- Department of Anesthesia, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_461_2019

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: R. Sriharsha, Ketan K. Kataria, Shyam Meena, Kiran Jangra, Summit Bloria. Postoperative cardiorespiratory arrest in a case of cervical meningocele. 13-Mar-2020;11:45

How to cite this URL: R. Sriharsha, Ketan K. Kataria, Shyam Meena, Kiran Jangra, Summit Bloria. Postoperative cardiorespiratory arrest in a case of cervical meningocele. 13-Mar-2020;11:45. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=9912

Abstract

Background: Meningoceles are congenital herniation of meninges and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through the skull and are bereft of any cerebral tissue. They are commonly found over the anterior fontanelle. Although some cases of cervical dysraphism have been described in the literature, a true meningocele has rarely been seen. The child usually presents with hydrocephalus with features of raised increased intracranial pressure. Sensory, motor, and sphincter functions may be involved depending on the level of lesion. Closure of meningocele should be ideally done within the first 48 h of birth.

Case Description: Complications associated with meningocele range from learning disabilities, seizures, and bowel dysfunction to complete paralysis below the level of the lesion. The postoperative complications reported are wound infection, CSF leak/collection, urinary tract infection, deterioration of deficit, and death. Here, we present a postoperative case of an 11-month-old child with cervical meningocele who had an unusual complication almost 2 h after an uneventful surgery in the form of sudden cardiorespiratory arrest was revived successfully.

Conclusion: A meningocele surgery is usually not associated with severe postoperative complications which can be encountered in meningomyelocele surgery. Here, in our case, the child with uneventful meningocele surgery arrested 2 h postsurgery with the possible cause being cervical cord edema. Hence, a lesson was learned that strict vigilance is also required in postoperative care for meningocele patients.

Keywords: Cardiorespiratory arrest, Cervical meningocele, Hydrocephalus

BACKGROUND

Spina bifida cystica preferentially affects the lower regions of the spine and is rarely seen in the cervical region. They have been published as isolated case reports in the literature and very little is known about the postoperative complications. Clinical presentation of meningocele is usually a soft cervical mass without marked neurological impairment at the time of diagnosis. External features of the cervical lesion are tubular protuberances at the back of neck covered at the base and most of the cylindrical wall by full-thickness skin and on the dome by thick squamous epithelium.

CASE REPORT

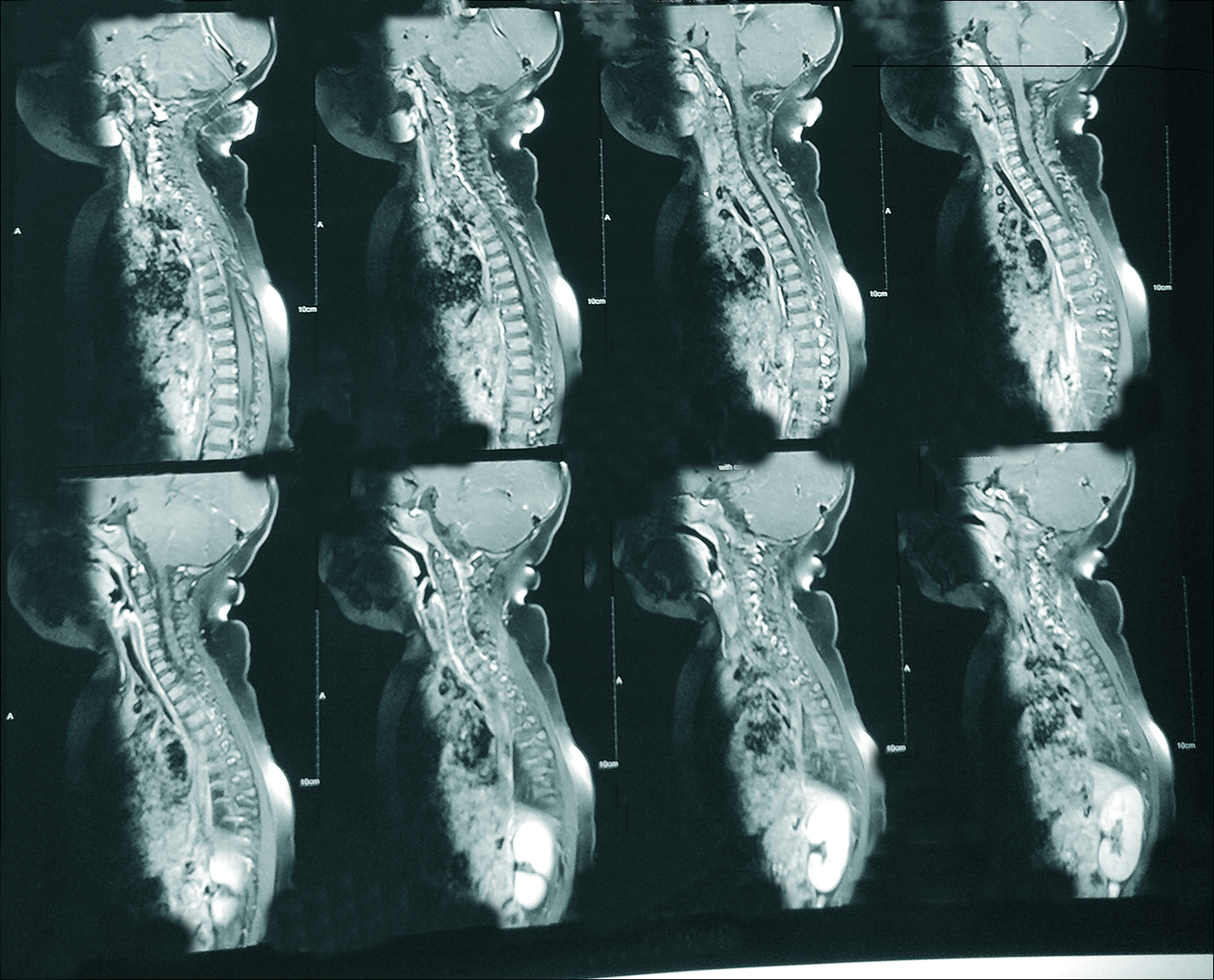

An 11-month-old male child was posted for cervical meningocele excision of redundant sac with simple skin closure in the neurosurgery operation theater (OT) of our institute. The patient had come with the complaints of soft swelling of around 3 cm × 3 cm over the nape of the neck since birth which was expansile in nature. There were no other complaints, the patient’s neurological examination was unremarkable and the patient was neurologically intact. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain + whole spine of the patient showed the meningocele at C2C3 region [

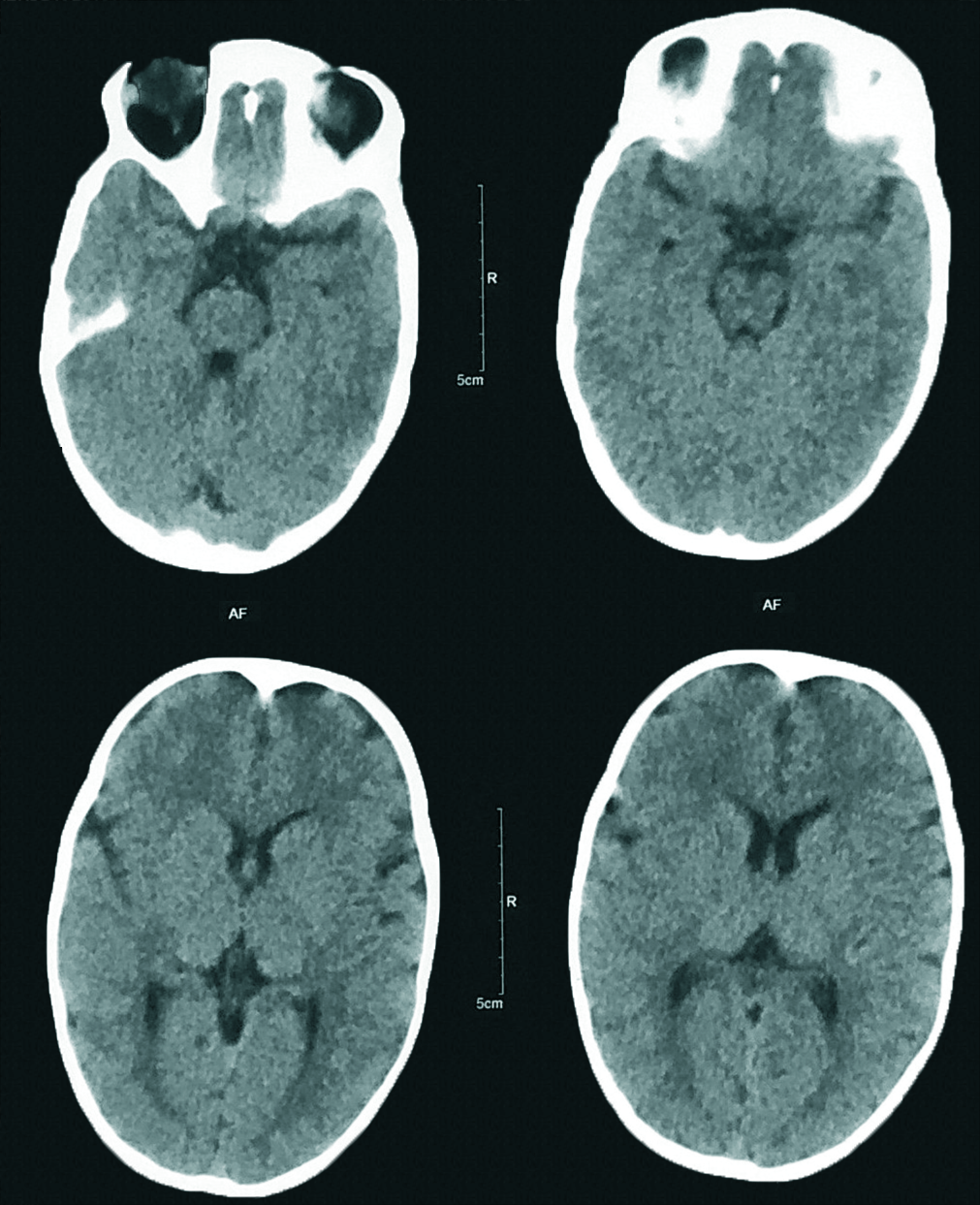

The patient was conscious and responding. Supplementary oxygen was provided through Ventimask. On arrival, the patient’s heart rate was 110 beats/min, SpO2 was 100%, the blood pressure was 90/46 mmHg, and the shifting EtCO2 was 37 mmHg. At around 12:30 pm, the patient developed sudden tachycardia of around 205 beats/min followed by bradycardia with fall of heart rate up to 30 beats/min within few seconds followed by asystole. The patient became unresponsive at the same time. Cardio pulmonary cerebral resuscitation (CPCR) was initiated immediately with chest compressions and bag and mask ventilation. Inj. adrenaline 100 µg bolus was given. The patient was revived after one cycle of CPCR. The patient was intubated, ventilated and was shifted for a computed tomography (CT) brain. The CT brain did not show any significant findings [

DISCUSSION

Spinal dysraphism is an uncommon condition reported in 30-40/100,000 live births.[

Meningocele is usually a soft cervical mass without marked neurological impairment at the time of diagnosis. External features of the cervical lesion are tubular protuberances at the back of neck covered at the base and most of the cylindrical wall by full-thickness skin and on the dome by thick squamous epithelium. It is recognized as a sac, which contains cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), neuroglial or fibrous tissue, formed as a result of herniation of the dura structure of the spinal midline defect, while myelomeningocele is recognized as a central sac, which contains neuroglial structures or a meningocele with a medulla spinalis.[

After resuscitation and stabilization, an arterial blood gas was done which did not show any electrolyte abnormalities, so the differential of electrolyte abnormality was ruled out. The patient was then immediately wheeled in for a CT brain with spine, which did not show any signs of hydrocephalus, raised intracranial pressure, brain stem herniation, or surgical site bleed, so these possibilities as a cause of deterioration were also ruled out. The possibility of inadequate reversal was very unlikely as the patient deteriorated after almost 2 h and the TOF was 90% on shifting to PACU. The differential of ATCCS looked unlikely as there was no hyperextension done at any time during surgery and there was no inciting trauma as well. Hence, the most probable diagnosis of cervical cord edema was made after ruling out other probable differentials. The possibility of a cervical cord handling was also put to question as after discussing with the neurosurgeon, we were assured that there was no spinal cord handling intraoperatively which could have been the case if it was a meningomyelocele. Hence, the definitive diagnosis of cardiac arrest is unclear, especially as it was within hours of surgery and anesthesia delivery. There is very scarce literature available regarding the postoperative complications associated with meningocele. We failed to find any report of a similar incident in the literature. Usually in a meningocele surgery, we do not expect any postoperative complications as in the case with meningomyelocele where there are various complications that can happen which have been mentioned above. Hence, one usually fails to anticipate the possible severe complications that can take place even in the case of meningocele. This case was an eye-opener for the fraternity at our institute regarding the standard operating procedures to be followed even in a case of a relatively uncomplicated meningocele surgery.

CONCLUSION

A meningocele surgery, i.e. excision of redundant sac with simple skin closure is usually not associated with severe postoperative complications which can be encountered in meningomyelocele surgery. Here, in our case, the child with uneventful meningocele surgery arrested 2 h postsurgery with the possible cause being cervical cord edema. Hence, a lesson was learned that strict vigilance is also required in postoperative care for meningocele patients.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Andronikou S, Wieselthaler N, Fieggen AG. Cervical spina bifida cystica: MRI differentiation of the subtypes in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006. 22: 379-84

2. Huang SL, Shi W, Zhang LG. Characteristics and surgery of cervical myelomeningocele. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010. 26: 87-91

3. Kasliwal MK, Dwarakanath S, Mahapatra AK. Cervical meningomyelocele--an institutional experience. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007. 23: 1291-3

4. Kıymaz N, Yılmaz N, Güdü BO, Demir I, Kozan A. Cervical spinal dysraphism. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2010. 46: 351-6

5. Mahapatra AK. Spinal dysraphism controversies: AIIMS experiences and contribution. Indian J Neurosurg. 2012. 1: 4-8

6. Pang D, Dias MS. Cervical myelomeningoceles. Neurosurgery. 1993. 33: 363-72

7. Pessoa BL, Lima Y, Orsini M. True cervicothoracic meningocele: A rare and benign condition. Neurol Int. 2015. 7: 6079-

8. Rossi A, Piatelli G, Gandolfo C, Pavanello M, Hoffmann C, Van Goethem JW. Spectrum of nonterminal myelocystoceles. Neurosurgery. 2006. 58: 509-15

9. Tortori-Donati P, Rossi A, Biancheri R, Cama A. Magnetic resonance imaging of spinal dysraphism. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2001. 12: 375-409