- Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California Irvine Medical Center, Irvine, CA, United States.

- Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, University of California Irvine Medical Center, Irvine, CA, United States.

- Department of Medical Scientist Training Program, University of California Irvine Medical Center, Irvine, CA, United States.

- Department of Biological Chemistry, University of California Irvine Medical Center, Irvine, CA, United States.

- Orthopedic Surgery, University of California Irvine Medical Center, Irvine, CA, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Michael Y. Oh, Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California Irvine Medical Center, Irvine, CA, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_399_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Sandra Gattas1,2,3, Gianna M. Fote1,3,4, Nolan J. Brown1, Brian V. Lien1, Elliot H. Choi1, Alvin Y. Chan1, Charles D. Rosen5, Michael Y. Oh1. Second opinion in spine surgery: A scoping review. 30-Aug-2021;12:436

How to cite this URL: Sandra Gattas1,2,3, Gianna M. Fote1,3,4, Nolan J. Brown1, Brian V. Lien1, Elliot H. Choi1, Alvin Y. Chan1, Charles D. Rosen5, Michael Y. Oh1. Second opinion in spine surgery: A scoping review. 30-Aug-2021;12:436. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11073/

Abstract

Background: As a growing number of patients seek consultations for increasingly complex and costly spinal surgery, it is of both clinical and economic value to investigate the role for second opinions (SOs). Here, we summarized and focused on the shortcomings of 14 studies regarding the role and value of SOs before proceeding with spine surgery.

Methods: Utilizing PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus, we identified 14 studies that met the inclusion criteria that included: English, primary articles, and studies published in the past 20 years.

Results: We identified the following findings regarding SO for spine surgery: (1) about 40.6% of spine consultations are SO cases; (2) 61.3% of those received a discordant SO; (3) 75% of discordant SOs recommended conservative management; and (4) SO discordance applied to a variety of procedures.

Conclusion: The 14 studies reviewed regarding SOs in spine surgery showed that half of the SOs differed from those given in the initial consultation and that SOs in spine surgery can have a substantial impact on patient care. Absent are prospective studies investigating the impact of following a first versus second opinion. These studies are needed to inform the potential benefit of universal implementation of SOs before major spine operations to potentially reduce the frequency and type/extent of surgery.

Keywords: Second opinion, Spine surgery, Discordance rates

INTRODUCTION

Second opinions (SOs) in spine surgery are particularly important as there are tremendous variations regarding indications and types of spinal operations offered/performed.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature review

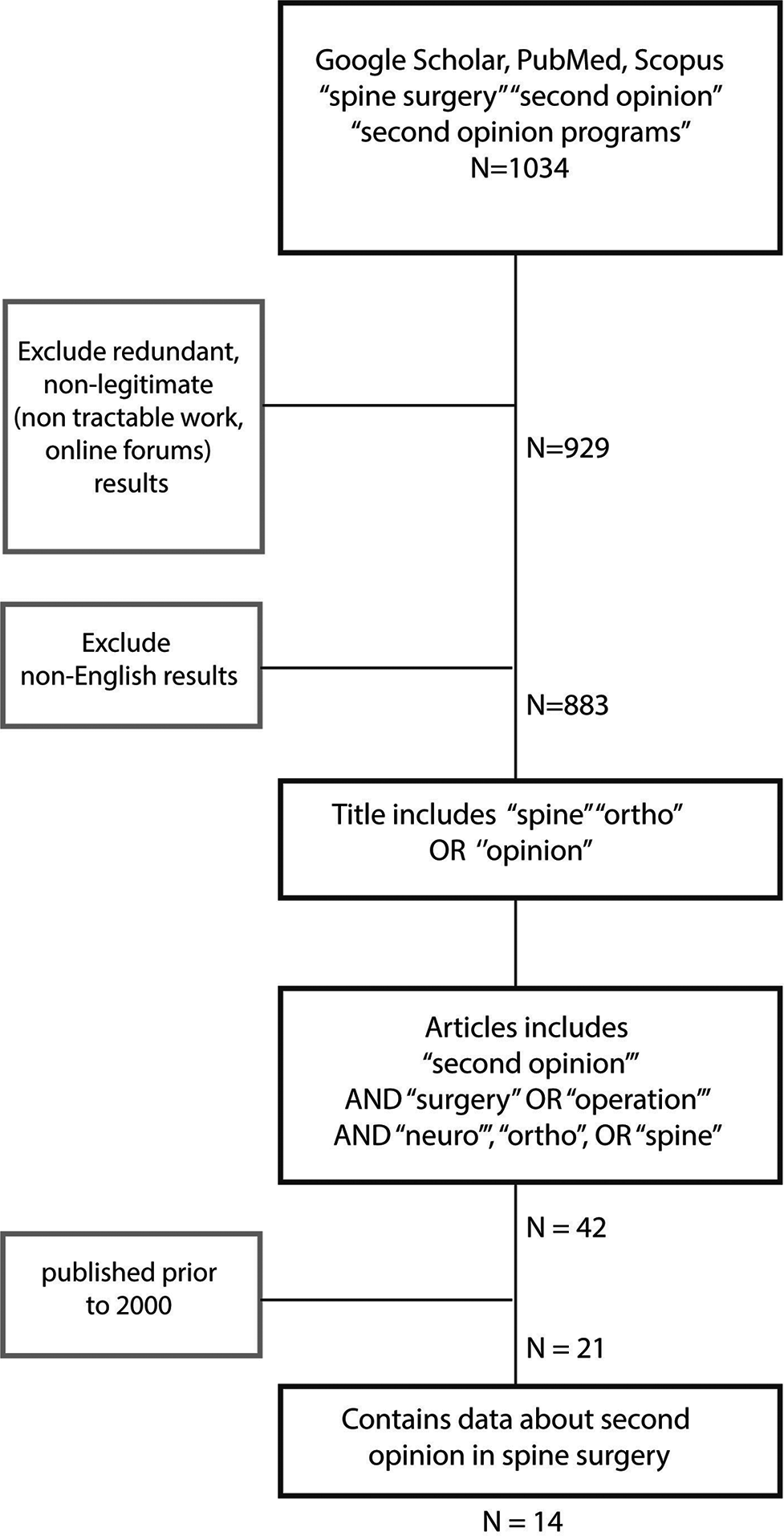

PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases were the search engines utilized to identify 14 peer-reviewed articles on SO before spine surgery; these studies were assessed by two reviewers [

Figure 1:

Study inclusion criteria. Process of exclusion and inclusion of studies for the scoping review. Search terms included: “spine surgery” AND “SO,” and “SO programs.” Primary articles/ titles included “spine,” “orthopedic,” “opinion,” text included (“SO,” “surgery,” “operation”) and (“neuro”/“ortho” “spine”). SO: Second opinion.

Evaluation of potential bias

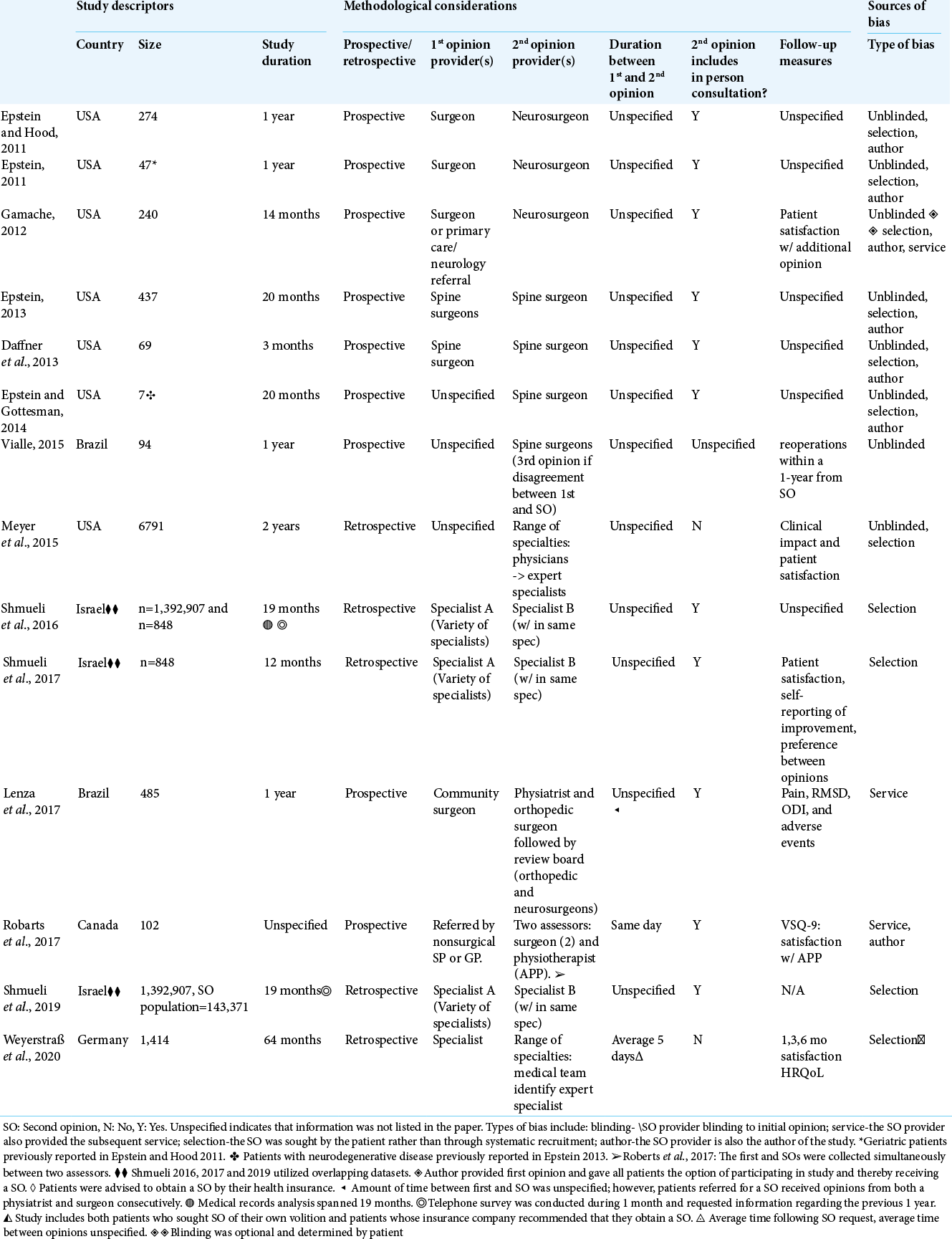

Study descriptors, methodological considerations, and potential sources of bias were noted [

In half of the studies, the SO provider also authored the published work, and in the majority of studies there was the potential for selection bias (i.e., the SO was sought by patients as opposed to systematic recruitment).

Data collection

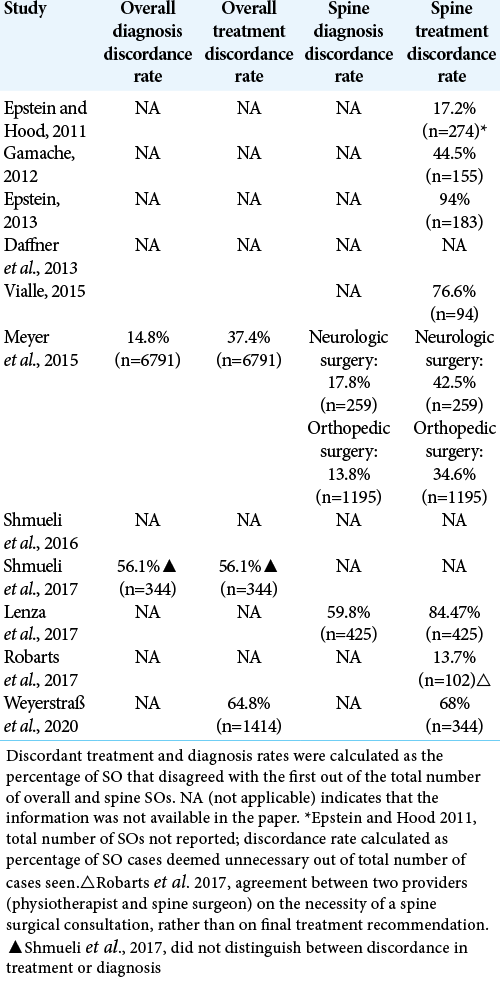

The following data were extracted: SO recommendation for no or different surgery, SO surgery practices across spine specialties, discordance rates between first and SO treatment and diagnosis, discordance rates for specific operations, likelihood for surgical recommendation during a first versus SOs, and patient-reported outcomes [

RESULTS

Two reviewers reached a consensus on 14 articles that were included in this analysis regarding the utility of SO in spinal surgery [

Discordant SO recommendations

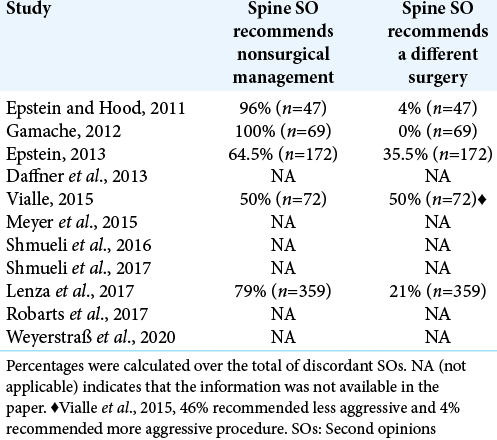

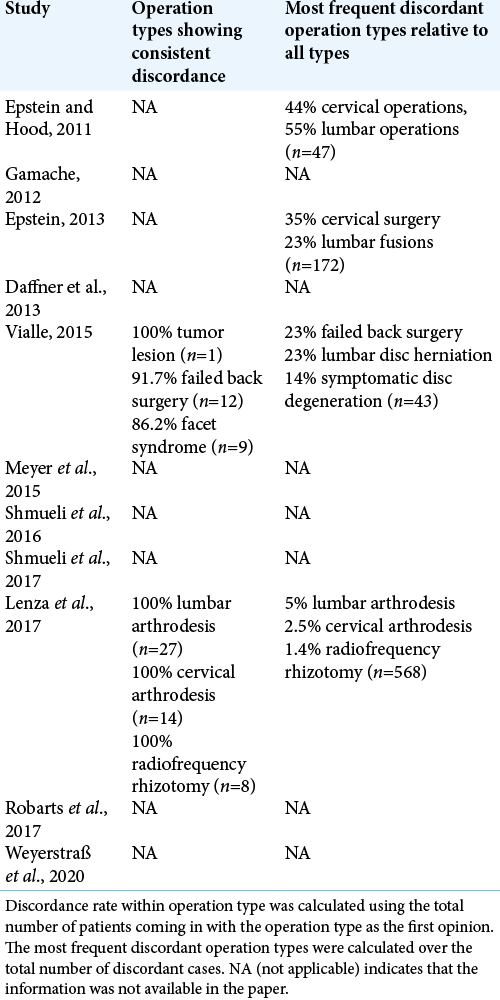

Two categories of discordant SO recommendations were reported in five of the studies: (1) surgery was recommended by the first and not the SO, or (2) the type of surgery recommended by the SO was different from the type recommended by the first surgeon [

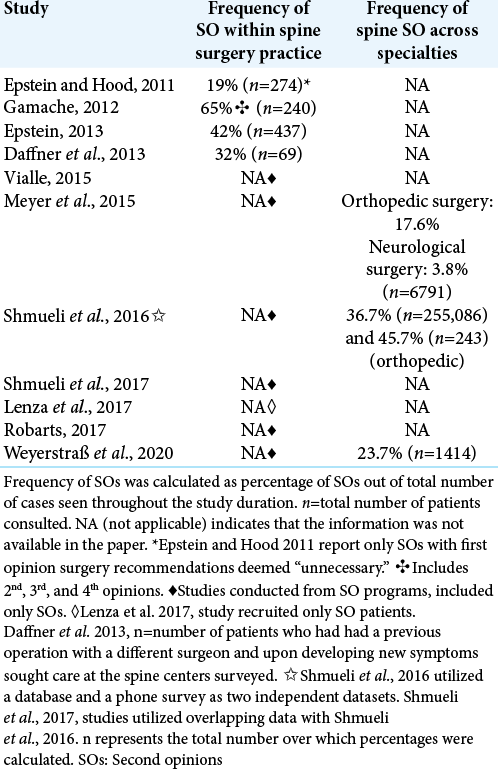

Frequency of SOs in spine surgery practice

Using pooled data across studies, 40.6% (n = 1020) of spine surgery consultations were for a second opinion [

Discordance rates

Discordance rates between first and SOs in spine surgery suggest that SOs provide patients with additional information regarding medical risks and financial costs.

One study reported 59.8% diagnosis discordance in spine surgery for SO[

In another study, concordance was either “confirmed” or “clarified,” possibly deflating discordance values relative to the other studies.[

The estimated rate of SO cases diagnosed as nonspinal was 11.8% (n = 404), including myofascial pain syndrome, multiple sclerosis, lupus, and fibromyalgia.[

In all studies, discordance was observed in all surgical categories reported [

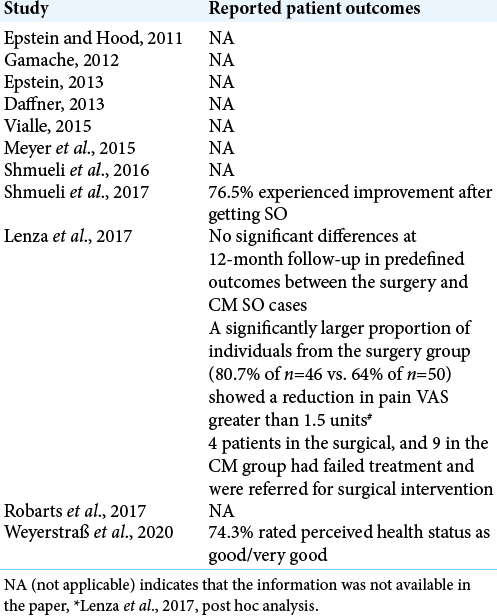

Patient reported outcomes after SO

Two studies included patient self-reports of perceived health (74.3% reported improvement and 76.5% rated health as good/very good) [

DISCUSSION

Approximately half of new visits to spine surgeons (40.6%) are SO consultations. Among those SOs, discordance with first opinion is (59.8%). Many patients seek a SO because they are afraid of having surgery, and the majority of discordant SOs recommend no surgery (75%). SOs, therefore, may inform decisions related to surgical costs and undesirable risks/complications of surgeries.

Factors contributing to discordance rates

Factors contributing to discordance rates would appear to include: variable training between physicians/spine surgeons, the different times elapsed between spine surgical opinions, and the potential changes occurring in the patients’ clinical status between opinions.

In addition, providers of the SO should be separate from those providing the service to avoid any conflict of interest.

CONCLUSION

This report highlights the discordance rates found regarding spinal surgical recommendations between first and SOs. Prospective studies are needed to objectively investigate the impact of following a first versus a SO since, SOs may reduce the physical and financial costs of spine surgery.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

National Institute of Health (NIH): T32 NS45540 and 5F30AG060704-02.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Daffner SD, Hilibrand AS, Riew KD. Why are spine surgery patients lost to follow-up?. Global Spine J. 2013. 3: 15-20

2. Epstein NE, Gottesman M. Few patients with neurodegenerative disorders require spinal surgery. Surg Neurol Int. 2014. 5: S81-7

3. Epstein NE, Hood DC. “Unnecessary” spinal surgery: A prospective 1-year study of one surgeon’s experience. Surg Neurol Int. 2011. 2: 83

4. Epstein NE. Are recommended spine operations either unnecessary or too complex? Evidence from second opinions. Surg Neurol Int. 2013. 4: S353-8

5. Epstein NE. Spine surgery in geriatric patients: Sometimes unnecessary, too much, or too little. Surg Neurol Int. 2011. 2: 188

6. Gamache FW. The value of “another” opinion for spinal surgery: A prospective 14-month study of one surgeon’s experience. Surg Neurol Int. 2012. 3: S350-4

7. Gray DT, Deyo RA, Kreuter W, Mirza SK, Heagerty PJ, Comstock BA. Population-based trends in volumes and rates of ambulatory lumbar spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006. 31: 1957-63

8. Katz JN. Lumbar spinal fusion Surgical rates costs, and complications. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995. 20: 78S-83S

9. Lenza M, Buchbinder R, Staples MP, Dos Santos OF, Brandt RA, Lottenberg CL. Second opinion for degenerative spinal conditions: An option or a necessity? A prospective observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017. 18: 354

10. Meyer AN, Singh H, Graber ML. Evaluation of outcomes from a national patient-initiated second-opinion program. Am J Med. 2015. 128: 1138.e1125-33

11. Oliveira IO, Lenza M, Vasconcelos RA, Antonioli E, Cendoroglo Neto M. Second opinion programs in spine surgeries: An attempt to reduce unnecessary care for low back pain patients. Braz J Phys Ther. 2019. 23: 1-2

12. Robarts S, Stratford P, Kennedy D, Malcolm B, Finkelstein J. Evaluation of an advanced-practice physiotherapist in triaging patients with lumbar spine pain: Surgeon-physiotherapist level of agreement and patient satisfaction. Can J Surg. 2017. 60: 266-72

13. Shmueli L, Davidovitch N, Pliskin JS, Balicer RD, Hekselman I, Greenfield G. Seeking a second medical opinion: Composition, reasons and perceived outcomes in Israel. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2017. 6: 67

14. Shmueli L, Shmueli E, Pliskin JS, Balicer RD, Davidovitch N, Hekselman I. Second medical opinion: Utilization rates and characteristics of seekers in a general population. Med Care. 2016. 54: 921-8

15. Shmueli L, Shmueli E, Pliskin JS, Balicer RD, Davidovitch N, Hekselman I. Second opinion utilization by healthcare insurance type in a mixed private-public healthcare system: A population-based study. BMJ Open. 2019. 9: e025673

16. Vialle E. Second opinion in spine surgery: A Brazilian perspective. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015. 25: S3-6

17. Weyerstraß J, Prediger B, Neugebauer E, Pieper D. Results of a patient-oriented second opinion program in Germany shows a high discrepancy between initial therapy recommendation and second opinion. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020. 20: 237