- Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital de Especialidades del Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, Mexico City, Mexico

Correspondence Address:

Víctor Correa-Correa, Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital de Especialidades del Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, Mexico City, Mexico.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1063_2024

Copyright: © 2025 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Jesús Eduardo Falcón-Molina, Luis Alfonso Castillejo-Adalid, Isauro Lozano-Guzmán, Joel Abraham Velázquez-Castillo, Víctor Correa-Correa. The far lateral approach for microsurgical management of dumbbell C2 schwannomas. 04-Apr-2025;16:124

How to cite this URL: Jesús Eduardo Falcón-Molina, Luis Alfonso Castillejo-Adalid, Isauro Lozano-Guzmán, Joel Abraham Velázquez-Castillo, Víctor Correa-Correa. The far lateral approach for microsurgical management of dumbbell C2 schwannomas. 04-Apr-2025;16:124. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=13482

Abstract

BackgroundC2 nerve root schwannomas are rare and may be hourglass or dumbbell-shaped at the craniocervical junction. We describe the clinical/radiological features and treatment outcomes of patients with dumbbell C2 schwannomas operated through a far lateral approach and the technical details of this approach.

MethodsBetween 2019 and 2024, seven consecutive patients underwent surgery for dumbbell C2 schwannomas at the Hospital de Especialidades del Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI in Mexico City, Mexico. Data regarding clinical presentation, tumor location, and surgical results were investigated retrospectively in institutional databases.

ResultsThere were 5 males (71.4%) and 2 females (28.5%); the mean age was 50.4 years (range 36–75). The average duration of symptoms before surgery was 16.7 months (range 8–35). Motor deficit (85.7%) and headache (57.1%) were the most frequent symptoms. In all cases, gross total resection (GTR) was successfully achieved. There were no post-surgical complications reported. The mean follow-up time was 21.4 months (range 1–54). Six patients (85.7%) referred completely recovered from their symptoms.

ConclusionDumbbell C2 schwannomas pose a surgical challenge due to the adjacent anatomical structures involved. The far lateral approach enables GTR of these tumors with minimal neurovascular manipulation and excellent functional outcomes.

Keywords: C2 schwannoma, Dumbbell tumor, Far lateral, Spinal schwannoma

INTRODUCTION

Schwannomas represent the second most prevalent tumor among spinal canal neoplasms.[

SS can manifest at any level of the spinal column, with the cervical region being the most frequently affected, followed by the lumbar region.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This study was observational, descriptive, and retrospective. The Local Health Research Committee at our hospital approved it (F-2024-3601-258).

Study population

Between 2019 and 2024, seven consecutive patients underwent surgery for dumbbell C2 schwannomas at the Hospital de Especialidades del Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI in Mexico City, Mexico. The clinical, radiological, and surgical profiles were retrospectively analyzed from institutional databases. All patients underwent a preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to evaluate the extent and configuration of the tumor and a computed tomography (CT) scan to assess the degree of bone involvement in the atlantoaxial joint and to determine the stability of the CVJ to evaluate the need for fixation. In addition, preoperative CT angiography or MRI angiography was conducted to evaluate the course of the vertebral artery (VA). An immediate, simple CT scan was performed on all patients during their immediate post-surgical follow-up. Tumors were classified according to the Eden classification: type I, intradural and extradural; type II, intradural, extradural, and paravertebral; type III, extradural and paravertebral; and type IV, foraminal, and paravertebral.[

Surgical procedure

The patient was positioned in the park bench position and the head was fixed in a Mayfield three-pin head holder. The head was flexed so that only two to three fingers could fit between the patient’s chin and sternum, then rotated ipsilaterally toward the tumor (5–10°) and finally tilted slightly (20–30°) toward the contralateral shoulder. The upper arm was pulled away from the field using adhesive tape. The contralateral arm was secured between the head holder and the end of the operating table, always protecting the axilla with cotton or a foam roll to prevent brachial plexus injury. In this position, the mastoid was the highest point of the field [

Figure 1:

(a) Park bench position for a right far lateral approach. (b) The incision involves the mastoid tip, superior nuchal line, and midline from inion to C4. (c) Image showing mobilization of the nuchal muscles in a single block by subperiosteal dissection. (d) Surgical view showing occipital craniotomy (white arrow), C1 hemilaminectomy, and extradural component of the tumor (white asterisk).

A classic reverse hockey stick incision was made. This incision begins at the mastoid tip, ascends to the superior nuchal line, curves medially to reach the inion, and then proceeds downward to C4 [

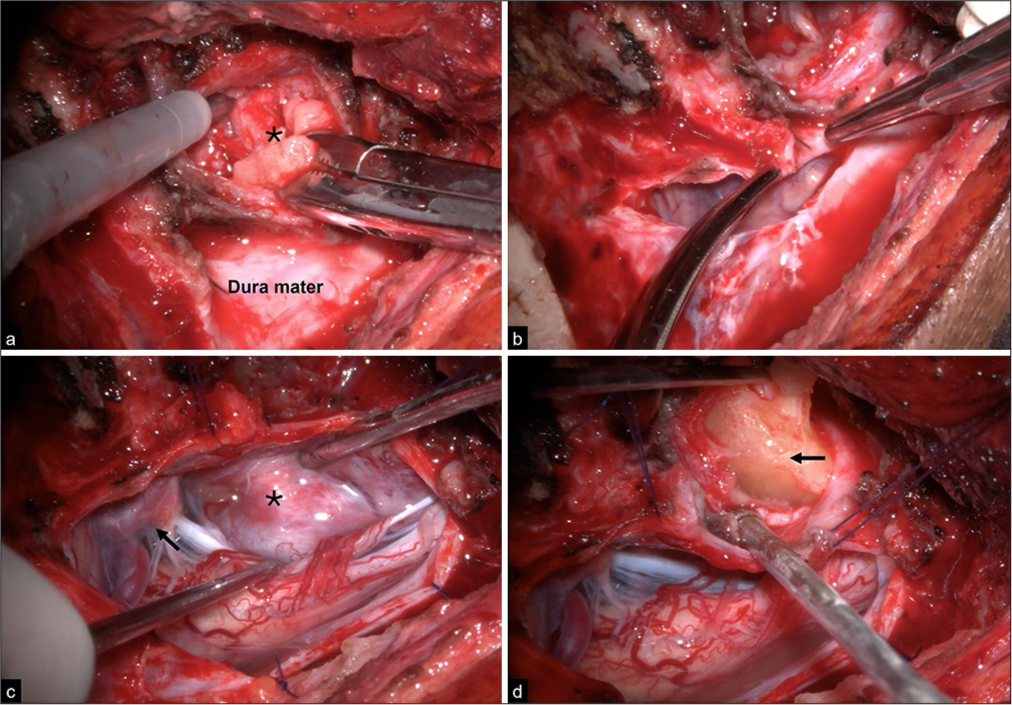

The dura was opened with a laterally based curvilinear incision that passes medially to the entry point of the V3 segment of the VA. Usually, it is unnecessary to mobilize the VA because schwannomas rarely encase it. The dura flap was referred to with several sutures, which are important for enhancing exposure. When the tumor was larger in the intradural space, the intradural component was debulked internally, and its capsule was dissected away from the neurovascular structures, after which the extradural tumor was resected through its capsule. When the extradural component was larger, the tumor was debulked, and the extradural tumor was resected first; once this was completed, the dura was opened, as previously mentioned, to remove the intradural component [

Figure 2:

Intraoperative images of a microsurgical resection of an Eden type II schwannoma through a right far lateral approach. (a and b) The tumor had a significant extradural component (black asterisk) that was first removed, followed by a lateral curvilinear dural opening for intradural resection. (c) The tumor compressed the anterior spinal cord (black asterisk) and contacted the V4 segment (black arrow). (d) Manipulation of the intradural component (black arrow) is feasible with minimal neurovascular retraction.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical features

A total of seven patients with schwannomas arising from C2 nerve roots were included in the study [

Radiological findings

In preoperative MRI, all lesions were dumbbell-shaped. Based on the Eden scale, one tumor was classified as type I, four were type II, and two were type III [

Figure 3:

Preoperative and postoperative images of three cases according to the Eden scale. Eden type I case: (a and b) sagittal and axial T1W gadolinium (Gd-T1W) magnetic resonance images (MRI) showing a large anterolateral and intradural tumor causing significant spinal cord compression (white arrowheads). (c and d) Axial and sagittal T2W images showing gross total resection and myelopathic spinal cord changes (white arrow). Eden type II case: (e and f) coronal and axial Gd-T1W images showing a tumor involving the intra- and extradural space with extension to the contralateral vertebral artery (white arrowheads) and severe compression (red arrowheads). (g and h) Axial and coronal Gd-T1W images showing gross total resection (GTR) and spinal cord space recovery. Eden type III case: (i and j) coronal section showing an enhancing lesion in the extradural space with transforaminal extension shown on the axial T2W section. (k and l) Postoperative MRI sequences showing GTR.

Postoperative clinical outcomes

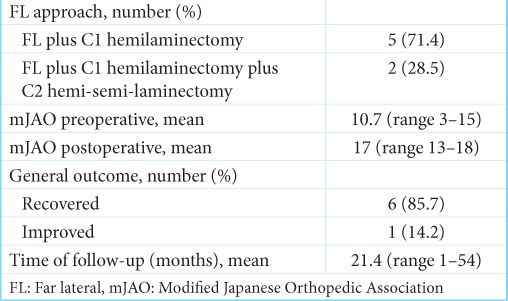

A far lateral approach was used in all patients. C2 hemi-semi laminectomy was performed in only two cases [

DISCUSSION

Schwannomas represent one-third of the primary spinal tumors and can occur at any level along the longitudinal axis.[

Patients with C2 schwannomas initially experience local symptoms such as neck pain or numbness in the suboccipital region.[

On MRI, the tumors are typically predominantly isointense on T1-weighted images, hyperintense on T2-weighted images, and exhibit a homogeneous appearance after gadolinium administration.[

C1–C2 schwannomas are particularly interesting due to their location at the CVJ. The CVJ is a region of complex anatomy that includes the occipital bone and condyles, the atlas, and the axis, along with the lower cranial nerves (CN), C1–C2 nerves, and posterior vertebral circulation. These structures should be taken into account for operative planning concerning schwannomas at the CVJ.[

Management strategies and outcomes

The standard treatment for SS is GTR, with surgical routes varying based on the tumor’s location and origin in the spine.[

While the posterior approach is straightforward and preferred for posteriorly located SS, it may be insufficient for accessing anterior or anterolateral neoplasms; furthermore, this method does not allow access to extraforaminal pathologies. Utilizing a far lateral approach for dumbbell C2 schwannomas presents several benefits, such as reducing spinal cord retraction, enhancing visualization of the anterior brain stem, facilitating access to intra- and extradural tumors, providing early control of the VA, and allowing for an extension of the approach in various ways based on the procedural requirements.[

The far lateral approach usually involves a suboccipital craniectomy or craniotomy, requiring at least the removal of the C1 hemilamina and early identification of VA through dissection of the suboccipital triangle.[

Using this procedure, an overall improvement in symptoms was observed in 85.7% of the cases in this series. There were no significant surgical complications, and no tumor recurrence was detected during the average follow-up period of 21.4 months (range 1–54). The mean mJOA score increased from a preoperative 10.7 (range 3–15) to a postoperative score of 17 (range 13–18).

Surgical pearls

The far lateral approach has been adopted for the resection of tumors located in the upper cervical spinal cord and is suitable for resection of dumbbell C2 schwannomas. This approach demands a thorough understanding of anatomy and careful surgical technique to maximize tumor resection while minimizing complications, particularly to the surrounding neural and vascular structures. Therefore, important considerations must be considered:

(A) Detachment of nuchal muscles: Subperiosteal detachment of the nuchal muscles is performed to skeletonize the suboccipital region, the posterior tip of the occipital condyle, the posterior arch of C1, and, when necessary, the spinous process of C2. (B) Suboccipital craniotomy/craniectomy: While not always required, if performed, a small bone flap is generally sufficient. If occipitocervical fixation is necessary (though usually not needed), the craniotomy/craniectomy should be conducted as laterally as possible to preserve as much of the occipital squama as feasible, thereby ensuring that the instrumentation is not compromised. (C) Resection of C1 and C2: A hemilaminectomy of C1 is performed by crossing slightly over the midline; in some cases, a C2 hemi-semi-laminectomy may be required to enhance exposure. (D) Preservation of joint facets: the joint facets must always be preserved, allowing instability only from the tumor itself. (E) VA preservation: the third segment of the VA must be identified and preserved, necessitating careful dissection and attention to the artery’s anatomy to avoid injury, which could lead to significant neurological deficits. (F) Dural opening: the dura is opened with a laterally based curvilinear incision, which is then reflected with multiple sutures to broaden the surgical field. (G) Tumor resection strategy: if the intradural component is predominant, it should be removed first to identify cranial nerve XI and the fourth segment of the VA. If the extradural component is larger, it should be excised before the dural opening. The VA is frequently displaced superiorly by the tumor. To reduce the risk of vascular injury, the initial resection should commence at the inferior pole of the tumor and proceed in a ventral to dorsal direction.

CONCLUSION

Dumbbell schwannomas of C2 pose a surgical challenge due to their complex location at the CVJ. The far lateral approach is a versatile technique for accessing and resecting tumors with dumbbell characteristics, particularly those situated in a ventrolateral position. In addition, it offers several advantages by minimizing the retraction of adjacent neurovascular structures, providing a broad surgical field to access both intra- and extradural lesions, and facilitating the GTR of these tumors with favorable outcomes.

Ethical approval

The Local Health Research Committee approved the research/study at Hospital de Especialidades del Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, number F-2024-3601-258, dated November 2024.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Ando K, Kobayashi K, Nakashima H, Machino M, Ito S, Kanbara S. Surgical outcomes and factors related to postoperative motor and sensory deficits in resection for 244 cases of spinal schwannoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2020. 81: 6-11

2. Ayoub B. The far lateral approach for intra-dural anteriorly situated tumours at the craniovertebral junction. Turk Neurosurg. 2011. 21: 494-8

3. Carlos-Escalante JA, Paz López AA, Cacho Díaz B, PachecoCuellar G, Reyes-Soto G, Wegman-Ostrosky T. Primary benign tumors of the spinal canal. World Neurosurg. 2022. 164: 178-98

4. Cofano F, Giambra C, Costa P, Zeppa P, Bianconi A, Mammi M. Management of extramedullary intradural spinal tumors: The impact of clinical status, intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring and surgical approach on outcomes in a 12-year double-center experience. Front Neurol. 2020. 11: 598619

5. Conti P, Pansini G, Mouchaty H, Capuano C, Conti R. Spinal neurinomas: Retrospective analysis and long-term outcome of 179 consecutively operated cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2004. 61: 34-43 discussion 44

6. Corrivetti F, Roperto R, Sufianov R, Cacciotti G, Musin A, Sufianov A. Surgical management of spinal schwannomas arising from the first and second cervical roots: Results of a cumulative case series. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine. 2023. 14: 426-32

7. Dobran M, Paracino R, Nasi D, Aiudu D, Capece M, Carrasi E. Laminectomy versus unilateral hemilaminectomy for the removal of intraspinal schwannoma: Experience of a single institution and review of literature. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2021. 82: 552-5

8. Eden K. The dumb-bell tumours of the spine. BJS Br J Surg. 1941. 28: 549-70

9. George B, Lot G. Neurinomas of the first two cervical nerve roots: A series of 42 cases. J Neurosurg. 1995. 82: 917-23

10. Goel A, Kaswa A, Shah A, Rai S, Gore S, Dharurkar P. Extraspinal-interdural surgical approach for C2 neurinomas-report of an experience with 50 cases. World Neurosurg. 2018. 110: 575-82

11. Gottfried ON, Binning MJ, Schmidt MH. Surgical approaches to spinal schwannomas. Contemp Neurosurg. 2005. 27: 1-9

12. Hohenberger C, Hinterleitner J, Schmidt NO, Doenitz C, Zeman F, Schebesch KM. Neurological outcome after resection of spinal schwannoma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020. 198: 106127

13. Krishnan P, Behari S, Banerji D, Mehrotra N, Chabra DK, Jain VK. Surgical approaches to C1C2 nerve sheath tumors. Neurol India. 2004. 52: 319-24

14. Lanzino G, Paolini S, Spetzler RF. Far-lateral approach to the craniocervical junction. Neurosurgery. 2005. 57: 367-71

15. Lenzi J, Anichini G, Landi A, Piciocchi A, Passacantilli E, Pedace F. Spinal nerves schwannomas: Experience on 367 cases-historic overview on how clinical, radiological, and surgical practices have changed over a course of 60 years. Neurol Res Int. 2017. 2017: 3568359

16. Luzzi S, Lucifero AG, Bruno N, Baldoncini M, Campero A, Galzio R. Far lateral approach. Acta Biomed. 2022. 92: e2021352

17. Martin MD, Bruner HJ, Maiman DJ. Anatomic and biomechanical considerations of the craniovertebral junction. Neurosurgery. 2010. 66: 2-6

18. Maurya P, Singh K, Sharma V. C1 and C2 nerve sheath tumors: Analysis of 32 cases. Neurol India. 2009. 57: 31-5

19. McCormick PC. Surgical management of dumbbell tumors of the cervical spine. Neurosurgery. 1996. 38: 294-300

20. Palmisciano P, Ferini G, Watanabe G, Conching A, Ogasawara C, Scalia G. Surgical management of craniovertebral junction schwannomas: A systematic review. Curr Oncol. 2022. 29: 4842-55

21. Parlak A, Oppong MD, Jabbarli R, Gembruch O, Dammann P, Wrede K. Do tumour size, type and localisation affect resection rate in patients with spinal schwannoma?. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022. 58: 357

22. Rhoton AL. The far-lateral approach and its transcondylar, supracondylar, and paracondylar extensions. Neurosurgery. 2000. 47: S195-209

23. Safaee MM, Lyon R, Barbaro NM, Chou D, Mummaneni PV, Weinstein PR. Neurological outcomes and surgical complications in 221 spinal nerves heats tumors. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017. 26: 103-11

24. Safavi-Abbasi S, Senoglu M, Theodore N, Workman RK, Gharabaghi A, Feiz-Erfan I. Microsurgical management of spinal schwannomas: Evaluation of 128 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008. 9: 40-7

25. Seppälä MT, Haltia MJ, Sankila RJ, Jääskeläinen JE, Heiskanen O. Long-term outcome after removal of spinal schwannoma: A clinicopathological study of 187 cases. J Neurosurg. 1995. 83: 621-6

26. Swiatek VM, Stein KP, Cukaz HB, Rashidi A, Skalej M, Mawrin C. Spinal intramedullary schwannomas-report of a case and extensive review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2021. 44: 1833-52

27. Tetreault L, Kopjar B, Nouri A, Arnold P, Barbagallo G, Bartels R. The modified Japanese orthopaedic association scale: Establishing criteria for mild, moderate and severe impairment in patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2017. 26: 78-84

28. Tish S, Habboub G, Lang M, Ostrom QT, Kruchko C, Barnholtz JS. The epidemiology of spinal schwannoma in the United States between 2006 and 2014. J Neurosurg Spine. 2019. 32: 661-6

29. Wang J, Ou W, Wang YJ, Wu AH, Wu PF, Wang YB. Microsurgical management of dumbbell C1 and C2 schwannomas via the far lateral approach. J Clin Neurosci. 2011. 18: 241-6

30. Wang Z, Wang X, Wu H, Chen Z, Yuan Q, Jian F. C2 dumbbell-shaped peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Surgical management and relationship with venous structures. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016. 151: 96-101

31. Wen HT, Rhon AL, Katsuta T, De Oliveira E. Microsurgical anatomy of the transcondylar, supracondylar, and paracondylar extensions of the far-lateral approach. J Neurosurg. 1997. 87: 555-85

32. Xu M, Wang Y, Xu J, Zhong P. Far lateral approach for dumbbell-shaped C1 schwannomas: How I do it. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2024. 166: 78

33. Yu Y, Hu F, Zhang X, Gu Y, Xie T, Junqi G. Application of the hemi-semi-laminectomy approach in the microsurgical treatment of C2 schwannomas. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2014. 27: E199-204

34. Zhu YJ, Ying GY, Chen AQ, Wang LL, Yu DF, Zhu LL. Minimally invasive removal of lumbar intradural extramedullary lesions using the interlaminar approach. Neurosurg Focus. 2015. 39: E10