- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq

- Department of Molecular and Medical Biotechnology, College of Biotechnology, Al-Nahrain University, Baghdad, Iraq

- Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria

- University of Baghdad, Al-Kindy College of Medicine, Baghdad, Iraq

- Department of Neurosurgery, Neurosurgery Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq

- Department of Neurosurgery, College of Medicine, Al-Nahrain University, AlKadhimia, Iraq

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Pennsylvania, United States

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States

Correspondence Address:

Samer S. Hoz, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1104_2024

Copyright: © 2025 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Ahmed Muthana1, Haneen A. Salih2, Mubarak Jolayemi Mustapha3, Hussein Salih Abed4, Alkawthar M. Abdulsada5, Aktham O. Al-Khafaji1, Zainab K. A. Alaraji6, Mayur Sharma7, Samer S. Hoz8. Trigeminal nerve palsy associated with intracranial aneurysms: Scoping review. 07-Feb-2025;16:38

How to cite this URL: Ahmed Muthana1, Haneen A. Salih2, Mubarak Jolayemi Mustapha3, Hussein Salih Abed4, Alkawthar M. Abdulsada5, Aktham O. Al-Khafaji1, Zainab K. A. Alaraji6, Mayur Sharma7, Samer S. Hoz8. Trigeminal nerve palsy associated with intracranial aneurysms: Scoping review. 07-Feb-2025;16:38. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=13373

Abstract

Background: Trigeminal nerve palsy (TNP) in patients with intracranial aneurysms (IAs) results from the disease process or its treatment. We systematically reviewed the literature on trigeminal palsy in patients with IAs.

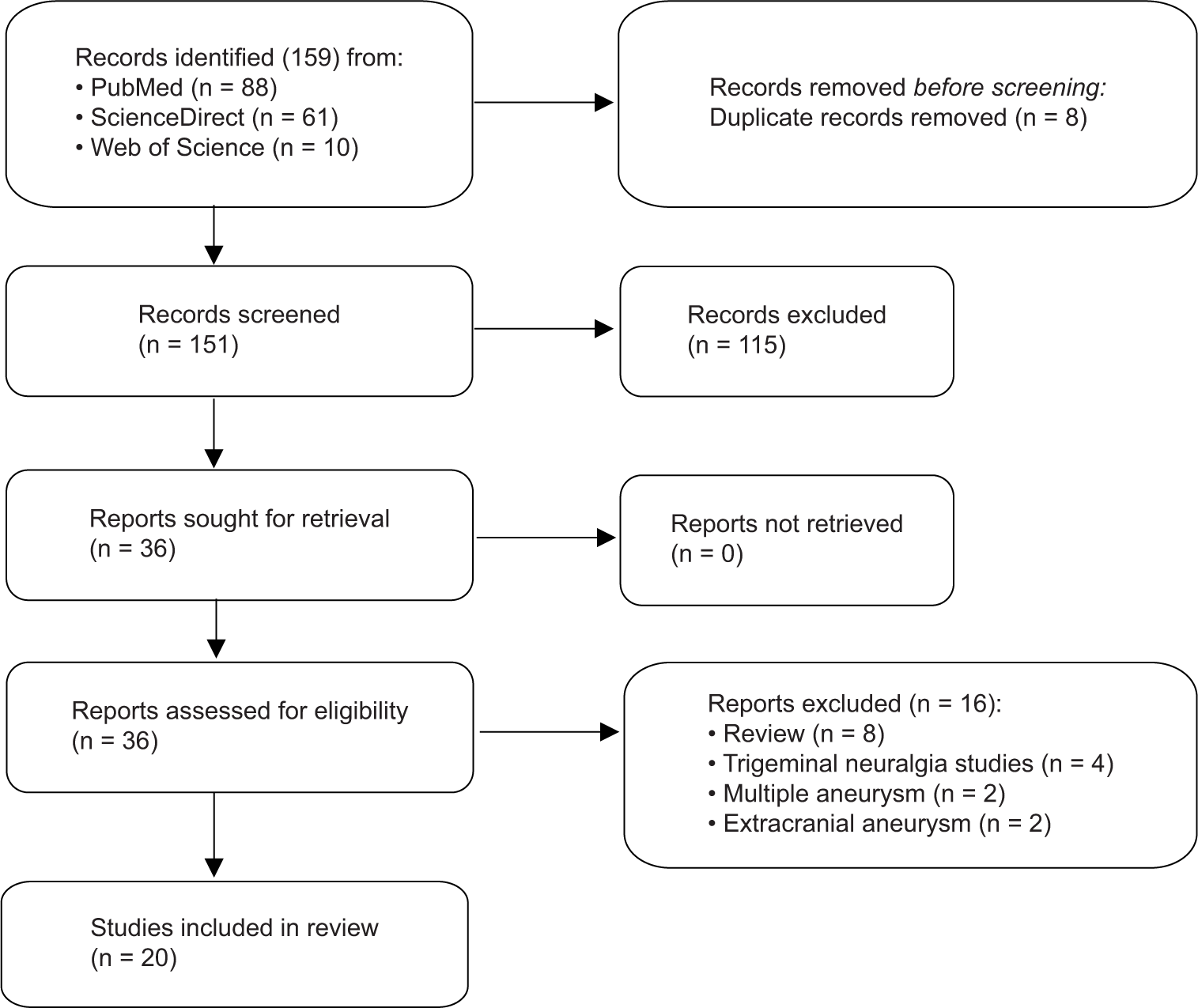

Methods: PubMed, ScienceDirect and Web of Science were searched according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Data extraction and quality assessment were performed according to preestablished guidelines.

Results: Twenty studies were included, yielding 69 patients with TNP and IAs. The mean age was 56.9 years and females accounted for 76%. Among the total cases, a cavernous internal carotid artery aneurysm was found in the vast majority (93%), followed by 7% of aneurysms in the basilar artery-superior cerebellar artery, posterior communicating artery, and anterior communicating artery. 96% of the aneurysms were classified as large to giant-sized. Out of the total number of cases, the majority (90%) exhibited trigeminal palsy at the time of their initial presentation. Only a small proportion (n = 7, 10%) developed fifth nerve palsy subsequent to the treatment of their aneurysms. Concurrent versus isolated TNP were exhibited in 79.7% and 20.3% of the cases, respectively. Finally, in terms of outcome, complete recovery from trigeminal palsy was achieved in 76.7% (26/34), with a duration of resolution of

Conclusion: Trigeminal nerve palsies are correlated with IAs, and this correlation depends mainly on the location and size of the aneurysms.

Keywords: Aneurysm-induced trigeminal nerve palsy, Intracranial aneurysm, Trigeminal nerve palsy, Trigeminal neuropathy

INTRODUCTION

Cranial nerve palsy (CNP) can occur among individuals with cerebral aneurysms as an early clinical presentation or as an outcome of treatments. As a clinical finding, CNP might be part of a symptom cluster in individuals with intracranial aneurysms (IAs).[

Many case series and reports dealing with the role of the fifth cranial nerve in IAs have been found in the literature. Nonetheless, the TNP has not been studied systematically in patients with nurtured IAs. In this systematic review, we comprehensively summarize the research on TNP as a result of IA, emphasizing aneurysmal and TNP features and discussing the potential mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

A systematic review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.[

Study selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were predetermined. Articles were selected if they included at least one patient manifesting TNP and diagnosed with an IA. TNP was defined as a clinical diagnosis denoting the dysfunction of the trigeminal nerve either at presentation or later due to the treatment, as recognized or reported by the respective authors. For IAs, the diagnosis should be based on computed tomography angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, or digital subtraction angiography. Inclusion was also for original data (not duplicated or referenced from other studies). The presence of other CNPs was deemed acceptable; however, traumatic CNPs were excluded. For aneurysms, any extracranial, bilateral, or multiple aneurysms unrelated to the course of the trigeminal nerve were excluded. Exclusions were also for studies with no relevant data on TNP or aneurysmal characteristics, non English language-based studies, conference abstracts, technical reports, book chapters, letters to the editor, editorials, radiological studies, anatomical studies, or those employing animal or cadaveric subjects. Although review articles were excluded from the review, references to these studies were screened to determine whether other original studies were relevant.

Four distinct reviewers systematically scrutinized the titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles, advancing to comprehensive text analysis for those aligning with the stipulated inclusion criteria. Discrepancies, when encountered, were mediated by a fifth reviewer (A.M.). Following the pre-established guidelines, relevant articles were integrated, and their reference lists were examined for additional pertinent studies.

Data extraction

Five distinct reviewers initiated the data extraction, which was subsequently cross-checked for accuracy by reviewer A.M. Missing data from the included studies were not reported by the authors. The data assessment parameters encompassed author - year, country of origin, study design, population size, age demographics, gender distribution, the status of aneurysm rupture with Hunt and Hess score and modified Fisher scale, aneurysm characteristics which include location, size, side and morphological type, trigeminal palsy characteristics which include timing of palsy, laterality, side, multiplicity, severity, description of trigeminal branches involvement, treatment method, outcome of trigeminal palsy, duration of resolution in months, follow-up duration in months, and modified Rankin scale. Other parameters, such as presentation description, potential mechanism of palsy, and the presence of daughter cysts, were also included.

Data synthesis, quality assessment, and statistical analyses

The primary outcome was centered on delineating the clinical characteristics of patients with TNP and IAs alongside their associated outcomes. Jamovi 2.4.1.0 was used for the descriptive analysis. Continuous variables are summarized as medians and ranges, while categorical variables are as frequencies and percentages. For each article, the level of evidence was independently evaluated by two reviewers (A.M. and H.A.) upon the 2011 Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine guidelines, and the risk of bias was assessed using the JBI checklists.[

RESULTS

Study selection

General aneurysmal characteristics

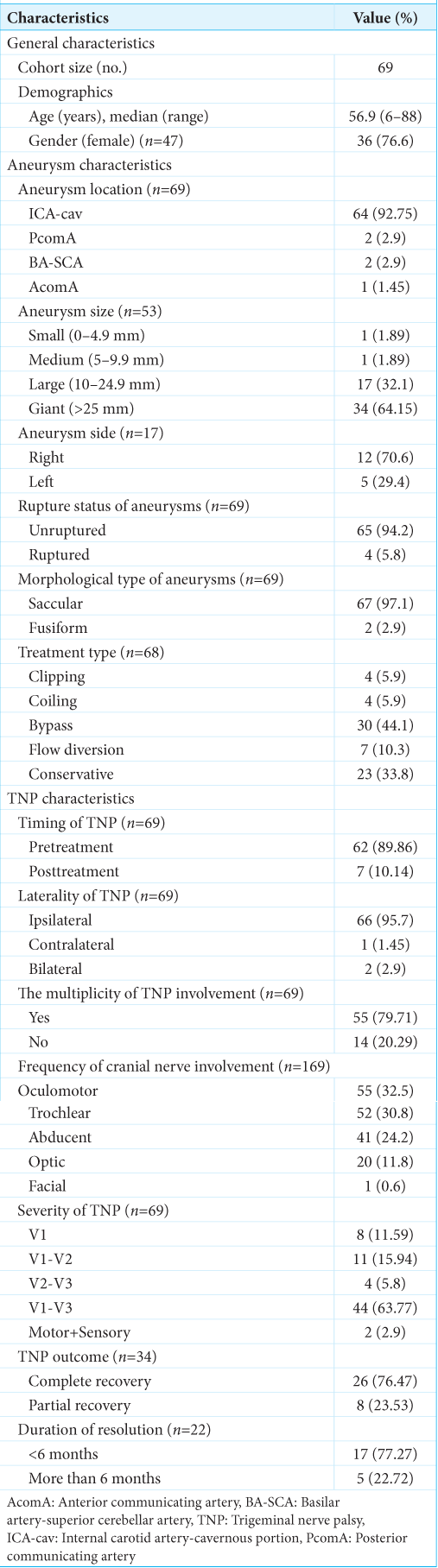

A cohort of 69 patients was included in our study [

TNP characteristics

Within the scope of our study, we aimed to ascertain the temporal correlation between TNP and aneurysmal treatment. The majority of cases had TNP at the presentation (n = 62, 89.9%). Only 7 cases (10.1%) had TNP after the treatment of aneurysm. In the study, TNP laterality was examined among the included cases. Studies that did not specify the side of TNP cases were considered ipsilateral. Consequently, 66 (95.7%) exhibited ipsilateral TNP, 2 (2.9%) bilateral TNP, and a single case (1.45%) contralateral TNP. For the multiplicity of TNP involvement, 55 (79.7%) had CNP other than trigeminal palsy, and the remaining 14 (20.3%) had isolated TNP. Further analysis of the former group revealed that oculomotor CNP was the nerve dysfunction most commonly associated with TNP, followed by trochlear and abducent (combined 87.5%). Concerning the severity of TNP, the majority of cases exhibited sensory involvement in the branches V1-V3 (n = 44, 63.8%), with V1-V2 branches following suit (n = 11, 15.9%) [

DISCUSSION

Anatomical association of TNP and IA

The trigeminal nerve is the largest and most complex of the cranial nerves. It serves as a major conduit of sensory input from the face and provides motor innervation to the muscles of mastication. Its course from origin to insertion is divided into the brainstem, cisternal segment, Meckel’s cave segment, trigeminal ganglion, and peripheral divisions (ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular divisions).[

Our objective in this systematic review was to encompass all instances of trigeminal palsy attributed to IAs, whether they occurred before or following treatment, and discuss the potential mechanisms that lie behind it.

Intracranial aneurysmal characteristics

The location of the IAs in patients with TNP was examined to determine its significance. In our review, cavernous ICA aneurysm was found in the vast majority of TNP cases (93%), followed by BA-SCA and PcomA (about 6%). It seems evident that the anatomical proximity of these aneurysms to the course of the trigeminal nerve plays a major role in the causation of the TNP, as the mass effect exerted by them is a relatively common etiology for CNP at presentation time.[

The underlying mechanism of CNP in unruptured aneurysms is distinct from that observed in ruptured aneurysms. Various prospective explanations for the pathogenesis of this correlation have been put forth in the literature. As described previously, in the case of an unruptured IA, the cranial nerve may experience direct pressure from the expanding aneurysmal sac or nerve ischemia.[

A norm, nevertheless, is subjected to exceptions. Thorat and Hwang discovered a noteworthy case involving TNP and a ruptured small AcomA aneurysm.[

Trigeminal palsy characteristics

Studying the features of TNP revealed that most of these cases exhibited ipsilateral TNP and had complete sensory involvement in the branches V1-V3. Partial involvement of the trigeminal nerve branches was found in scattered cases, and only two cases exhibited dysfunction of the motor component of the trigeminal nerve. In addition, the involvement of other cranial nerves was also dominant, notably the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducent nerves. The presence of these nerves in a confined space renders them vulnerable to mass compression by adjacent arterial aneurysms, especially cavernous ICA aneurysms, which were seen in the majority of the included cases. In our analysis, the concurrent TNP was seen in about 80% of the studied cases. Most of these subjects had large to giant-sized cavernous ICA aneurysms. Multiple combinations of cranial nerve palsies attributed to cavernous ICA aneurysms have been reported in the literature.[

Notwithstanding the restricted number of studied cases, the analysis of long-term recovery from TNP unveiled a commendable recovery rate, estimated at approximately 100% of partial to complete recovery, within a timeframe of <6 months. This holds significant clinical relevance during the initial consultation with the patient, as it aids in elucidating the prognosis and potential for long-term recovery of their trigeminal palsy.

In brief, the initial analysis of the correlation between TNP and IA revealed that the most frequently documented causative aneurysms of TNP in the literature are unruptured, large to giant-sized cavernous ICA aneurysms, mostly in the pretreatment state, ipsilateral, and concurrent with other CNPs. Finally, most cases exhibited a favorable outcome, with a majority achieving complete resolution of their TNPs.

Limitations

Our study has certain limitations. Diagnosing TNP is challenging, relying heavily on clinical confirmation. Most reviewed articles were retrospective, introducing inherent selection bias due to preexisting data. Although we found no evidence of publication bias, institutional reporting bias cannot be entirely ruled out. Our focus on English-language articles may have excluded relevant research in other languages, possibly introducing language bias. In addition, the majority of included studies were cohort analyses and case reports, which inherently emphasize unique clinical scenarios, potentially deviating from broader patient population characteristics.

Despite these limitations, our review offers valuable insights into the TNP-IA relationship, providing a comprehensive overview of the literature and highlighting areas for future research.

CONCLUSION

Trigeminal nerve palsies are correlated with IAs, and this correlation depends on the location and size of the aneurysms, typically leading to ipsilateral complete facial numbness at the presentation, usually with the involvement of other cranial nerves.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent is not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Supplementary data available on:

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Date I, Ohmoto T. Long-term outcome of surgical treatment of intracavernous giant aneurysms. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1998. 38: 62-9

2. Durner G, Piano M, Lenga P, Mielke D, Hohaus C, Guhl S. Cranial nerve deficits in giant cavernous carotid aneurysms and their relation to aneurysm morphology and location. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2018. 160: 1653-60

3. Eddleman CS, Hurley MC, Bendok BR, Batjer HH. Cavernous carotid aneurysms: To treat or not to treat?. Neurosurg Focus. 2009. 26: E4

4. Hahn CD, Nicolle DA, Lownie SP, Drake CG. Giant cavernous carotid aneurysms: clinical presentation in fifty-seven cases. J Neuroophthalmol. 2000. 20: 253-8

5. Howick J. The Oxford 2011 levels of evidence. Available From: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653.

6. Joo W, Yoshioka F, Funaki T, Mizokami K, Rhoton AL. Microsurgical anatomy of the trigeminal nerve. Clin Anat. 2014. 27: 61-88

7. Kashihara K, Ito H, Yamamoto S, Yamano K. Raeder’s syndrome associated with intracranial internal carotid artery aneurysm. Neurosurgery. 1987. 20: 49-51

8. Kassis SZ, Jouanneau E, Tahon FB, Salkine F, Perrin G, Turjman F. Recovery of third nerve palsy after endovascular treatment of posterior communicating artery aneurysms. World Neurosurg. 2010. 73: 11-6

9. Kikkawa Y, Kayahara T, Teranishi A, Shibata A, Suzuki K, Kamide T. Predictors of the resolution of cavernous sinus syndrome caused by large/giant cavernous carotid aneurysms after parent artery occlusion with high-flow bypass. World Neurosurg. 2019. 132: e637-44

10. Kobets AJ, Scoco A, Nakhla J, Brook AL, Kinon MD, Baxi N. Flow-diverting stents for the obliteration of symptomatic, infectious cavernous carotid artery aneurysms. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2018. 14: 681-5

11. Kono K, Okada H, Terada T. A novel neck-sealing balloon technique for distal access through a giant aneurysm. Oper Neurosurg. 2013. 73: onsE302-6

12. Linskey ME, Sekhar LN, Hirsch W, Yonas H, Horton JA. Aneurysms of the intracavernous carotid artery: Clinical presentation, radiographic features, and pathogenesis. Neurosurgery. 1990. 26: 71-9

13. Matsumoto K, Kato A, Fujii K, Fujinaka T, Fukuhara R. Bilateral giant intracavernous carotid artery aneurysms mimicking a cavernous sinus neoplasm--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1996. 36: 583-5

14. Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, editors. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk, in Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. Adelaide, Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. p. 217-69

15. Moon K, Albuquerque FC, Ducruet AF, Crowley RW, McDougall CG. Resolution of cranial neuropathies following treatment of intracranial aneurysms with the Pipeline Embolization Device. J Neurosurg. 2014. 121: 1085-92

16. Nam KH, Choi CH, Lee JI, Ko JG, Lee TH, Lee SW. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms with oculomotor nerve palsy: Clinical outcome between surgical clipping and coil embolization. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2010. 48: 109-14

17. Nathal E, Degollado-García J, Bonilla-Suastegui A, RodríguezRubio HA, Ferrufino-Mejia BR, Casas-Martínez MR. Microsurgical treatment of a giant intracavernous carotid artery aneurysm in a pediatric patient: Case report and literature review. Cureus. 2023. 15: e34010

18. Nishimoto K, Ozaki T, Kidani T, Nakajima S, Kanemura Y, Yamazaki H. Flow diverter stenting for symptomatic intracranial internal carotid artery aneurysms: Clinical outcomes and factors for symptom improvement. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2023. 63: 343-9

19. Nishino K, Ito Y, Hasegawa H, Shimbo J, Kikuchi B, Fujii Y. Development of cranial nerve palsy shortly after endosaccular embolization for asymptomatic cerebral aneurysm: Report of two cases and literature review. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2009. 151: 379-83

20. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021. 372: n71

21. Patel K, Guilfoyle MR, Bulters DO, Kirollos RW, Antoun NM, Higgins JN. Recovery of oculomotor nerve palsy secondary to posterior communicating artery aneurysms. Br J Neurosurg. 2014. 28: 483-7

22. Perrini P, Bortolotti C, Wang H, Fraser K, Lanzino G. Thrombosed giant intracavernous aneurysm with subsequent spontaneous ipsilateral carotid artery occlusion. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005. 147: 215-6

23. Ros de San Pedro. Posterior communicating artery aneurysms causing facial pain: A comprehensive review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017. 160: 59-68

24. Ros de San Pedro. Superior cerebellar artery aneurysms causing facial pain: A comprehensive review. Oper Neurosurg. 2020. 18: 2-11

25. Sano H, Jain VK, Kato Y, Kamei Y, Asai T, Katada K. Bilateral giant intracavernous aneurysms. Technique of unilateral operation. Surg Neurol. 1988. 29: 35-8

26. Smith JH, Cutrer FM. Numbness matters: A clinical review of trigeminal neuropathy. Cephalalgia. 2011. 31: 1131-44

27. Stiebel-Kalish H, Kalish Y, Bar-On RH, Setton A, Niimi Y, Berenstein A. Presentation, natural history, and management of carotid cavernous aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2005. 57: 850-7

28. Sudhoff H, Stark T, Knorz S, Luckhaupt H, Borkowski G. Massive epistaxis after rupture of intracavernous carotid artery aneurysm. Case report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000. 109: 776-8

29. Suzuki N, Suzuki M, Araki S, Sato H. A case of multiple cranial nerve palsy due to sphenoid sinusitis complicated by cerebral aneurysm. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2005. 32: 415-9

30. Tan H, Huang G, Zhang T, Liu J, Li Z, Wang Z. A retrospective comparison of the influence of surgical clipping and endovascular embolization on recovery of oculomotor nerve palsy in patients with posterior communicating artery aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2015. 76: 687-94

31. Tatsui CE, Prevedello DM, Koerbel A, Cordeiro JG, Ditzel LF, Araujo JC. Raeder’s syndrome after embolization of a giant intracavernous carotid artery aneurysm: Pathophysiological considerations. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2005. 63: 676-80

32. Terao S, Hara K, Yoshida K, Ohira T, Kawase T. A giant internal carotid-posterior communicating artery aneurysm presenting with atypical trigeminal neuralgia and facial nerve palsy in a patient with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: A case report. Surg Neurol. 2001. 56: 127-31

33. Thorat JD, Hwang PY. Peculiar geometric alopecia and trigeminal nerve dysfunction in a patient after Guglielmi detachable coil embolization of a ruptured aneurysm. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007. 16: 40-2

34. Uchikawa H, Nishi T, Kaku Y, Goto T, Kuratsu JI, Yano S. Delayed development of aneurysms following gamma knife surgery for trigeminal neuralgia: Report of 2 cases. World Neurosurg. 2017. 99: 813.e13-9

35. Vanikieti K, Poonyathalang A, Jindahra P, Cheecharoen P, Chokthaweesak W. Occipital lobe infarction: A rare presentation of bilateral giant cavernous carotid aneurysms: A case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018. 18: 25

36. Xu DS, Hurley MC, Batjer HH, Bendok BR. Delayed cranial nerve palsy after coiling of carotid cavernous sinus aneurysms: Case report. Neurosurgery. 2010. 66: E1215-6

37. Zager EL. Isolated trigeminal sensory loss secondary to a distal anterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysm: Case report. Neurosurgery. 1991. 28: 288-91

38. Zelman S, Goebel MC, Manthey DE, Hawkins S. Large posterior communicating artery aneurysm: Initial presentation with reproducible facial pain without cranial nerve deficit. West J Emerg Med. 2016. 17: 808-10

39. Zheng F, Chen X, Zhou J, Pan Z, Xiong Y, Huang X. Clipping versus coiling in the treatment of oculomotor nerve palsy induced by unruptured posterior communicating artery aneurysms: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2021. 206: 106689

40. Zis P, Fragkis S, Lykouri M, Bageris I, Kolovos G, Angelidakis P. From basilar artery dolichoectasia to basilar artery aneurysm: natural history in images. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015. 24: e117-9