- Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care, University of California, Los Angeles CA, USA

- Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA

Correspondence Address:

Zafia Anklesaria

Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.177124

Copyright: © 2016 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Anklesaria Z, Al-Helou G. The new era of anticoagulation. Surg Neurol Int 19-Feb-2016;7:22

How to cite this URL: Anklesaria Z, Al-Helou G. The new era of anticoagulation. Surg Neurol Int 19-Feb-2016;7:22. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/new-era-anticoagulation/

For decades, warfarin, a Vitamin K antagonist, was the only oral anticoagulant available to physicians. However, over the last decade, newer agents with different mechanisms of action have become available for the treatment and prevention of thromboembolic events. Physicians must become familiar with the pharmacokinetics, mechanisms of action, indications, risks, and benefits of these agents to become comfortable using them in clinical practice. This review will serve to discuss these aspects of the novel non-Vitamin K oral anticoagulant agents.

Warfarin has been the mainstay of oral anticoagulation. It has been well studied and has proven efficacious in many situations. Its uses include reducing the rate of stroke in atrial fibrillation as well as treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE). It is also used to prevent thrombus formation on mechanical valves. A significant advantage of warfarin is that its effect is reliably reversed by Vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, or prothrombin complex concentrate. However, it has a narrow therapeutic window and a highly unpredictable dose response.[

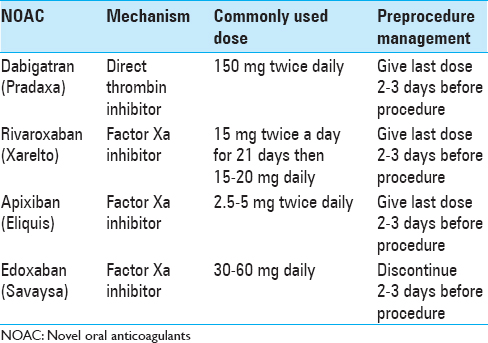

The two main mechanisms of action of the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACS) are direct inhibition of thrombin and inhibition of factor Xa. Thrombin (factor IIa) is the final enzyme in the clotting cascade that cleaves fibrinogen to fibrin. It also activates other procoagulant factors and activates platelets. Inhibition of thrombin interrupts the final steps in the coagulation pathway.[

Dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) is the only oral direct thrombin inhibitor currently approved for use. It is given as a fixed dose (150 mg twice a day) without monitoring. Dosing can be reduced to 110 mg twice a day in patients at high risk for bleeding or with mild renal impairment. The peak effects are noted 2–3 h after ingestion. Renal excretion is the main elimination pathway, and as such, it is contraindicated in patients with creatinine clearance <30 ml/min. In patients with normal renal function, the half-life is approximately 12–17 h.[

Dabigatran does not have a reliable effect on coagulation studies. It will prolong the thrombin time and the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), but it will not reliably prolong the pro-thrombin time. Fortunately, monitoring is not required as drug levels are usually predictable for fixed doses.[

There are three oral direct factors X inhibitors available on the market. Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) is a direct factor X inhibitor that is given at a fixed dose of 10–20 mg twice daily depending on the indication. It is metabolized by the liver and the kidneys and has a half-life of 7–13 h. It reaches its peak efficacy 1–4 h after ingestion. It has been studied for VTE prophylaxis following orthopedic surgeries. Four Phase III studies have compared 10 mg/day of rivaroxaban with 40 mg/day of enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis following hip or knee replacement surgery. In these studies, rivaroxaban was associated with fewer symptomatic VTE events and all-cause mortality. Bleeding events were similar in both groups.[

Just as with dabigatran, routine monitoring of coagulation times is not required for patients on rivaroxaban. The aPTT and anti-Xa activity can be measured and may be prolonged but are not reliable in determining the efficacy of the drug.[

Apixaban (Eliquis) is an oral factor Xa inhibitor with a half-life of 4–9 h. It reaches peak efficacy 1–4 h after ingestion. It is given as a fixed dose without monitoring. The dose varies according to the clinical indication, age, renal function, and weight and it is approved for use in end-stage renal disease. It is indicated for use in treatment and prevention of VTE's and stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. The AMPLIFY study showed that a fixed dose of oral apixaban was as effective as enoxaparin followed by warfarin for the treatment of acute VTE. It was also associated with a clinically significant reduction in bleeding.[

Edoxaban (Savaysa) is another oral direct factor Xa inhibitor. It achieves peak concentration within 1–2 h. Fifty percent of the elimination of edoxaban occurs via the kidneys. It is given as a fixed dose of 30–60 mg once daily. It was found to be noninferior to warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation.[

Despite a large amount of evidence demonstrating the efficacy and safety of the factor Xa inhibitors, the lack of a reversal agent is a significant limitation. To that effect, in a very recent study, a recombinant modified human factor Xa decoy protein called Andexanet alfa (andexanet) has been described. Andexanat binds and sequesters factor Xa inhibitors within the vascular space thus restoring the activity of factor Xa.[

After decades of warfarin being the only anticoagulant available, the NOACS have finally provided physicians and patients with more options. There is a multitude of evidence supporting that they are as efficacious as warfarin. As experience accumulates, it is evident that they are less cumbersome to use and as safe as warfarin. NOACS are slowly but surely becoming the first line for the treatment and prevention of thrombosis in the 21st century.

References

1. Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, Curto M, Gallus AS, Johnson M. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013. 369: 799-808

2. Ahrens I, Lip GY, Peter K. New oral anticoagulant drugs in cardiovascular disease. Thromb Haemost. 2010. 104: 49-60

3. Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G. Pharmacology and management of the Vitamin K antagonists: American College of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8 th Edition). Chest. 2008. 133: 160S-98S

4. Blech S, Ebner T, Ludwig-Schwellinger E, Stangier J, Roth W. The metabolism and disposition of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran, in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008. 36: 386-99

5. Bytzer P, Connolly SJ, Yang S, Ezekowitz M, Formella S, Reilly PA. Analysis of upper gastrointestinal adverse events among patients given dabigatran in the RE-LY trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013. 11: 246-52

6. Chai-Adisaksopha C, Hillis C, Lim W, Boonyawat K, Moffat K, Crowther M. Hemodialysis for the treatment of dabigatran-associated bleeding: A case report and systematic review. J Thromb Haemost. 2015. 13: 1790-8

7. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009. 361: 1139-51

8. Dager WE, Gosselin RC, Kitchen S, Dwyre D. Dabigatran effects on the international normalized ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time, thrombin time, and fibrinogen: A multicenter, in vitro study. Ann Pharmacother. 2012. 46: 1627-36

9. Di Nisio M, Middeldorp S, Büller HR. Direct thrombin inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2005. 353: 1028-40

10. Einstein Investigators, Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD, Brenner B, Buller HR, Decousus H. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010. 363: 2499-510

11. Freyburger G, Macouillard G, Labrouche S, Sztark F. Coagulation parameters in patients receiving dabigatran etexilate or rivaroxaban: Two observational studies in patients undergoing total hip or total knee replacement. Thromb Res. 2011. 127: 457-65

12. Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Halperin JL. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013. 369: 2093-104

13. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011. 365: 981-92

14. Büller HR, Décousus H, Grosso MA, Mercuri M, Middeldorp S. Edoxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013. 369: 1406-15

15. Laux V, Perzborn E, Heitmeier S, von Degenfeld G, Dittrich-Wengenroth E, Buchmüller A. Direct inhibitors of coagulation proteins – The end of the heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin era for anticoagulant therapy?. Thromb Haemost. 2009. 102: 892-9

16. Nutescu E, Chuatrisorn I, Hellenbart E. Drug and dietary interactions of warfarin and novel oral anticoagulants: An update. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011. 31: 326-43

17. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011. 365: 883-91

18. Pollack CV, Reilly PA, Eikelboom J, Glund S, Verhamme P, Bernstein RA. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal. N Engl J Med. 2015. 373: 511-20

19. Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, Mismetti P, Schellong S, Eriksson H. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009. 361: 2342-52

20. Siegal DM, Curnutte JT, Connolly SJ, Lu G, Conley PB, Wiens BL. Andexanet Alfa for the reversal of factor Xa inhibitor activity. N Engl J Med. 2015. 373: 2413-24

21. Southworth MR, Reichman ME, Unger EF. Dabigatran and postmarketing reports of bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013. 368: 1272-4

22. Turpie AG, Lassen MR, Eriksson BI, Gent M, Berkowitz SD, Misselwitz F. Rivaroxaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after hip or knee arthroplasty. Pooled analysis of four studies. Thromb Haemost. 2011. 105: 444-53

23. Wolowacz SE, Roskell NS, Plumb JM, Caprini JA, Eriksson BI. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of venous thromboembolism following total hip or knee arthroplasty. A meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2009. 101: 77-85

24. Wong H, Keeling D. Activated prothrombin complex concentrate for the prevention of dabigatran-associated bleeding. Br J Haematol. 2014. 166: 152-3