- Department of Neurosurgery, Desert Regional Medical Center, Palm Springs, California, United States.

- College of Literature, Arts, and Sciences, University of Michigan, Flint, Michigan, United States.

- Medical School, University of Medicine and Health Sciences, New York, United States.

- School of Medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Brian Fiani

School of Medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_15_2021

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Brian Fiani1, Ryan Jarrah2, Nicholas J. Fiani3, Juliana Runnels4. Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma: Insight into this occurrence with case examples. 02-Mar-2021;12:79

How to cite this URL: Brian Fiani1, Ryan Jarrah2, Nicholas J. Fiani3, Juliana Runnels4. Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma: Insight into this occurrence with case examples. 02-Mar-2021;12:79. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10620/

Abstract

Background: First characterized in the 19th century, spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma (SSEH) is known as the idiopathic accumulation of blood within the spinal canal’s epidural space, causing symptoms varying from general back pain to complete paraplegia. With varying etiologies, a broad spectrum of severity and symptoms, a time-dependent resolution period, and no documented diagnosis or treatment algorithm, SSEH is a commonly misunderstood condition associated with increasing morbidity. While SSEH can occur at any vertebrae level, 16% of all SSEH cases occur in the cervical spine, making it a region of interest to clinicians.

Case Description: Herein, the authors present two case examples describing the clinical presentation of SSEH, while also reviewing the literature to provide a comprehensive overview of its presentation, pathology, and treatment. The first case is a patient with nontraumatic sudden onset neck pain with rapidly progressing weakness. The second case is a patient with painless weakness that developed while taking 325 mg of aspirin daily.

Conclusion: Clinicians should keep SSEH in their differential diagnosis when seeing patients with nontraumatic sources of weakness in their extremities. The appropriate steps should be followed to diagnose and treat this condition with magnetic resonance imaging and surgical decompression if there are progressive neurological deficits. There is a continued need for more extensive database-driven studies to understand better SSEHs clinical presentation, etiology, and ultimate treatment.

Keywords: Epidural hematoma, Idiopathic hematoma, Spinal epidural hematoma, Spontaneous hematoma, Spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas (SSEHs) are rare and complex spinal pathologies that have led to devastating neurologic outcomes among its patient population that has otherwise not had devastating trauma or explainable causes. Namely, SSEH is a condition where blood accumulates in the epidural space of the spinal column and ultimately compresses the spinal cord and nerve roots, leading to symptoms ranging from back pain to quadriplegia.[

Despite its profound clinical consequences, SSEH is a highly misunderstood condition that requires proper identification by clinicians and patients alike to avoid devastating neurologic sequelae.[

CASE EXAMPLES

Case 1

Clinical presentation

We present a 52-year-old right-handed Caucasian male with a medical history of HIV, hepatitis C, hypertension, and type II diabetes with a chief complaint of sudden onset severe upper back pain. The patient stated that the upper back pain started while he was conducting a Zoom lecture as a math teacher. He denied any trauma or injuries. He also denied any regular use of anticoagulant medications, but did take aspirin 81 mg daily for general cardiovascular health. He also denied any subjective fever or chills. He stated that the pain was 8/10 in severity. Within hours, he started to notice weakness in his right and right hand which prompted him to call the ambulance and was brought to the hospital. As the weakness became more severe, he began to develop numbness in the right hand and right leg. The patient was admitted and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine was performed.

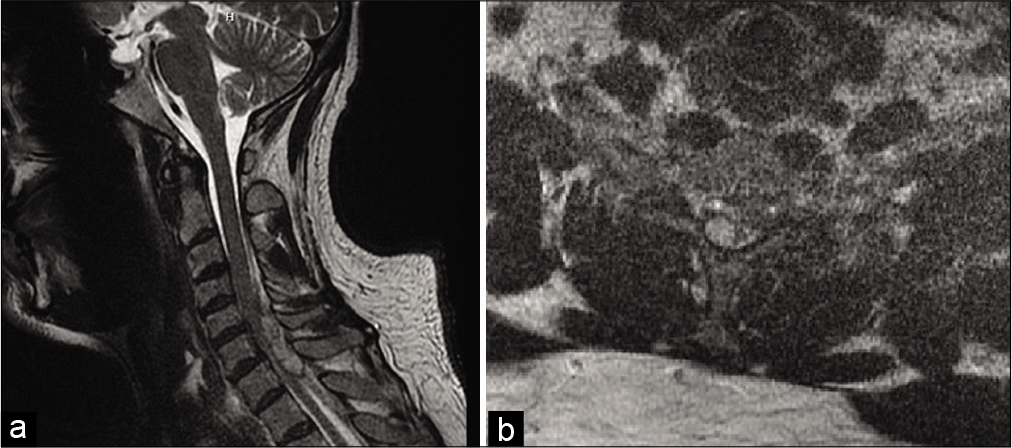

Radiographically, MRI of the cervical spine without contrast revealed an epidural fluid collection identified posterior to the cord at the C4-C7 levels measuring up to 1 cm thick [

Figure 1:

T2-weighted MRI of the cervical spine showing hyperintense epidural fluid collection with low T2 signal rim identified posterior to the cord on (a) sagittal view and (b) eccentric toward the right on axial view, at the C4-C7 levels measuring up to 1 cm thick. The cord appears compressed most pronounced at the C6 and C7 levels with mild increased cord signal.

The patient was emergently taken to the operating room for posterior C5-C7 decompressive laminectomy and evacuation of intra-SEH. On removal of the lamina and ligamentum flavum, there was visualization of epidural hematoma. The purple, clotted, thick, gelatinous material was completely evacuated and sent to pathology for confirmation. There was no obvious vascular malformation noted and there did not appear to be any trauma in the adjacent soft tissues. There did not appear to be any unusual bleeding problems intraoperatively. Complete evacuation of hematoma and decompression was achieved. The histopathological specimen consisted of a 2 × 2 × 1 cm aggregate of dark brown-purple clotted blood fragments. The pathological diagnosis confirmed SHE with no malignancy cells. The patient was returned to his hospital room for continued recovery and physical therapy rehabilitation. He was subsequently discharge to acute rehabilitation facility. The above patient represents a case of idiopathic SSEH.

Case 2

Clinical presentation

We present a 72-year-old right hand dominant Caucasian female transferred from outside hospital status – post sudden onset severe left neck pain and left arm pain. She stated that her neck pain started the night prior and suddenly started radiating into her left shoulder and arm which was associated with progressive weakness. Her pain was made worse by any movement. She denied any preceding trauma. She denies any medical history other than hypertension. Of note, she stated that she does take 325 mg aspirin daily for joint pain. She denies having any known bleeding disorder but stated that she tends to bruise easily. Her coagulation laboratories indicated aspirin therapeutic response causing platelet dysfunction: platelet EPI >300 (normal 72–184) and platelet function aspirin 560 (normal 570–675). Her platelet count was 400 and other laboratory work noncontributory. Her physical examination was significant for having motor deficits as follows: left upper extremity: 4/5 deltoid, 4/5 bicep, 3/5 triceps, 2/5 wrist extension, 2/5 wrist flexion, 4/5 handgrip, and 2/5 interosseous muscles, left lower extremity: 4+/5 hip flexion, 5/5 knee flexion, 5/5 knee extension, 4+/5 dorsiflexion, 5/5 plantar flexion, and 5/5 extensor hallucis longus. She also had sensory deficits in the left upper extremity which displayed decreased sensation to pinprick in a nondermatomal distribution.

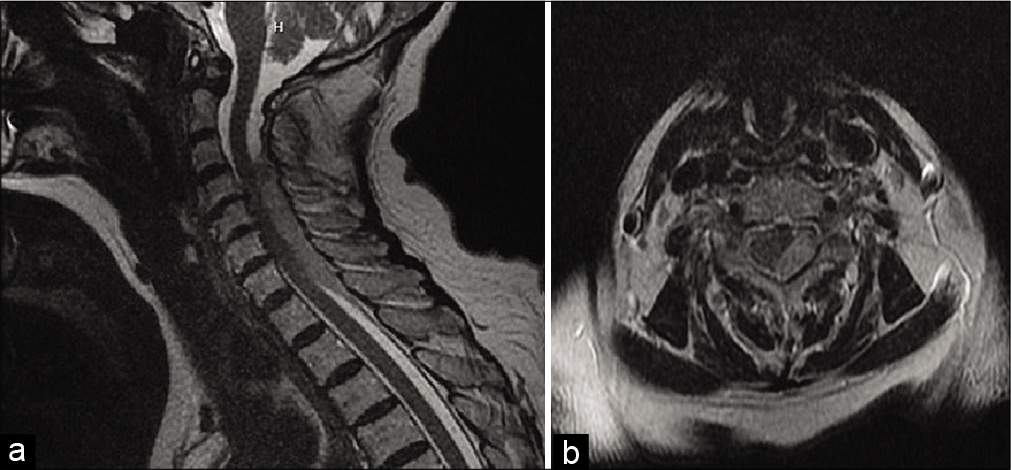

Radiographically, MRI of the cervical spine showed an epidural hematoma dorsal to the cord at the C3-T2 levels measuring up to 6 mm thick [

She was taken to surgery within hours of presentation for emergent posterior C3-C7 decompressive laminectomies and evacuation of intra-SEH. There were findings of dorsal purple clotted epidural hematoma that was eccentric to the left. Operatively, there was complete decompression achieved and hematoma was entirely evacuated. Baseline intraoperative neuromonitoring showed decreased motor signals in bilateral upper extremities, left worse than right. The SSEP sensory signals were normal and stable throughout the surgery. After decompression and evacuation, there was identifiable improvement in bilateral upper extremity motor signals on intraoperative neuromonitoring.

Postoperatively, within the first 24 h period, she had near resolution of her weakness with only residual weakness of 4+/5 wrist extension, 4+/5 wrist flexion, 4/5 handgrip, and 4/5 interosseous muscle. She continued to have left upper extremity decreased sensation to pinprick testing in nondermatomal fashion that was stable. She worked with the physical and occupational therapy teams and was subsequently discharged home with outpatient physical therapy and recommendations to discontinue her daily aspirin use. The above case represents SSEH likely resultant from daily aspirin usage.

DISCUSSION

Etiology

The etiology of SSEH is generally unknown, yet it has been widely investigated.[

Epidemiology

Historical epidemiological literature suggests that SEHs have been clinically investigated since the mid-to-late 19th century.[

Pathophysiology

At present, it is uncertain whether SSEHs originate from the arterial or venous system. Both theories have been proposed, however, venous origins are more widely accepted due to the fact that spinal epidural veins are valveless, making them susceptible to damage from abdominal or thoracic pressure.[

Management principles

At the moment, there is no conclusive answer regarding the best practice for SSEH workup and treatment. With a low prevalence, unknown etiology, and a variety of symptoms, treating such a condition has raised profound challenges that prevent a simple generalized treatment. Nevertheless, SSEH is managed using two methods: conservative or surgical. The traditional treatment for SSEH has been through surgical intervention, with decompressive laminectomy with hematoma evacuation being the common procedure. However, several reports do find that conservative methods have led to spontaneous resolution of SSEH when patients are not experiencing neurological deficits.

Conservative methods

The conservative method has been shown to be growing increasingly among patients who are treated for SSEH. Namely, conservative management means treating back and neck conditions using nonsurgical methods. This includes the use of injections, drug therapy, or physical therapy. In a SSEH case report, pharmacological conservative management was performed using steroids by giving the patient a dexamethasone loading dose of 10 mg IV followed by a 4 mg IV or PO every 4 h and tapering down.[

Surgical methods

As mentioned, surgical management has been the preferred method for definitive treatment of SEEH with the standard operative procedure being a decompressive laminectomy with hematoma evacuation.[

Diagnosis/prognosis

Unfortunately, SSEH is a rare condition that is commonly misdiagnosed.[

Additional laboratories and diagnostic tests should be performed when finding SSEH. CBC (complete blood count) with platelets is done to determine and rule out the presence of an infection while assessing hemorrhagic risk regarding platelet count. Prothrombin time (PT)/activated partial thromboplastin time could also be ordered to determine bleeding diathesis.[

For SSEH, MRI can accurately portray the presence of the hematoma while also finding any possible vascular malformations or epidural abscess. The MRI can also estimate the age and extent of the hematoma along with the degree of cord compression and myelomalacia.[

Liao et al. proposed an algorithm to describe severity of cases, with progressive deterioration and ASIA scores between B-D and ASIA A scores lasting more than hours requiring “emergent surgery.” ASIA A scores lasting less than 12 h are considered “urgent,” while improving cases with ASIA D score are deemed to be solely monitored.[

CONCLUSION

SSEH will continue to be investigated as one of the most curious pathologies in spinal care. Moreover, with a wide clinical presentation spectrum, it is important that patients identify and seek immediate neurologic attention when experiencing symptoms such as sudden radiating back or neck pain, lower extremity weakness, or motor/sensory dysfunctions. From the clinical standpoint, it is paramount that suspected SSEH patients undergo the proper screening in a timely fashion. MRI showing T2 hyperintensity within the spinal cord within 24 h is a poor prognostic indicator. Depending on the patient’s ASIA score, along with the time interval between symptom manifestation and treatment, conservative or surgical management techniques could be performed. Surgical management is considered the gold standard in resolving cases of SSEH with neurological deficits, however, conservative management has also shown success in patients with radicular symptoms or more mild pathological courses.

SSEH is sometimes wrongly misdiagnosed. Its rarity brings obstacles to neurologic research because it becomes harder to create a randomized and controlled trial when the incidence being so little while also hampering the collection of data and clinical outcomes. Further research is warranted for SSEH, where more risk factors are identified and parameters are created to determine treatment success. At present, there are no clear published data on recovery prognostication or their associated time periods. In conclusion, SSEH will remain to be a complex and serious diagnosis, and by further investigating its pathology, clinicians can aim for better treatment and education of its future patients.

Declaration of patient consent

Institutional Review Board permission obtained for the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Al-Mutair A, Bednar DA. Spinal epidural hematoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010. 18: 494-502

2. Aycan A, Ozdemir S, Arslan H, Gonullu E, Bozkina C. Idiopathic thoracic spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma. Case Rep Surg. 2016. 2016: 5430708

3. Counselman FL, Tondt JM, Lustig H. A case report: The challenging diagnosis of spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2020. 4: 428-31

4. Dimou J, Jithoo R, Morokoff A. Spontaneous spinal epidural haematoma in a geriatric patient on aspirin. J Clin Neurosci. 2010. 17: 142-4

5. Gopalkrishnan CV, Dhakoji A, Nair S. Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma of idiopathic etiology: Case report and review of literature. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012. 35: 113-7

6. Halim TA, Nigam V, Tandon V, Chhabra HS. Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma: Report of a case managed conservatively. Indian J Orthop. 2008. 42: 357-9

7. Kao FC, Tsai TT, Chen LH, Lai PL, Fu TS, Niu CC. Symptomatic epidural hematoma after lumbar decompression surgery. Eur Spine J. 2015. 24: 348-57

8. Kim T, Lee CH, Hyun SJ, Yoon SH, Kim KJ, Kim HJ. Clinical outcomes of spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: A comparative study between conservative and surgical treatment. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012. 52: 523-7

9. Kreppel D, Antoniadis G, Seeling W. Spinal hematoma: A literature survey with meta-analysis of 613 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2003. 26: 1-49

10. Matsumura A, Namikawa T, Hashimoto R, Okamoto T, Yanagida I, Hoshi M. Clinical management for spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: Diagnosis and treatment. Spine J. 2008. 8: 534-7

11. Nelson ABenzon HJabri R. Diagnosis and Management of Spinal and Peripheral Nerve Hematoma. Available from: https://www.nysora.com/foundations-of-regional-anesthesia/complications/diagnosis-management-spinal-peripheral-nerve-hematoma [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 04].

12. Oh JY, Lingaraj K, Rahmat R. Spontaneous spinal epidural haematoma associated with aspirin intake. Singapore Med J. 2008. 49: e353-5

13. Park JH, Park S, Choi SA. Incidence and risk factors of spinal epidural hemorrhage after spine surgery: A cross-sectional retrospective analysis of a national database. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020. 21: 324

14. Phang ZH, Chew JJ, Thurairajasingam JA, Ibrahim SB. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma associated with the use of low-dose aspirin in elderly patient. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2018. 2: e059

15. Raasck K, Habis AA, Aoude A, Simoes L, Barros F, Reindl R. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma management: A case series and literature review. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2017. 3: 16043

16. Rahangdale R, Coburn J, Streib C. Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma mimicking acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2020. 95: 496-7

17. Tamburrelli FC, Meluzio MC, Masci G, Perna A, Burrofato A, Proietti L. Etiopathogenesis of traumatic spinal epidural hematoma. Neurospine. 2018. 15: 101-7

18. Teles P, Correia JP, Pappamikail L, Lourenco A, Romero C, Lopes F. A spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma mimicking a stroke-a case report. Surg Neurol Int. 2020. 11: 157

19. Unnithan AK. A brief review of literature of spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in the context of an idiopathic spinal epidural hematoma. Egypt J Neurosurg. 2019. 34: 21

20. Xian H, Xu LW, Li CH, Hao JM, Wan WX, Feng GD. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas: One case report and rehabilitation outcome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017. 96: e8473

21. Zhao W, Shu LF, Cai S, Zhang F. Acute cervical and thoracic ventral side spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma causing high paraplegia: A case report. Anesth Pain Med. 2017. 7: e14041

22. Zuo B, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Song J, Jiang S, Zhang X. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: A case report. Case Rep Orthop Res. 2018. 1: 27-34