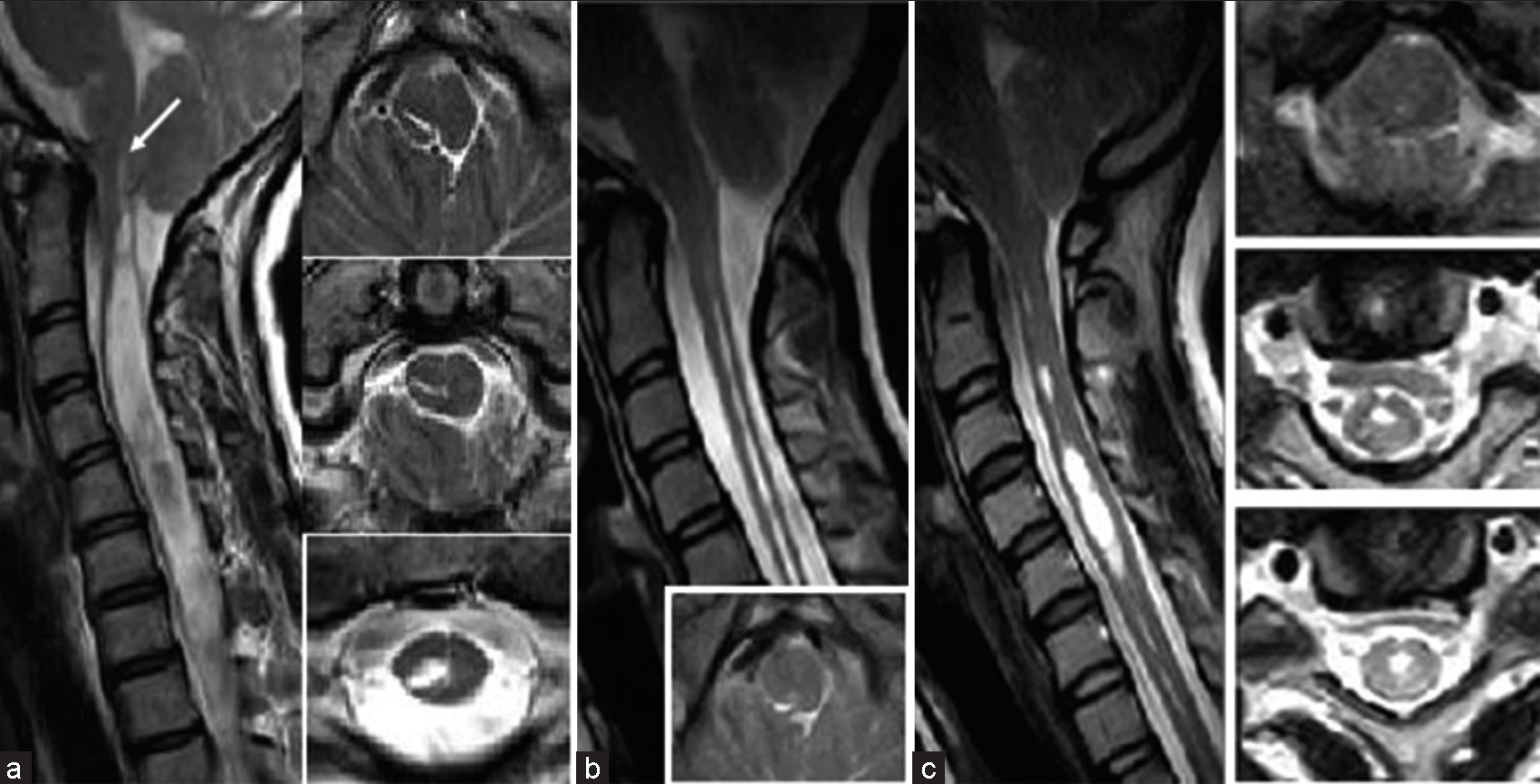

An 18-year-old female presented with 6 months of hiccups, and difficulty writing due to the distal right upper extremity muscle atrophy. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a CMI with a holocord syrinx and a slit-like cavum on the dorsal lateral side of the right medulla (syringobulbia) [

Figure 1:

(a) Case 1: Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the cervical spine. T2-weighted MRI scan in the sagittal plane, showing a Chiari type I malformation (CMI) and a holocord syrinx with syringobulbia (arrow). An axial MRI scan was obtained at the foramen magnum level, demonstrating the slit-like syrinx in the right dorsal region of the lower medulla. (b) Case 1: Postoperative MRI scans of the cervical spine obtained 3 months after surgery. T2-weighted MRI scan in the sagittal plane, demonstrating decompression of medulla oblongata and cerebellar tonsils at the foramen magnum. The syringobulbia has collapsed. The cervical syringomyelia is slightly decreased in size but remains and (c) Case 2: MRI scans of the cervical spine. T2-weighted MRI scan in the sagittal plane, showing a CMI and a syrinx from the high cervical to the C3-5 level. Axial MRI scan was obtained at the foramen magnum and C3-5 level, demonstrating the syrinx in the mid-ventral region.

Case 2

A 22-year-old female presented with 2 months of hiccups, and 3 months of dizziness accompanied by the right upper extremity numbness. The MRI showed a CMI and a cervical syrinx from C3 to 5 [

DISCUSSION

Symptoms and pathophysiology of CMIs

CMI is the most common etiology of cerebellar tonsil herniation at the craniovertebral junction. Accompanying syringomyelia is diagnosed in 20–50% of these patients. Clinical symptoms of CMI with syringomyelia include cough, headache/occipitalgia, gait disturbances/ataxia, dissociated sensory disorders, dysphagia, and paresis of the extremities.[

Pathophysiology of hiccups

Hiccups are defined as intractable when they; persist for more than 24 h, when the rate increases from 40 to 100/min, and/or when they become refractory to usual methods of treatment.[

CM1 with hiccups

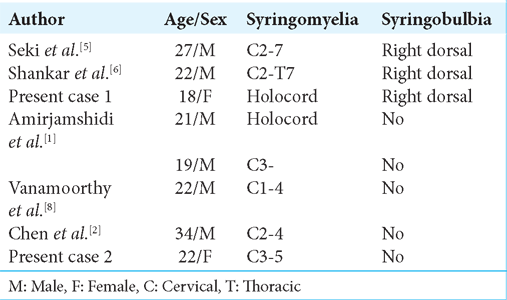

We have added two patients to the six cases previously reported who presented with both IH and CMI [

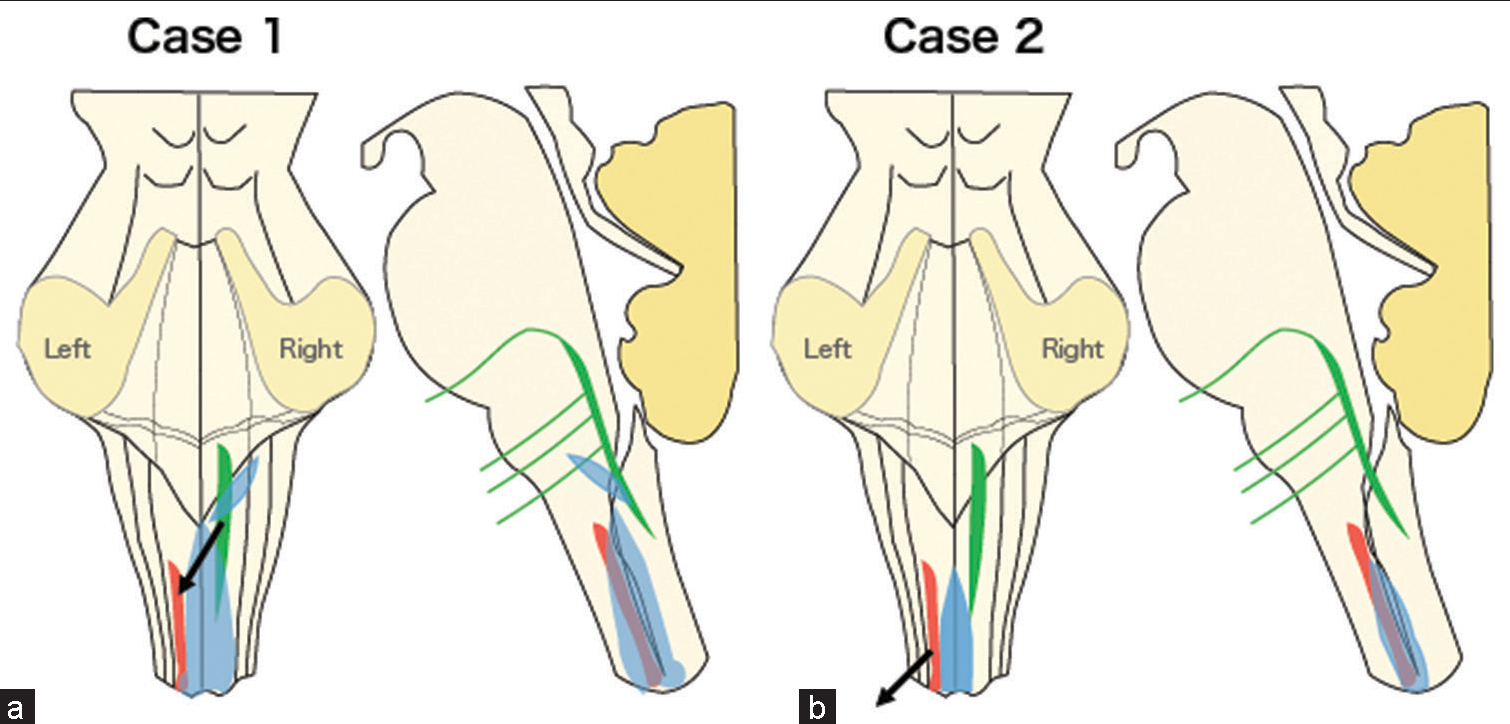

Figure 2:

The schema of pathophysiological mechanisms for hiccups due to syrinx with Chiari type I malformation (CMI). (a) Case 1: CMI with syringomyelia and syringobulbia (blue) and (b) Case 2: CMI with syringomyelia (blue). “Hiccup center” accessory nucleus (red) in the upper spinal cord (C3-C5), nucleus solitarius (green) in the medulla oblongata near the respiratory center. The stimulation to hiccup reflex (black arrow).

CONCLUSION

Two young females, 18 and 22 years of age respectively, presented with IH attributed to CMI/syringomyelia and CMI/syringomyelia/syringobulbia; both were successfully treated with foramen magnum decompressions.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The author(s) confirms that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Amirjamshidi A, Abbassioun K, Parsa K. Hiccup and neurosurgeons: A report of 4 rare dorsal compressive pathologies and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2007. 67: 395-402 discussion 402

2. Chen Z, Shang H, Zhao W, Wu Z, Wei Y, Chen B. Intractable hiccups associated with Chiari Type I malformation: Case report and literature review. World Neurosurg. 2018. 118: 329-31

3. Moon CO, Hwang SH, Hong SS, Jung S, Kwon SB. Lesional location of intractable hiccups in acute pure lateral medulluary infarction. Neurol Asia. 2014. 19: 343-9

4. Rajagopalan V, Sengupta VD, Goyal K, Dube SK, Bindra A, Kedia S. Hiccups in neurocritical care. J Neurocrit Care. 2021. 14: 18-28

5. Seki T, Hida K, Lee J, Iwasaki Y. Hiccups attributable to syringobulbia and/or syringomyelia associated with a Chiari I malformation: Case report. Neurosurgery. 2004. 54: 224-6 discussion 226-7

6. Shankar B, Narayanan R, Paruthikunnan SM, Kulkarni CD. Persistent singultus as presenting symptom of syringobulbia. BMJ Case Rep. 2014. 2014: bcr2014205314

7. Steger M, Schneemann M, Fox M. Systemic review: The pathogenesis and pharmacological treatment of hiccups. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015. 42: 1037-50

8. Vanamoorthy P, Kar P, Prabhakar H. Intractable hiccups as presenting symptom of Chiari I malformation. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008. 150: 1207-8