- Professor of Clinical Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, State University of N.Y. at Stony Brook, New York, USA

- Chief of Neurosurgical Spine and Education, NYU Winthrop Hospital, NYU Winthrop Neuro Science, Mineola, New York, USA

Correspondence Address:

Nancy E. Epstein

Professor of Clinical Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, State University of N.Y. at Stony Brook, New York, USA

Chief of Neurosurgical Spine and Education, NYU Winthrop Hospital, NYU Winthrop Neuro Science, Mineola, New York, USA

DOI:10.4103/sni.sni_196_18

Copyright: © 2018 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Nancy E. Epstein. When and if to stop low-dose aspirin before spine surgery?. 03-Aug-2018;9:154

How to cite this URL: Nancy E. Epstein. When and if to stop low-dose aspirin before spine surgery?. 03-Aug-2018;9:154. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/when-and-if-to-stop-low%e2%80%91dose-aspirin-before-spine-surgery/

Abstract

Background:Prior to spine surgery (SS), we ask whether and when to stop low-dose aspirin (LD-ASA), particularly in patients with significant cardiovascular disease (CAD). Although platelets typically regenerate in 10 days, it can take longer in older patients.

Methods:Here we reviewed several studies regarding the perioperative risks/complications [e.g. hemorrhagic complications, estimated blood loss (EBL), continued postoperative drainage] for continuing vs. stopping LD-ASA at various intervals prior to lumbar SS.

Results:Multiple studies confirmed the increased perioperative risks for continuing LD-ASA throughout SS, or when stopping it for just 3–7 preoperative days; however, there were no increased risks if stopped between 7 to 10 days postoperatively. Other studies documented no increased perioperative risk for continuing LD-ASA throughout SS, although some indicated increased morbidity (e.g., one patient developed a postoperative hematoma resulting in irreversible paralysis).

Conclusions:Several studies demonstrated more hemorrhagic complications if LD-ASA was continued throughout or stopped just 3 to up to 7 days prior to SS. However, there were no adverse bleeding events if stopped from 7–10 days preoperatively. As a spine surgeon who wishes to avoid a postoperative epidural hematoma/paralysis, I would recommend stopping LD-ASA 10 days or longer prior to SS. Nevertheless, each spine surgeon must determine what is in the “best interest” of their individual patient. Certainly, we need future randomized controlled trials to better answer: when and if to stop LD-ASA before spine surgery.

Keywords: Bleeding complications, cardiac risk, hemorrhagic sequelae, low-dose aspirin, perioperative spine surgery, postoperative drainage, prophylaxis

INTRODUCTION

For patients on low-dose aspirin (LD-ASA) (e.g., 81–100 mg) prophylaxis for cardiovascular disease (CAD) (e.g., stents, bypasses, other), spine surgeons frequently confront whether or when to stop therapy prior to spine surgery (SS). Platelets typically regenerate in 10 days, although it may take longer for older patients. In this editorial and focused review of the literature, we briefly compared the perioperative risks/complications [e.g., hemorrhagic complications, estimated blood loss (EBL), continued postoperative drainage] for continuing vs. discontinuing (e.g. stopping LD-ASA from 3-<7 and from 7-10 days) LD-ASA at different intervals prior to lumbar SS.

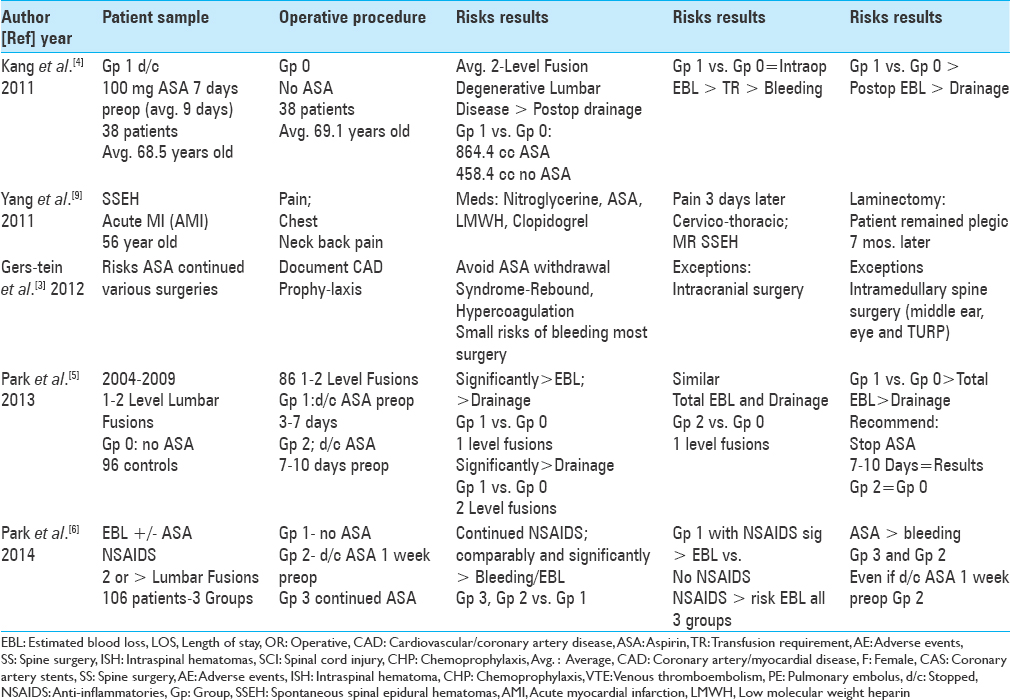

Part 1: Increased perioperative bleeding risks using low-dose aspirin (LD-ASA) for spine surgery [ Table 1 ]

Increased perioperative bleeding risks when low-dose aspirin was continued or not stopped long enough prior to lumbar spine surgery

Several series documented the increased perioperative risks/complications (e.g., hemorrhagic complications, EBL, continued postoperative drainage) when LD-ASA was continued and/or stopped for just 3 up to 7 days preoperatively vs. finding no such risks for LD-ASA stopped for 7–10 (average 9) preoperative days.[

Increased blood loss with low-dose aspirin and/or anti-inflammatories (NSAIDS) for patients undergoing spinal surgery

Increased hemorrhagic risks were observed in Park et al. (2014) where patients were divided into three groups based on LD-ASA use, and additionally given NSAIDS prior to 2 or more level lumbar fusions [

Surgical risk for bleeding on low-dose aspirin increased in cranial/selective spinal surgery

Gerstein et al. (2012) determined that continuing LD-ASA to avoid perioperative rebound/hypercoagulation syndrome resulted in only a small increased risk of bleeding for most operations, notably excluding cranial surgery, intramedullary spine surgery, middle ear surgery, eye surgery, and transurethral prostatectomy [

Case: Acute spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma due to antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy for acute myocardial infarction

In Yang et al. (2010), a 56-year-old male presented with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) for which he was placed on nitroglycerine, aspirin, low-molecular-weight heparin prophylaxis, and Clopidogrel [

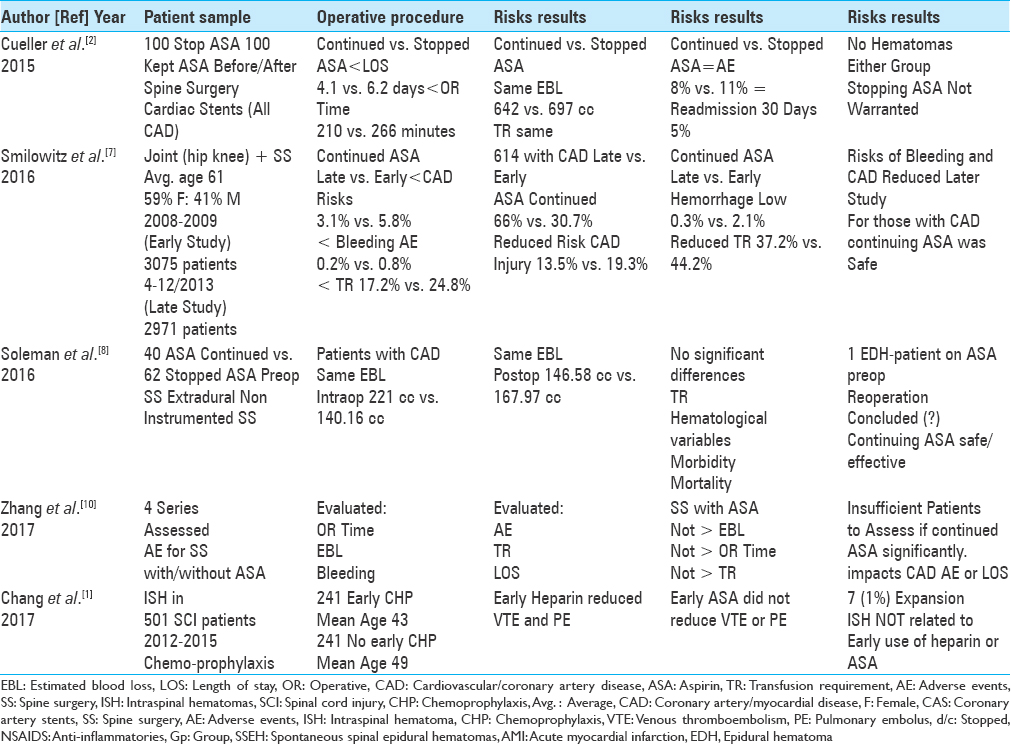

Part II: No increased risks for continuing low-dose aspirin (LD-ASA) for spine surgery [ Table 2 ]

Studies support continuation of low-dose aspirin for spine surgery but with instances of acute epidural hematoma/permanent paraplegia

Although several studies supported continuing LD-ASA throughout spine surgery, some series cited significant perioperative morbidity (e.g., permanent paraplegia).[

Postoperative epidural hematoma in patient continuing perioperative ASA

Soleman et al. (2016) compared two patient groups undergoing extradural noninstrumented spinal surgery; in 40 patients, LD-ASA was continued, whereas in 62 patients, LD-ASA was stopped prior to the surgery [

Mini-heparin and low-dose chemoprophylaxis do not increase size of intraspinal hematoma following spinal cord injury

Following spinal cord injury (SCI), Chang et al. (2017) compared the frequency of intraspinal hemorrhage for 241 patients on early chemoprophylaxis vs. 241 patients not placed on early prophylaxis (e.g., mini-heparin, LD-ASA) for deep venous thrombosis ([DVT]/pulmonary embolism [PE]). [

CONCLUSIONS

Multiple studies demonstrated the relative increased hemorrhagic risks/complications of performing spinal surgery while continuing LD-ASA or just stopping LD-ASA for 3–7 days prior to SS; notably, several other studies also indicated no such risks if LD-ASA was stopped for >7–10 days [Tables

References

1. Chang R, Scerbo MH, Schmitt KM, Adams SD, Choi TJ, Wade CE. Early chemoprophylaxis is associated with decreased venous thromboembolism risk without concomitant increase in intraspinal hematoma expansion after traumatic spinal cord injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017. 83: 1088-94

2. Cuellar JM, Petrizzo A, Vaswani R, Goldstein JA, Bendo JA. Does aspirin administration increase perioperative morbidity in patients with cardiac stents undergoing spinal surgery?. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015. 40: 629-35

3. Gerstein NS, Schulman PM, Gerstein WH, Petersen TR, Tawil I. Should more patients continue aspirin therapy perioperatively.: Clinical impact of aspirin withdrawal syndrome?. Ann Surg. 2012. 255: 811-9

4. Kang SB, Cho KJ, Moon KH, Jung JH, Jung SJ. Does low-dose aspirin increase blood loss after spinal fusion surgery?. Spine J. 2011. 11: 303-7

5. Park JH, Ahn Y, Choi BS, Choi KT, Lee K, Kim SH. Antithrombotic effects of aspirin on 1- or 2-level lumbar spinal fusion surgery: A comparison between 2 groups discontinuing aspirin use before and after 7 days prior to surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013. 38: 1561-5

6. Park HJ, Kwon KY, Woo JH. Comparison of blood loss according to use of aspirin in lumbar fusion patients. Eur Spine J. 2014. 23: 1777-82

7. Smilowitz NR, Oberweis BS, Nukala S, Rosenberg A, Stuchin S, Iorio R. Perioperative antiplatelet therapy and cardiovascular outcomes in patients undergoing joint and spine surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2016. 35: 163-9

8. Soleman J, Baumgarten P, Perrig WN, Fandino J, Fathi AR. Non-instrumented extradural lumbar spine surgery under low-dose acetylsalicylic acid: A comparative risk analysis study. Eur Spine J. 2016. 25: 732-9

9. Yang SM, Kang SH, Kim KT, Park SW, Lee WS. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas associated with acute myocardial infarction treatment. Korean Circ J. 2011. 41: 759-62

10. Zhang C, Wang G, Liu X, Li Y, Sun J. Safety of continuing aspirin therapy during spinal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017. 96: e8603-

G...................

Posted October 8, 2019, 4:35 pm

Hopefully this comment will be of use to someone else who comes across this page, in preventing uncritical acceptance of the conclusions. This is an editorial (thankfully clearly marked as such) that has recruited a number of references to appear as a quasi-literature analysis. However, one should note that a) the author does not describe her methods for selection of the referenced articles (moreoever, the “methods” section appears only in the abstract); and as a result, b) the articles discussed may not accurately reflect the comprehensive body of literature on the subject, and may have been selected by the author to support an editorial viewpoint. Furthermore, the amount of discussion allotted to each article is so brief that it must be considered perfunctory. Please treat these conclusions with the appropriate skepticism.

At the time of this comment, the page view counter states nearly 4800. One hopes that does not reflect anything approaching a number of patients treated under advisement of this misleading editorial.