- Department of Neurosurgery, Showa University Hospital, Tokyo, Shinagawa-ku, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_405_2020

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Ryo Aiura, Masaki Matsumoto, Tohru Mizutani, Tatsuya Sugiyama, Daisuke Tanioka. Surgical clip occlusion of the V3 segment to prevent recurrent cerebral infarction associated with extracranial vertebral artery dissection: A case report. 15-Oct-2020;11:337

How to cite this URL: Ryo Aiura, Masaki Matsumoto, Tohru Mizutani, Tatsuya Sugiyama, Daisuke Tanioka. Surgical clip occlusion of the V3 segment to prevent recurrent cerebral infarction associated with extracranial vertebral artery dissection: A case report. 15-Oct-2020;11:337. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10324/

Abstract

Background: Recurrent cerebral infarction caused by traumatic extracranial vertebral artery dissection (EVAD) is treated medically and surgically. We report a case of EVAD that was treated using surgical clip occlusion of the V3 segment to prevent recurrent cerebral infarction.

Case Description: A 48-year-old man was admitted for a cerebral infarction caused by EVAD and was treated using 200 mg/day cilostazol. Afterward, the cerebral infarction recurred. Digital subtraction angiography revealed that initial severe stenosis of the VA ostium resulted in the final occlusion and that collateral vessels to the VA remained. We continued antiplatelet therapy, but the cerebral infarction recurred due to thromboembolism of the collateral vessels. Parent artery occlusion was planned. We exposed the V3 segment of the VA and clipped it to prevent the recurrence of cerebral infarction.

Conclusion: Surgical clip occlusion of the V3 segment was effective for treating recurrent cerebral infarction caused by traumatic EVAD that had remained an issue despite continuing medical therapy.

Keywords: Extracranial vertebral artery dissection, Occlusion clipping, Parent artery occlusion, V3 segment, Vertebral artery

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic extracranial vertebral artery dissection (EVAD) occurs less frequently than intracranial VA dissection but is recognized as an important cause of ischemic stroke. EVAD has occurred after spinal manoeuver[

CASE DESCRIPTION

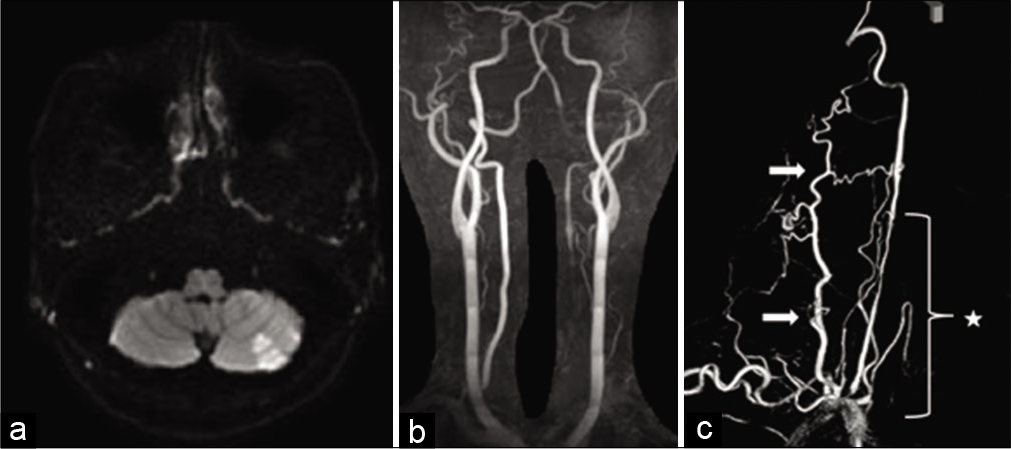

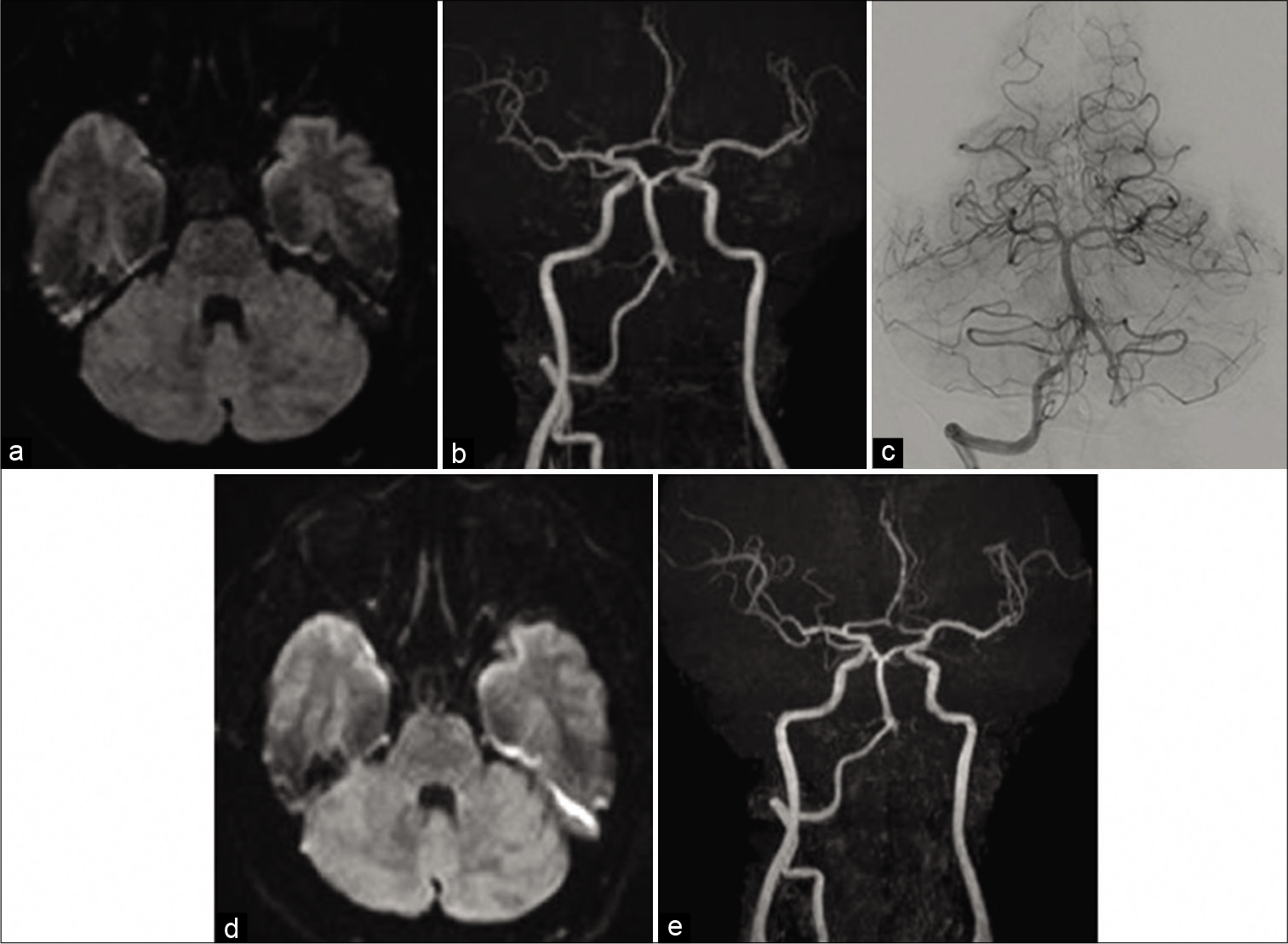

A 48-year-old man without connective tissue disease received a neck massage 2 years before being admitted to our hospital. Two months after the massage, he experienced vertigo and underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at another hospital. MRI revealed bilateral cerebellar infarction; however, its cause could not be determined. One year later, he received another neck massage and experienced vertigo. He visited the same hospital, and a second MRI revealed left cerebellar infarction and poor flow to the left VA [

Figure 1:

(a and b) Magnetic resonance images showing left cerebellar infarction and poor flow through the left vertebral artery. (c) Left subclavian artery angiography showing dissection from the vertebral artery ostium to the V2 segment, vertebral artery ostial stenosis (star), and collateral vessels (arrow).

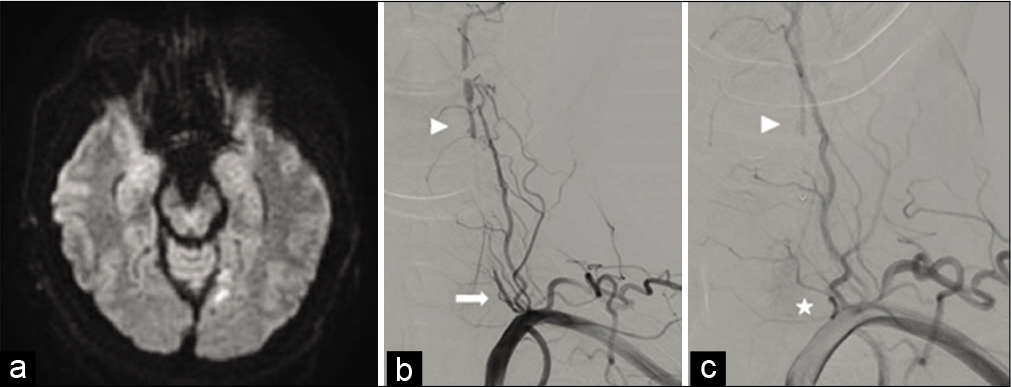

MRI findings in our hospital were similar to those obtained previously, and treatment with 200 mg/day cilostazol was continued while disease progression was observed. Five months later, he experienced right tinnitus and bilateral right hemianopia. MRI revealed left occipital lobe infarction [

Figure 2:

(a) Magnetic resonance images showing left occipital lobe infarction. (b and c) Left subclavian artery angiography showing vertebral artery flow from the collateral vessels (arrowhead), antegrade vertebral artery slow flow (arrow) from the vertebral artery ostium, and vertebral artery ostial occlusion (star).

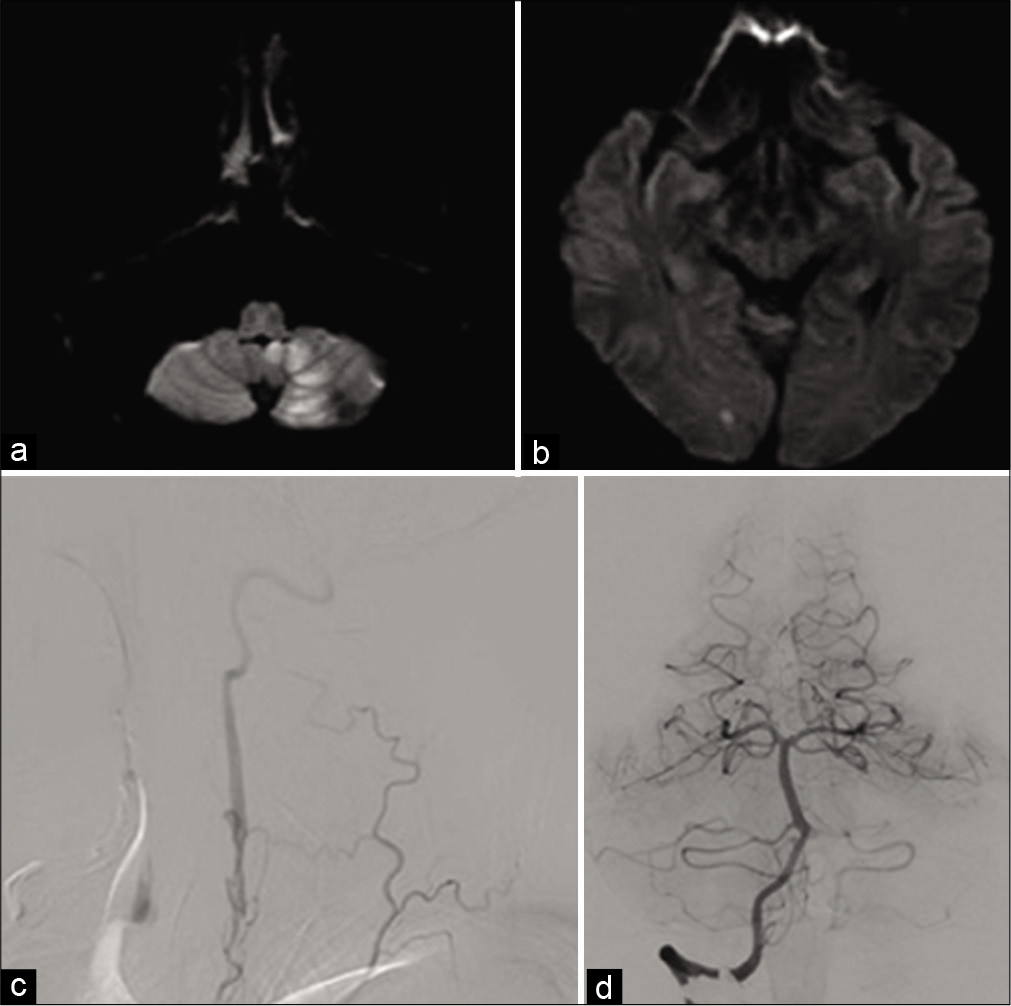

Figure 3:

(a and b) Magnetic resonance images showing left cerebellar infarction and right occipital lobe infarction. (c) Left subclavian artery angiography showing antegrade vertebral artery slow flow from the collateral vessels. (d) Right vertebral artery angiography showing the dominant right vertebral artery.

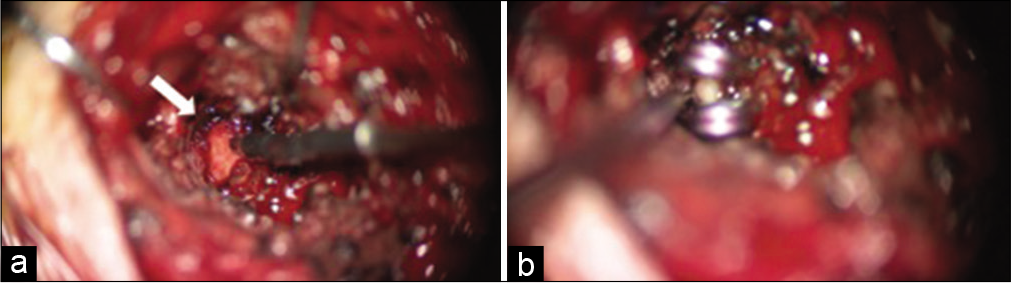

Surgical PAO was planned because the patient requested surgery and experienced repeated cerebral infarction despite the presence of occluding VA ostium and enhanced antiplatelet therapy. We decided to clip the V3 segment, which was more distally positioned than the collateral vessels. He underwent surgery in the supine position with his head turned to the right. This position enabled access to the VA with fewer skin incisions and with less damage to the VA venous plexus. We exposed the VA V3 segment after identifying the suboccipital triangle and confirmed VA blood flow with Doppler ultrasonography and indocyanine green video angiography. We clipped the VA using Yasargil Titanium Mini Clips (FT720T) [

There was no requirement for IRB/ethics committee approval. The patient provided consent for the publication of this case report.

DISCUSSION

Several studies reported traumatic EVAD occurrence postspinal manoeuvers, including chiropractic manipulation and neck rotation.[

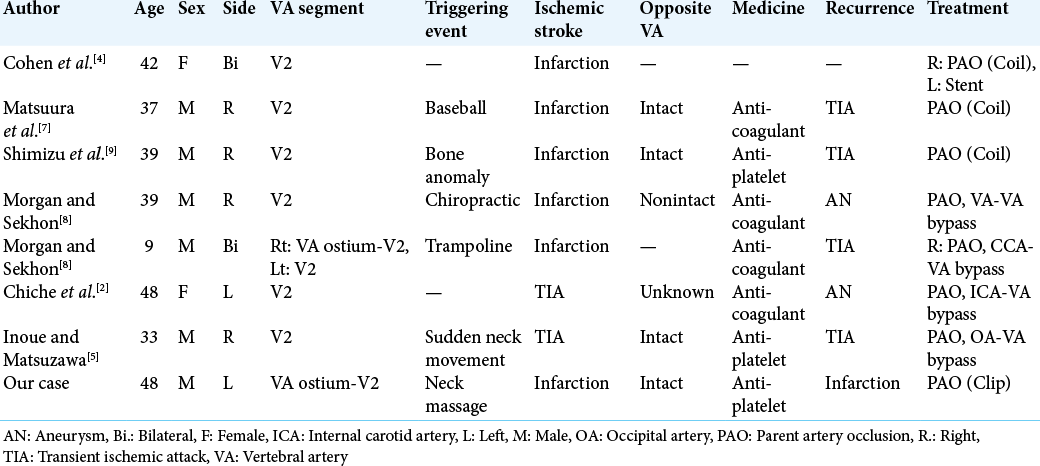

Seven cases of traumatic EVAD treated with PAO were reported [

For direct surgery, multiple studies have reported PAO with bypass,[

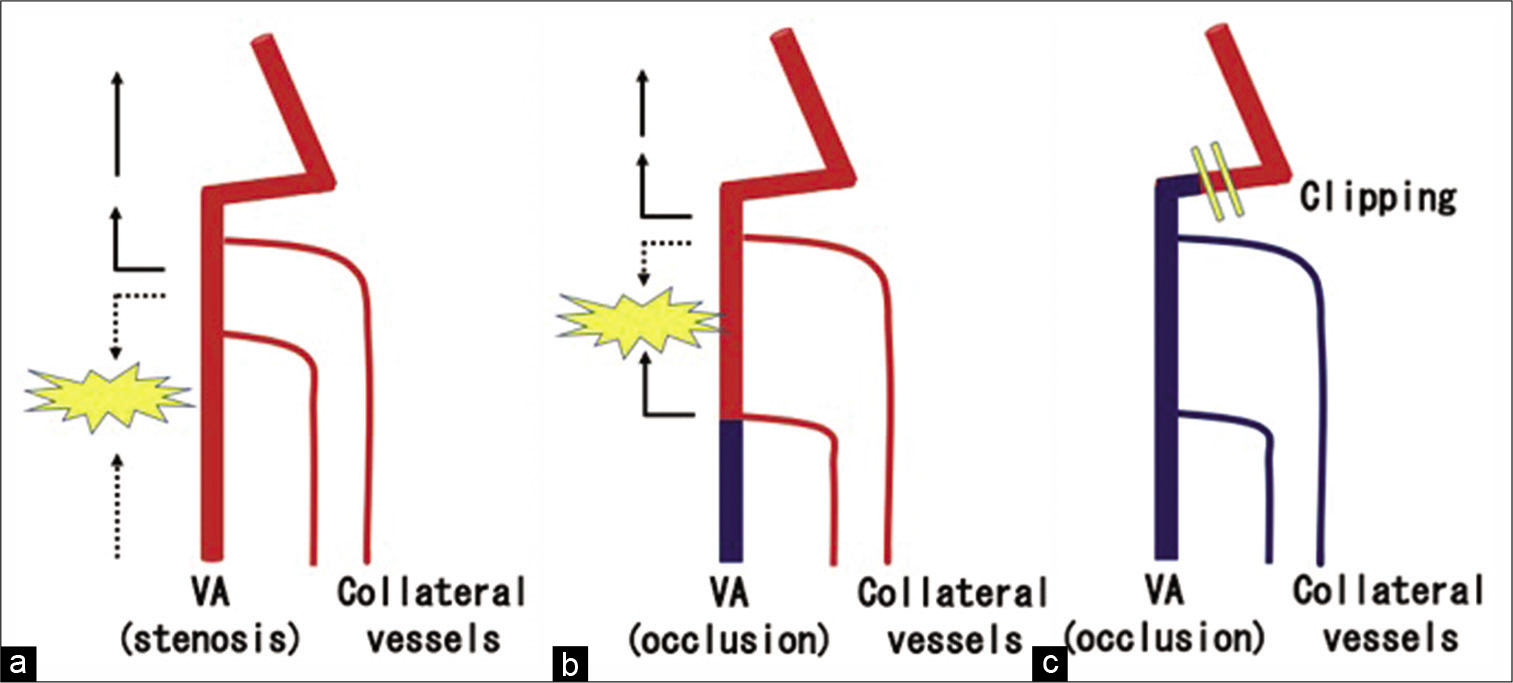

Our patient experienced cerebral infarction despite VA ostial occlusion. We expected that the thrombus was formed due to a collision that occurred between the flow of several collateral vessels at the VA. Therefore, we decided to clip the V3 segment, which was more distally positioned than the collateral vessels [

Figure 6:

(a) Severe vertebral artery ostial stenosis, antegrade vertebral artery flow, and retrograde flow from collateral vessels collided and produced thromboembolism. (b) Vertebral artery ostial occlusion and collision of flow from several collateral vessels resulted in thromboembolism. (c) After surgical clip occlusion.

Surgical occlusion using only clips is only recommended when the affected VA ostium is occluded and an approach through the VA ostium is not possible; therefore, surgical occlusion without reconstruction has limitations.

CONCLUSION

Surgical PAO is selected when patients experience recurrent ischemic strokes despite continuous medical therapy. Surgical occlusion using only clips without intracranial operation and craniotomy is a treatment option if the patient’s pathology permits.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Britt TB, Agarwal S.editors. Vertebral artery dissection. Stat Pearls. Treasure Island, FL: Stat Pearls Publishing; 2019. p.

2. Chiche L, Praquin B, Koskas F, Kieffer E. Spontaneous dissection of the extracranial vertebral artery: Indications and long-term outcome of surgical treatment. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005. 19: 5-10

3. Chowdhury MM, Sabbagh CN, Jackson D, Coughlin PA, Ghosh J. Antithrombotic treatment for acute extracranial carotid artery dissections: A meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015. 50: 148-56

4. Cohen JE, Gomori JM, Umansky F. Endovascular management of spontaneous bilateral symptomatic vertebral artery dissections. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003. 24: 2052-6

5. Inoue Y, Matsuzawa K. Occipital artery-to-vertebral artery bypass to stop transient ischemic attacks caused by traumatic vertebral artery dissection. World Neurosurg. 2019. 123: 64-6

6. Lau JT, Hunt JS, Bruner DI, Austin AL. Cervical artery dissection and choosing appropriate therapy. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2017. 1: 225-8

7. Matsuura D, Inatomi Y, Saeda H, Yonehara T, Fujioka S, Kai Y. Traumatic extracranial vertebral artery dissection treated with coil embolization-a case report. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2005. 45: 298-303

8. Morgan MK, Sekhon LH. Extracranial-intracranial saphenous vein bypass for carotid or vertebral artery dissections: A report of six cases. J Neurosurg. 1994. 80: 237-46

9. Shimizu S, Ishigaki T, Murata H, Kubo Y, Naoki T, Morooka Y. Vertebral artery dissection due to a bone anomaly of the superior facet of C6: A rare cause of embolic stroke. No Shinkei Geka. 2008. 36: 725-30

10. Turner RC, Lucke-World BP, Boo S, Rosen CL, Sedney CL. The potential dangers of neck manipulation and risk for dissection and devastating stroke: An illustrative case and review of the literature. Biomed Res Rev. 2018. 2: 10