- Department of Neurosciences, Reproductive and Odontostomatological Sciences, Federico II University, Naples, Italy.

- Department of Neurosurgery, Messina University - Policlinico G. Martino, Messina, Italy.

- Maxillofacial Surgery Unit, Department of Neurosciences, Reproductive and Odontostomatological Sciences, Federico II University, Naples, Italy.

- Department of Neurosurgery, Santa Maria delle Grazie Hospital, Pozzuoli, Italy.

- Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, Santa Maria delle Grazie Hospital, Pozzuoli, Italy.

Correspondence Address:

Giuseppe Corazzelli, Department of Neurosciences, Reproductive and Odontostomatological Sciences, Università Degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Naples, Italy.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_965_2023

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Giuseppe Corazzelli1, Sergio Corvino1, Giulio Di Noto2, Cristiana Germano3, Simona Buonamassa4, Salvatore Di Colandrea5, Raffaele de Falco4, Antonio Bocchetti4. Massive bilateral paraclinoidal subdural empyema and parenchymal temporopolar abscess with anatomical infection pathway in a chronic inhaling cocaine-addicted patient: A case report and literature review. 09-Feb-2024;15:42

How to cite this URL: Giuseppe Corazzelli1, Sergio Corvino1, Giulio Di Noto2, Cristiana Germano3, Simona Buonamassa4, Salvatore Di Colandrea5, Raffaele de Falco4, Antonio Bocchetti4. Massive bilateral paraclinoidal subdural empyema and parenchymal temporopolar abscess with anatomical infection pathway in a chronic inhaling cocaine-addicted patient: A case report and literature review. 09-Feb-2024;15:42. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/12733/

Abstract

Background: Focal suppurative bacterial infections of the central nervous system (CNS), such as subdural empyemas and brain abscesses, can occur when bacteria enter the CNS through sinus fractures, head injuries, surgical treatment, or hematogenous spreading. Chronic cocaine inhalation abuse has been linked to intracranial focal suppurative bacterial infections, which can affect neural and meningeal structures.

Case Description: We present the case of a patient who developed a cocaine-induced midline destructive lesion, a vast bilateral paraclinoidal subdural empyema, and intracerebral right temporopolar abscess due to cocaine inhalation abuse. The infection disseminated from the nasal and paranasal cavities to the intracranial compartment, highlighting a unique anatomical pathway.

Conclusion: The treatment involved an endoscopic endonasal approach, followed by a right frontal-temporal approach to obtain tissue samples for bacterial analysis and surgical debridement of the suppurative process. Targeted antibiotic therapy helped restore the patient’s neurological status.

Keywords: Cocaine addiction, Cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions, Subdural empyema, Temporopolar abscess

INTRODUCTION

Hematogenous spread, traumatic head injuries with skull and scalp discontinuity, and surgery are the primary causes of focal suppurative bacterial infections of the central nervous system (CNS).[

CASE REPORT

A 63-year-old male with a 10-year history of cocaine abuse presented with hyperpyrexia, seizures, and left hemiparesis. On admission, blood tests showed significant neutrophilic leukocytosis (28 × 103) and high C-reactive protein levels (346 mg/L). Once vital functions were stabilized and seizures were arrested, he underwent contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the head, which showed a right intra-axial temporopolar lesion (35 × 33 mm) with non-homogeneous contrast enhancement associated with digitiform perilesional edema and another large extra-axial bilateral frontal-basal lesion, which also presented non-homogeneous contrast enhancement. Moreover, extensive remodeling of the nasal and paranasal cavities, recognizable as cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions (CIMDL), and a hyperdense collection in the posterior aspect of the right maxillary sinus, spreading beyond the sphenopalatine foramen and pterygopalatine fossa through the orbital cavity and intracranial compartment were detected [

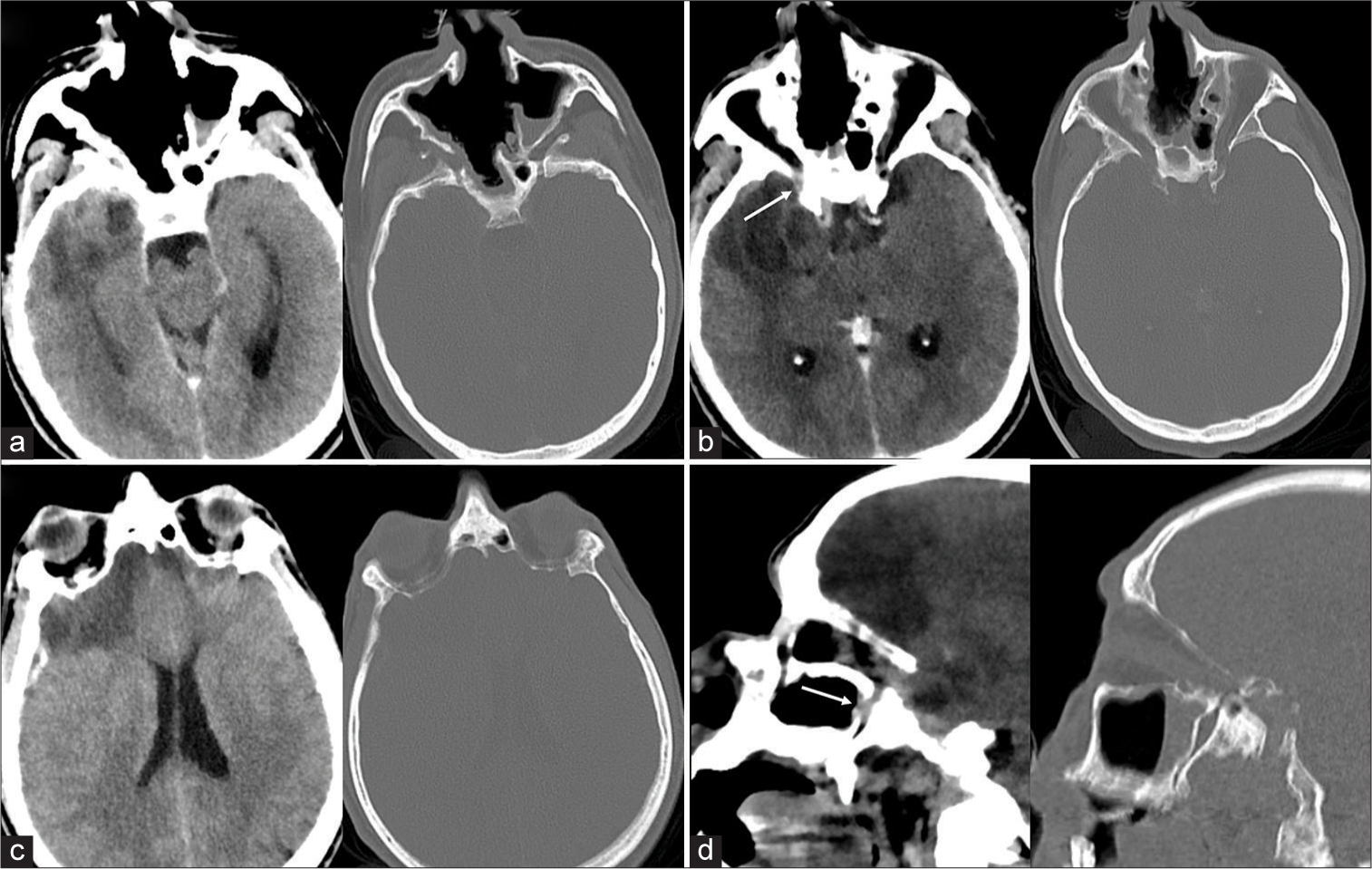

Figure 1:

Preoperative head contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan (“Parenchyma and soft structures” window, left; “Bone” window, right). (a) Axial sequence: There is evidence of extensive remodeling of the nasal and paranasal cavities, configuring the cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions setting, consisting of a whole nasal cavity, bilaterally fused with ethmoidal cells and maxillary sinuses. (b) Axial sequence: A right intraparenchymal temporopolar abscess (35 × 33 mm), with central hypodensity and peripheral contrast enhancement and massive perilesional edema; at the level of the posterior aspect of the orbital cavity, there appeared a contrast-enhancing collection, apparently spreading of the infective process (white arrow). (c) Axial sequence: There is a vast bifrontal hypodense extra-axial lesion with subdural empyhematous collection. (d) Sagittal view: A contrast-enhancing collection within the pterygopalatine fossa extends towards the posterior aspect of the orbital cavity and within the intracranial compartment, describing the presumed dissemination pathway of the infective process (white arrow).

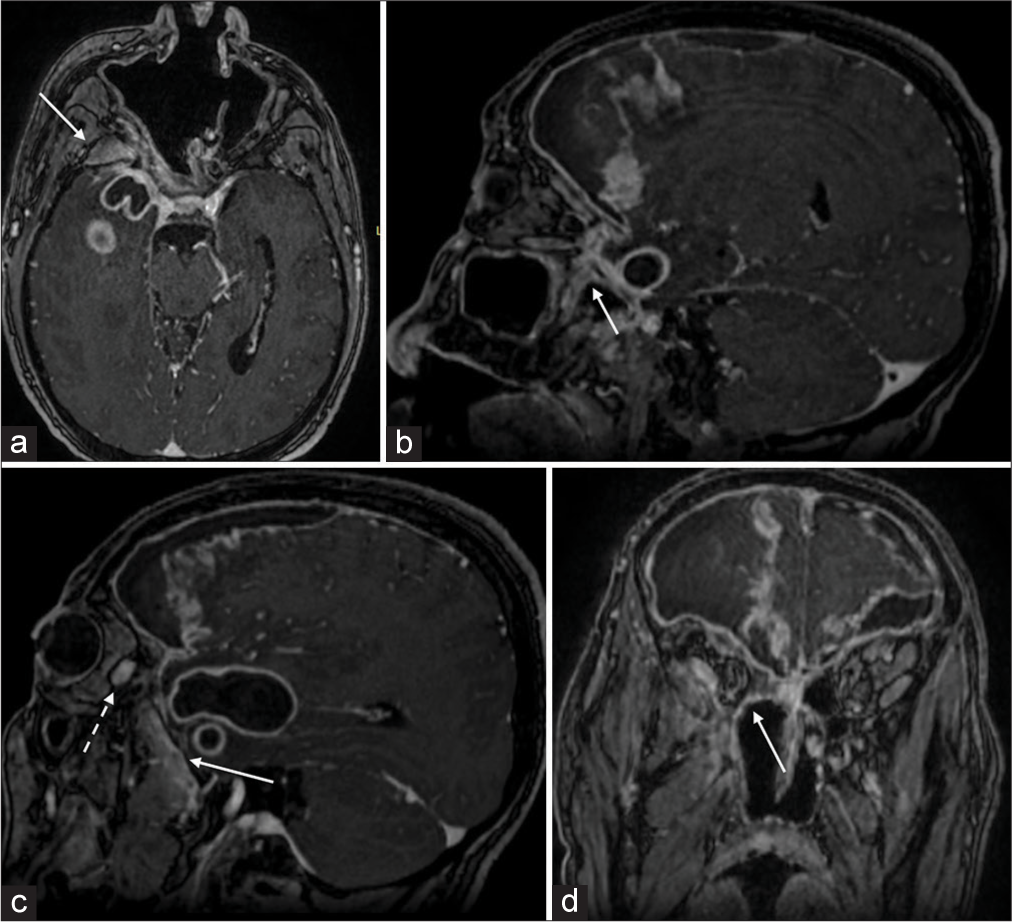

Figure 2:

Preoperative post contrast brain magnetic resonance imaging T1-weighted sequences: (a) Axial sequence: A significant contrast enhancement of the right pterygopalatine fossa (white arrow) in the context of the thickened contrasted right maxillary mucosa and the suppurative process extending beyond the right temporal pole. (b) Sagittal sequence, paramedian right: There is a wide subdural empyema in the frontal lobe, with central hyperintensity and peripheral contrast enhancing hyperintensity. It shows the spreading pathway of the infection through the rotundum foramen, which results in an enlarged and hyperintense (white arrow). (c) Sagittal sequence, mid pupillary right: there is an intra-axial temporopolar abscess at its largest diameter in the sagittal plane (40 × 20 mm) and the right side of the bilateral subdural empyema at the frontal lobe. Detail of the hyperintense pterygopalatine fossa in sagittal view (white arrow) and of a hyperintense collection within the posterior aspect of the right orbital cavity (dotted white arrow). (d) Coronal sequence: It shows the subdural empyema at its maximum extension on the coronal plane, characterized by strong peripheral hyperintensity, most pronunciation at the right frontal lobe, and the orbital spreading of the contrast-enhancing collection (white line).

Furthermore, a vast subdural empyema was detected in the bilateral frontal-basal and right paraclinoidal regions. The images also showed an infective process pathway through the intracranial compartment and right orbital cavity. There were no appreciable bony defects in the middle basicranium or clinically clear rhinoliquorrhea. The hyperintensity of the right pterygopalatine fossa and posterior aspect of the right orbital cavity on MRI suggested direct spreading of the suppuration. Indeed, the hypothesized dissemination pathway of the inflammatory process started from the maxillary sinus, proceeding through the sphenopalatine foramen toward the pterygopalatine fossa, and then upward through the inferior orbital fissure toward the posterior aspect of the orbital cavity and, lastly, spread posteriorly, and superiorly, through the superior orbital fissure, toward the middle cranial fossa [

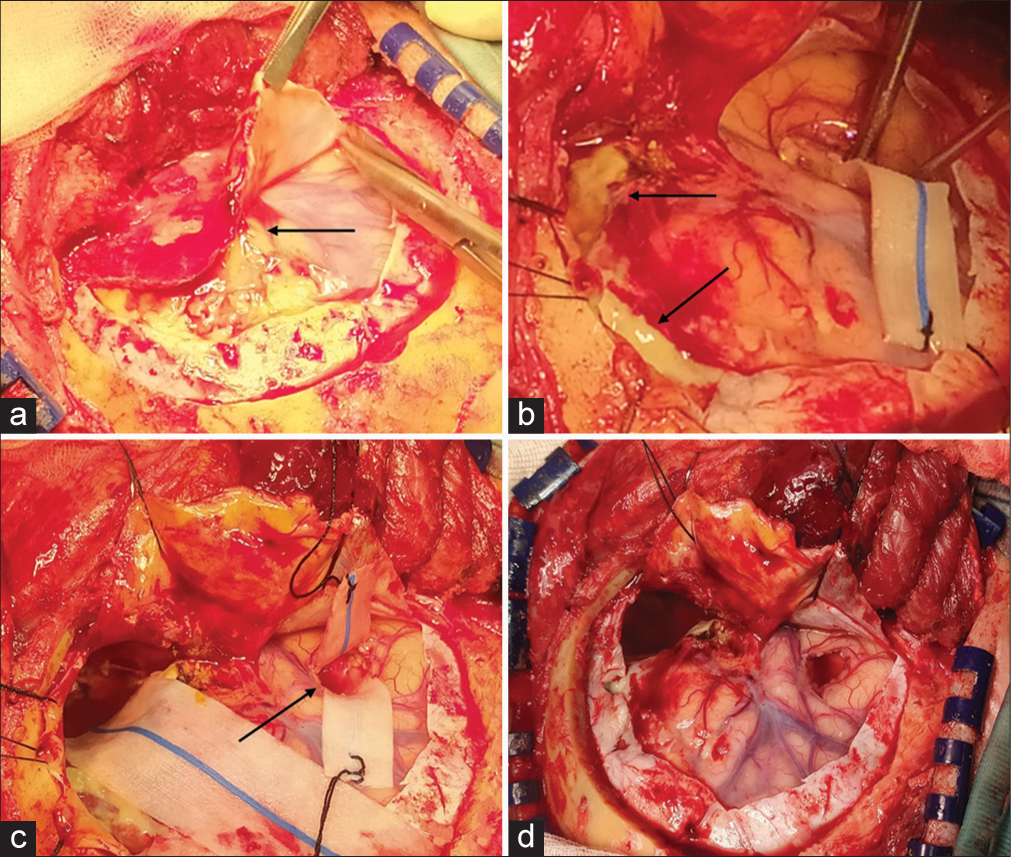

Figure 3:

Right frontal-temporal approach: (a) After performing a right frontal-temporal craniotomy, a yellowish fluid collection was sampled for cultural examination. The dura had a thick, reactive, and yellowish aspect, and a solid, parenchymatous lesion was appreciable with a net cleavage plan between empyema and healthy cerebral cortex (black arrow). (b) The empyema had a parenchymatous consistency and was also yellowish (black arrow). A significant phlogistic perilesional reaction was clear. The lesion was gradually and piecemeal evacuated. (c) After evacuating the empyema, a small right temporopolar corticectomy was performed (black arrow), and the content of the abscess capsule was aspirated and sent to the laboratory for cultural analysis. (d) After the piecemeal evacuation of the subdural empyema and aspiration of the temporopolar abscess, nervous structures, and Sylvian vein appeared well decompressed and pulsating. The reactive dura mater was replaced with a synthetic patch.

Blood tests on the 1st postoperative day showed a considerable decrease in C-reactive protein blood levels (49.84 mg/L) and white blood cell count (6.81 × 103). Postoperative head CT showed a sharp volume reduction of the extra-axial empyema collections and intra-axial abscess associated with regression of the central necrotic part and decreased intralesional septation. The patient’s neurological status progressively improved. Targeted antibiotic therapy successfully resolved the intraparenchymal abscess. The patient was dismissed due to an intact neurological status and an indication to follow targeted antibiotic treatment for the following 6 weeks.

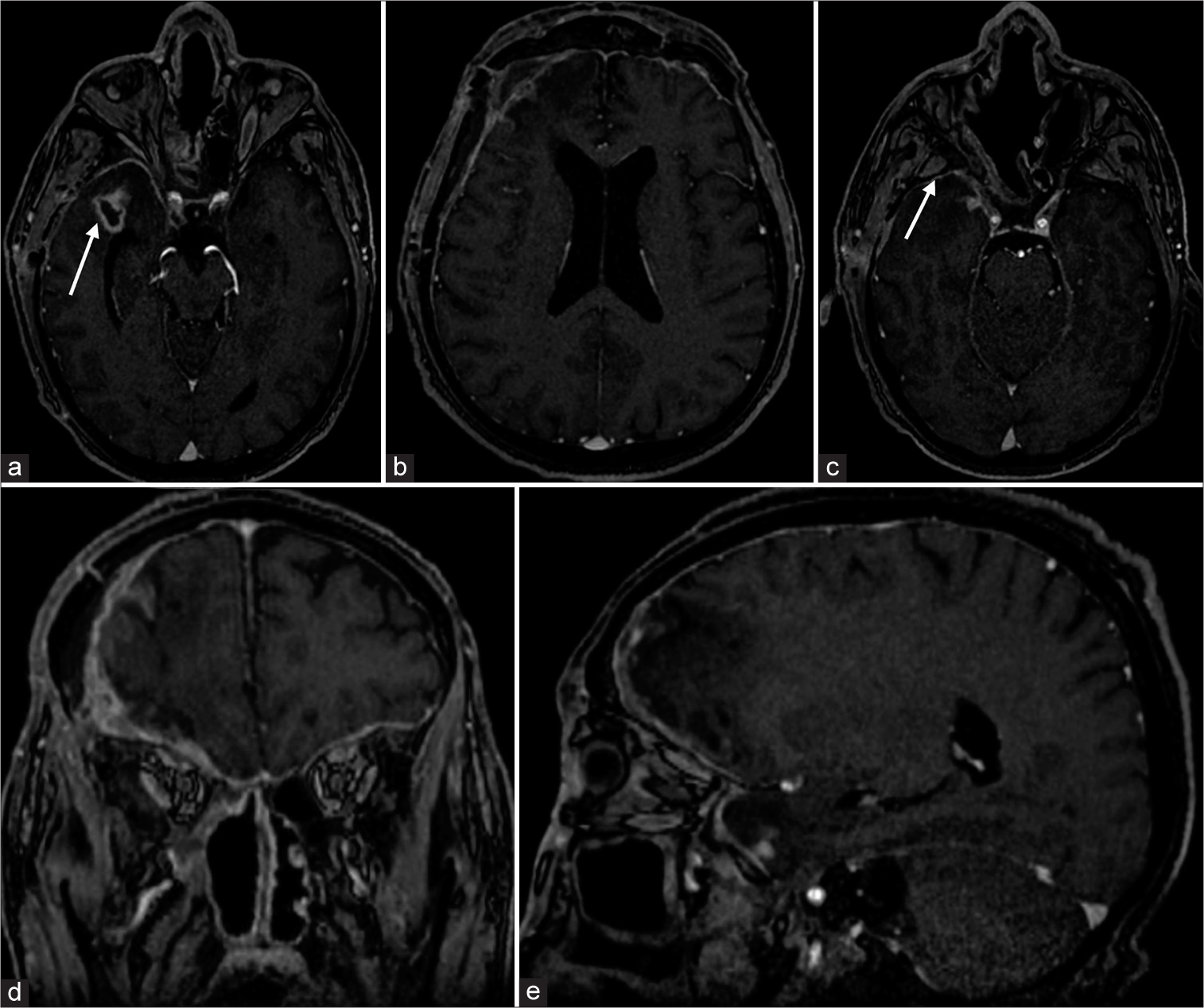

The 1-month postoperative MRI confirmed that the inflammation resolved in the pterygopalatine fossa and orbital cavity and showed a meaningful reduction in diameter on the axial plane of the temporopolar abscess (1.23 × 0.53 cm). Moreover, the subdural empyema located bilaterally in frontal-basal areas showed almost complete resolution, as well as infection of the right pterygopalatine fossa [

Figure 4:

One-month-postoperative post contrast brain magnetic resonance imaging T1-weighted sequences: (a) Axial sequence: 1-month-postoperative imaging showed a critical reduction in the diameter of the temporopolar abscess, in its largest diameter on the axial plane (1.23 × 0.53 cm), due to surgery and subsequent surgery antibiotic therapy (white arrow). (b) Axial sequence: The subdural lesion in the bilateral frontal-basal area showed almost complete resolution in its largest diameter on the axial plane. There was a dural thickening due to the inflammatory reaction in the surgical bed on the right frontal-temporal side. (c) Axial sequence: Antibiotic therapy also successfully resolved the infection among the right pterygopalatine fossa (white arrow). (d) Coronal sequence: The subdural empyema was resolved in the right frontal-temporal dural thickening due to the surgical approach and fibrotic reaction. (e) Sagittal sequence, paramedian right: Net volumetric reduction of infective lesions on the intracranial compartment and within the pterygopalatine fossa and orbital cavity.

DISCUSSION

Focal suppurative intracranial collections may cause various neurological conditions. A history of head trauma, prior infective disease, or immunodepletion mainly suggests the correct diagnosis.[

Cocaine has a devastating effect on the CNS, both physically and neuropsychologically. Its necrotizing action may also initiate suppuration of the necrotic brain parenchyma. Our case’s unity consisted of a peculiar anatomical spreading pathway of the infection. Moreover, this is the first case of subdural empyema and intraparenchymal abscess, both attributable to multiyear cocaine snorting abuse.

CONCLUSION

Inhaling cocaine abuse has devastating organic effects on CNS structures. Our case showed a peculiar spreading pathway of the suppurative process through the splanchnocranial cavities toward the orbital cavity and intracranial compartment, resulting in subdural empyema and an intraparenchymal abscess. Finally, it showed how the necrotizing action of cocaine might cause organic damage to the CNS and physically subvert the splanchnocranial and intracranial compartments.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Busl KM, Bleck TP. Bacterial infections of the central nervous system. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2013. 15: 612-30

2. Callaway CW, Clark RF. Hyperthermia in psychostimulant overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 1994. 24: 68-76

3. Esplin N, Stelzer JW, All S, Kumar S, Ghaffar E, Ali S. A case of Streptococcus anginosus brain abscess caused by contiguous spread from sinusitis in an immunocompetent patient. Cureus. 2017. 9: e1745

4. Fernández-de Thomas RJ, De Jesus O, editors. Subdural empyema. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. p.

5. Garcia-Perez D, Ruiz-Ortiz M, Panero I, Eiriz C, Moreno LM, Garcia-Reyne A. Snorting the brain away: Cerebral damage as an extension of cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2020. 79: 1365-9

6. LaPenna PA, Roos KL. Bacterial infections of the central nervous system. Semin Neurol. 2019. 39: 334-42

7. Levine SR, Brust JC, Futrell N, Ho KL, Blake D, Millikan CH. Cerebrovascular complications of the use of the “crack” form of alkaloidal cocaine. N Engl J Med. 1990. 323: 699-704

8. Mariniello G, Corvino S, Corazzelli G, Maiuri F. Cervical epidural abscess complicated by a pharyngoesophageal perforation after anterior cervical spine surgery for subaxial spondylodiscitis. Surg Neurol Int. 2023. 14: 102

9. Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Leon AC, Hirsch CS, Portera L, Iqbal MI. Ambient temperature and mortality from unintentional cocaine overdose. JAMA. 1998. 279: 1795-800

10. Moreno-Artero E, Querol-Cisneros E, Rodriguez-Garijo N, Tomas-Velazquez A, Antonanzas J, Secundino F. Mucocutaneous manifestations of cocaine abuse: A review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018. 32: 1420-6

11. Pruitt AA. Central nervous system infections in immunocompromised patients. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2021. 21: 37

12. Rana M, Mady A, Alharthy A, Ramadan O, Hashim W, Ashmawi S, editors. Brain abscess in a drug abuser with history of cocaine sniffing. Eur Radiol. 2014. p. Case 11786

13. Sordo L, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Barrio G, Kaye S, Ruiz-Perez I. A systematic review of evidence on the association between cocaine use and seizures. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013. 133: 795-804

14. Spennato P, De Paulis D, Bocchetti A, Michele Pipola A, Sica G, Galzio RJ. Spontaneous intracranial extradural haematoma associated with frontal sinusitis and orbital involvement. Neurol Sci. 2012. 33: 435-9

15. Suthar R, Sankhyan N. Bacterial infections of the central nervous system. Indian J ediatr. 2019. 86: 60-9

16. Zafar M, Vaughan S, Khuu B, Shrestha S, Porruvecchio E, Hadid A. Cocaine-induced pituitary and subdural brain abscesses and the treatment challenges. Cureus. 2021. 13: e20821