- Department of Medical, Um al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia,

- Department of Neurosurgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada,

- Department of Neurosurgery, King Faisal University, Alahsa, Saudi Arabia,

- Department of ENT, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada.

Correspondence Address:

Hassan Khayat, Department of Neurosurgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_574_2023

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Moath Abdullah Khayat1, Hassan Khayat2, Mohamed Rashed Alhantoobi2, Majid Aljoghaiman2,3, Doron D. Sommer4, Almunder Algird2, Daipayan Guha2. Traumatic penetrating head injury by crossbow projectiles: A case report and literature review. 09-Feb-2024;15:35

How to cite this URL: Moath Abdullah Khayat1, Hassan Khayat2, Mohamed Rashed Alhantoobi2, Majid Aljoghaiman2,3, Doron D. Sommer4, Almunder Algird2, Daipayan Guha2. Traumatic penetrating head injury by crossbow projectiles: A case report and literature review. 09-Feb-2024;15:35. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/12740/

Abstract

Background: Low-energy penetrating head injuries caused by arrows are relatively uncommon. The objective of this report is to describe a case presentation and management of self-inflicted intracranial injury using a crossbow and to provide a relevant literature review.

Case Report: A 31-year-old man with a previous psychiatric history sustained a self-inflicted injury using a crossbow that he bought from a department store. The patient arrived neurologically intact at the hospital, fully awake and oriented. He was not able to verbalize due to immobilization of the jaw as well as fixation of his tongue to his hard palate secondary to the position of the arrow. The trajectory of the object showed an entry point at the floor of the oral cavity and an exit through the calvarium just off the midline. The oral and nasal cavity, along with the palate and, the skull base of the anterior cranial fossa, and the left frontal lobe, were all breached. No vascular injury was identified clinically or in imaging. The arrow was surgically removed in the operating room after establishing an elective surgical airway. The floor of the mouth, tongue, and palate was repaired next. A planned delayed cerebrospinal fluid leak repair was performed. The patient made a substantial recovery and was discharged home in good functional status. A systematic literature search was done using Medline for cases with intracranial injuries related to crossbows to review and appraise the available literature.

Conclusion: A thorough assessment in a multidisciplinary trauma center and the availability of a subspecialty care team, including neurosurgery and otolaryngology, are paramount in such cases. The vascular imaging should be done before and after any planned surgical intervention. Emergent and elective surgical airway management should be considered and made available throughout the stabilization and care of the acute injury. Surgical management should be planned to remove the object with adequate exposure to facilitate visualization, removal, and the possible need for further intervention, including anticipating aerodigestive and vascular injuries on removal. Finally, access to weapons and the relation to psychiatric illness should not be overlooked, as many reported cases are self-harming in nature.

Keywords: Crossbow, Neurotrauma, Penetrating head injury, Projectile, Traumatic brain injury

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic intracranial injury caused by penetrating foreign objects is a rare entity, representing 0.4% of all head injuries.[

Historically, a crossbow was a notable weapon used in the Middle Ages for hunting, self-defense, and in times of war. In modern times, its use is mainly related to recreational and hunting activities. This weapon can be defined as a bow that is attached to a trigger device to release the string, with or without a mechanism to tense the bow.[

In this report, we present a systematic review of the literature as well as a case of crossbow-inflicted intracranial injury secondary to a suicide attempt with a special focus on the importance of multidisciplinary teamwork and vascular imaging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was performed in accordance with ethics and regulations adopted by the Declaration of Helsinki, ethics standards, and the University of McMaster and Hamilton Health Sciences, with no formal ethics board approval required.

The study entails a narrative analysis and a detailed description of the clinical presentation, management, and decision-making processes of a self-inflicted head injury using a crossbow. This is supplemented with a comprehensive literature review of previously reported cases. The search was done in Medline using the keywords Crossbow, arrows, head, injury, penetrating, trauma, and brain. We included English literature that provided an adequate description of a crossbow or classical arrow-related injury that extends into the intracranial compartment, regardless of the trajectory. No specification of date of publication, age group, treatment modality, or outcome was used to filter the search results. We excluded cases of arrow-related head injury where intracranial penetration was not confirmed.

Variables and data selection

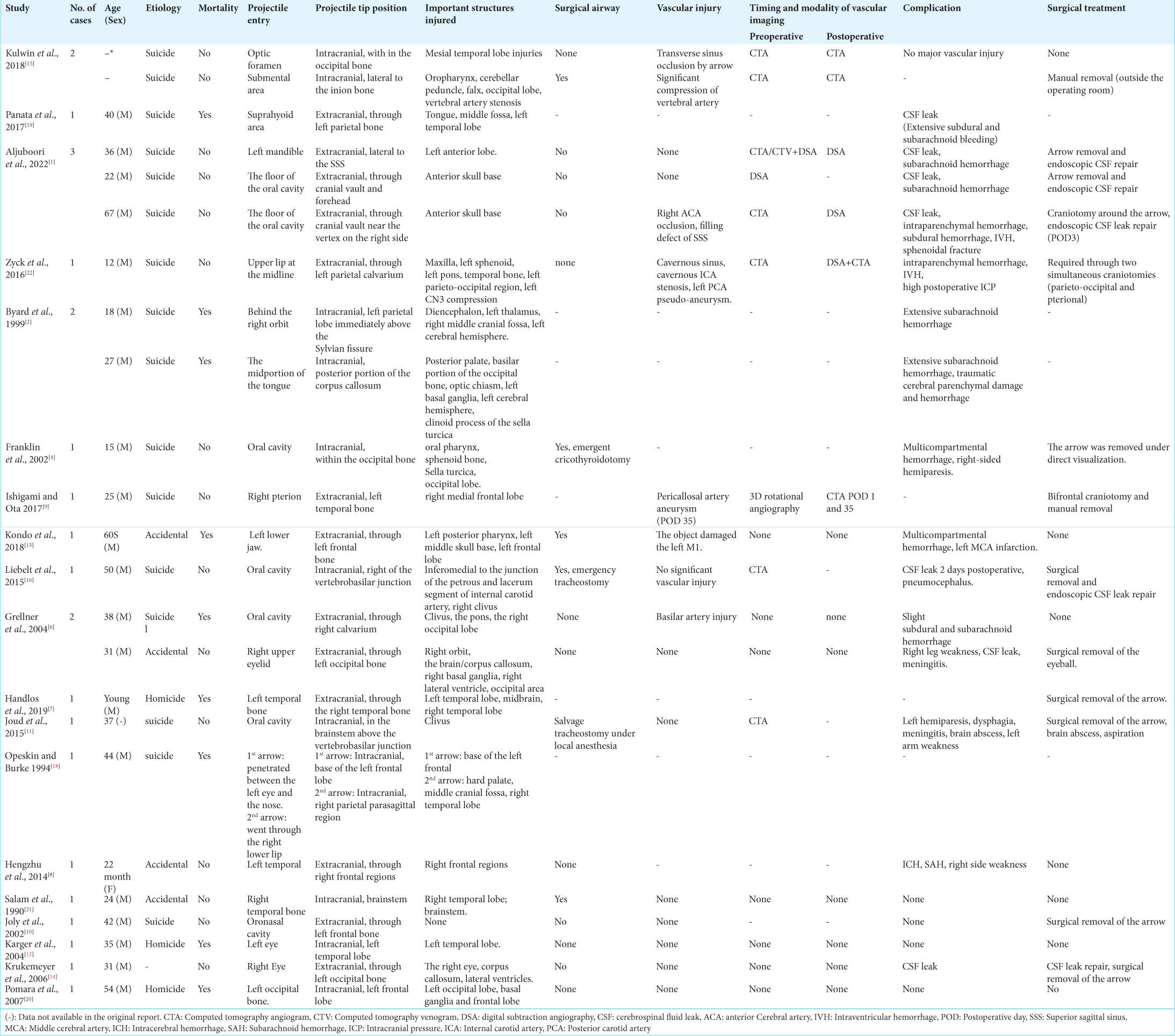

Selected papers were screened for the number of patients, type of weapon, entry point, the final position of the tip, vital structures injured, timing and modality of vascular imaging, clinical outcome, and need and mechanism of surgical removal.

Data management

Three independent reviewers performed the online search separately using the keywords mentioned above and search engines. Screening was performed by evaluating the study title and abstract with full-text review as needed. The conflict was resolved by consensus. Duplicates were eliminated, and the reference lists of selected papers were screened for additional related evidence. Three independent reviewers performed data extraction. Data was then pooled and collected into a data collection table that reflects the collective work of the group.

CASE REPORT

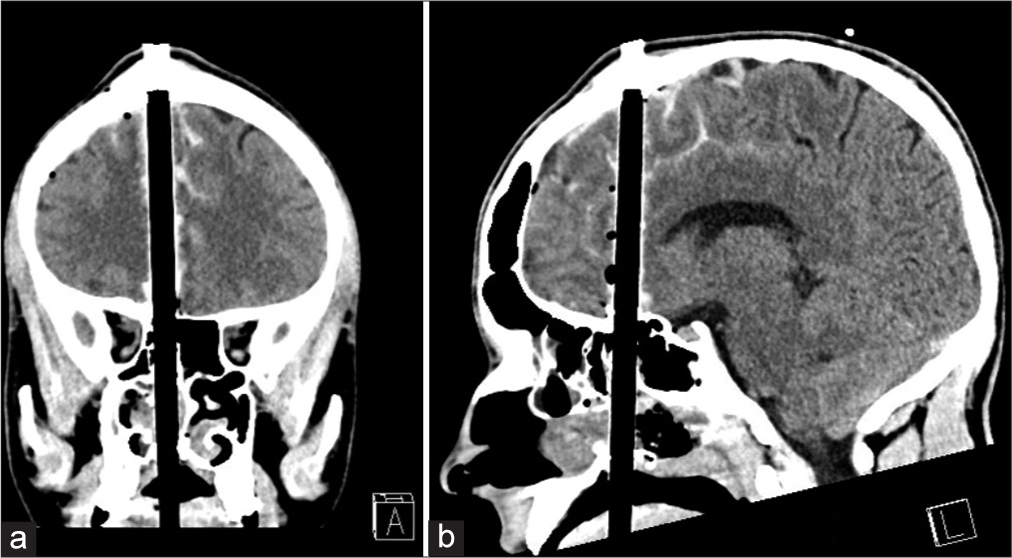

A 31-year-old man with a history of depression and recent discharge from an inpatient psychiatry service purchased a crossbow at a sporting goods store and subsequently attempted suicide by firing the weapon superiorly through the central submental region. The crossbow projectile entered just at the left side of his chin, coursing superiorly through his floor of mouth, tongue, palate, anterior sphenoid sinus, and subsequently intracranially through the frontal lobe, exiting through the calvarium. This resulted in a compound skull fracture with the tip of the arrow projecting out through the scalp. Paramedics brought him in, and the trauma service was notified urgently. The patient had a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15 on arrival; he was awake, alert, and obeying commands in all four extremities with no obvious neurological deficits on assessment. However, he was not able to speak, given the crossbow arrow traversing his tongue and palate structures. A computed tomography (CT) scan/CT angiogram was obtained, which revealed that there were no major intracranial hemorrhages and no intracranial or extracranial vascular injuries from the penetrating object [

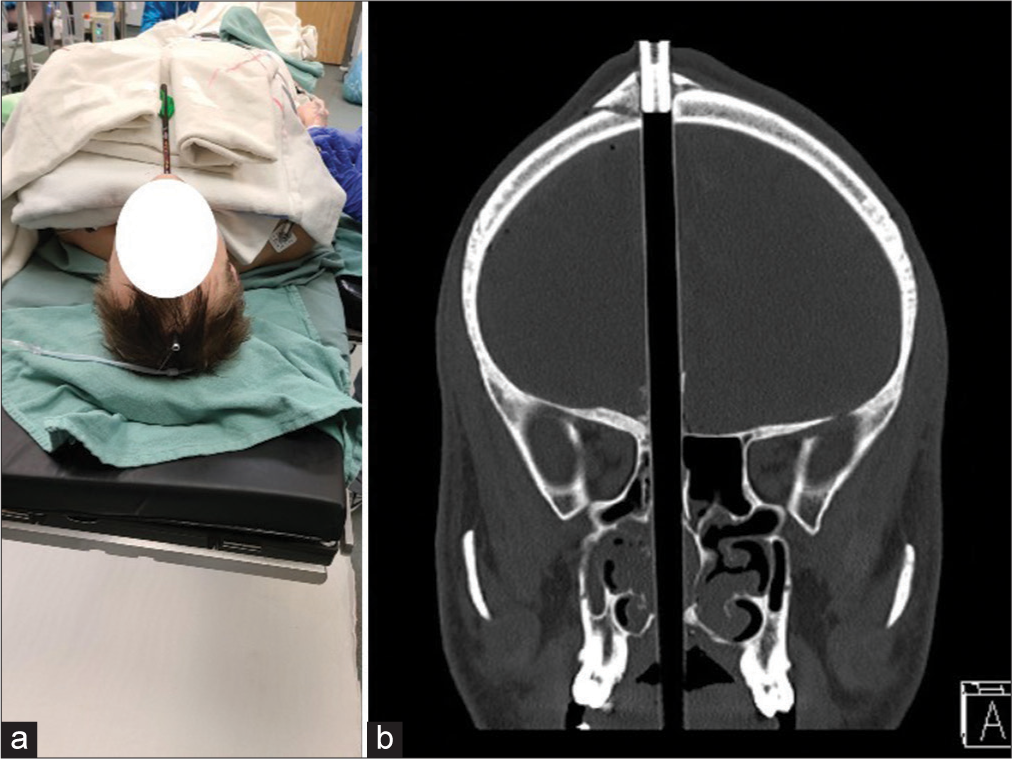

Figure 1:

Penetrating head injury. Suicidal attempt in a 31 Y male. (a) A gross photograph of the patient showing the arrow as it enters through the floor of the oral cavity and exits through the calvarium on the right side. (b) A computed tomography scan (bone window) shows the bony defect in the skull base and the frontal bone fracture at the site of exit.

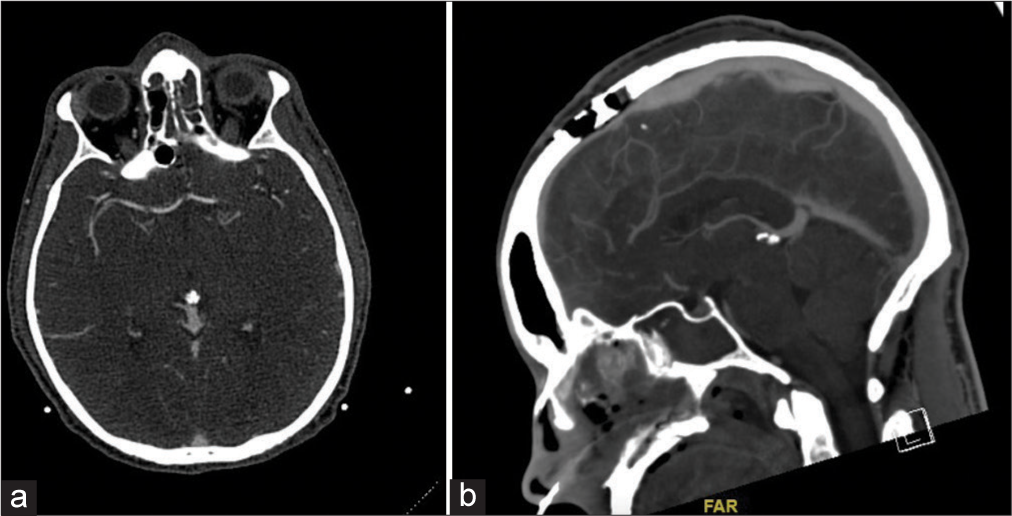

Figure 3:

Vascular imaging. (a) Preoperative computed tomography (CT) angiogram showing no intracranial vascular injury, and (b) a postoperative CT venogram showing normal filling of the superior sagittal sinus underneath the craniotomy site. A computed tomography angiogram done in a postoperative setting (not shown here) was also negative for vascular injury.

A coronal skin incision (involving the crossbow exit site) was made to expose the compound skull fracture. A bifrontal craniotomy was performed to devise a flap between the fractured bone segments and the projectile exit site. The bone was removed in a piecemeal fashion to liberate the arrow from the frontal bone and to have vascular control of the superior sagittal sinus in the event of injury. Once the dura was exposed from sites surrounding the arrow shaft, a careful dural incision was extended to allow for access around the defect. Coagulation around the arrow shaft was avoided to prevent energy transmission to surrounding neural structures. The sharp arrow tip was previously removed before surgery by the emergency medical service team, as it screwed onto the shaft. Following the dural opening, inspection around the shaft of the arrow demonstrated no active hemorrhage and no tissue entanglement. Following this assessment, the arrow was pulled out gently from the entry site (floor of the oral cavity), as the fins on the tail of the arrow were not removable.

Furthermore, this vector avoided the entrainment of oral/nasal contaminants further into the intracranial space. Vital signs were closely monitored as well as evaluation of entry and exit sites to detect any new hemorrhage, change in vitals, or tissue resistance. The object was completely removed with no ensuing adverse events. The dura was reinforced using a synthetic dural replacement material. The bone fragments were examined, debrided, and realigned with plates, bur hole covers, and screws and then placed back to close the defect. There was no cerebrospinal fluid leak (CSF) or rhinorrhea evident at this time; however, the patient was monitored continually for future CSF leaks. Within the same surgery, the otolaryngology team repaired the floor of the mount, tongue, and palate, taking advantage of a distally located surgical airway. Postoperative CT angiogram of the head demonstrated no evidence of vascular injury. The patient spent an uneventful 24 h course in the intensive care unit and was extubated the next morning after ensuring an adequate airway.

Repair of skull-base defect

During the same admission, the patient developed clear, watery rhinorrhea and was taken to the operating room to repair a skull base defect through an endoscopic endonasal approach. The skull base team consisting of otolaryngology/rhinology and neurosurgery located the defect in the roof of the right ethmoid cavity. After performing a right-sided anterior and posterior ethmoidectomy and sphenoidotomy, the team then identified the site of the leak using direct visualization and confirmed with the image guidance system. The edges of the CSF fistula were freshened by removing mucosa from the defect circumferentially and then utilizing an infraumbilical fat graft and ipsilateral nasoseptal flap based on the sphenopalatine artery for closure and sealing of the CSF leak. Intraoperative confirmation of watertight seal with a valsalva maneuver was conducted at the end of the procedure.

Results of the literature review

A total of 24 cases of penetrating head injuries with crossbows have been identified in the literature [

DISCUSSION

Low-energy penetrating head injuries caused by arrows are relatively uncommon in trauma/neurosurgical practice. The paucity of data available in the current literature reflects two important aspects of the topic. First, the data are scarce, and no clear consensus on a treatment protocol has been established. Second, the reports are spaced over a protracted period so that differences in technology, treatment approaches, and decision-making process are evident.

Relation to psychiatric illness

Forensic studies have demonstrated that lethal crossbow injuries are now rarely encountered. A literature review has not shown a clear difference in the pattern of tissue injury between accidental and non-accidental injuries.[

Initial assessment of damage and involvement of a multidisciplinary team

Rapid transfer of the patient to a trauma center with neurosurgical and otolaryngology availability is paramount. The clinical presentation depends on the extent of tissue penetration/injury and the involvement of vital structures along the object’s trajectory. However, due to the low-energy nature of the injury and the limited extent of tissue damage, some patients may retain full consciousness and remain relatively asymptomatic.[

Ballistic studies showed that crossbows can travel at a speed of up to 100 m/s, generating about 135 Joules/s of kinetic energy. This amounts to one-third of the typical energy associated with a 9-mm bullet, which is sufficient to penetrate the skull bone and cause damage to neurovascular structures and surrounding tissues.[

The need for a surgical airway

Self-harm attempts using arrow-type projectiles often involve the upper aerodigestive tract. Our review of the literature revealed that facial and oronasal involvement was seen in 75% of the cases reported with crossbow-related penetrating head injuries. As such, securing the airway in such cases should be prioritized with consideration of potential surgical airway (e.g., awake tracheostomy) if required. Our review of the literature showed that 6/17 patients with orofacial involvement ended up needing a tracheostomy at some point in their care. In our described case, the patient maintained a patent airway until surgery even though oronasal intubation was not possible. Preparedness and close monitoring are needed in these cases to detect early airway complications, such as hemorrhage or edema. A planned awake tracheostomy was undertaken in our case to proceed with general anesthesia without access to the nasal and oral airways.

Vascular imaging: Timing and modality

According to current literature, the rate of vascular injury following penetrating head injury ranges from 5% to 40%.[

Indication for surgical removal and venue of intervention

As opposed to other penetrating head injuries with small fragments retained within the tissues, large crossbows need to be removed as soon as possible.[

Postoperative monitoring and complication

Complications related to penetrating traumatic brain injuries include hematoma, aneurysm, pseudo-aneurysm, carotid-cavernous fistula, meningitis, abscess, seizures, CSF leak, and pneumocephalus.[

CONCLUSION

In crossbow-related head injuries, it is crucial to do a complete examination in a multidisciplinary trauma center. It has access to a specialized care team that includes neurosurgery and otolaryngology. In addition, the ideal timing for vascular imaging is before and after any scheduled surgical operation. Throughout the stabilization and treatment of the acute injury, emergency, as well as elective surgical airway management, should be taken into consideration and made available. The object should be removed surgically with sufficient exposure to allow for visualization, removal, and the potential need for additional intervention, as well as to account for potential vascular and aerodigestive damage that may occur during removal. Furthermore, since many reported cases involve self-harm, it is important to consider controlling access to such tools and to appreciate their relationship to mental illness.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Aljuboori Z, McGrath M, Levitt M, Moe K, Chestnut R, Bonow R. A case series of crossbow injury to the head highlighting the importance of an interdisciplinary management approach. Surg Neurol Int. 2022. 13: 60

2. Byard RW, Koszyca B, James R. Crossbow suicide: Mechanisms of injury and neuropathologic findings. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1999. 20: 347-53

3. Domingo Z, Peter JC, de Villiers JC. Low-velocity penetrating craniocerebral injury in childhood. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994. 21: 45-9

4. Franklin Glen A, Lukan JK. The image of trauma. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 2002. 52: 1009

5. Gokcek C, Erdem Y, Koktekir E, Karatay M, Bayar MA, Edebali N. Intracranial foreign body. Turk Neurosurg. 2007. 2: 121-4

6. Grellner W, Buhmann D, Giese A, Gehrke G, Koops E, Püschel K. Fatal and non-fatal injuries caused by crossbows. Forensic Sci Int. 2004. 142: 17-23

7. Handlos P, Joukal M, Dokoupil M, Uvíra M, Marecová K. Necessary defense or homicide?: The importance of crime scene reconstruction in crossbow injuries. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2019. 40: 293-7

8. Hengzhu Z, Enxi X, Lei S, Xiaodong W, Lun D. A rare case of penetrating brain injury by crossbow in a 22-month-old child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014. 30: 421-3

9. Ishigami D, Ota T. Traumatic pseudo-aneurysm of the distal anterior cerebral artery following penetrating brain injury caused by a crossbow bolt: A case report. NMC Case Rep J. 2017. 5: 21-6

10. Joly LM, Oswald AM, Disdet M, Raggueneau JL. Difficult endotracheal intubation as a result of penetrating cranio-facial injury by an arrow. Anesth Analg. 2002. 1: 231-2

11. Joud A, Merlot I, Klein O. Foreign body of the brainstem by penetrating injury: Conservative treatment. Neurochirurgie. 2015. 61: 401-3

12. Karger B, Bratzke H, Grass H, Lasczkowski G, Lessig R, Monticelli F. Crossbow homicides. Int J Leg Med. 2004. 118: 332-6

13. Kondo T, Takahashi M, Kuse A, Morichika M, Nakagawa K, Tagawa Y. Autopsy case of a penetrating wound to the left cerebral hemisphere caused by an accidental shooting with a crossbow. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2018. 39: 164-8

14. Krukemeyer MG, Grellner W, Gehrke G, Koops E, Püschel K. Survived crossbow injuries. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2006. 27: 274-6

15. Kulwin CG, DeNardo A, Khairi S, Payner T. Neurosurgical management of self-inflicted cranial crossbow injury. World Neurosurg. 2018. 116: 69-71

16. Liebelt BD, Boghani Z, Haider AS, Takashima M. Endoscopic repair technique for traumatic penetrating injuries of the clivus. J Clin Neurosci. 2016. 28: 152-6

17. Offiah C, Twigg S. Imaging assessment of pene-trating craniocerebral and spinal trauma. Clin Radiol. 2009. 64: 1146-57

18. Opeskin K, Burke M. Suicide using multiple crossbow arrows. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1994. 15: 14-7

19. Panata L, Lancia M, Persichini A, Scalise Pantuso S, Bacci M. A crossbow suicide. Forensic Sci Int. 2017. 281: e19-23

20. Pomara C, D’Errico S, Neri M. An unusual case of crossbow homicide. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2007. 3: 124-7

21. Salam AA, Eyres KS, Magides AD, Cleary J. Penetrating brain stem injury from crossbow bolt: A case report and review of the literature. Arch Emerg Med. 1990. 7: 224-7

22. Zyck S, Toshkezi G, Krishnamurthy S, Carter DA, Siddiqui A, Hazama A. Treatment of penetrating non-missile traumatic brain injury. Case series and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2016. 91: 297-307

Oleg Malyshev

Posted February 13, 2024, 10:21 am

Hi, There

We have a similar case-penetrating injury a head by crossbow , which we treated in 2021. Our publication will 1 issue 2024 by “Neurosurgery” Moscow.

Patient has full recovery

Amer Badran

Posted February 15, 2024, 11:57 pm

Thank you so much for your publications!