- Department of Neurosurgery, Kagoshima University, Sakuragaoka, Kagoshima, Japan

- Department of Neurologic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States.

- Department of Radiology, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Kagoshima University, Sakuragaoka, Kagoshima, Japan,

Correspondence Address:

Kazunori Arita

Department of Neurosurgery, Kagoshima University, Sakuragaoka, Kagoshima, Japan

DOI:10.25259/SNI_5_2020

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Kazunori Arita, Makiko Miwa, Manoj Bohara, FM Moinuddin, Kiyohisa Kamimura, Koji Yoshimoto. Precision of preoperative diagnosis in patients with brain tumor – A prospective study based on “top three list” of differential diagnosis for 1061 patients. 28-Mar-2020;11:55

How to cite this URL: Kazunori Arita, Makiko Miwa, Manoj Bohara, FM Moinuddin, Kiyohisa Kamimura, Koji Yoshimoto. Precision of preoperative diagnosis in patients with brain tumor – A prospective study based on “top three list” of differential diagnosis for 1061 patients. 28-Mar-2020;11:55. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/9929/

Abstract

Background: Accurate diagnosis of brain tumor is crucial for adequate surgical strategy. Our institution follows a comprehensive preoperative evaluation based on clinical and imaging information.

Methods: To assess the precision of preoperative diagnosis, we compared the “top three list” of differential diagnosis (the first, second, and third diagnoses according to the WHO 2007 classification including grading) of 1061 brain tumors, prospectively and consecutively registered in preoperative case conferences from 2010 to the end of 2017, with postoperative pathology reports.

Results: The correct diagnosis rate (sensitivity) of the first diagnosis was 75.8% in total. The sensitivity of the first diagnosis was high (84–94%) in hypothalamic-pituitary and extra-axial tumors, 67–75% in intra-axial tumors, and relatively low (29–42%) in intraventricular and pineal region tumors. Among major three intra-axial tumors, the sensitivity was highest in brain metastasis: 83.8% followed by malignant lymphoma: 81.4% and glioblastoma multiforme: 73.1%. Sensitivity was generally low (≦60%) in other gliomas. These sensitivities generally improved when the second and third diagnoses were included; 86.3% in total. Positive predictive value (PPV) was 76.9% in total. All the three preoperative diagnoses were incorrect in 3.4% (36/1061) of cases even when broader brain tumor classification was applied.

Conclusion: Our institutional experience on precision of preoperative diagnosis appeared around 75% of sensitivity and PPV for brain tumor. Sensitivity improved by 10% when the second and third diagnoses were included. Neurosurgeons should be aware of these features of precision in preoperative differential diagnosis of a brain tumor for better surgical strategy and to adequately inform the patients.

Keywords: Brain tumor, Positive predictive value, Precision, Preoperative differential diagnosis, Sensitivity

INTRODUCTION

The precision of preoperative diagnosis of brain tumor is crucial for deciding the pertinent operative strategy and for providing adequate information to the patient. We, neurosurgical team, generally apply a preoperative differential diagnosis for the brain tumors based on clinical and image information in the preoperative case conference. In spite of several reports on the precision of preoperative neuroimaging diagnosis of brain tumor,[

Although only one preoperative probable diagnosis is usually sufficient in most cases of brain tumor, we occasionally come across cases requiring the change of surgical strategy intraoperatively due to the incorrect preoperative diagnosis. Therefore, we have prospectively and consecutively registered “top three list” of differential diagnoses at the end of the preoperative discussion for each case of brain tumor since 2010. Based on the list, we have made surgical strategy. We here compared the “top three list” with postoperative pathology lists in 1061 brain tumors treated from 2010 to the end of 2017 to evaluate the precision of preoperative diagnosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The subjects were 584 women and 477 men with initial brain tumor operated on, from January 2010 to December 2017, in which registration of “top three list” of differential diagnoses was given and postoperative pathological diagnosis was determined. Median and mean ages were 60 (ranging from 0 to 89) and 55.8 ± 18.7 (SD) years, respectively.

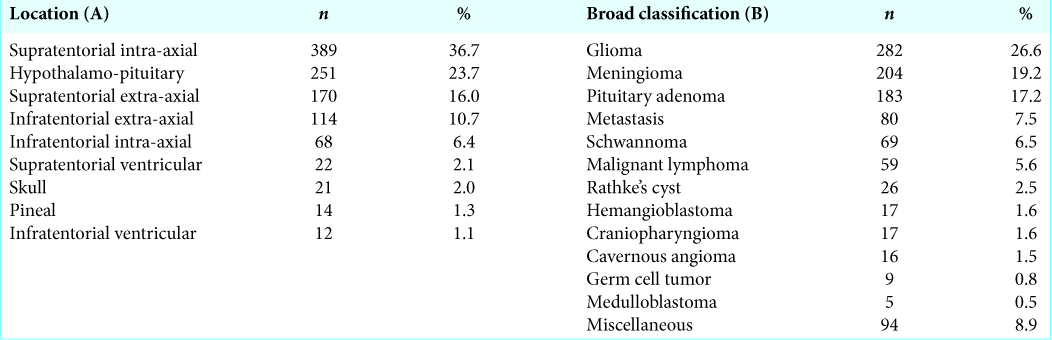

The location of the tumor was suprasellar intra-axial in 389 (36.7%), hypothalamo-pituitary in 251 (23.7%), supratentorial extra-axial in 170 (16.0%), infratentorial extra-axial in 114 (10.7%), infratentorial intra-axial in 68 (6.4%), supratentorial ventricular in 22 (2.1%), skull in 21 (2.0%), pineal in 14 (1.3%), and infratentorial ventricular in 12 (1.1%) [

The broad classification of the tumor was glioma in 282 (26.6%), meningioma in 204 (19.2%), pituitary adenoma in 183 (17.2%), metastasis in 80 (7.5%), schwannoma in 69 (6.5%), malignant lymphoma in 59 (5.6%), Rathke’s cleft cyst in 26 (2.5%), hemangioblastoma in 17 (1.6%), craniopharyngioma in 17 (1.6%), cavernous angioma in 16 (1.5%), germ cell tumor in 9 (0.8), medulloblastoma in 5 (0.5%), and miscellaneous in 94 (8.9%) patients [

Neuroimaging

Plain three axes preoperative computed tomographic (CT) images were in all obtained using Aquilion 64 Rows Multislice CT or Aquilion ONE 320 Rows Multislice CT (Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan). Magnetic resonance images (MRIs) were obtained except for 9 (0.8%) patients with a pacemaker, using 3T Ingenia (Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands), 3T Trio (Siemens, Malvern, PA, USA), 1.5T Magnetom Vision (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), or Aera (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The basic imaging sequences for MRI were T1-weighted image (with slice thickness [ST]: 5 mm), T2-weighted image (ST: 5 mm), fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (ST: 5 mm), and diffusion-weighted image (ST: 5 mm). Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images (ST: 5 mm) were obtained except for 25 (2.4%) patients with chronic renal failure. Gadolinium-enhanced 3D T1-weighted images (ST: 2 mm) were added in one-third of cases. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) data were obtained for all intra-axial tumors. Arterial spin labeling (ASL) image was obtained in recent 3 years (2015–2017) for intra-axial tumors. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography and methionine studies were done for suspected glioma and malignant lymphoma.

Top three list

Preoperative conference based on clinical and neuroimaging information including neuroradiology report was usually conducted a week before surgery. Clinical information included demographic characteristic, neurological presentation, tumor marker, clinical history, and other relevant histories. Attendees of the conference were board-certified neurosurgeons (8–12 persons) and neurosurgery residents (2–6 persons). On half of the occasions, diagnostic neuroradiology specialists (1–3 persons) attended. At the end of preoperative case discussion, one of the categories chosen from the WHO 2007 classification of tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) was registered as the most probable preoperative diagnosis, for example, anaplastic astrocytoma (Grade 3), atypical meningioma (Grade 2), or pineocytoma (Grade 1). Then, the second and third probable categories of the tumor were registered. For example, a supratentorial extra- axial tumor may be registered with meningioma Grade 2 as the first, meningioma Grade 1 as the second, and solitary fibrous tumor as the third differential diagnosis in the “top three list” for differential diagnosis. Rathke’s cleft cyst, not listed in the WHO classification as it is nonneoplastic, was included in the diagnostic categories. The discontent among the attendees was further discussed to reach an agreement. If it failed, in around 5% of cases, we voted to select the diagnosis from several candidates for differential diagnosis.

The surgery was performed under the first diagnosis with heed to the following two diagnoses. For example, when the first diagnosis was glioblastoma and the second diagnosis was malignant lymphoma, the craniotomy was done for maximum safe removal, but biopsy specimen was obtained at earliest opportunity. When the preoperative diagnosis was glioma, we routinely utilized intraoperative navigation and intraoperative MRI to pursue the utmost safe removal. All the specimens acquired during surgery were submitted to pathology; the higher WHO grade pathological diagnosis was adopted as the final diagnosis when the histological features differed from place to place.

Postoperative pathology report and comparison with “top three list”

Two pathologists made a diagnosis according to the WHO categorization of CNS tumors 2007 using histological specimens stained by hematoxylin and eosin and immunohistochemical staining for related proteins. Discordance between the pathologists was further discussed in the pathology conference and the final diagnosis was endorsed by the chief of the department of pathology. In cases with low-grade glioma, information on heterozygosity at 1p and 19q was added for the differentiation between astrocytic and oligodendroglial lineage. There were 9 (0.85%) among total 1061 tumors, in which the definite pathological diagnosis was not determined even through these steps. We got the final diagnosis of these 9 cases by sending the tumor tissue to Japan Brain Tumor Reference Center,

The “top three list” of the 1061 initial intracranial tumors was compared with the pathology reports by a coauthor (M.M.), nonattendees of neurosurgery or pathology conferences.

Statistical analysis

Calculation of values on preoperative diagnosis and statistical analyses was performed using StatFlex version 6.0 (Artech Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and OpenEpi (

Ethical consideration

This noninterventional study was endorsed by the Medical Ethics Committee of Kagoshima University Hospital (reference No. 180119, epidemiology research). The authors certify that this study involving human subjects was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2000 and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects (effective February 9, 2015) promulgated by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan. Informed consent for the treatment and for the use of their data in general research on brain tumor was obtained from all patients. The study-specific informed consent was waived due to the noninvasive nature of our study. An opt-out approach was offered to all patients. To protect patient privacy, all data were collected and analyzed under anonymization in an unlinkable fashion.

RESULTS

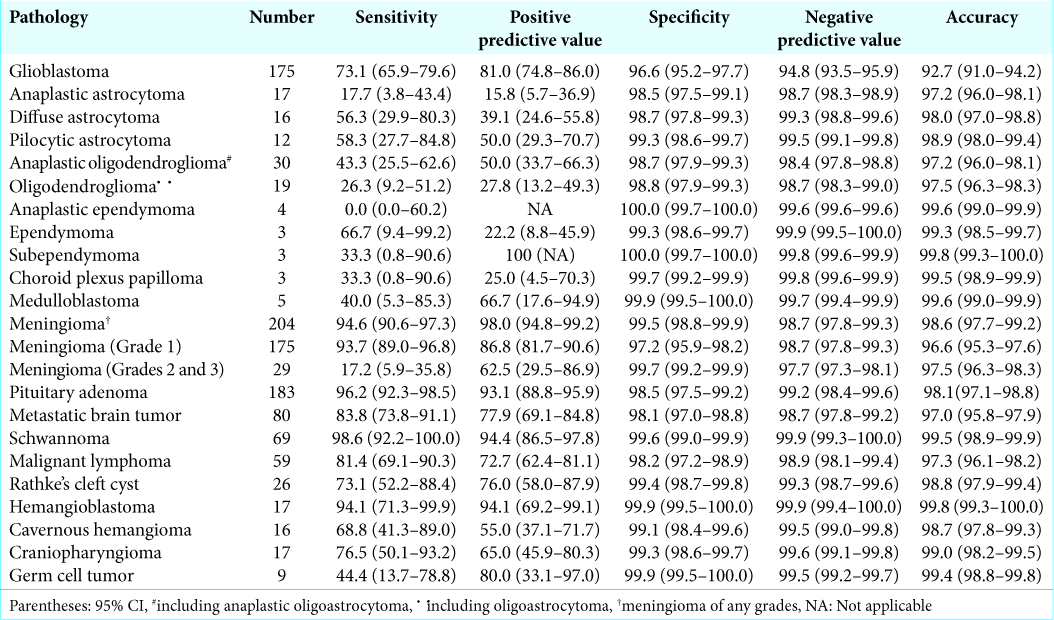

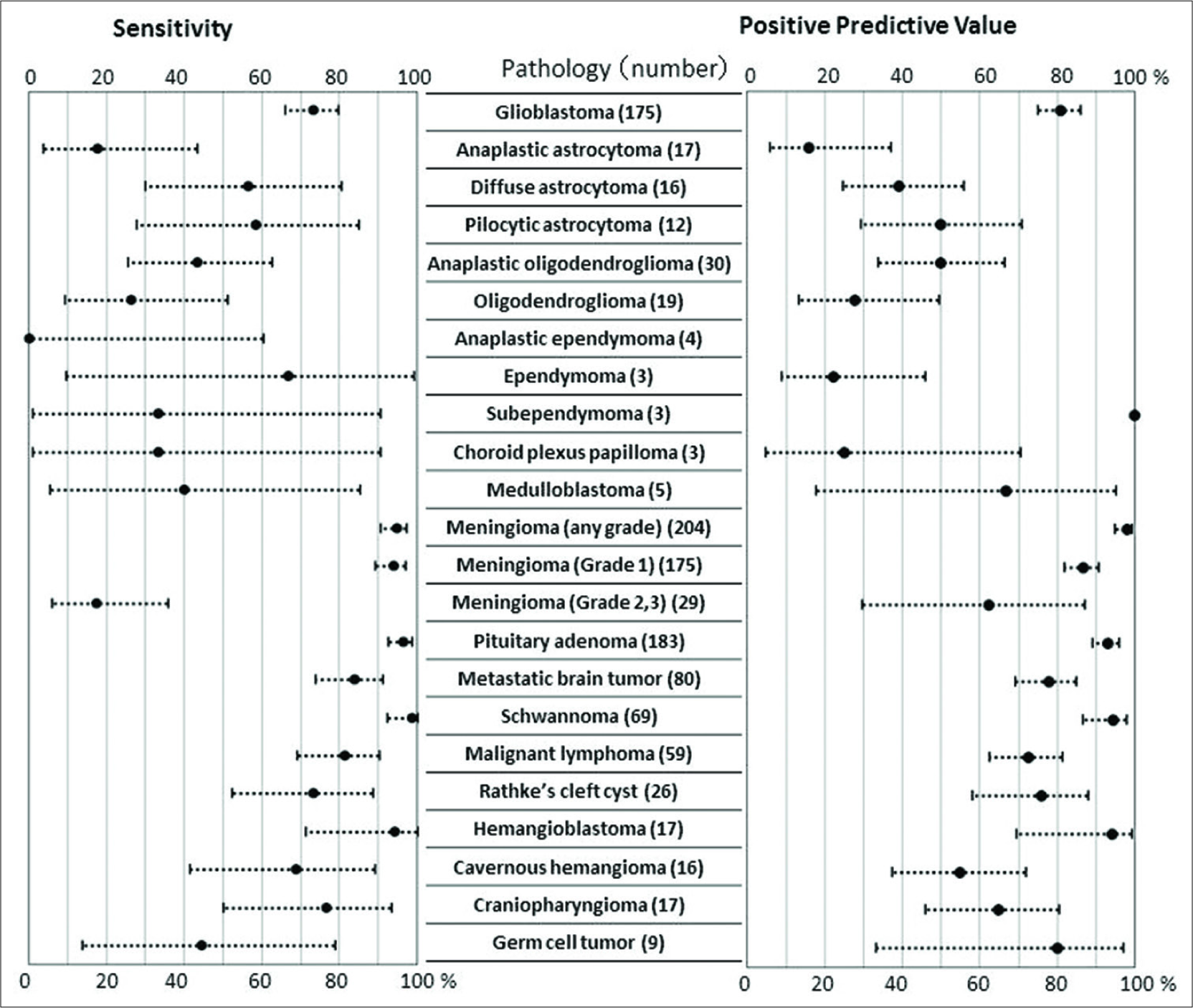

The statistical values of the preoperative diagnoses on major 23 kinds of brain tumor, which involved more than 4 patients, are presented in

Sensitivity in total

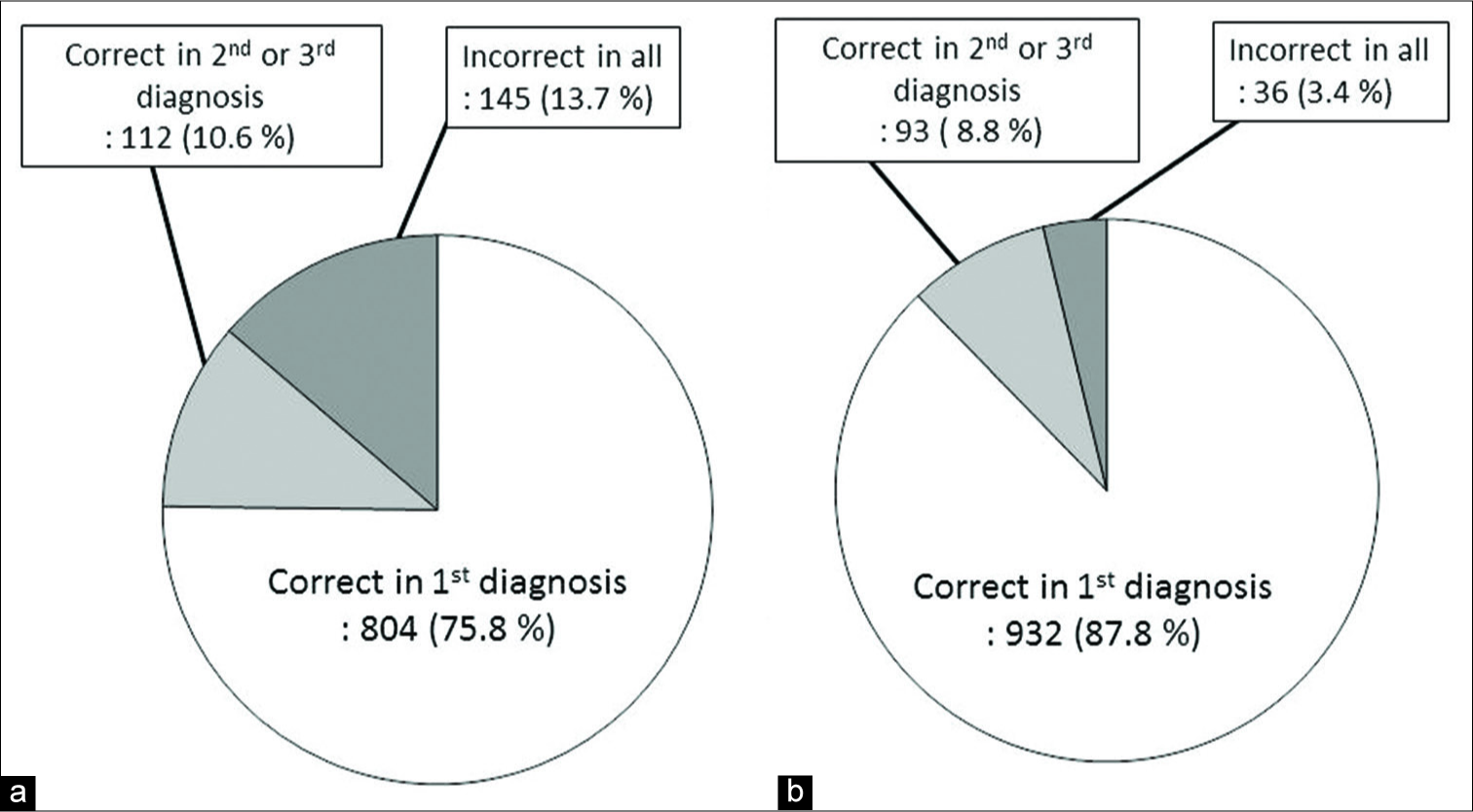

When the WHO classification and grading of the first preoperative differential diagnosis matched those of pathology reports, the preoperative differential diagnosis was judged to be correct. The correct diagnosis rate (sensitivity) of the first diagnosis for all 1061 tumors was 75.8% (95% confidence interval, CI: 73.1–78.3). The sensitivity significantly improved to 86.3% (95% CI: 84.1–88.3) when the second and third differential diagnoses were included (P < 0.0001, Chi-squared test) [

When the broader categorization was permitted, for example, preoperative diagnosis of meningioma (Grade 1) was permitted for a pathologically proven atypical meningioma (Grade 2), the sensitivity of the first diagnosis was 87.8% (95% CI: 85.7–89.8). It significantly improved to 96.6% (95% CI: 95.3–97.6) when the second and third diagnoses were included (P < 0.0001, Chi-squared test).

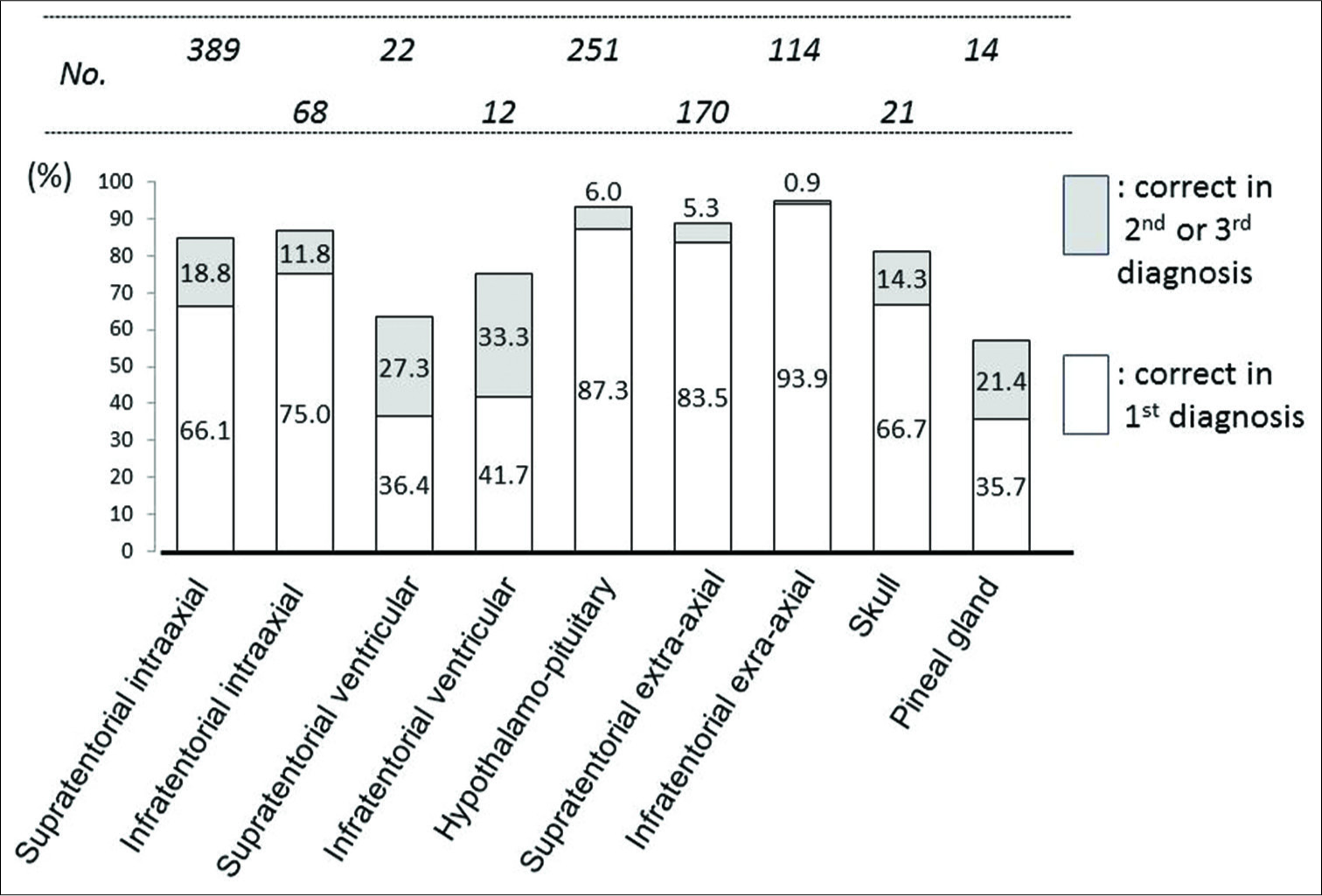

Sensitivity according to the location of the tumor

The sensitivity of the first differential diagnosis was high (>84%) in hypothalamic-pituitary, supratentorial extra-axial, and infratentorial extra-axial tumors. While it was low (36–42%) in supratentorial intraventricular, infratentorial intraventricular, and pineal region tumors; even with inclusion of the second and third diagnoses, the sensitivities were still <80% [

Sensitivity according to age groups

The sensitivity was significantly lower in 46 children (<18 years old) than in 1015 adults (≥18); 60.9% versus 76.5%, P = 0.0158. It was also significantly lower in children compared to two other age groups, 18–64 years and >64 years old; 60.9% versus 75.3% versus 78.2, P = 0.0312.

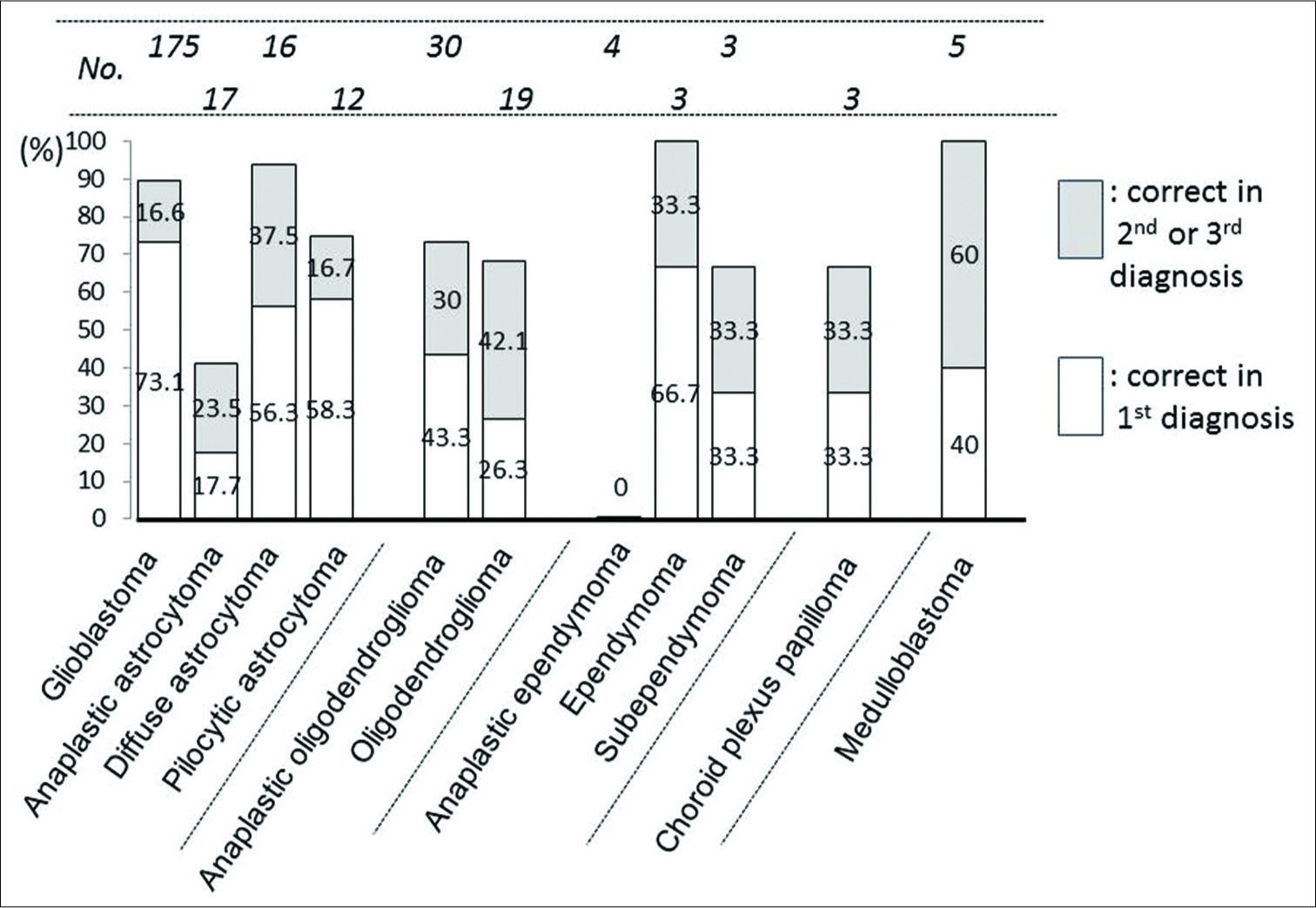

Sensitivity according to the WHO 2007 classification

Among 297 gliomas, the sensitivity of the first differential diagnosis was over 70% only in glioblastoma (73.1%). The sensitivity significantly improved up to 89.7% when the second and third differential diagnoses were included (P = 0.0001, Chi-squared test). In diffuse astrocytoma, ependymoma, and medulloblastoma, the sensitivity of the first diagnosis was under 70%, but it improved over 90% when the second and third differential diagnoses were included. For anaplastic astrocytoma and anaplastic ependymoma, it was still below 50% even on inclusion of the second and third differential diagnoses [

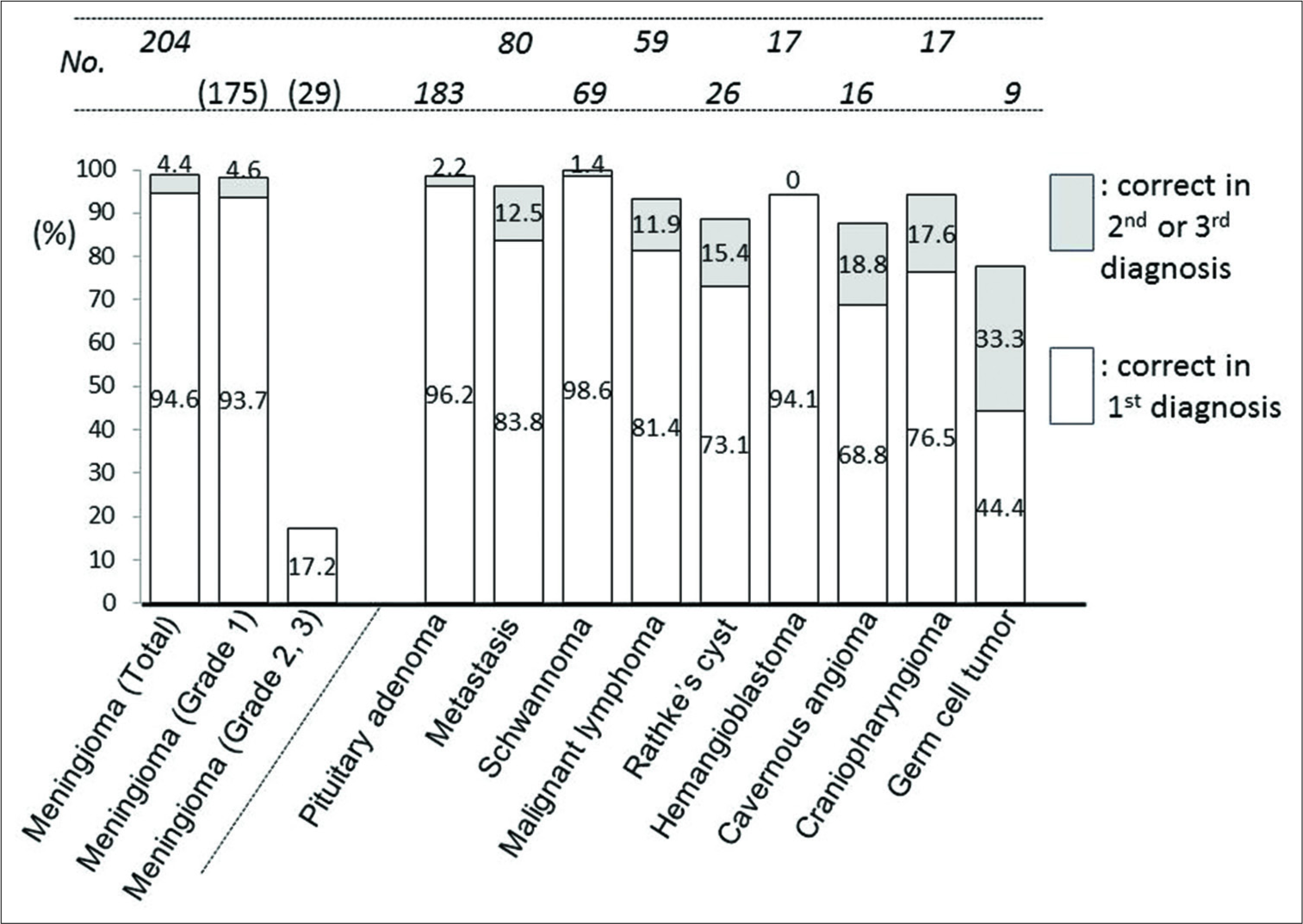

In tumors other than gliomas, sensitivity was generally high. It was over 80% in metastasis, malignant lymphoma, pituitary adenoma, meningioma (overall and Grade 1), hemangioblastoma, and schwannoma; over 90% in the latter four. However, the sensitivity did not reach 20% in Grade 2 + 3 meningioma (21 in atypical, 2 in chordoid, 3 in anaplastic, and 3 in rhabdoid meningioma) [

Positive predictive value (PPV)

PPV was 76.9% (95% CI: 74.5–79.1) in total. The PPV was high in extra-axial tumors (>90%) in pituitary adenoma, schwannoma, and meningioma. Among 297 gliomas, glioblastoma had high PPV of 81.0% (95% CI: 74.8–86.0). However, it did not exceed 50% in other types of gliomas. For meningioma, it was 98.0% (95% CI: 94.8–99.2) in overall and 86.8% (95% CI: 81.7–90.6) in Grade 1 meningioma, whereas it was 62.5% (95% CI: 29.5–86.9) in Grade 2 meningioma [

Specificity, negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy

The specificity, NPV, and accuracy were generally high because of large number of true negative cases. Those were 96.6%, 94.8%, and 92.7% in glioblastoma, respectively. In other 23 kinds of tumors, those values were over 97% [

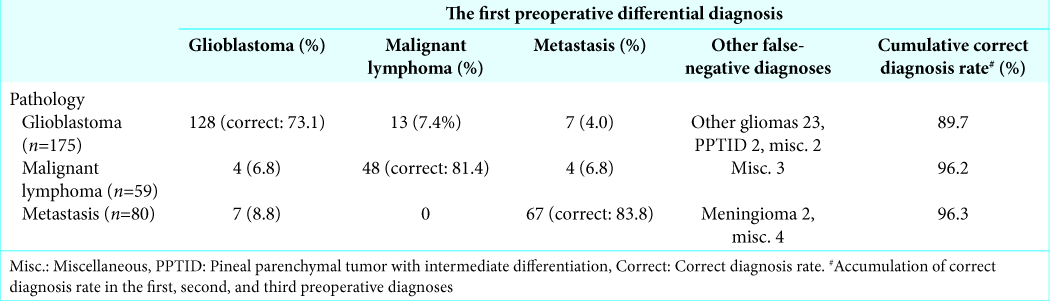

Differential diagnosis of three major intra-axial tumors

Three major malignant neoplasms composed of 68.7% (314/457) of all intra-axial tumors. Sensitivity of the first diagnosis in glioblastoma (175), malignant lymphoma (59), and metastasis (80) was 73.1%, 81.4%, and 83.8%, respectively. PPV was 81.0%, 77.9%, and 72.7%, respectively [

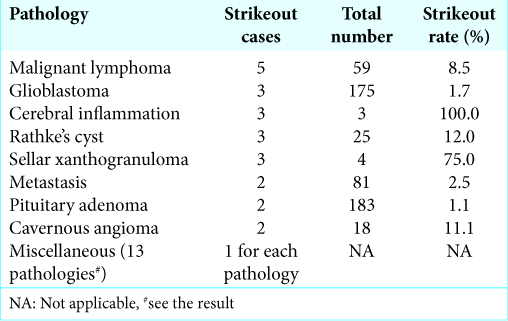

Strikeout lesions

When all three preoperative differential diagnoses for a lesion were incorrect, even broader categorizations were permitted we called the lesion as “strikeout lesion,” consisting 3.4% (36/1061) of all. The frequent “strikeout” lesions included 5 (8.5% of total) malignant lymphomas, 3 (1.7%) glioblastomas, 3 (100%) cerebral inflammatory masses, 3 (12.0%) Rathke’s cleft cysts, and 3 (75%) sellar xanthogranulomas (not registered in the WHO 2007). Following were also “strikeout” lesions; metastasis, pituitary adenoma, cavernous angioma (“hemangioma” in the WHO 2007), hemangioblastoma, craniopharyngioma, malignant melanoma, meningioma, IgG4-related hypophysitis, lymphocytic hypophysitis, schwannoma, teratoma, choriocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumor, fibrous dysplasia, and cerebellar venous infarction [

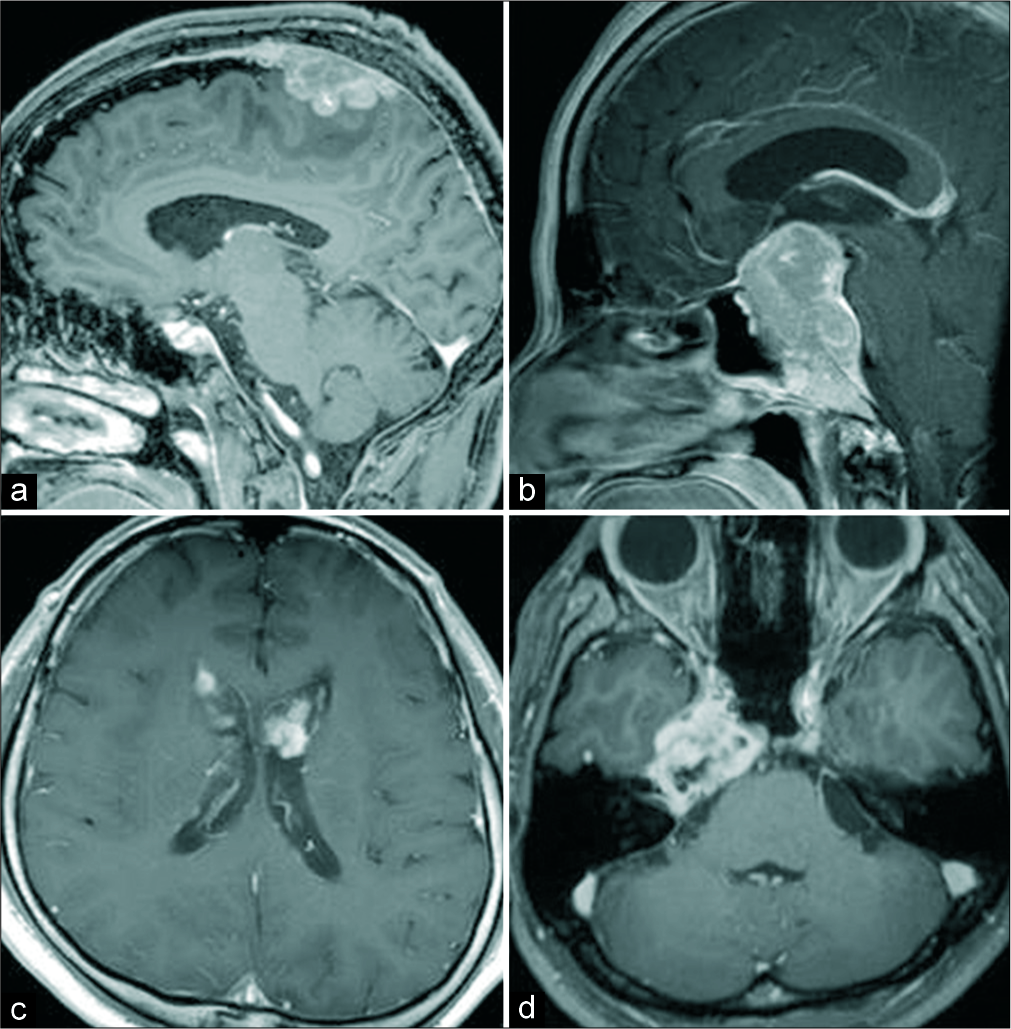

Figure 6:

Representative cases of “strikeout” lesion. Pathological diagnosis and top three preoperative diagnoses. (a) Malignant lymphoma, 1: Grade 1 meningioma, 2: Grade 2 meningioma, 3: Metastasis. (b) Neuroblastoma, 1: Pituitary adenoma, 2: Atypical meningioma, 3: Atypical pituitary adenoma. (c) Subependymoma, 1: Metastasis, 2: Glioblastoma, 3: Choroid plexus carcinoma. (d) Schwannoma, 1: Chordoma, 2: Chondrosarcoma, 3: Plasmacytoma.

DISCUSSION

Our prospective registration study of preoperative differential diagnosis of brain tumor showed that the sensitivity and PPV of the first diagnosis were around 75% in total. The sensitivity improved about 10% when the second and third diagnoses were included. Our study seems very unique because it included all kinds of the intracranial tumors, a total of 1061, and based on not only neuroimaging but also clinical information, eventually testing the efficiency of the preoperative conference as a clinical routine. In addition, this study assessed the significance of the second- and third-tier diagnoses.

We did not have any cases needing reoperation due to inaccuracy of preoperative diagnosis. This is partly because we selected an approach and craniotomy considering the second and third diagnoses could be correct. Moreover, this partly owes to routine intraoperative frozen tissue diagnosis which occasionally corrected surgical strategy during surgery.

It was also noteworthy that there were 3.4% of cases, in which all the three preoperative differential diagnoses were off-targeted.

The previous reports on precision of preoperative diagnosis of brain tumor were mainly from the viewpoint of diagnostic neuroradiologist. In 1995, Hangen et al. reported 76% of sensitivity in preoperative diagnosis of a small series of brain tumors, 173, in their prospective neuroradiologic study.[

Julià-Sapé et al. also assessed the neuroimaging diagnosis in six European institutes and found high specificity, 85.2–100%, and variety of sensitivity depending on the tumor type.[

Yan et al., a neurosurgeons’ team, assessed the MRI reports from neuroradiology section and found sensitivity of 72.0– 90.7% and PPV of 91.9–95.4% in 762 patients.[

In our study, the sensitivities for supra- and infratentorial ventricular tumors were unsatisfactory; 36–42%. The major reason of the low value seems to be wide variety of pathologies in the restricted area, for example, 22 supratentorial intraventricular tumors included glioblastoma, central neurocytoma (Grade 1), atypical central neurocytoma (Grade 2), malignant lymphoma, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, subependymoma, metastasis, cavernous angioma, choroid plexus papilloma (Grade 1), atypical choroid plexus papilloma (Grade 2), simple hematoma, and chordoid glioma. The sensitivity of the pineal gland tumor was also low, 35.7%, for pineal gland tumors which included wide variety of germ cell tumor, glioma, and metastasis.

Sensitivity for tumors in children was significantly lower than in adults in our series. This low sensitivity could be due to the greater population of intraventricular and pineal tumors in children than in adults; 15.2% versus 2.8% and 6.5% versus 1.3%, respectively. The actual sensitivity was 33.3% for both intraventricular and pineal gland tumors in the children. Moreover, another reason may be the absolutely small number of pediatric brain tumors, only 6.6 cases/year, in our institute. This paucity might have hindered the learning curve for our team’s diagnostic ability.

Correct differentiation of the main three intra-axial tumors, malignant lymphoma, metastasis, and glioblastoma, is crucial to make an adequate surgical strategy, ranging from stereotactic biopsy, minimally invasive tumorectomy, and utmost safe resection including resection of nonenhanced but T2-hyperintense lesion and sometimes including lobectomy.[

Perfusion, spectroscopic, and recently developed texture analyses of peritumoral edema may ease the differentiation between glioblastoma and solitary metastasis.[

Compared to acceptable rate of sensitivity and specificity in diagnosis of glioblastoma, preoperative diagnosis of the low-grade glioma is challenging, sensitivity of 56.3% and PPV of 50%, in accordance with the previous report.[

In extra-axial tumors of our series, the sensitivity for high- grade meningioma (Grades 2 and 3) was remarkably lower (17.2%) compared to that for benign meningioma (Grade 1). The most common misdiagnosis for these 29 high-grade meningiomas was Grade 1 meningioma (22 cases) followed by glioblastoma (2 cases). Previously reported sensitivity for high-grade meningioma was also very low.[

Limitation of this study

Recently, it is recommended to use integrated classification system which combines histologic classification and genetic information, such as 1p/19q chromosomal codeletion, IDH- 1 mutation, EGFR amplification, and BRAF mutation.[

We reviewed radiology reports before the conference and the attendance of diagnostic neuroradiology specialists was obtained in half of the cases in this series. Retrospectively, the discussion with neuroradiologists seemed not to be sufficient, considering some correct diagnoses in neuroradiology reports were dismissed and even some “strikeout” lesions were mentioned in the neuroradiology reports. Moreover, radiology reports were often not based on the WHO classification and grading, like “high-grade astrocytoma,” and often equivocal. Radiology reports will be more useful when the final diagnosis becomes more categorical and systematically listed like our three-tier differential diagnosis list.

Strength of this study

In spite of aforementioned limitations, for the first time, this report provides the “real-world” data on efficiency of our preoperative diagnosis in our daily clinical practice. The similar study should be conducted to know the validity of our finding by other high-volume brain tumor centers. The comparison of the value of the precision and routine procedures for preoperative diagnosis between the institutes may widen chance to reach the correct preoperative diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

Our data showed that sensitivity and PPV of our differential diagnosis of the intracranial tumors in the routine preoperative conference were around 75%. It means that the diagnosis has possibility of false positive and false negative in 25%. The second and third diagnoses improved the sensitivity by 10% in general. However, the values varied considerably according to pathologies. The data on tumors of each location and pathology may give us important information for establishing an adequate surgical strategy including the application of stereotactic biopsy, prediction of possible intraoperative alternation of approach, and proper use of intraoperative pathological diagnosis. In addition, these data may be conducive to adequately informing the patients and families. We are now planning the next stage study to investigate whether the routine use of advanced neuroimaging modalities, such as ASL, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, and rCBV parameters, improves the precision of our preoperative diagnosis.

Disclosures

This study was partly financed by Health and Labor Sciences Research Grant on “Research on Intractable Diseases in Japan: Hypothalamo-Pituitary Dysfunction” from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

We declare that each of us participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for this paper content. Moreover, we declare that there are no conflicts of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the paper reported.

Declaration of patient consent

Patients consent not required as patients idenity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors cordially thank Dr. Hirofumi Hirano for his technical support on statistical analysis, Professor Akihide Tanimoto for his advice on pathological assessment, Ms. Tomoko Takajo for her acquisition of pathological data, and Dr. Mika Habu, Dr. Hajime Yonezawa, and Dr. Jun Sugata for their acquisition of clinical data.

References

1. Aghi M, Gaviani P, Henson JW, Batchelor TT, Louis DN, Barker FG. Magnetic resonance imaging characteristics predict epidermal growth factor receptor amplification status in glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005. 11: 8600-5

2. Bauer AH, Erly W, Moser FG, Maya M, Nael K. Differentiation of solitary brain metastasis from glioblastoma multiforme: A predictive multiparametric approach using combined MR diffusion and perfusion. Neuroradiology. 2015. 57: 697-703

3. Brastianos PK, Batchelor TT. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: Overview of current treatment strategies. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2012. 26: 897-916

4. Carrillo JA, Lai A, Nghiemphu PL, Kim HJ, Phillips HS, Kharbanda S. Relationship between tumor enhancement, edema, IDH1 mutational status, MGMT promoter methylation, and survival in glioblastoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012. 33: 1349-55

5. Eckel-Passow JE, Lachance DH, Molinaro AM, Walsh KM, Decker PA, Sicotte H. Glioma groups based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT promoter mutations in tumors. N Engl J Med. 2015. 372: 2499-508

6. Ellison DW, Hawkins C, Jones DT, Onar-Thomas A, Pfister SM, Reifenberger G. cIMPACT-NOW update 4: Diffuse gliomas characterized by MYB, MYBL1, or FGFR1 alterations or BRAFV600E mutation. Acta Neuropathol. 2019. 137: 683-7

7. Ferguson SD, Wagner KM, Prabhu SS, McAleer MF, McCutcheon IE, Sawaya R. Neurosurgical management of brain metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2017. 34: 377-89

8. Guzmán-De-Villoria JA, Mateos-Pérez JM, Fernández-García P, Castro E, Desco M. Added value of advanced over conventional magnetic resonance imaging in grading gliomas and other primary brain tumors. Cancer Imaging. 2014. 14: 35-

9. Hagen T, Nieder C, Moringlane JR, Feiden W, König J. Correlation of preoperative neuroradiologic with postoperative histologic diagnosis in pathological intracranial processes. Radiologe. 1995. 35: 808-15

10. Ichimura K, Pearson DM, Kocialkowski S, Bäcklund LM, Chan R, Jones DT. IDH1 mutations are present in the majority of common adult gliomas but rare in primary glioblastomas. Neuro Oncol. 2009. 11: 341-7

11. Julià-Sapé M, Acosta D, Majós C, Moreno-Torres A, Wesseling P, Acebes JJ. Comparison between neuroimaging classifications and histopathological diagnoses using an international multicenter brain tumor magnetic resonance imaging database. J Neurosurg. 2006. 105: 6-14

12. Kawahara Y, Nakada M, Hayashi Y, Kai Y, Hayashi Y, Uchiyama N. Prediction of high-grade meningioma by preoperative MRI assessment. J Neurooncol. 2012. 108: 147-52

13. Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD, Martinez AJ. Unreliability of contemporary neurodiagnostic imaging in evaluating suspected adult supratentorial (low-grade) astrocytoma. J Neurosurg. 1993. 79: 533-6

14. Lasocki A, Tsui A, Gaillard F, Tacey M, Drummond K, Stuckey S. Reliability of noncontrast-enhancing tumor as a biomarker of IDH1 mutation status in glioblastoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2017. 39: 170-5

15. Law M, Cha S, Knopp EA, Johnson G, Arnett J, Litt AW. High-grade gliomas and solitary metastases: Differentiation by using perfusion and proton spectroscopic MR imaging. Radiology. 2002. 222: 715-21

16. Law M, Yang S, Wang H, Babb JS, Johnson G, Cha S. Glioma grading: Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of perfusion MR imaging and proton MR spectroscopic imaging compared with conventional MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003. 24: 1989-98

17. Li YM, Suki D, Hess K, Sawaya R. The influence of maximum safe resection of glioblastoma on survival in 1229 patients: Can we do better than gross-total resection?. J Neurosurg. 2016. 124: 977-88

18. Lin BJ, Chou KN, Kao HW, Lin C, Tsai WC, Feng SW. Correlation between magnetic resonance imaging grading and pathological grading in meningioma. J Neurosurg. 2014. 121: 1201-8

19. Lin MC, Li CZ, Hsieh CC, Hong KT, Lin BJ, Lin C. Preoperative grading of intracranial meningioma by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS). PLoS One. 2018. 13: e0207612-

20. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016. 131: 803-20

21. Neska-Matuszewska M, Bladowska J, Sąsiadek M, Zimny A. Differentiation of glioblastoma multiforme, metastases and primary central nervous system lymphomas using multiparametric perfusion and diffusion MR imaging of a tumor core and a peritumoral zone-searching for a practical approach. PLoS One. 2018. 13: e0191341-

22. Rockhill J, Mrugala M, Chamberlain MC. Intracranial meningiomas: An overview of diagnosis and treatment. Neurosurg Focus. 2007. 23: E1-

23. Roh TH, Kang SG, Moon JH, Sung KS, Park HH, Kim SH.editors. Survival benefit of lobectomy over gross-total resection without lobectomy in cases of glioblastoma in the noneloquent area: A retrospective study. J Neurosurg. 2019: 1-7

24. Sanai N, Polley MY, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Berger MS. An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. J Neurosurg. 2011. 115: 3-8

25. Schaff LR, Grommes C. Updates on primary central nervous system lymphoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2018. 20: 11-

26. Skogen K, Schulz A, Helseth E, Ganeshan B, Dormagen JB, Server A. Texture analysis on diffusion tensor imaging: Discriminating glioblastoma from single brain metastasis. Acta Radiol. 2019. 60: 356-66

27. Watanabe Y, Yamasaki F, Kajiwara Y, Takayasu T, Nosaka R, Akiyama Y. Preoperative histological grading of meningiomas using apparent diffusion coefficient at 3T MRI. Eur J Radiol. 2013. 82: 658-63

28. Xi YB, Kang XW, Wang N, Liu TT, Zhu YQ, Cheng G. Differentiation of primary central nervous system lymphoma from high-grade glioma and brain metastasis using arterial spin labeling and dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2019. 112: 59-64

29. Yamashita K, Hiwatashi A, Togao O, Kikuchi K, Hatae R, Yoshimoto K. MR imaging-based analysis of glioblastoma multiforme: Estimation of IDH1 mutation status. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016. 37: 58-65

30. Yan PF, Yan L, Zhang Z, Salim A, Wang L, Hu TT. Accuracy of conventional MRI for preoperative diagnosis of intracranial tumors: A retrospective cohort study of 762 cases. Int J Surg. 2016. 36: 109-17