- Department of Neurosurgery and Neuroendovascular Surgery, Hiroshima City Hiroshima Citizens Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Yusuke Tomita, Department of Neurosurgery and Neuroendovascular Surgery, Hiroshima City Hiroshima Citizens Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_32_2024

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Yusuke Tomita, Shoichi Fukuda, Aiko Kobashi, Yoshihiro Okada, Keigo Makino, Naoya Kidani, Kenichiro Muraoka, Nobuyuki Hirotsune, Shigeki Nishino. Secondary normal pressure hydrocephalus following pituitary apoplexy: A case report. 22-Mar-2024;15:100

How to cite this URL: Yusuke Tomita, Shoichi Fukuda, Aiko Kobashi, Yoshihiro Okada, Keigo Makino, Naoya Kidani, Kenichiro Muraoka, Nobuyuki Hirotsune, Shigeki Nishino. Secondary normal pressure hydrocephalus following pituitary apoplexy: A case report. 22-Mar-2024;15:100. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/12813/

Abstract

Background: Although secondary normal pressure hydrocephalus (sNPH) can occur in various central nervous system diseases, there are no reports of sNPH caused by pituitary lesions. Herein, we present a unique case of sNPH caused by pituitary apoplexy.

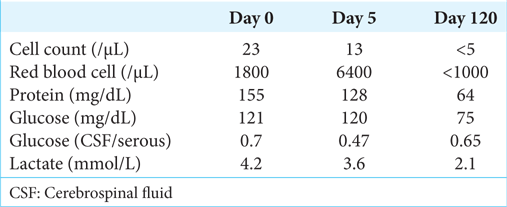

Case Description: A 70-year-old man was transferred to our hospital because of a sudden onset of headache and loss of consciousness. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) test showed slightly elevated cell counts and protein levels but a negative CSF culture test. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a dumbbell-like cystic lesion with hemorrhagic change at the sella turcica. From the above, the patient was diagnosed with aseptic meningitis caused by pituitary apoplexy. Pituitary hormone replacement therapy was undertaken, and his symptoms fully improved. However, two months later, he complained of a gait disturbance and incontinence that had gradually appeared. Brain imaging with computed tomography showed no ventricular enlargement compared with initial images, although the lateral ventricles were slightly enlarged. As a CSF drainage test improved his symptoms temporarily, sNPH with possible longstanding overt ventriculomegaly in adults (LOVA) background was suspected. We performed a lumboperitoneal shunt (LPS) placement, which improved his symptoms.

Conclusion: This case suggests that sNPH can develop even after a small subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by a pituitary apoplexy in LOVA patients. If the aqueduct of Sylvius is open, sNPH with a LOVA background can be successfully treated with LPS placement.

Keywords: Chemical meningitis, Cerebrospinal fluid drainage test, Longstanding overt ventriculomegaly in adults, Pituitary apoplexy, Secondary normal pressure hydrocephalus

INTRODUCTION

Secondary normal pressure hydrocephalus (sNPH) can occur in a number of central nervous system diseases.[

CASE REPORT

The authors obtained written informed consent from the patient. No approval from our institutional review board was sought because this article is a case report. A 70-year-old man complained of a sudden sense of physical weakness and headache, for which he was transferred to the emergency room of our hospital. On arrival, he had a high fever and showed nuchal rigidity. His medical history included diabetes mellitus, hepatocellular carcinoma not induced by viral hepatitis, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, deep venous thrombosis, and angina pectoris, all of which had been appropriately treated. He also had regular visits to our hospital, to which he walked. His medication included antiplatelets and anticoagulants.

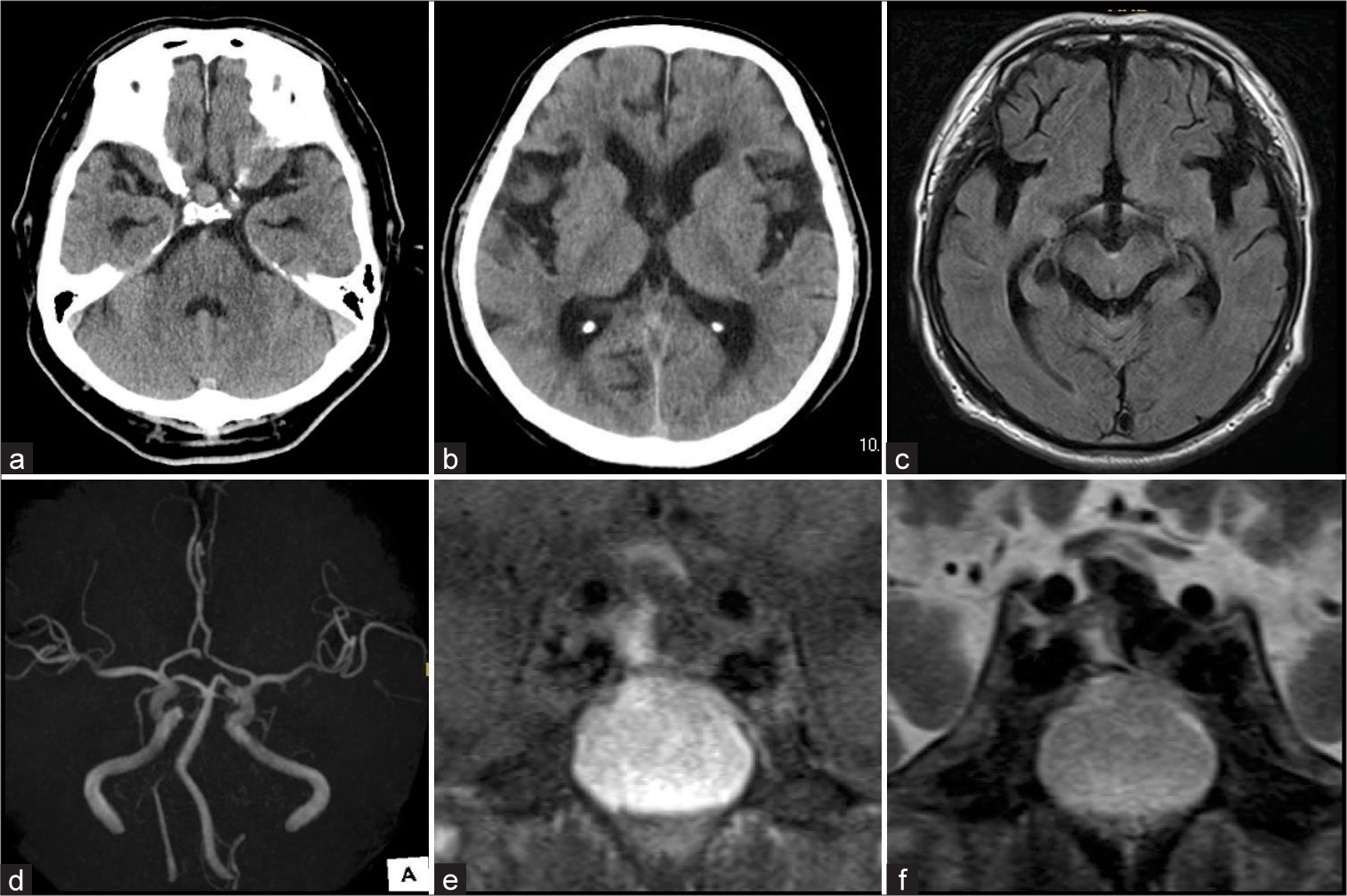

Laboratory tests showed elevated white blood cell counts and C-reactive protein. Whole-body computed tomography (CT) did not detect any apparent abnormality, except for a slightly high-density 10-mm mass in the sella turcica and enlarged lateral ventricles (Evans index, 0.33; callosal angle, 61°) [

Figure 1:

(a and b) Computed tomography imaging. (a) A hyperdense lesion was observed in the sella turcica (9.5 mm in diameter). (b) Lateral ventricles were slightly enlarged. (c-f) Magnetic resonance imaging. (c) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery image showed a hyperintensity lesion in the cerebral peduncle that implied a hematoma. (d) No cerebrovascular lesion was detected on magnetic resonance angiography. (e and f) The coronal images showed that the sellar snowman-like lesion was hypointense on T1-weighted imaging and hypointense with niveau on T2-weighted imaging.

After admission, intravenous acyclovir, vancomycin, and ampicillin were administered for a possible diagnosis of infectious meningitis. Although his laboratory data (including white blood cell counts and C-reactive protein) improved, his consciousness level remained poor, with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 13 (E3V4M6). Repeated brain CT showed no remarkable changes compared with initial images, including for the sellar lesion. However, pituitary MRI showed a dumbbell-like hypointense core with a hyperintense rim on T1-weighted imaging [

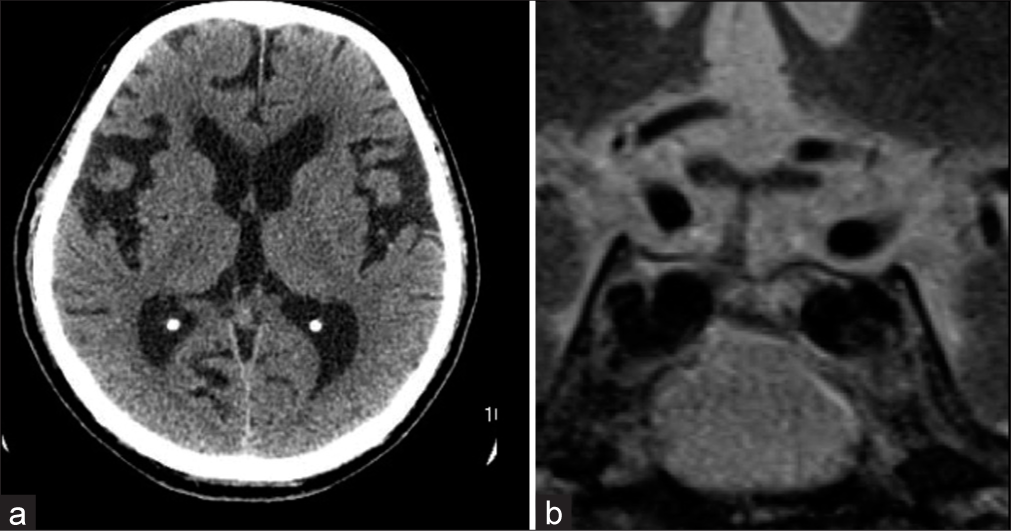

However, two months after discharge, he complained of gait disturbance and incontinence that gradually appeared. Brain CT showed possible hydrocephalus (Evans index, 0.35; callosal angle, 50°), which was similar to the initial CT [

Figure 2:

Imaging at three months after symptom onset. (a) Computed tomography imaging shows the enlarged lateral ventricles, which were similar to the prior images taken at admission. His Evans index was 0.36, and the callosal angle was 54°. (b) Magnetic resonance images showed the resolution of the pituitary lesion on T2-weighted imaging.

DISCUSSION

In the present case, our initial diagnosis was meningitis rather than pituitary apoplexy because of his symptoms and brain imaging findings. However, we eventually diagnosed a pituitary apoplexy following repeated imaging examinations and a negative CSF culture test. At two months after diagnosis, he complained of gait disturbance and mild cognitive impairment, although CT showed almost no further change in his enlarged lateral ventricle. We suspected sNPH based on his CSF tap test, and LPS surgery successfully improved his symptoms.

At admission, the symptoms and CSF results of our case were suggestive of meningitis, although a later CSF culture test did not detect any pathogenic microorganism. The patient also developed sNPH following meningitis. A potential explanation for these findings is that sNPH occurred as a result of pituitary apoplexy-related noninfectious meningitis. Pituitary apoplexy is a rare condition that can occur in a macroadenoma as well as in a normal pituitary gland or microadenoma.[

The present case did not show initial gait disturbance or cognitive impairment, although CT at first admission showed enlarged lateral ventricles. This initial diagnosis may have been related to longstanding overt ventriculomegaly in adults (LOVA) without symptoms. LOVA describes a heterogeneous adult hydrocephalus, which usually has a slow progression.[

In the present case, sNPH was successfully treated with LPS placement, although LOVA may have been present before the onset of pituitary apoplexy. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) is generally recommended in symptomatic LOVA patients, whereas a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) can be considered if the aqueduct of Sylvius is open.[

CONCLUSION

We present a unique case of sNPH following pituitary apoplexy with a possible LOVA background. Clinicians should be aware that sNPH can develop even after a small subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by pituitary apoplexy in LOVA patients. If the aqueduct of Sylvius is open, sNPH with a LOVA background can be successfully treated with LPS placement.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juntaro Fujita and Shohei Nishigaki for providing us with critical comments.

References

1. Abbara A, Clarke S, Eng PC, Milburn J, Joshi D, Comninos AN. Clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients presenting with pituitary apoplexy. Endocr Connect. 2018. 7: 1058-66

2. Alsayadi S, Ochoa-Sanchez R, Moldovan ID, Alkherayf F. Cerebral vasospasm as a consequence of pituitary apoplexy: Illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons. 2023. 5: CASE22349

3. Gillespie CS, Fang WY, Lee KS, Clynch AL, Alam AM, McMahon CJ. Long-standing overt ventriculomegaly in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of endoscopic third ventriculostomy versus ventriculoperitoneal shunt as first-line treatment. World Neurosurg. 2023. 174: 213-20.e2

4. Huang WY, Chien YY, Wu CL, Weng WC, Peng TI, Chen HC. Pituitary adenoma apoplexy with initial presentation mimicking bacterial meningoencephalitis: A case report. Am J Emerg Med. 2009. 27: 517.e1-4

5. Ibáñez-Botella G, González-García L, Carrasco-Brenes A, RosLópez B, Arráez-Sánchez M. LOVA: The role of endoscopic third ventriculostomy and a new proposal for diagnostic criteria. Neurosurg Rev. 2017. 40: 605-11

6. Liao CL, Tseng PH, Huang HY, Chiu TL, Lin SZ, Tsai ST. Lumbar-peritoneal shunt for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus and secondary normal pressure hydrocephalus. Tzu Chi Med J. 2022. 34: 323-8

7. Nakajima M, Yamada S, Miyajima M, Ishii K, Kuriyama N, Kazui H. Guidelines for management of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (third edition): Endorsed by the Japanese Society of normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2021. 61: 63-97

8. Nawar RN, AbdelMannan D, Selman WR, Arafah BM. Pituitary tumor apoplexy: A review. J Intensive Care Med. 2008. 23: 75-90

9. Randeva HS, Schoebel J, Byrne J, Esiri M, Adams CB, Wass JA. Classical pituitary apoplexy: Clinical features, management and outcome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999. 51: 181-8

10. Skalický P, Mládek A, Vlasák A, De Lacy P, Beneš V, Bradáč O. Normal pressure hydrocephalus-an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and diagnostic procedures. Neurosurg Rev. 2020. 43: 1451-64

11. Tumyan G, Mantha Y, Gill R, Feldman M. Acute sterile meningitis as a primary manifestation of pituitary apoplexy. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2021. 7: 117-20