- Department of Neurosurgery, National Brain Aneurysm and Tumor Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States

Correspondence Address:

Eric S. Nussbaum, Department of Neurosurgery, National Brain Aneurysm and Tumor Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1100_2024

Copyright: © 2025 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Frank M. Nussbaum, Eric S. Nussbaum. Subdural hematoma complicated by seizures and prolonged neurological decline: An ethical management dilemma. 07-Mar-2025;16:84

How to cite this URL: Frank M. Nussbaum, Eric S. Nussbaum. Subdural hematoma complicated by seizures and prolonged neurological decline: An ethical management dilemma. 07-Mar-2025;16:84. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=13428

Abstract

BackgroundNeurosurgeons often face life-and-death decisions that may present serious ethical questions. Some of the most challenging situations arise when members of the care team disagree regarding the most appropriate management plan.

Case DescriptionWe present the case of an older woman with a subdural hematoma and postoperative seizures resulting in prolonged neurological decline. This case highlights an ethical dilemma as part of a series of cases that will be described in coming issues of SNI.

ConclusionReaders are invited to submit comments and observations, which may be published as part of an ongoing conversation regarding such ethical concerns.

Keywords: Ethics, Neurosurgery, Seizure, Subdural hematoma

INTRODUCTION

Neurosurgeons are frequently called on to evaluate patients presenting with acute neurological injury who are in poor condition. The decision of whether or not to operate may be straightforward, for example, in the case of an elderly patient with a clear advance directive who has suffered a severe head injury resulting in minimal remaining brainstem function. On the other hand, the decision can be more complicated in which case the limitation of care may carry significant ethical considerations. The present case involves an older woman with a subdural hematoma (SDH) and seizure activity that resulted in a situation in which the patient was in poor neurological condition but also had the potential for meaningful recovery. This case created controversy within our care team and is described to initiate a conversation among readers.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 79-year-old woman presented to her local family physician with 2 weeks of headaches and intermittent numbness involving the left hand and face. The patient reported having fallen in the shower approximately one month earlier. Past medical history was significant for breast cancer, which had been treated successfully 15 years earlier, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and atrial fibrillation. Her medications included propranolol, a statin, and warfarin.

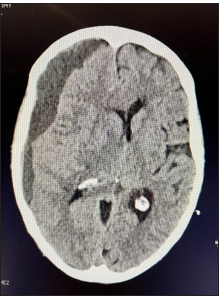

A non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the head revealed a subacute/chronic SDH measuring 13 mm in maximal thickness, resulting in a 1 cm midline shift. The patient was sent to the emergency department for further evaluation.

On examination, the patient was alert and oriented, complaining of a significant headache. She had mild weakness in the left upper extremity. She was admitted to the hospital for observation, and the neurosurgical service was consulted.

On arrival on the floor, the patient suffered a generalized seizure. She was treated with Ativan, loaded with levetiracetam, and transferred to the intensive care unit. Given her depressed level of consciousness, the patient was intubated for airway protection. A follow-up CT scan was obtained, demonstrating modest expansion of the SDH with increased midline shift, and the patient was brought to the operating room on an emergency basis [

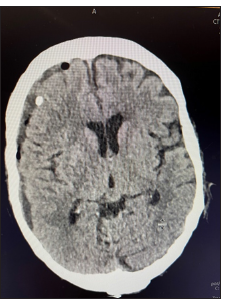

Burr-hole evacuation of the SDH was performed without difficulty, and a subdural drain was left in place. Postoperatively, the patient was returned to the intensive care unit, where she remained intubated overnight. The following morning, a CT scan showed adequate evacuation of the SDH with a small amount of air within the subdural space [

The patient lived alone and had no spouse or children. She had an older sister who lived out of the country, and who could not be reached. There was no evidence of an advance directive. At this point, a debate occurred within the care team regarding the appropriate management of the patient. Based on the patient’s age and a perceived poor prognosis, multiple intensivists, nurses, and neurologists recommended that support be withdrawn. Other members of the team felt that there was potential for a favorable recovery and that aggressive care, therefore, should be continued. A decision was made.

Ethical debate

Treatment options were actively discussed by members of the care team ranging from comfort care measures to fully aggressive treatment. In the absence of an immediate relative or anyone with a healthcare power of attorney, there was no one to provide insight into the patient’s wishes. There was no advance care directive available. Before her first seizure, the patient had talked about her willingness to undergo surgical evacuation of her hematoma with the hospitalist physician. There had been no conversation regarding her wishes in the event of a serious surgical complication or other adverse event. Before hospital admission, the patient was living independently, was driving herself, and was meeting with friends several times per week outside her home.

Arguing to limit care, multiple members of the care team felt that given the patient’s age, compromised neurological status, and potential for permanent neurological deficit; there was ample reason to move toward comfort measures. It was argued that most individuals would not wish to be moved to a nursing care facility and live with new and potentially significant neurological deficits.

Opposing opinions suggested that there was no reason to think the patient could not make a complete recovery; therefore, it was considered “unethical” to limit care at this point. Without direct input instructing the care team to limit care measures based on strict instructions from the patient, it was argued that full care should be provided.

The hospital ethics committee was consulted. They determined that there was no clear, correct avenue based on ethical concerns and returned the decision to the care team to be adjudicated based on the expected prognosis, which remained a debated issue. The possibility of approaching a judge to appoint an independent health care proxy was suggested.

Case description continued

A decision was made to continue full care. After 48 h, the patient remained deeply sedated, and magnetic resonance imaging was performed, revealing no obvious injury to the brain. At 1 week, the patient had not regained consciousness, and the initial debate continued. The same arguments were made, with some members of the care team arguing for comfort measures while others suggested that full care be continued. An application for a healthcare proxy was made to the court system, but due to scheduling delays, a decision had to be made. Multiple attempts were made to contact the sister, but her phone was disconnected, and she could not be located. The patient’s friends visited her in the hospital, but they were not helpful in terms of determining what her wishes would have been. At this point, a tracheostomy and jejunostomy were performed, and the patient was sent to a skilled nursing facility.

Three months later, the patient returned to the neurosurgery clinic for follow-up. She was neurologically intact and had no memory of her hospitalization. Her tracheostomy and jejunostomy incisions were well-healed. She was appreciative that the team had “saved her life” and was living at home independently. She was continued on an anticonvulsant for 12 months, at which time an EEG was normal, and the medication was discontinued.

DISCUSSION

Won et al. reviewed 375 patients with chronic SDH and found that acute symptomatic seizures occurred in 15.2% of cases and were associated with a significantly more unfavorable outcome at discharge and at the time of delayed follow-up.[

This case raised multiple ethical issues for the care team. Absent clear instructions from the patient or a representative, the team was left to substitute their own best judgment in this complex setting. Because members of the team felt differently about how they would have wanted to be managed were they or a loved one in this setting, differing opinions emerged. Ultimately, the final decision was based on the potential for a complete recovery, taking into account the imaging findings.

Luce and White addressed the challenge of inadequate communication in creating conflict regarding end-of-life care in elderly patients, noting that such conflict within the care team can result in inappropriate limitation of care in such cases.[

This case raised several complex issues that challenge physicians practicing today. At the heart of these issues is the fundamental question of what is the true responsibility of a physician? When societal needs such as “rationing” of limited resources conflict with patient well-being, what is the physician’s responsibility? When completing medical school, most physicians take an oath to “first do no harm.” Does this mean that the physician must do whatever they can to save a patient’s life as was previously the accepted standard? At what financial cost is this no longer a reasonable approach? Furthermore, as questions regarding “quality of life” begin to take precedence in these conversations, who is left to judge what “quality of life” is meaningful enough to justify saving a person? Without the patient herself or her family to weigh in, as in our case, who is to make such Solomonic decisions? Finally, is advanced age alone a legitimate criterion for limiting care? Does this represent a form of “age discrimination” or a reasonable expression of scientific data linking advanced age to worse outcomes?

CONCLUSION

The present case is not presented to demonstrate that there was one correct decision. Instead, the presentation is meant to generate conversation and thought among readers who manage similarly complicated ethical situations on a regular basis. The importance of understanding patient wishes is highlighted. The authors emphasize the impact that the potential for complete recovery had in the decision-making part of this case.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Luce JM, White DB. The pressure to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining therapy from critically ill patients in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007. 175: 1104-8

2. Pacheco-Barrios N, Wadhwa A, Lau TS, Shutran M, Ogilvy CS. Risk factors associated with seizure after treatment of chronic subdural hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2024. 10: 1227

3. Rabinstein AA, Chung SY, Rudzinski LA, Lanzino G. Seizures after evacuation of subdural hematomas: Incidence, risk factors, and functional impact. J Neurosurg. 2010. 112: 455-60

4. Won SY, Dubinski D, Herrmann E, Cuca C, Strzelczyk A, Seifert V. Epileptic seizures in patients following surgical treatment of acute subdural hematoma-incidence, risk factors, patient outcome, and development of new scoring system for prophylactic antiepileptic treatment (GATE-24 score). World Neurosurg. 2017. 101: 416-24

5. Won SY, Dubinski D, Sautter L, Hattingen E, Seifert V, Rosenow F. Seizure and status epilepticus in chronic subdural hematoma. Acta Neurol Scand. 2019. 140: 194-203

6. Wu L, Guo X, Ou Y, Yu X, Zhu B, Li Y. Seizure after chronic subdural hematoma evacuation: Associated factors and effect on clinical outcome. Front Neurol. 2023. 14: 1190878