- Department of Neurosurgery, Careggi Hospital, Florence, Italy

- Department of Neurosurgery, Le Scotte Hospital, Siena

- School of Neurosurgery, University of Florence, Florence, Italy

Correspondence Address:

Giovanni Muscas

Department of Neurosurgery, Le Scotte Hospital, Siena

DOI:10.4103/sni.sni_131_17

Copyright: © 2017 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Giovanni Muscas, Francesco Iacoangeli, Laura Lippa, Biagio R. Carangelo. Spontaneous rupture of a secondary pituitary abscess causing acute meningoencephalitis: Case report and literature review. 09-Aug-2017;8:177

How to cite this URL: Giovanni Muscas, Francesco Iacoangeli, Laura Lippa, Biagio R. Carangelo. Spontaneous rupture of a secondary pituitary abscess causing acute meningoencephalitis: Case report and literature review. 09-Aug-2017;8:177. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/spontaneous-rupture-of-a-secondary-pituitary-abscess-causing-acute-meningoencephalitis-case-report-and-literature-review/

Abstract

Background:Pituitary abscess (PA) is an uncommon finding that is rarely diagnosed preoperatively. If not properly treated it is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. Nowadays standard diagnostic procedures allow early detection and successful treatment of this lesion in a high number of cases and mortality has been significantly reduced in recent years. PA arising de novo in a healthy gland are defined as primary, whereas those complicating a pre-existing disease of the hypophysis are called secondary abscesses.

Case Description:We present a case of a secondary PA mimicking a large pituitary adenoma extending in the nasal cavity, which was wrongly diagnosed as such. The abscess showed an unexpected evolution in 48 h from presentation due to a sudden, extensive intracranial leakage of pus.

Conclusions:To our knowledge, it is rare to find PA showing a rapid evolution like this, and in the literature only one previous case of a PA not reaching medical or surgical therapy was reported. In that case, hypothalamus involvement was identified as the cause of death. This should be the first case reported of a spontaneous PA rupture causing acute meningoencephalitis. Along with a short review of the literature on the major features of PA, we also tried to identify some features which could be supportive of a diagnosis of secondary PA.

Keywords: Adenoma, brain abscess, meningoencephalitis, pituitary abscess, pituitary neoplasm

INTRODUCTION

Pituitary abscess (PA) represents 0.2–1.1% of all surgically treated pituitary lesions.[

PA can grow on a normal gland (70%) or complicate diseases of the hypophysis (pituitary adenomas, Rathke's cleft cysts, craniopharyngiomas).[

In many cases no microorganism can be isolated from cultures.[

PA has unspecific clinical and radiological features[

Here, we present a case of unexpected evolution with fatal outcome of a PA mimicking a partially cystic pituitary adenoma. The reason for this evolution was identified during surgery, when we were able to visualize a large subdural collection of pus.

According to a recent systematic review of the literature,[

In none of them a spontaneous abscess rupture with a large subdural pus diffusion causing a meningoencephalitis was identified as the cause of death.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 47-year-old woman with a 2-day history of headache and blurred vision was referred to our department from a peripheral hospital. A CT scan of the skull had showed a large mass arising from the sella, eroding the bony structures and invading the nasal cavity.

On admission she presented Glasgow coma scale (GCS) 15, afebrile. Neurological examination showed no alterations. Visual field was intact. Body mass index (BMI) was 28.2, medical history included mild psoriasis, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), cholelithiasis, no relevant infections except in her infancy, and no previous surgeries. She did not take any routine medications. She was the mother of two children and had regular menses. Blood pressure and heart rate were within normal limits. Blood test showed microcromic microcytic anemia, reticulocytosis [hemoglobin (Hb): 8.6g/dL; hematocrit (HCT): 27.8%; mean cell volume (MCV): 64.5; mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH): 20 pg; mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC): 30.9 g/dL; red blood cell distribution width (RDW): 20.2 %)]. Leucocytes count and inflammatory indexes where within normal limits. Hormone blood concentrations were normal except for a slight decrease in thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (0.238 μU/mL and 0.6 mU/mL); β-17-estradiol was 35.8 pg/mL. Urine osmolality was normal.

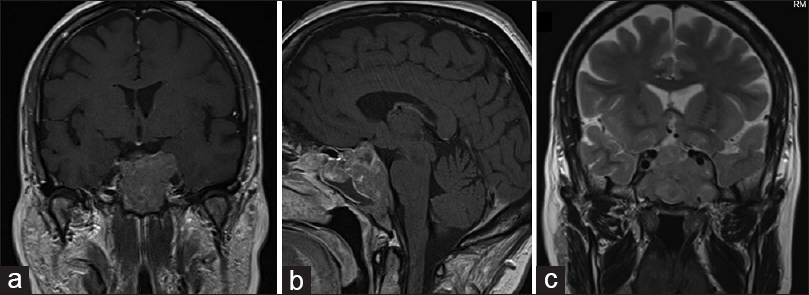

An enhanced MRI [Figure

Figure 1

(a) Pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium. T1-weighted coronal section showing a large enhancing sellar lesion with suprasellar extension, impinging the chiasm and abutting both cavernous sinuses. (b) T1-weighted sagittal section with gadolinium showing a mixed solid-cystic component of the tumor. The chiasm is dislocated upwards (c) T2-weighted coronal scan showing a mixed solid-cystic components of the lesion

According to the clinical and radiological data, a large pituitary adenoma with a mixed solid/cystic consistence was diagnosed. The patient was admitted and scheduled for surgery the same week. Her headache was treated with pain medications. She complained of no vision problems.

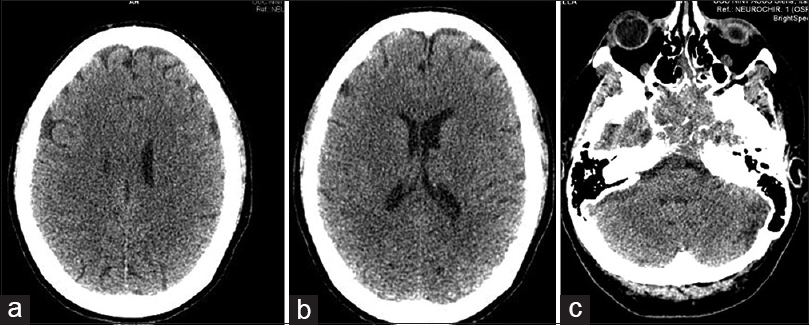

Forty eight hours after onset of symptoms, her headache suddenly worsened and she rapidly developed gaze palsy and nuchal rigidity. GCS fell from 15 to 6 (E:1, V:2; M:3). After an emergency CT showed no parenchymal infarction, extra-axial bleeding, fluid collection, or ischemia [

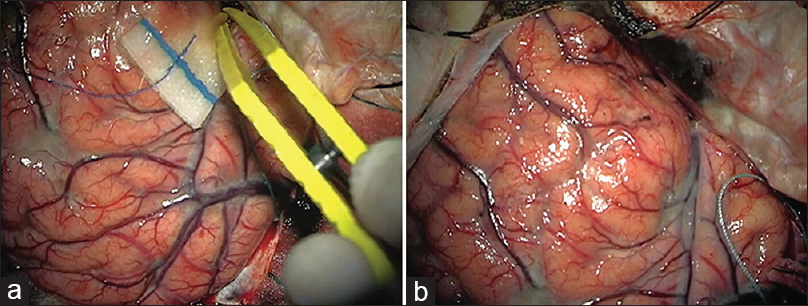

After opening the dura mater, the brain was swelling, with a considerable amount of dense pus covering the brain surface [Figure

The patient was subsequently taken to the intensive care unit (ICU), but she did not recover and died a few days later.

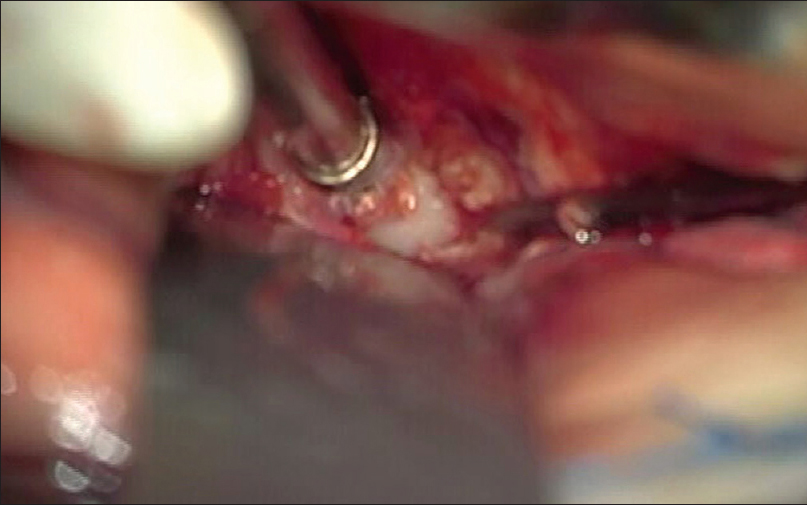

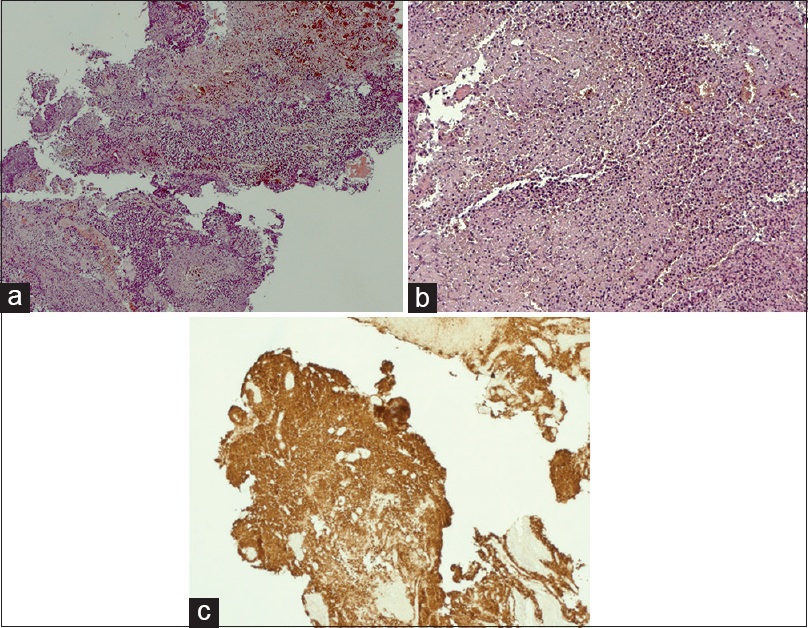

The pathological analysis of the intraoperative material confirmed a nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma with chronic inflammation and necrosis [Figure

DISCUSSION

In this case a secondary PA was misdiagnosed as a cystic pituitary adenoma. The patient had no history of infections or metabolic diseases, or any signs or symptoms of infections. Her clinical condition worsened rapidly and unexpectedly in less than 2 days. During surgery a large amount of pus was found intradurally. An abscess was found within the tumor, which was confirmed to be an adenoma. Death due to PA is considered rare nowadays, with a mortality of 4.5%.[

We explained this finding as the consequence of a sudden spontaneous PA rupture. Pus leakage from a PA has been hypothesized as a possible cause of recurrent meningitis[

Since its first descriptions (Heslop, 1848),[

Predisposing factors are infections (sinusitis, cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis, tooth infections, osteomyelitis, endocarditis), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage, previous surgeries or local radiotherapies, and immunocompromise.[

A proposed classification based on the etiology identified four groups:[

In secondary cases without previous infections the origin can be caused by direct tumor invasion of extracranial structures or by tumor necrosis with impairment of local immunity.[

No microorganism can be isolated in approximately 50% of cases (so called primary abscess).[

Clinically, they manifest with headache, which is the most common symptom and can be the only presenting, visual disturbances, hormonal disfunctions, and cranial nerve disabilities.[

On CT, PA appears as a cystic lesions with peripheral ring enhancement.[

Notwithstanding this, colliquative or cystic adenomas, pituitary apoplexy,[

PAs are often misdiagnosed preoperatively as cystic pituitary adenomas.[

Zhang[

Moreover, the peripheral enhancement observed in normal tissue surrounding an adenoma is usually thicker than dose related to a PA.[

The definitive diagnosis is made on direct vision and on histology showing acute or chronic inflammation with neutrophils or monocytes and lymphocytes.[

If an abscess is diagnosed or suspected, antibiotic therapy should be started and surgical drainage planned as soon as possible. Prompt therapy can reduce mortality to less than 10%.[

There is no consensus on the duration of the antibiotic therapy: Yet most cases were successful after a 4–6-week course of treatment and some patients were treated with antibiotics alone.[

A life-long hormonal replacement can be necessary,[

PAs can be fatal and, according to the literature, death can be caused by pituitary apoplexy, hypothalamic involvement, complications of sepsis, or unknown causes.[

Our case represented an acute purulent meningoencephalitis caused by the spontaneous rupture of a secondary PA. To our knowledge, this occurrence has never been observed. This patient had showed no fever or signs of infections and her medical history showed no relevant pathologies. The sudden worsening of this case is peculiar and only one previous case with similar evolution was described.[

CONCLUSIONS

We describe a possible complication of PA. As far as we know, this evolution has never been described. PA can undergo spontaneous rupture and cause acute meningoencephalitis.

This case also raises some important questions on the opportunity to consider pituitary abscess as a possible diagnosis in mixed cystic/solid sellar lesions in order to establish proper therapies, avoiding fatal outcomes. A large sellar lesion extending over the anatomical boundaries of the skull base and showing a cystic component might have undergone a superinfection and harbor a secondary PA.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Agyei JO, Lipinski LJ, Leonardo J. Case Report of a Primary Pituitary Abscess and Systematic Literature Review of Pituitary Abscess with a Focus on Patient Outcomes. World Neurosurg. 2017. 101: 76-92

2. Altas M, Serefhan A, Silav G, Cerci A, Coskun KK, Elmaci I. Diagnosis and management of pituitary abscess: A case series and review of the literature. Turk Neurosurg. 2013. 23: 611-6

3. Ciappetta P, Calace A, D’Urso PI, De Candia N. Endoscopic treatment of pituitary abscess: Two case reports and literature review. Neurosurg Rev. 2008. 31: 237-46

4. Dalan R, Leow MKS. Pituitary abscess: Our experience with a case and a review of the literature. Pituitary. 2008. 11: 299-306

5. Dutta P, Bhansali A, Singh P, Kotwal N, Pathak A, Kumar Y. Pituitary abscess: Report of four cases and review of literature. Pituitary. 2006. 9: 267-73

6. Gill M, Pathak HC, Singh P, Garg M. Recurrent Primary Pituitary Abscess. World J Endocr Surg. 2012. 4: 108-11

7. Hatiboglu MA, Iplikcioglu AC, Ozcan D. Abscess formation within invasive pituitary adenoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2006. 13: 774-7

8. Hazra S, Acharyya S, Acharyya K. Primary pituitary abscess in an adolescent boy: A rare occurrence. Case Reports 2012. 2012. p.

9. Jaiswal AK, Mahapatra AK, Sharma MC. Pituitary abscess associated with prolactinoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2004. 11: 533-4

10. Karagiannis AKA, Dimitropoulou F, Papatheodorou A, Lyra S, Seretis A, Vryonidou A. Pituitary abscess: A case report and review of the literature. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep 2016. 2016. p.

11. Kuge A, Sato S, Takemura S, Sakurada K, Kondo R, Kayama T. Abscess formation associated with pituitary adenoma: A case report: Changes in the MRI appearance of pituitary adenoma before and after abscess formation. Surg Neurol Int. 2011. 2: 3-

12. Liu F, Li G, Yao Y, Yang Y, Ma W, Li Y. Diagnosis and management of pituitary abscess: Experiences from 33 cases. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011. 74: 79-88

13. Meftah A, Moumen A, Eljadi H, Guerboub AA, Elmoussaoui S, Belmejdoub G. Pituitary abscess simulating a pituitary adenoma. Presse Med. 2016. 45: 602-4

14. Safaee MM, Blevins L, Liverman CS, Theodosopoulos PV. Abscess Formation in a Nonfunctioning Pituitary Adenoma. World Neurosurg. 2016. 90: 1-4

15. Su YH, Chen Y, Tseng SH. Pituitary abscess. J Clin Neurosci. 2006. 13: 1038-41

16. Takahashi T, Shibata S, Ito K, Ito S, Tanaka M, Suzuki S. Neuroimaging appearance of pituitary abscess complicated with close inflammatory lesions-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1998. 38: 51-4

17. Vates GE, Berger MS, Wilson CB. Diagnosis and management of pituitary abscess: A review of twenty-four cases. J Neurosurg. 2001. 95: 233-41

18. Walia R, Bhansali A, Dutta P, Shanmugasundar G, Mukherjee KK, Upreti V. An uncommon cause of recurrent pyogenic meningitis: Pituitary abscess. BMJ Case Rep 2010. 2010. p. 2-5

19. Zhang X, Sun J, Shen M, Shou X, Qiu H, Qiao N. Diagnosis and minimally invasive surgery for the pituitary abscess: A review of twenty nine cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012. 114: 957-61