- Department of Neurosurgery, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia.

- Department of Undergraduate Program in Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia.

Correspondence Address:

Andre Marolop Pangihutan Siahaan, Department of Neurosurgery, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_608_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Andre Marolop Pangihutan Siahaan1, Steven Tandean1, Bahagia Willibrordus Maria Nainggolan2. Spontaneous epidural hematoma induced by rivaroxaban: A case report and review of the literature. 16-Sep-2022;13:420

How to cite this URL: Andre Marolop Pangihutan Siahaan1, Steven Tandean1, Bahagia Willibrordus Maria Nainggolan2. Spontaneous epidural hematoma induced by rivaroxaban: A case report and review of the literature. 16-Sep-2022;13:420. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11871/

Abstract

Background: Trauma is the most frequent reason for epidural bleeding. However, numerous investigation had discovered that anticoagulants such as rivaroxaban could cause epidural hematoma. Here, we present a case of epidural hematoma in young man who got rivaroxaban as treatment of deep vein thrombosis.

Case Description: A 27-year-old male with a history of deep vein thrombosis and one month of rivaroxaban medication presented with seizure and loss of consciousness following a severe headache. A CT scan of the head revealed epidural bleeding, and emergency blood clot removal was performed. As a reversal, prothrombin complex was utilized.

Conclusion: Rivaroxaban has the potential to cause an epidural hemorrhage. Reversal anticoagulant should be administered before doing emergency surgery.

Keywords: Case report, Epidural hematoma, Prothrombin complex concentrate, Rivaroxaban, Spontaneous epidural hematoma

BACKGROUND

Rivaroxaban is a factor Xa inhibitor that may have a more steady and predictable anticoagulant effect than warfarin.[

CASE PRESENTATION

A 27-year-old man presented with a sudden onset seizure and a loss of consciousness following a severe headache. The neurological examination revealed a GCS of 9/15 with unequal pupils (L>R) and left hemiparesis. He was prescribed rivaroxaban 15 mg twice daily for 1 month after being diagnosed with DVT. There was no history of trauma, abnormalities of vascular, bleeding disorder, infection, or cancer, according to the patient’s medical history.

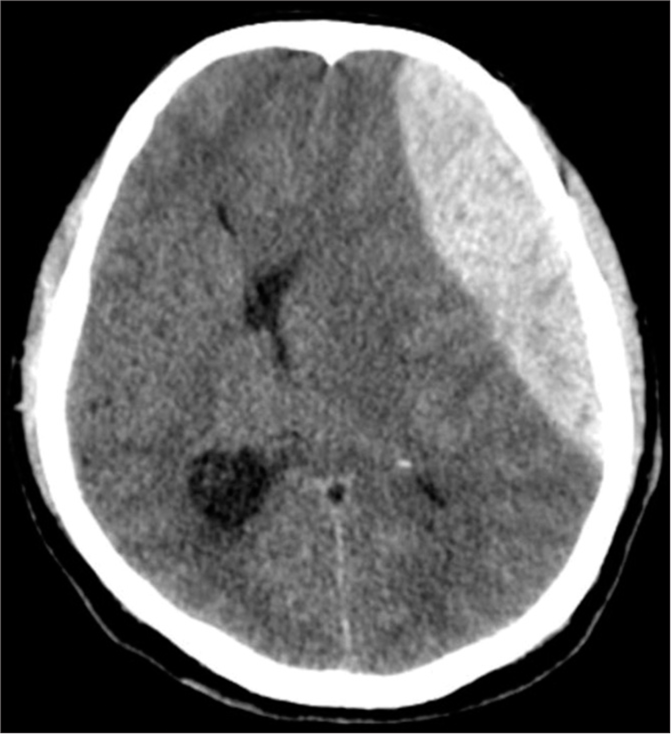

The laboratory detected a rise in D-dimer (1500, compared to 500 as a standard). The prothrombin time, INR, activated partial thromboplastin time, and thrombin time were all within the normal range. On head CT, a biconvex, hyperdense lesion consistent with epidural hemorrhage was observed on the left frontal and parietal, with a volume of 50 cc and midline shift [

To remove the epidural hematoma, an emergency craniotomy was performed. There was no evidence of a fractured skull, but the duramater revealed extensive and diffuse bleeding. There was no indication of infection, vascular abnormality, or cancer. Closure was accomplished following dura tenting and meticulous blood control. For reversal, 50 units/kg of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) were administered in three doses as a reversal agent. First dose was administered during surgery, second dose was administered after surgery, and third dose was administered 24 h after surgery.

On the following day, the patient regained consciousness. At 1-year follow-up, the patient was doing well and has no neurologic deficit.

DISCUSSION

The most common cause of epidural hematoma is trauma.[

Anticoagulant treatment is standard for DVT. Heparin is the preferred drug, but it requires frequent monitoring and has multiple drug and food interactions.[

In the EINSTEIN trial, it was determined that the risk of bleeding was significantly lower with rivaroxaban than with warfarin therapy. Intracerebral bleeding was the leading cause of fatal bleeding, which rivaroxaban appears to reduce.[

After 1 month of rivaroxaban treatment for DVT, the patient in this case developed epidural hematoma. Numerous studies reported rivaroxaban-related epidural hematoma.[

Commonly epidural hematomas are caused by damage to the middle meningeal artery or its terminal arterial branches (in around 55% of patients), the middle meningeal vein (in 30% of instances), and diploic veins or a ruptured dural venous sinus in the remaining 15%. However, this condition could be worse in the event of a diastatic fracture, in which distinct blood clots are present.[

Few studies have reported the incidence of spontaneous epidural spinal bleeding after rivaroxaban administration. Approximately 10–20 mg of rivaroxaban per day is associated with nontraumatic spinal hematoma incidence.[

A significant disadvantage of rivaroxaban therapy is the limited knowledge of monitoring methods for bleeding complications. Some of these assessments are quantitative, while others only provide qualitative data. In addition, it is essential to note that the availability of Xa antifactor tests was limited in Indonesia.[

A study suggests administering activated charcoal (50 g) to intubated intracranial hemorrhage patients with enteral access and/or those at low risk of aspiration who present within 2 h of oral direct factor Xa inhibitor ingestion.[

A study reported anticoagulation reversal strategies should be established without delaying surgical management. In elective surgery, discontinuing rivaroxaban at least 24 h before the procedure is sufficient to normalize the risk of bleeding associated with the drug. In emergency surgery, anti-Factor Xa levels had to be measured. The risk of drug-induced bleeding decreases with each hour between the last rivaroxaban dose and surgery.[

CONCLUSION

Despite the fact that rivaroxaban, a factor Xa inhibitor seems to be a better medication, doctors need to be familiar with its clinical profile, reversal medications, and management strategies in the event of substantial bleeding. Without postponing surgical care, anticoagulation reversal techniques should be developed using andexanet alfa. In contrast, PCC may be used as an anticoagulant reversal if andexanet alfa was not accessible.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Bang WS, Kim KT, Park MK, Sung JK, Lee H, Cho DC. Acute spinal subdural hematoma in a patient taking rivaroxaban. J Korean Med Sci. 2018. 33: e40

2. Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD, Brenner B, Buller HR, Decousus H, Gallus AS. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010. 363: 2499-510

3. Becattini C, Sembolini A, Paciaroni M. Resuming anticoagulant therapy after intracerebral bleeding. Vascul Pharmacol. 2016. 84: 15-24

4. Chatterjee S, Sardar P, Biondi-Zoccai G, Kumbhani DJ. New Oral anticoagulants and the risk of intracranial hemorrhage: Traditional and bayesian meta-analysis and mixed treatment comparison of randomized trials of new oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. JAMA Neurol. 2013. 70: 1486-90

5. Chen H, Guo Y, Chen SW, Wang G, Cao HL, Chen J. Progressive epidural hematoma in patients with head trauma: Incidence, outcome, and risk factors. Emerg Med Int. 2012. 2012: 134905

6. Crowther M, Cuker A. How can we reverse bleeding in patients on direct oral anticoagulants?. Kardiol Pol. 2019. 77: 3-11

7. Crowther MA, Warkentin TE. Bleeding risk and the management of bleeding complications in patients undergoing anticoagulant therapy: Focus on new anticoagulant agents. Blood. 2008. 111: 4871-9

8. Cuker A, Burnett A, Triller D, Crowther M, Ansell J, Van Cott EM. Reversal of direct oral anticoagulants: Guidance from the anticoagulation forum. Am J Hematol. 2019. 94: 697-709

9. Frontera JA, Lewin JJ, Rabinstein AA, Aisiku IP, Alexandrov AW, Cook AM. Guideline for reversal of antithrombotics in intracranial hemorrhage: A statement for healthcare professionals from the neurocritical care society and society of critical care medicine. Neurocrit Care. 2016. 24: 6-46

10. Groen RJ, Groenewegen HJ, August H, van Alphen M, Hoogland PV. Morphology of the human internal vertebral venous plexus: A cadaver study after intravenous araldite CY 221 Injection. Anat Rec. 1997. 249: 285-94

11. Hernandez-Juarez J, Espejo-Godinez HG, Mancilla-Padilla R, Hernandez-Lopez JR, Moreno JA, Majluf-Cruz K. Effects of rivaroxaban on platelet aggregation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2020. 75: 180-4

12. Jeong YH, Oh JW, Cho S. Clinical outcome of acute epidural hematoma in Korea: Preliminary report of 285 cases registered in the Korean trauma data bank system. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2016. 12: 47-54

13. Jiang H, Jiang Y, Ma H, Zeng H, Lv J. Effects of rivaroxaban and warfarin on the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol. 2021. 44: 1208-15

14. Kakkos SK, Kirkilesis GI, Tsolakis IA. Editor’s choice-efficacy and safety of the new oral anticoagulants dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban in the treatment and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis of phase III trials. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014. 48: 565-75

15. Kim BG, Yoon SM, Bae HG, Yun IG. Spontaneous intracranial epidural hematoma originating from dural metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2010. 48: 166-9

16. Kubitza D, Becka M, Voith B, Zuehlsdorf M, Wensing G. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of single doses of BAY 59-7939, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005. 78: 412-21

17. Lapadula G, Caporlingua F, Paolini S, Missori P, Domenicucci M. Epidural hematoma with detachment of the dural sinuses. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2014. 5: 191-4

18. Liew A, Eikelboom JW, O’Donnell M, Hart RG. Assessment of anticoagulation intensity and management of bleeding with old and new oral anticoagulants. Can J Cardiol. 2013. 29: S34-44

19. Lu G, Deguzman FR, Hollenbach SJ, Karbarz MJ, Abe K, Lee G. A specific antidote for reversal of anticoagulation by direct and indirect inhibitors of coagulation factor Xa. Nat Med. 2013. 19: 446-51

20. Majeed A, Kim YK, Roberts RS, Holmström M, Schulman S. Optimal timing of resumption of warfarin after intracranial hemorrhage. Stroke. 2010. 41: 2860-6

21. Marcoux J, Bracco D, Saluja RS. Temporal delays in trauma craniotomies. J Neurosurg. 2016. 125: 642-7

22. Maurice-Szamburski A, Graillon T, Bruder N. Favorable outcome after a subdural hematoma treated with feiba in a 77-year-old patient treated by rivaroxaban. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2014. 26: 183

23. Montemurro N, Santoro G, Marani W, Petrella G. Posttraumatic synchronous double acute epidural hematomas: Two craniotomies, single skin incision. Surg Neurol Int. 2020. 11: 435

24. Moon JY, Bae GH, Jung J, Shin DH. Restarting anticoagulant therapy after intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation: A nationwide retrospective cohort study. Int J Cardiol Hear Vasc. 2022. 40: 101037

25. Nieswandt B, Pleines I, Bender M. Platelet adhesion and activation mechanisms in arterial thrombosis and ischaemic stroke. J Thromb Haemost. 2011. 9: 92-104

26. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011. 365: 883-91

27. Pujari R, Hutchinson PJ, Kolias AG. Surgical management of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg Sci. 2018. 62: 584-92

28. Raeouf A, Goyal S, van Horne N, Traylor J. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma secondary to rivaroxaban use in a patient with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Cureus. 2020. 12: e10417

29. Rahimizadeh A, Malekmohammadi Z, Williamson WL, Rahimizadeh S, Amirzadeh M, Asgari N. Rivaroxaban-induced acute cervical spine epidural hematoma: Report of a case and review. Surg Neurol Int. 2019. 10: 210

30. Ray WA, Chung CP, Stein CM, Smalley W, Zimmerman E, Dupont WD. Association of rivaroxaban vs apixaban with major ischemic or hemorrhagic events in patients with atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2021. 326: 2395-404

31. 32. Scaglione F. New oral anticoagulants: Comparative pharmacology with Vitamin K antagonists. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2013. 52: 69-82 33. Shin S, Kang H, Lee JW, Gyun KH, Choi ES. Epidural hematoma after total knee arthroplasty in a patient receiving rivaroxaban: A case report. Anesth Pain Med. 2019. 14: 102-5 34. Steiner T, Böhm M, Dichgans M, Diener HC, Ell C, Endres M. Recommendations for the emergency management of complications associated with the new direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), apixaban, dabigatran and rivaroxaban. Clin Res Cardiol. 2013. 102: 399-412 35. Trujillo T, Dobesh PP. Clinical use of rivaroxaban: Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic rationale for dosing regimens in different indications. Drugs. 2014. 74: 1587-603 36. Van Dongen CJ, Prandoni P, Frulla M, Marchiori A, Prins MH, Hutten BA. Relation between quality of anticoagulant treatment and the development of the postthrombotic syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2005. 3: 939-42 37. Yeh CH, Hogg K, Weitz JI. Overview of the new oral anticoagulants: Opportunities and challenges. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015. 35: 1056-65 38. Zaarour M, Hassan S, Thumallapally N, Dai Q. Rivaroxaban-induced nontraumatic spinal subdural hematoma: An uncommon yet life-threatening complication. Case Rep Hematol. 2015. 2015: 275380