- Department of Neurosurgery, Clinical Neurosciences Center, University of Utah, 175 N. Medical Drive East, Salt Lake City, Utah, 84132, USA

- Department of Radiology, University of Utah, 30 North 1900 East, Salt Lake City, Utah, 84132, USA

Correspondence Address:

Erica F. Bisson

Department of Neurosurgery, Clinical Neurosciences Center, University of Utah, 175 N. Medical Drive East, Salt Lake City, Utah, 84132, USA

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.163449

Copyright: © 2015 Ravindra VM. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.How to cite this article: Ravindra VM, Neil JA, Shah LM, Schmidt RH, Bisson EF. Surgical management of traumatic frontal sinus fractures: Case series from a single institution and literature review. Surg Neurol Int 24-Aug-2015;6:141

How to cite this URL: Ravindra VM, Neil JA, Shah LM, Schmidt RH, Bisson EF. Surgical management of traumatic frontal sinus fractures: Case series from a single institution and literature review. Surg Neurol Int 24-Aug-2015;6:141. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/surgical-management-of-traumatic-frontal-sinus-fractures-case-5/

Abstract

Background:Neurosurgeons are frequently involved in the management of patients with traumatic frontal sinus injury; however, management options and operative techniques can vary significantly. In this study, the authors review the current literature and retrospectively review the clinical series at a single tertiary referral center.

Methods:After Institutional Review Board approval, the medical records and computed tomographic (CT) imaging of patients whose traumatic frontal sinus fractures were treated surgically at the University of Utah were retrospectively reviewed. Demographic information, mechanism of injury, associated injuries, operative technique, and pattern of injury on CT were analyzed.

Results:Between 2000 and 2012, 33 patients underwent successful cranialization of the frontal sinus following traumatic injury. The material used to obliterate the sinus varied. No patients required immediate or delayed reoperation. Nasofrontal outflow tract obstruction, the importance of which has been emphasized in the plastic surgery literature, was apparent on either initial or retrospective review of the available CT imaging in 96%.

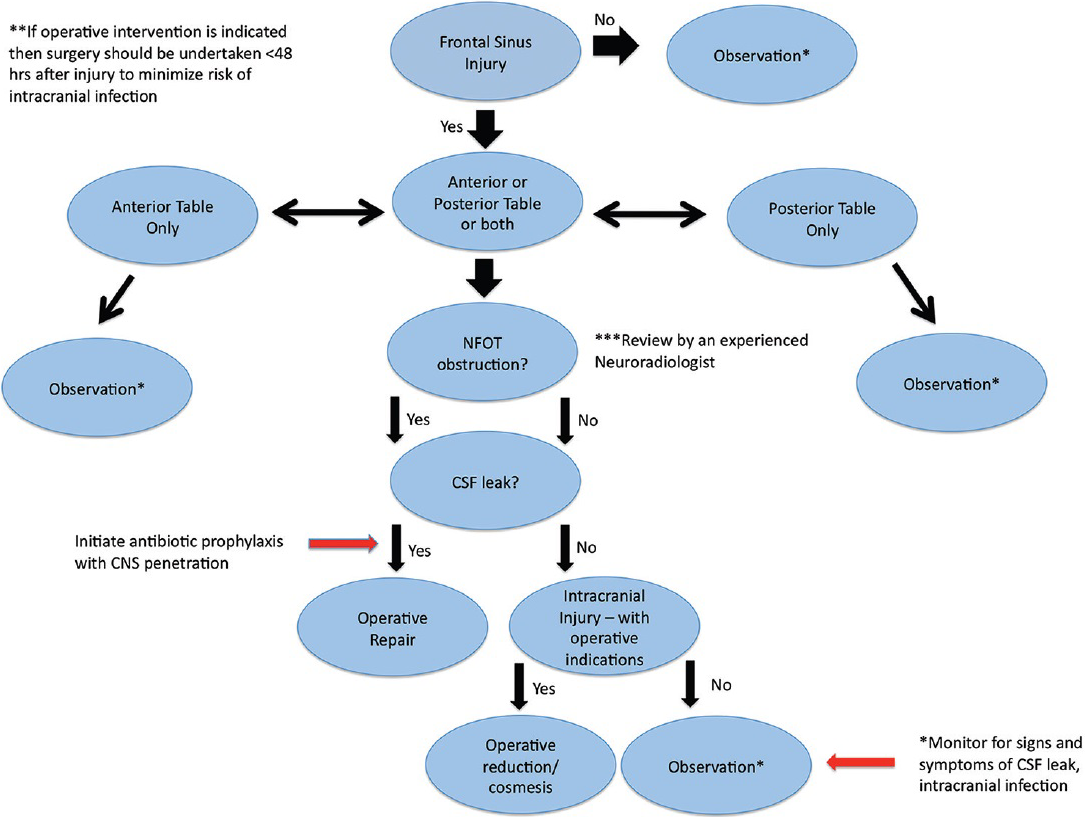

Conclusions:In this series, we successfully surgically treated 33 patients with frontal sinus fractures. The presence of cerebrospinal fluid leak, nasofrontal outflow tract injury, associated depressed skull fractures, and subsequent formation of communicating pathways and infection must be considered when constructing a treatment plan. The goals of treatment should be: (i) surgical repair of the defect and elimination of the conduit from the intracranial space to the outside and (ii) elimination of any cerebrospinal fluid pressure gradient that may develop across the surgical repair. We present a treatment algorithm focusing on the presence of nasofrontal outflow tract injury/obstruction, cosmetic deformity, and cerebrospinal fluid leak.

Keywords: Cranialization, frontal sinus, nasofrontal outflow tract, pericranial flap, trauma

INTRODUCTION

In trauma patients, frontal sinus fractures are common and account for 5–15% of all facial fractures. The most common cause of frontal sinus fractures is high-velocity blunt force trauma.[

Risk factors for postinjury complications have been analyzed in the plastic surgery literature. A large emphasis is placed on the presence or absence of nasofrontal outflow tract (NFOT) obstruction to determine whether surgical management should be undertaken [

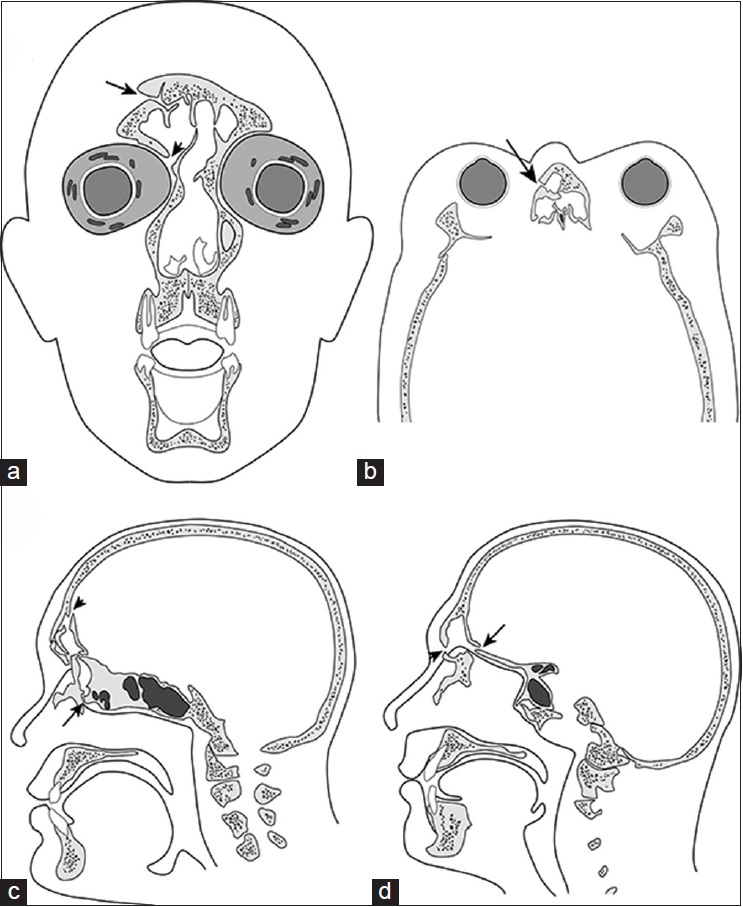

Figure 1

(a) Coronal illustration demonstrating a mildly displaced comminuted fracture of the right frontal sinus. The fracture involves the superior frontal sinus (arrow), and the displaced fracture fragment mildly narrows the egress of the right frontal sinus (arrowhead). (b) Axial drawing illustrating the typical nasofrontoethmoidal complex fracture involving the frontoethmoidal recess (arrow). (c) Sagittal drawing depicting displaced comminuted fractures of the frontal and anterior ethmoid sinuses (arrowhead), obstructing the drainage pathway of the frontal sinus (arrow). (d) Sagittal illustration showing a complex fracture of the frontal sinus involving the inner (arrow) and outer (arrowhead) tables. The type of injury increases the risk for cerebrospinal fluid leak and intracranial infection

We review the current literature and present a series of patients who underwent surgical repair for frontal sinus fractures from a single institution, propose a treatment algorithm to aid in the surgical management and treatment of these patients, and discuss techniques of cranialization of the frontal sinus, which involves complete removal of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus flush to the anterior skull base, complete removal of frontal sinus mucosa, and plugging of the nasofrontal ducts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After receiving Institutional Review Board approval, we queried our neurosurgical operative database to identify adult patients who had undergone surgical repair for frontal sinus fractures from 2000 to 2012. Patients who underwent frontal sinus repair secondary to nontraumatic injuries and patients treated nonsurgically were excluded from the series.

Hospital charts were reviewed to evaluate patient demographics, mechanism of injury, presence of CSF leak, number of days until operative intervention, and associated injuries. Imaging studies and radiology reports were reviewed and retrospectively reexamined to evaluate for NFOT obstruction. Operative reports were used to determine the presence of CSF leak, type of operative intervention performed, and material used to cranialize the sinus.

RESULTS

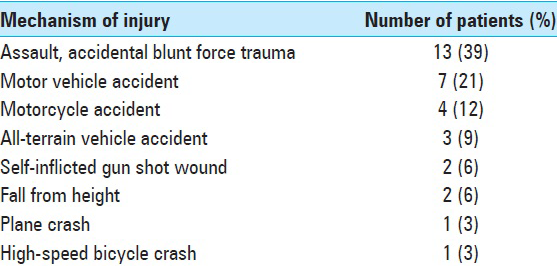

We identified 33 patients who underwent operative repair of frontal sinus fractures during the study period [

The most common mechanism of injury was blunt force trauma [

Eight (24%) patients had a CSF leak at their initial presentation, which manifested as persistent CSF rhinorrhea diagnosed upon history and physical with provocative testing. The initial radiology reports (available for 28 patients) indicated that 1 patient (3%) had NFOT obstruction; however, retrospective review of the available computed tomography (CT) images indicated that 27/28 (96%) demonstrated NFOT obstruction. Twenty-six of the patients had radiographic evidence of fractures through the anterior and posterior tables of the frontal sinus; one patient had a nasoethmoidal fracture with NFOT obstruction; and one patient underwent evacuation of an acute right frontal epidural hematoma with subsequent violation and cranialization of the ipsilateral frontal sinus. The average time to surgery was 4.6 ± 7.8 days after presentation. This time-to-surgery statistic excludes three patients from our series: Two of the patients were undergoing revision surgery after presenting 5 and 15 years after their initial traumatic injury, and one patient was transferred from an outside institution after a 25-day hospitalization period for the acute traumatic event.

All 33 patients underwent cranialization of the frontal sinus after the injury. Of the 26 (78%) patients with radiographic evidence of frontal sinus fractures, 15 had greater than full-width displacement through the sinus and 11 had less than full-width displacement.

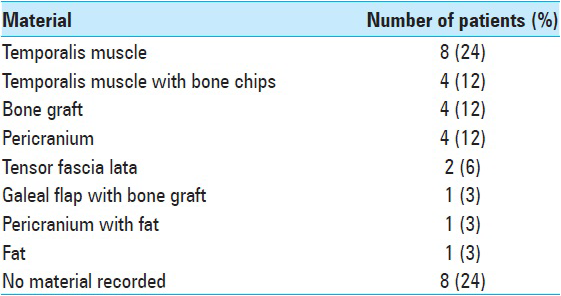

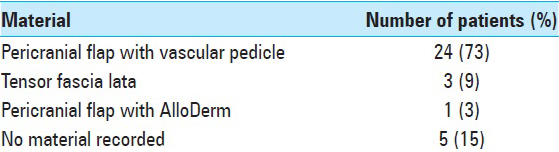

The material that was used to pack the sinus and obliterate the nasofrontal duct varied among the 25 patients [

Overall, 22/33 (67%) patients had associated intracranial injuries classified radiographically as either intraparenchymal hemorrhage, cerebral contusion, traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage, epidural hematoma, or subdural hematoma. No patient required immediate reoperation or had delayed abscess or mucocele formation requiring surgery.

Illustrative cases

Case 1

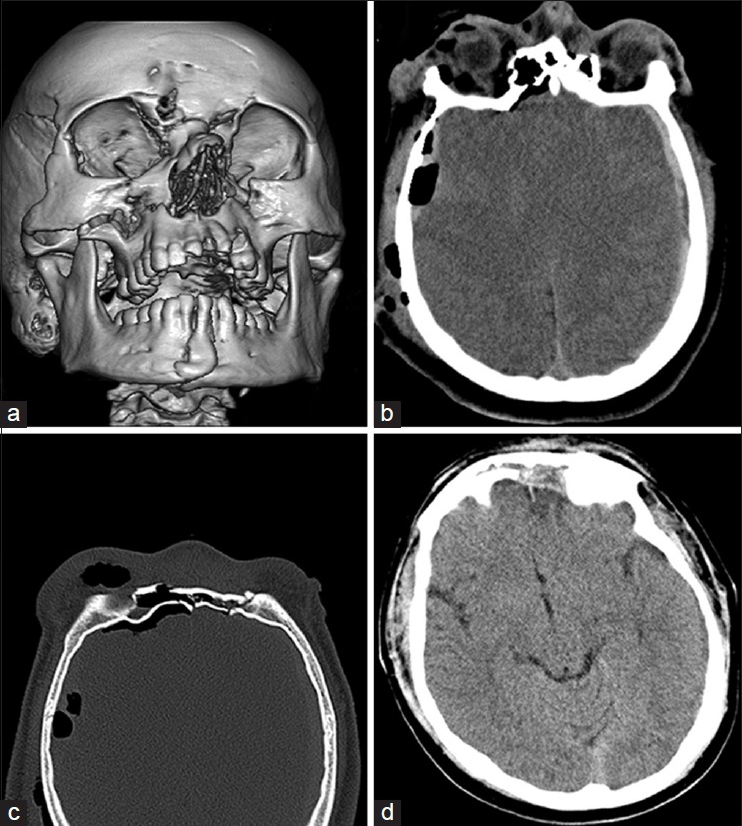

A 17-year-old male presented with multiple stab wounds and extensive facial trauma. A facial CT three-dimensional surface rendering showed the extent of the facial trauma and injury pattern [

Figure 2

Case 1. (a) Three-dimensional recontruction showing the injury pattern and extensive facial trauma suffered by this 17-year-old male. (b) Axial head computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating bilateral subdural hematomas with associated cerebral edema and moderate amount of pneumocephalus. (c) Axial CT scan of the facial bones displaying a comminuted fracture through the frontal sinus with disruption of the anterior and posterior tables. The degree of displacement is less than full width. There is associated nasofrontal outflow tract obstruction and moderate right frontal pneumocephalus. (d) Postoperative axial head CT scan demonstrating interval resolution of the subdural fluid collections as well as successful cranialization of the frontal sinus

Case 2

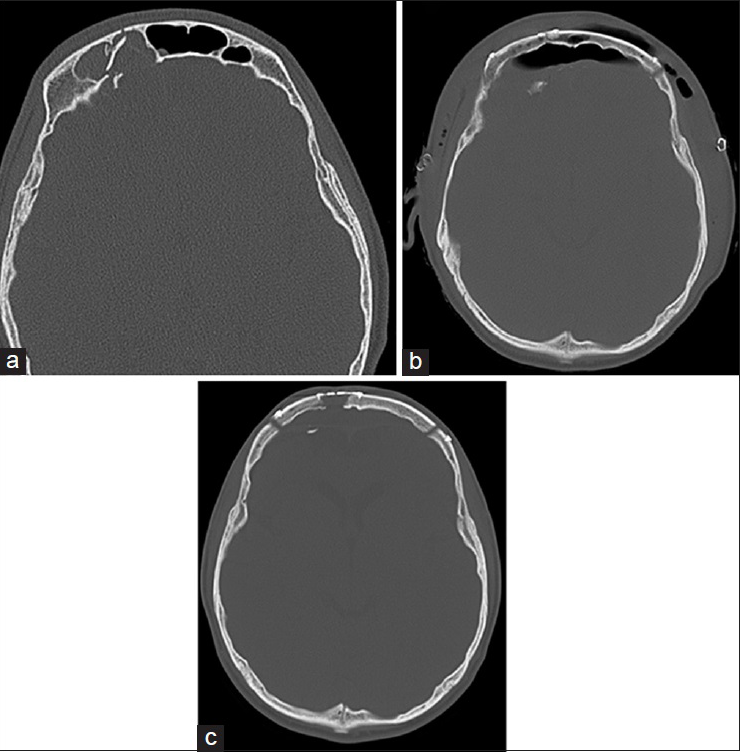

A 25-year-old male suffered a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the face. The bullet had caused massive orbital, facial trauma, including a right frontal sinus fracture with near-complete opacification of the frontal sinus [

Figure 3

Case 2. (a) Axial head computed tomography (CT) scan with bone windows demonstrating right frontal sinus fracture with near-complete opacification of the frontal sinus; the fracture extended through the anterior and posterior tables and was greater than the full width of the frontal sinus. (b) Postoperative head CT showing successful cranialization of the frontal sinuses and residual pneumocephalus. (c) Follow-up head CT, approximately 1.5 months after surgical intervention, demonstrating good bony healing with significant resolution of the cerebral edema and mass effect

DISCUSSION

Frontal sinus injury is common in patients who have experienced trauma. Various treatment algorithms have been proposed, but there is little neurosurgical literature to guide treatment strategies. Mismanagement of frontal sinus fractures may lead to severe infectious and structural complications.[

Blunt force trauma is commonly the primary mechanism of injury, which was also true in our series of patients.[

We found that 67% of the patients in our series had concomitant intracranial injuries, a common finding in patients with frontal sinus fractures with associated NFOT injury.[

Embryology of the frontal sinus and anatomical considerations

Frontal sinus development begins during the fourth or fifth week of gestation and continues through intrauterine growth and the postnatal period and into puberty and even early adulthood.[

The primary pneumatization of the frontal bone occurs slowly, with its completion at the end of the first year of life.[

Anatomic variations in frontal sinus anatomy can complicate clinical decision-making. Although aplasia or hypoplasia may confer a protective effect against CSF leak following frontal bone or facial trauma, other congenital anomalies, such as hyperpneumatization, may predispose to additional complications. Careful review of high-resolution CT scanning can help identify aberrant anatomy and identify potential sources of additional concern; this step may be especially important for preoperative surgical planning.

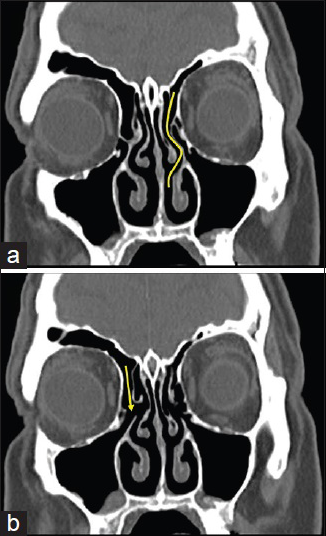

As previously discussed, the presence of NFOT obstruction is paramount in determining appropriate treatment for frontal sinus fractures. The NFOT, the communication between the frontal sinus and the nasal cavity, can be variable; it can exist as an ostium directly communicating with the nasal cavity or as a duct, referred to as the nasofrontal duct. It is important to understand that blunt facial trauma can impair drainage of the frontal sinus distal to the nasal cavity; therefore, understanding the CT and gross anatomy is crucial in correctly triaging these patients. The ostium or duct may be obstructed by direct trauma or secondary swelling to the lateral anterior nasal cavity. If there is swelling, temporary obstruction may lead to a “short-term” outflow obstruction; similarly, if the pathology is more anatomic, “long-term” outflow obstruction may occur. Although thorough clinical evaluation is necessary to determine the presence of CSF leak, use of soft-tissue imaging, either CT or MRI, may be useful in identifying “distal” obstructions that may represent blockage of the NFOT, especially in patients suffering mid-face trauma.

The common embryological and anatomical relationship of the frontal sinus with the ethmoid sinus makes the interplay between these structures quite unique.[

Imaging considerations and NFOT anatomy

CT imaging of the face is routine following blunt trauma, especially when there is obvious face and head involvement. Imaging should be used as an adjunct to clinical examination; however, many trauma patients are sedated, intubated, and unable to comply with provocative maneuvers to identify potential CSF leak. CT may not definitively identify violation of the NFOT because of the complex three-dimensional anatomy in this region; additionally, MRI of the face and orbits is rarely used in the acute setting and may be inferior to CT because of the need to evaluate bony structures and prominences clearly. For patients with no intracranial injury and minimal frontal sinus injury not requiring operative repair, CSF leaks may be investigated with high-resolution CT cisternography or endoscopy utilizing intrathecal fluorescein.[

The frontal sinus egress is via the NFOT. On CT, particularly with multiplanar reconstructions, this can be localized by following the frontal sinus via a pneumatized channel to the anterior ethmoid air cells. The nasofrontal duct can be identified as the duct-like structure that extends from the frontal sinus to the middle meatus, whose walls are formed by the bordering bony anatomic structures. The narrowest portion of the NFOT is the frontal ostium. The superior portion widens into the frontal sinus and the inferior portion expands into the frontal recess or NFOT. The frontal sinus drains through the frontonasal opening, which is usually located in the posteromedial aspect of the floor, and the NFOT course is posterior and caudal [

Longer NFOTs are more susceptible to injury in facial trauma. Obstruction of the NFOT with comminuted fracture fragments can result in scarring and long-term complications including mucocele formation or chronic sinusitis as a result of outflow obstruction.[

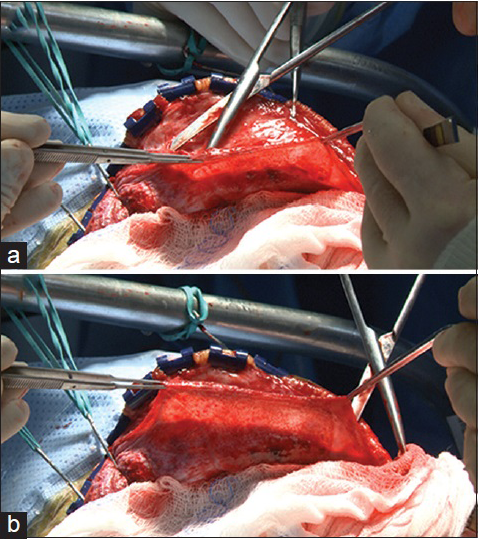

Surgical technique

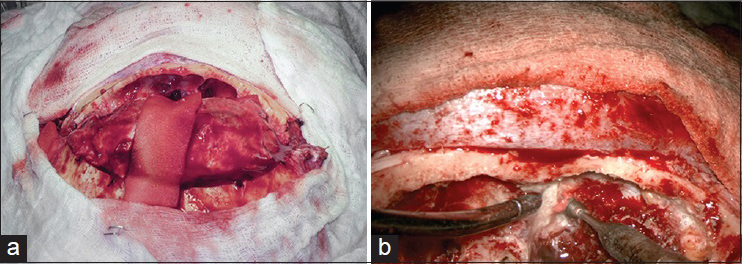

For all patients, we performed a bifrontal craniotomy with complete removal of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus culminating with diamond burr drilling flush to the anterior skull base [

A treatment algorithm focusing on a combination of variables is ideal in the management for patients with frontal sinus injury; however, no straightforward progression exists because of associated intracranial injuries and critical illness in blunt trauma patients, which can lead to delay in the surgical treatment of these patients. Manolidis et al.[

In

All patients in our series underwent cranialization of the frontal sinus. The time to surgical repair depended on many factors including patient stability, patient transfer, and associated injuries. There is no specific recommendation for the timing of frontal sinus repair, however, many factors should be considered. Bellamy et al.[

Bellamy et al.[

There are anecdotal reports on material used to pack the sinus after stripping the mucosa, but there are no long-term studies that show greater efficacy for one particular material. The use of a pericranial flap to layer over the obliterated sinus was well described by Donath et al.,[

The rate of delayed mucocele formation following frontal sinus injury has been previously studied based on anecdotal reports. Until 2004, there were 10 documented cases of delayed mucocele formation as a result of traumatic frontal sinus injury. Koudstaal et al.[

Nonoperative management of frontal sinus fractures

This series focuses on the surgical management of frontal sinus fractures; however, a majority of frontal sinus fractures may be managed conservatively. The absence of CSF leak and NFOT obstruction are two major factors that could predicate conservative management; nonoperative management involves close observation for development of CSF leak and sign and symptoms of meningitis. A majority of patients with frontal sinus injury will not require surgical intervention, and most cases of CSF rhinorrhea acutely after trauma will cease spontaneously.

In this series of patients managed surgically, vaccines were not used in the acute setting. Patients returning for follow-up visits were urged to visit their primary care physicians and update their vaccinations; however, the compliance rate with measure is unknown. Currently, the CDC recommends either the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) or the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) for patients with CSF leaks.[

Patients managed conservatively are treated with standard trauma and neurosurgical protocols for fluid resuscitation and maintenance, with 0.9% sodium chloride solution. Specifically, there is no use of fluid restriction for frontal sinus injury, unless other systemic conditions demand this course of treatment. Most patients with posttraumatic CSF rhinorrhea will have spontaneous resolution. The routine use of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors to decrease CSF production is not typical; however, given its efficacy in patients with suspected high intracranial pressure leaks, it may represent a possible therapeutic option.[

Limitations

This is a case series from a single institution, which may reflect the homogeneity in treatment methods and operative indications. It is a retrospective study, thus subjecting the data to recall bias and limitations based upon availability and accessibility to the medical records. There is a lack of long-term follow-up, which is common in the trauma population.[

CONCLUSIONS

The management of frontal sinus fractures by neurosurgeons can be variable. In our series and review of the literature, the presence of CSF leak, NFOT injury, associated depressed skull fractures and intracranial injuries requiring operative intervention, and potential formation of communicating pathways and infection were all considerations when considering operative repair. Future studies may further define optimal repair technique and materials used obliterate the sinus based on long-term follow-up and outcomes. We have created a treatment algorithm that neurosurgeons can use; however, a multitude of factors play a role in this decision.