- Department of Neurosurgery and Neurooncology, Military University Hospital and First Faculty of Medicine Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic,

- Department of Veterinary Medicine, VetPark Clinic, Brandys nad Labem, Czech Republic.

Correspondence Address:

Ondřej Bradáč, Department of Neurosurgery and Neurooncology, Military University Hospital and First Faculty of Medicine Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_675_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Vladimír Beneš1, Martina Margoldová2, Ondřej Bradáč1, Petr Skalický1, Dominik Vlach2. Meningiomas in dogs. 08-Nov-2021;12:551

How to cite this URL: Vladimír Beneš1, Martina Margoldová2, Ondřej Bradáč1, Petr Skalický1, Dominik Vlach2. Meningiomas in dogs. 08-Nov-2021;12:551. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=11223

Abstract

Background: Meningiomas and gliomas are the two most common types of human intracranial tumors. However, meningiomas are not exclusively human tumors and are often seen in dogs and cats.

Methods: To present meningioma surgery in dogs and compare the surgical possibilities, tumor location, and to show the differences between human and veterinary approaches to tumor profiling. Eleven dogs with meningiomas were treated surgically for 5 years. All tumors except one were resected radically (Simpson 2). Localization of tumors mirrored that of human meningiomas.

Results: Two dogs died in direct relation to surgery. One died 14 months after surgery due to tumor regrowth. Three dogs died of unrelated causes 10–36 months after tumor resection and five dogs are alive and tumor-free 2–42 months after surgery.

Conclusion: Radical surgery in dogs is as effective as in humans. Thus, we propose that it should be implemented as first-line treatment. The article is meant to please all those overly curious neurosurgeons in the world.

Keywords: Dog, Meningioma, Radicality, Surgery

INTRODUCTION

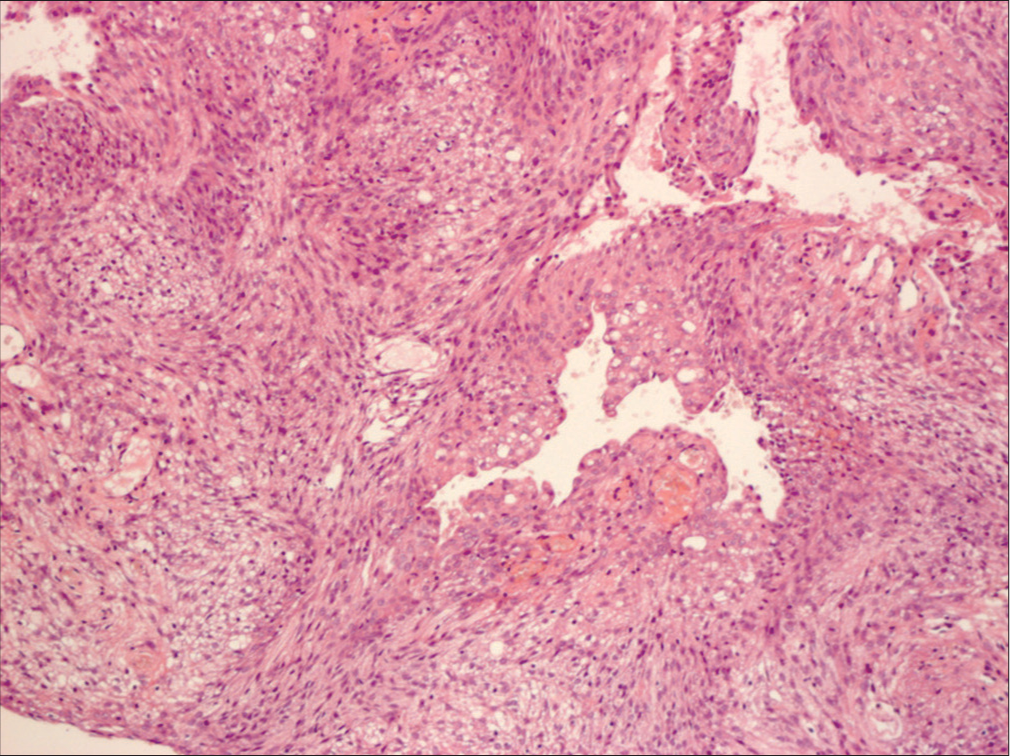

Meningiomas and gliomas are the two most common types of human intracranial tumors. However, meningiomas are not exclusively human tumors and are often seen in dogs and cats. In the treatment of dog meningiomas, there remains a lack of clarity about surgical treatment. Radiation, chemotherapy, and even stereotactic radiosurgery are often recommended while observation and euthanasia are viable options. Despite the same histological features as humans, dog meningiomas are always considered a malignant disease and treated as such.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

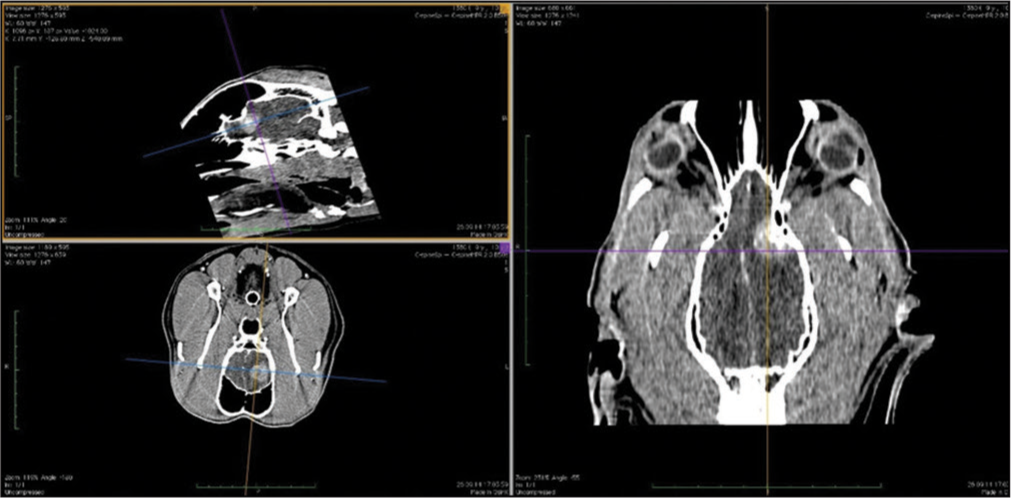

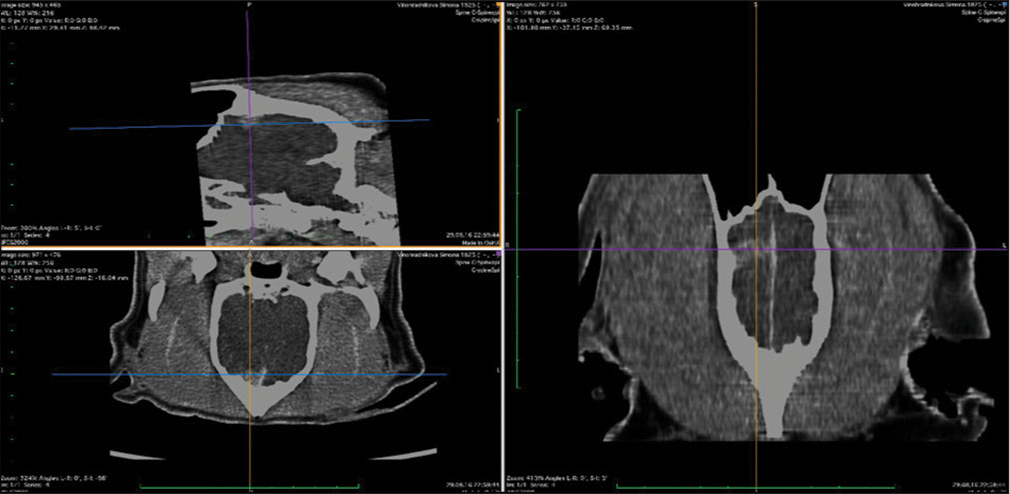

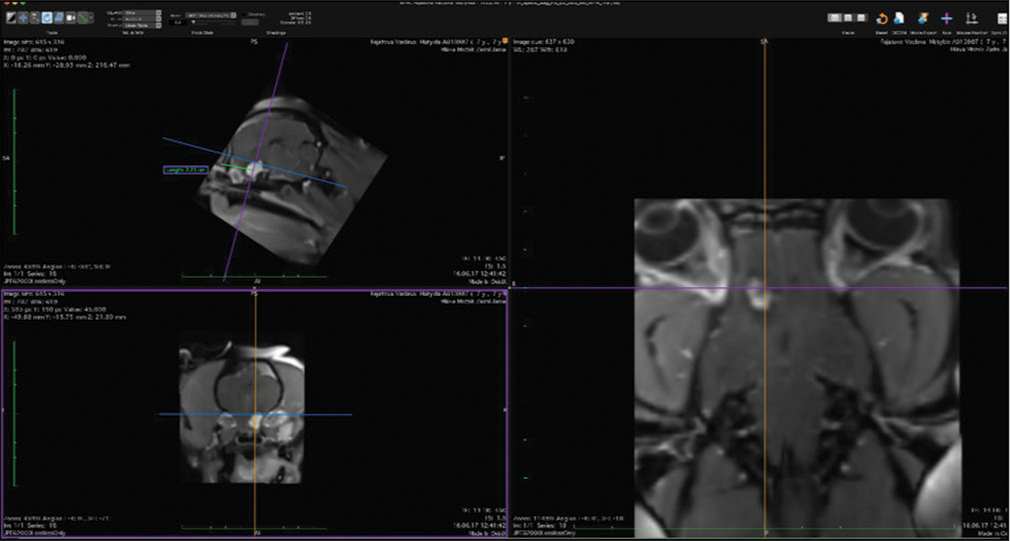

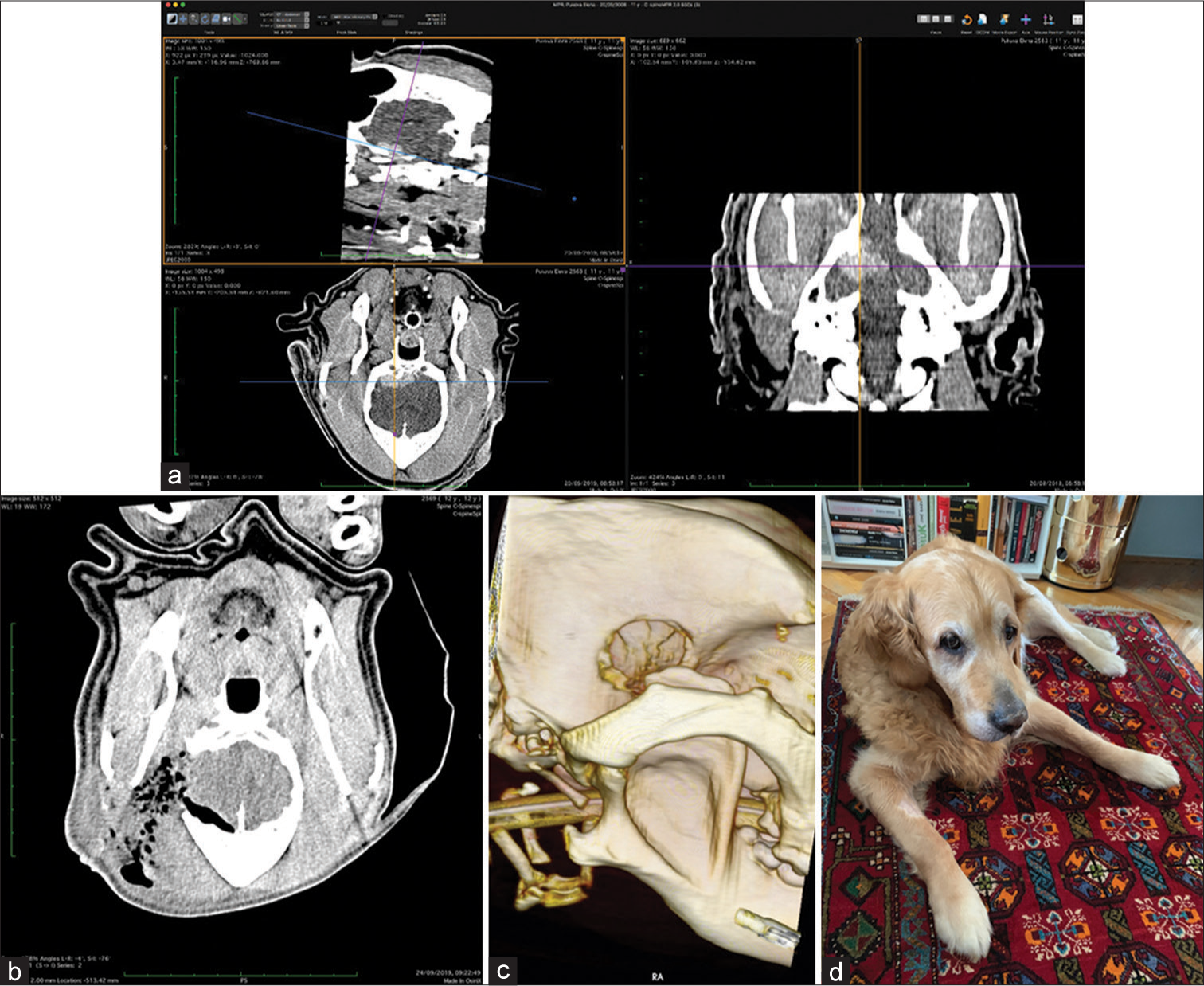

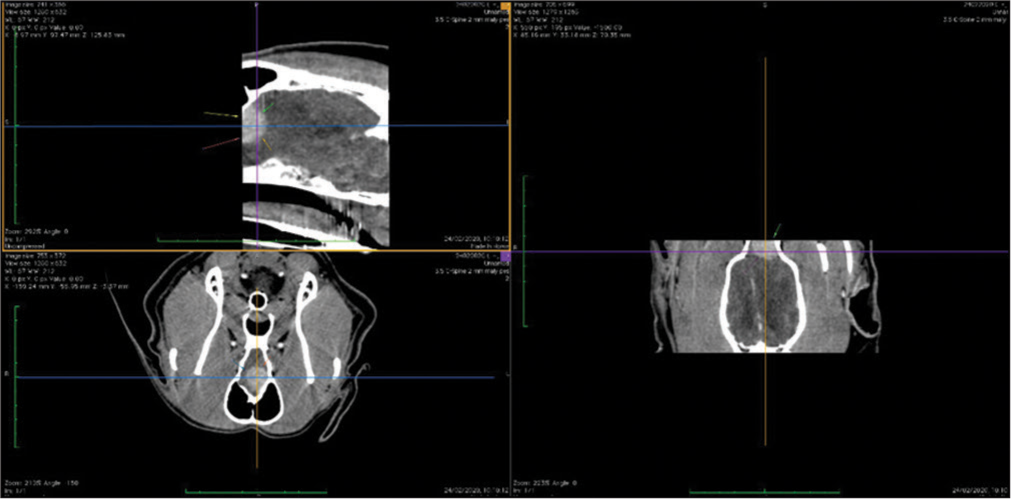

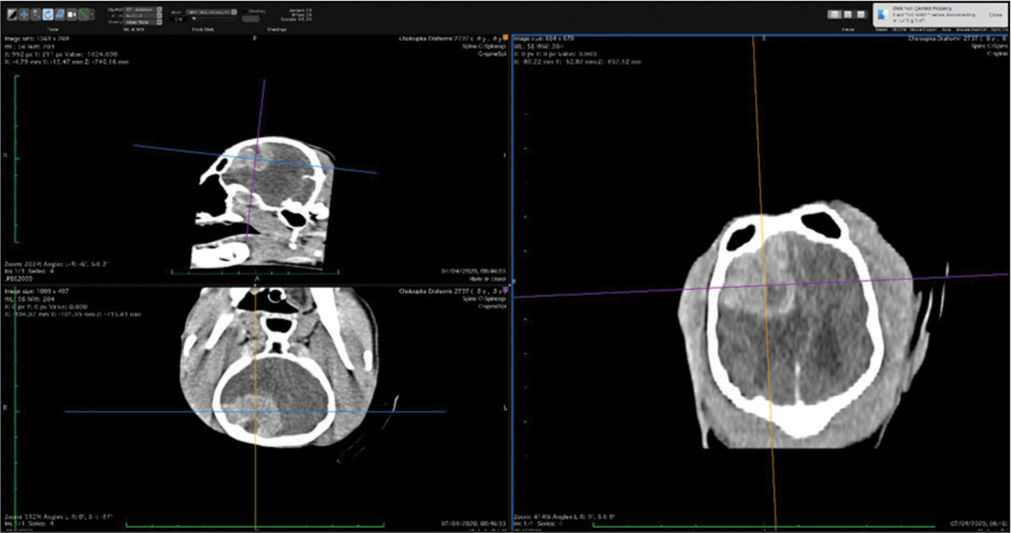

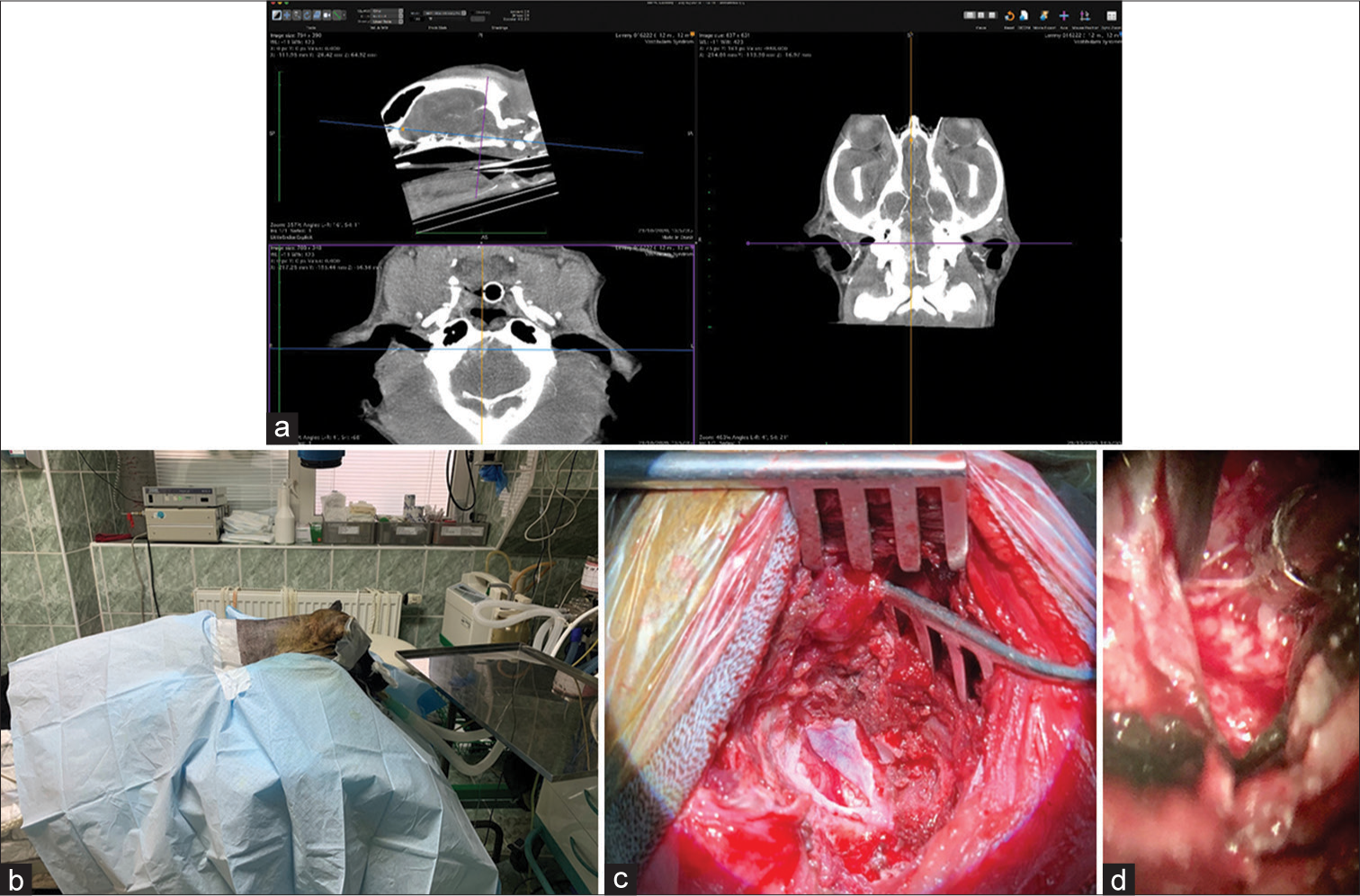

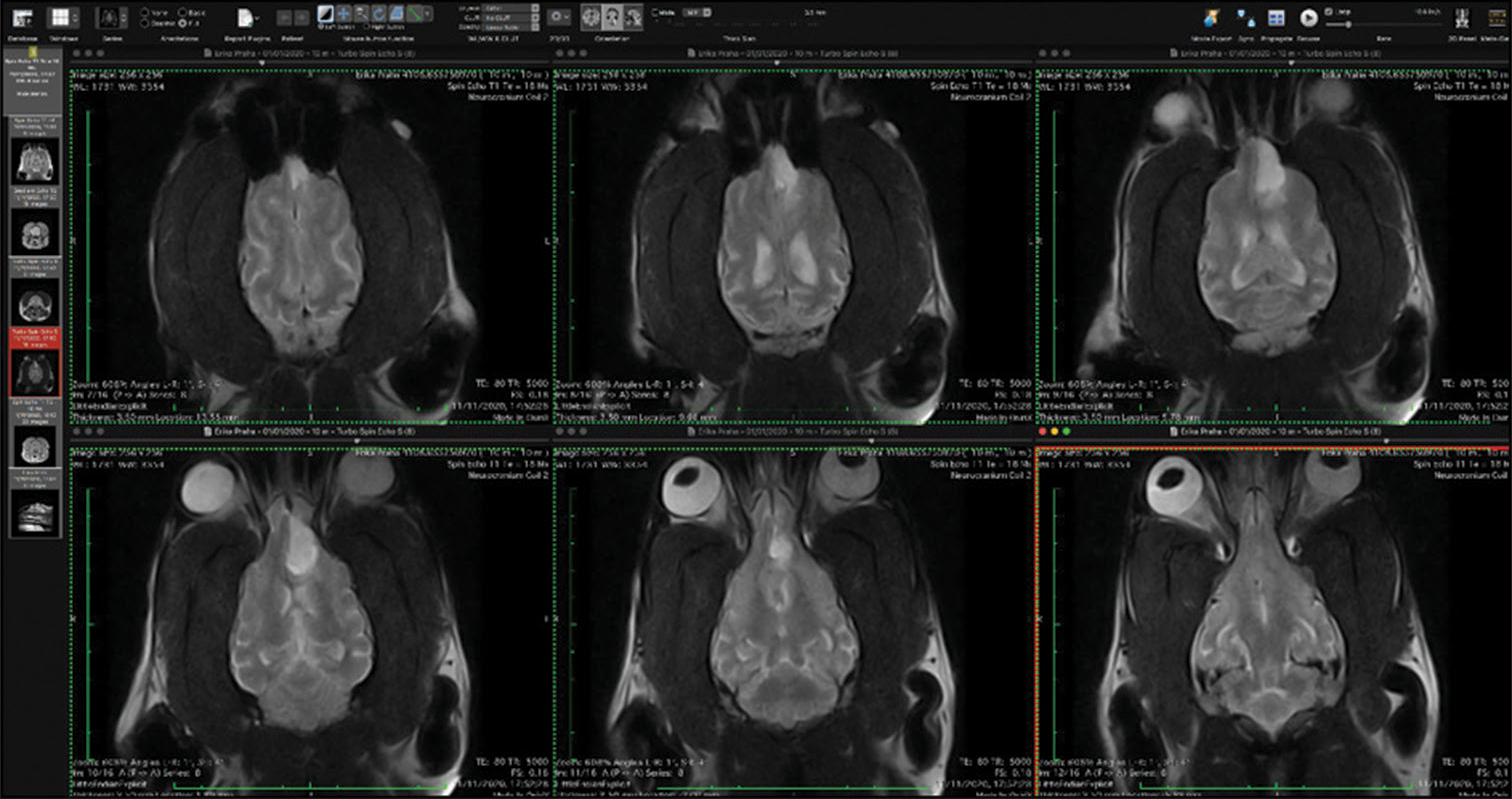

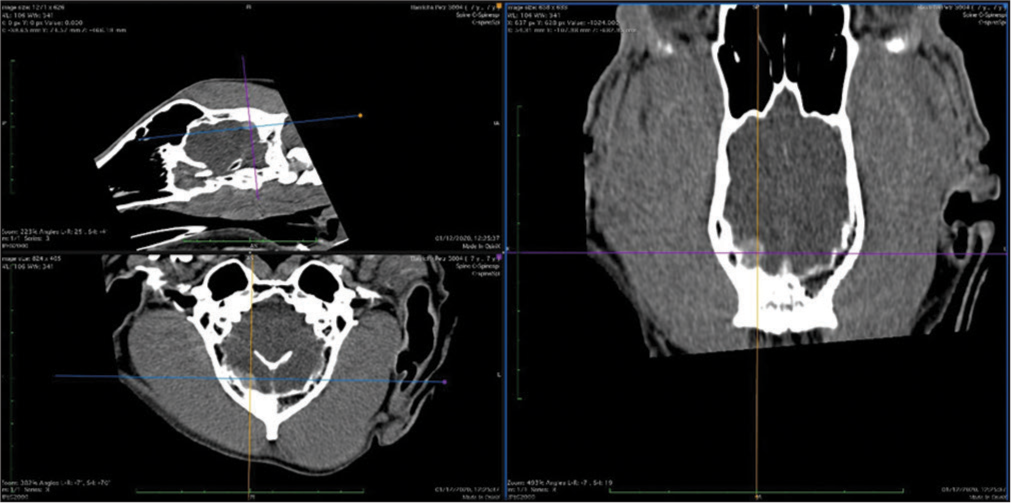

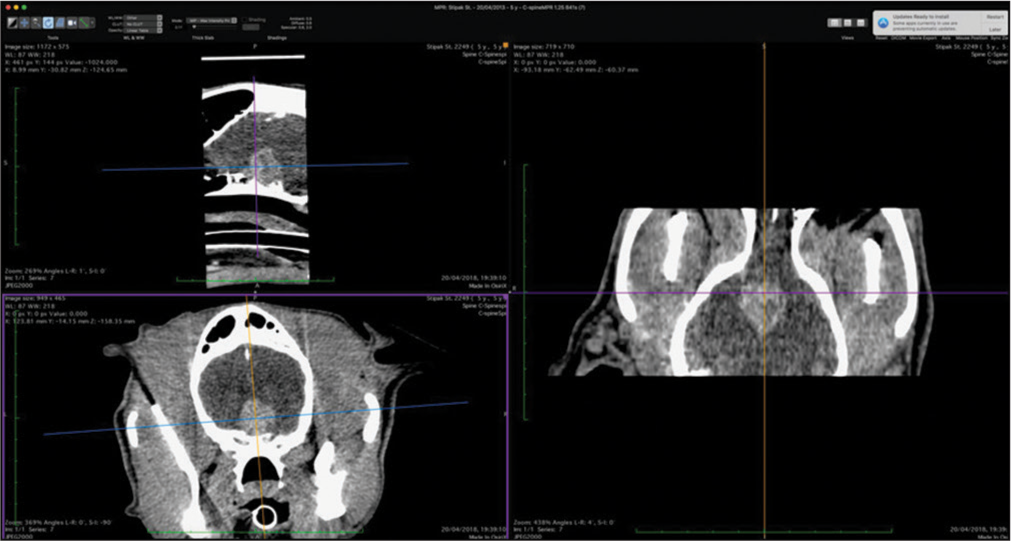

The veterinary clinic (owned by one of the authors of this paper, DV) operates its own computed tomography (CT) (Siemens Emotion Duo, Erlangen, Germany). Thus, the majority of diagnostic procedures were done by CT (9/11 cases). In only two dogs was magnetic resonance (MR) available (both were done elsewhere on Siemens Essenza, Erlangen, Germany). The clinic has a standard OR [

CT was the diagnostic procedure in nine cases; in the remaining two cases, the dogs came to our attention through MR, which was performed elsewhere. Postoperative imaging was performed in only one case. Because the owners are required to pay the full service, most did not opt for postoperative imaging.

RESULTS

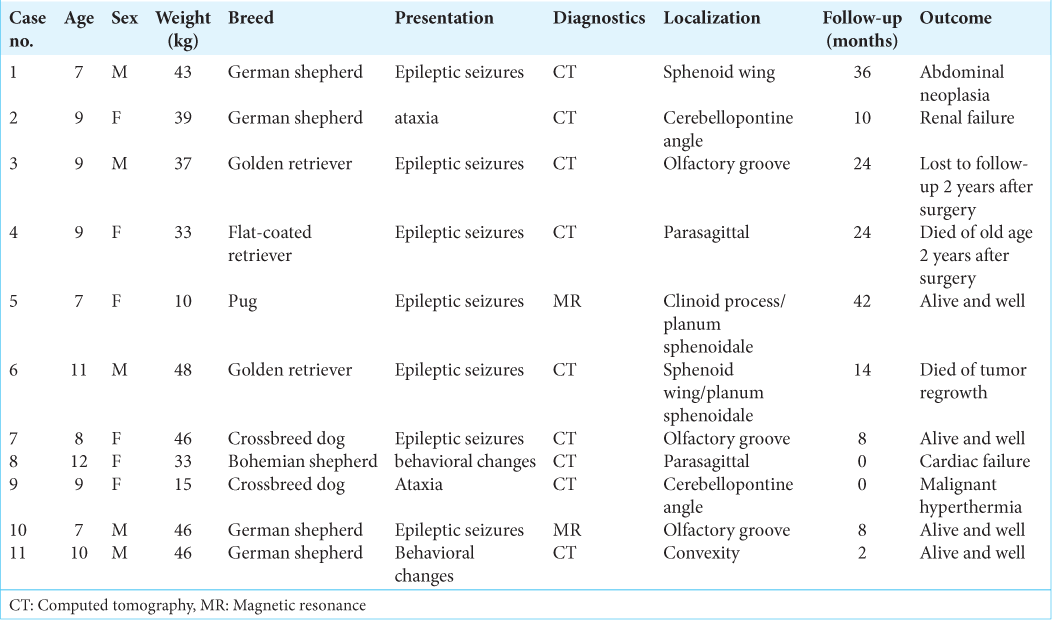

Basic data are given in [

Tumor location

In general, meningiomas of dogs can be found in the same location as human meningiomas. The sites are given in [

Surgery

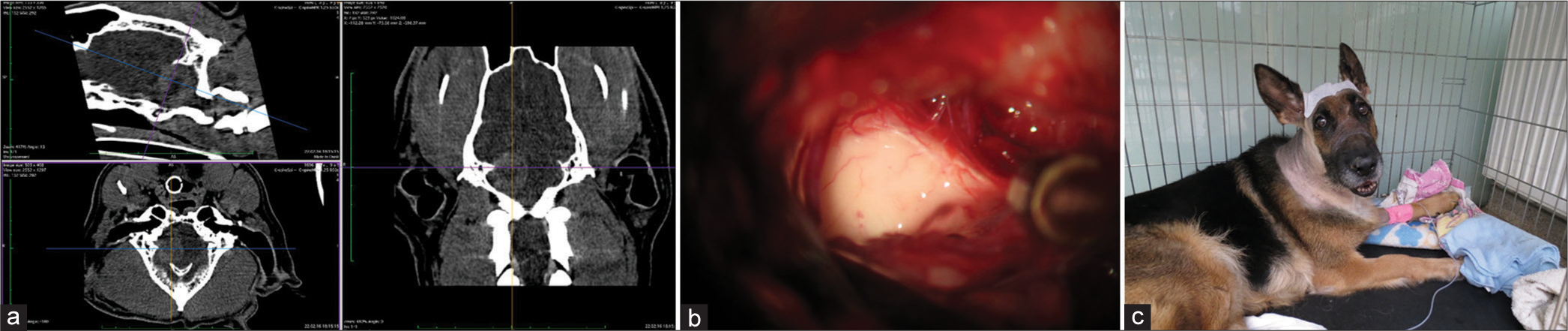

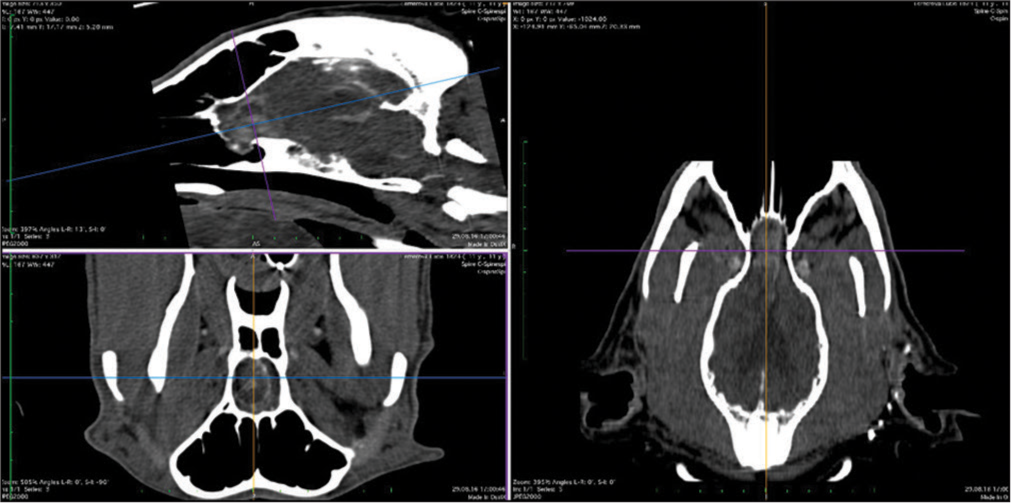

The skull and brain of dogs are smaller than those in humans. The location of tumors mirrors that of human tumors (see images) but the dog skull differs and the orientation is rather difficult. The approach is usually an intricate part of the surgery. In supratentorial tumors, the landmarks are midline, both orbits and bone crest between the supratentorial and infratentorial compartment. The frontal sinus is enormous, virtually covering most of the supratentorial compartment. The craniotomy is performed with a drill, where the first cut leads to the sinus and only the second is true craniotomy. Olfactory tumors are found quite easily between the orbits. The most frequent craniotomy in humans, the pterional, is somewhat different in dogs. The wing is very shallow and any millimeter miss leads to difficult orientation. The shallow and nearly flush anterior and middle cerebral fossae may lead the surgeon astray from the wing and tumor. Retracting the frontal lobe is difficult: the structures are small, where even a tiny artery of <1 mm diameter may be a major trunk. The craniotomy should always lead directly to the tumor, which is immediately apparent after opening the dura. We could resect one small clinoid tumor [

The posterior fossa is even more difficult. The occipital bone is at the right angle to the spine’s axis. It is usually overhung by the bone crest between the supra and infratentorial compartment where all the nuchal muscles are attached. The muscles need to be dissected free and the crest resected to gain good access to the CP angle. Except for the skin incision, whole surgery is performed under high magnification of the surgical microscope. The craniotomies are small, some 20–30 mm in diameter. The bone is not replaced, even when we entered the frontal sinus, where we encountered only one inflammatory complication.

The dura is nearly transparent and very delicate, especially in small dogs. It is opened in a regular fashion with the flap oriented towards the sinuses, which are carefully avoided. Again, the sinuses are not readily apparent and once injured the best defense to stop the bleeding is gentle tamponade with Surgicel. At the end of surgery, the dura is left opened and the DuraSeal covers the whole craniotomy.

In all but one case, we achieved radical Simpson 2 resection. We have experienced one postoperative wound infection necessitating drainage and antibiotic treatment. Two dogs died directly related to surgery: one was due to cardiac failure and the other to malignant hyperthermia (mortality 18%). Three dogs died of nonrelated causes at 10, 24, and 36 months after surgery. One died 1-year postsurgery due to a relapsing tumor. One dog was lost to follow-up at 24 months after surgery. Four dogs are alive and well 2, 8, 8, and 42 months after surgery [

DISCUSSION

In the veterinary literature, meningiomas are not the trending topic as in human neurosurgery. In a systematic meta-analysis, Hu et al.[

In our series, the median time that the dogs survived surgery was 18.7 months (range 2–42 months). Surgical mortality was 18%. Four dogs are alive and well 2, 8, 8, and 42 months after surgery. These results are similar to previously reported cases.[

Surgery for meningiomas is infrequent; the largest series we found in the literature was 39 cases (endoscopy assisted).[

The surgical technique for dogs does not differ much from meningioma surgery in humans and entails dissection with cottonoids, breaking the tumor and piecemeal resection. Most of the tumors are soft and hence suckable.[

We always tried to achieve Simpson 2 resection with the coagulation of the tumor origin (the concept of human neurosurgery was never mentioned in the veterinary reports). Veterinarians have published, for instance, more prolonged survival with the implementation of CUSA,[

Location-wise our tumors closely mirrored those of humans. We have seen olfactory, parasagittal, sphenoid wing, and cerebellopontine angle tumors. In the review of Motta et al.,[

In the veterinary literature, survival is prolonged by radiation and chemotherapy.[

Survival is not long considering human time perception. However, the equivalent of 1 year for a human is 7 for a dog, which is 1/12–1/15th of the animal’s life span. This information must be conveyed to the dog owners and they must be advised of alternatives (most probable would be euthanasia). The treatment cost also needs to be taken into account, as pets do not have health insurance. It might be worthwhile to speculate on the speed of growth in dog meningiomas. Do they grow proportionally faster than human meningiomas given that the life span of the dog is shorter or do they grow slower? The latter option does not seem plausible. Thus, the relapse of the disease or the growth of the remnant 1 year after the initial treatment seems a more reasonable outcome.

CONCLUSION

For a neurosurgeon with extensive experience with meningiomas, the dog meningiomas pose an “amusing challenge.” Given the size of the dog’s brain, it is a true form of microneurosurgery. The authors hope the article can lighten up the mood from the technical and heavy science literature we usually encounter in our medical journals and that it will fall in with the perpetual and insatiable curiosity inherent in those professionals working in the field of neurosurgery.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient‘s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

AZV grant NV19-04-00272.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Axlund TW, McGlasson ML, Smith AN. Surgery alone or in combination with radiation therapy for treatment of intracranial meningiomas in dogs: 31 cases (1989-2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002. 221: 1597-600

2. Barreau P, Dunn K, Fourie Y. Canine meningioma: A case report of a rare subtype and novel atlanto basioccipital surgical approach. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2010. 23: 372-6

3. Greco JJ, Aiken SA, Berg JM, Monette S, Bergman PJ. Evaluation of intracranial meningioma resection with a surgical aspirator in dogs: 17 Cases (1996-2004). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006. 229: 394-400

4. Heidner GL, Kornegay JN, Page RL, Dodge RK, Thrall DE. Analysis of survival in a retrospective study of 86 dogs with brain tumors. J Vet Intern Med. 1991. 5: 219-26

5. Hu H, Barker A, Harcourt-Brown T, Jeffery N. Systematic review of brain tumor treatment in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2015. 29: 1456-63

6. Ijiri A, Yoshiki K, Tsuboi S, Shimazaki H, Akiyoshi H, Nakade T. Surgical resection of twenty-three cases of brain meningioma. J Vet Med Sci. 2014. 76: 331-8

7. Klopp LS, Rao S. Endoscopic-assisted intracranial tumor removal in dogs and cats: Long-term outcome of 39 cases. J Vet Intern Med. 2009. 23: 108-15

8. Magalhaes TR, Benoit J, Necova S, North S, Queiroga FL. Outcome after radiation therapy in canine intracranial meningiomas or gliomas. In Vivo. 2021. 35: 1117-23

9. Moreau JJ, Moreau P, Vallat JM, Desnoyers P, Leboutet MJ, Pascaud JL. Surgical excision of meningioma of the posterior fossa in a dog after detection by x-ray computed tomography. Neurochirurgie. 1986. 32: 523-8

10. Motta L, Mandara MT, Skerritt GC. Canine and feline intracranial meningiomas: An updated review. Vet J. 2012. 192: 153-65

11. Niebauer GW, Dayrell-Hart BL, Speciale J. Evaluation of craniotomy in dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991. 198: 89-95

12. Sunol A, Mascort J, Font C, Bastante AR, Pumarola M, FeliuPascual AL. Long-term follow-up of surgical resection alone for primary intracranial rostrotentorial tumors in dogs: 29 Cases (2002-2013). Open Vet J. 2017. 7: 375-83