- Stroke Center, Sagamihara Kyodou Hospital, Sagamihara, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Taro Yanagawa, Stroke Center, Sagamihara Kyodou Hospital, Midori-ku, Sagamihara, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_229_2023

Copyright: © 2023 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Taro Yanagawa, Shunsuke Ikeda, Shota Yoshitomi, Aoto Shibata, Toshiki Ikeda. A case of infectious intracranial aneurysm that formed and ruptured within a few days after occlusion of the proximal middle cerebral artery by infective endocarditis. 02-Jun-2023;14:193

How to cite this URL: Taro Yanagawa, Shunsuke Ikeda, Shota Yoshitomi, Aoto Shibata, Toshiki Ikeda. A case of infectious intracranial aneurysm that formed and ruptured within a few days after occlusion of the proximal middle cerebral artery by infective endocarditis. 02-Jun-2023;14:193. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/12343/

Abstract

Background: Embolic cerebral infarction and infectious intracranial aneurysms (IIAs) are well-known central nervous system complications of infective endocarditis (IE). In this report, we describe a rare case of cerebral infarction caused by the occlusion of the M2 inferior trunk due to IE, followed by the rapid formation and rupture of IIA.

Case Description: A 66-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of IE and embolic cerebral infarction after being brought to the emergency department with a 2-day history of fever and difficulty walking. After admission, she was immediately started on antibiotic therapy. Three days later, the patient suddenly became unconscious, and a head computed tomography (CT) scan showed massive cerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Contrast-enhanced CT showed a 13-mm large aneurysm in the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) bifurcation. An emergency craniotomy was performed, and intraoperative findings revealed a pseudoaneurysm at the origin of the M2 superior trunk. Clipping was considered difficult, so trapping and internal decompression were performed. The patient died on the 11th day after surgery due to the worsening of her general condition. The pathology of the excised aneurysm was consistent with a pseudoaneurysm.

Conclusion: IE may cause occlusion of the proximal MCA and rapid formation and rupture of IIA. It should be noted that the location of IIA may be a short distance away from the occlusion site.

Keywords: Infective endocarditis, Pseudoaneurysm, Subarachnoid hemorrhage

INTRODUCTION

Embolic cerebral infarction and infectious intracranial aneurysms (IIAs) are common central nervous system complications of infective endocarditis (IE). Embolic cerebral infarcts caused by IE are often detected as multiple microcortical infarcts, while most IIAs occur in the peripheral portion of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and are often detected as intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage.[

CASE REPORT

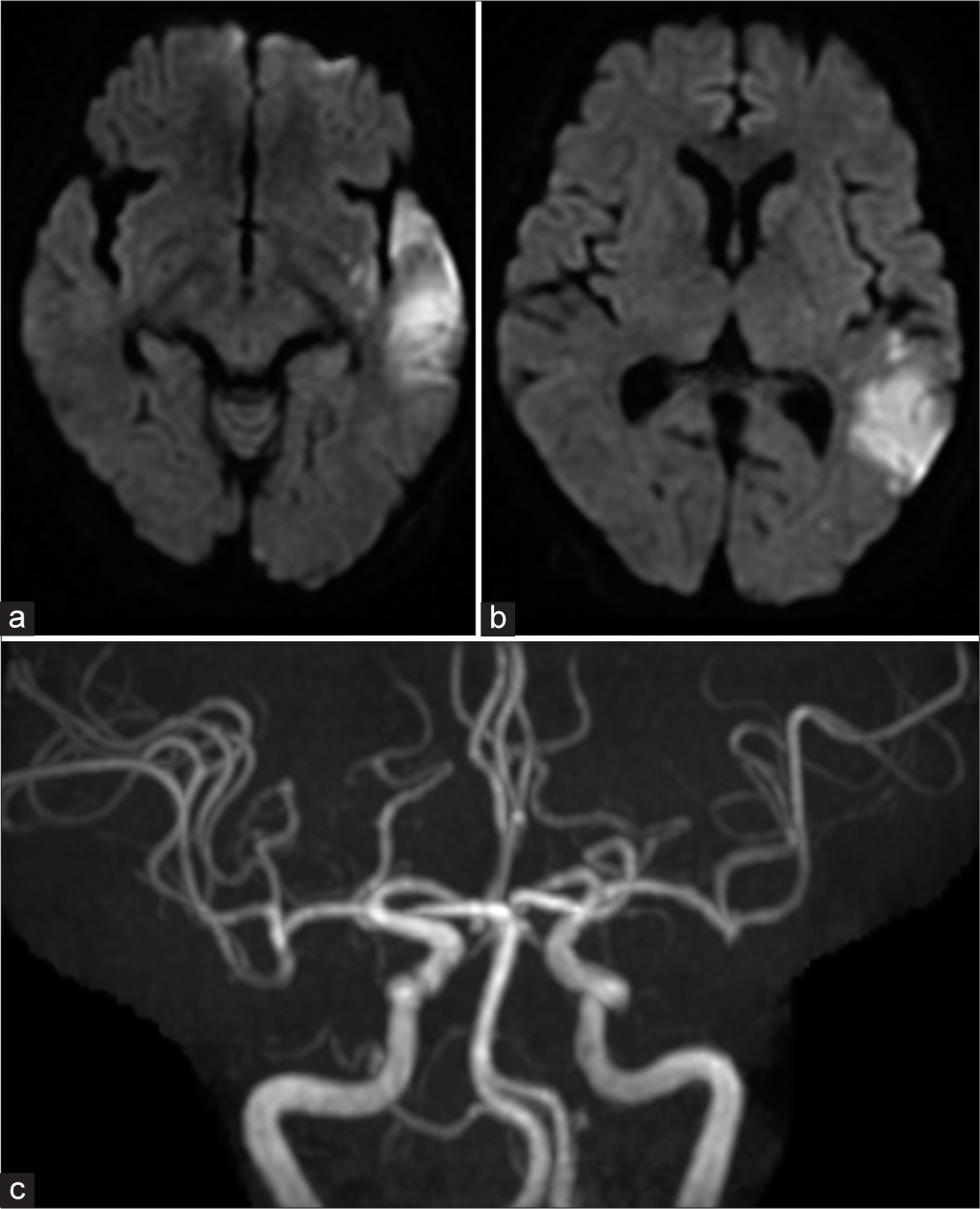

A 66-year-old woman with no pertinent medical history had a 2-day history of high fever. Thereafter, she experienced difficult walking and dysarthria and was rushed to our hospital. A COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction test was negative. She was admitted to the cardiology department with a suspicion of IE because of the presence of a heart murmur as well as valve destruction and vegetation of >10 mm on echocardiography. Immediately after admission, antibiotic therapy was started, and valve replacement was planned. Four sets of blood cultures taken on admission revealed Streptococcus mitis. In addition, head magnetic resonance imaging showed cerebral infarction of the left temporoparietal lobes and occlusion of the left M2 inferior trunk [

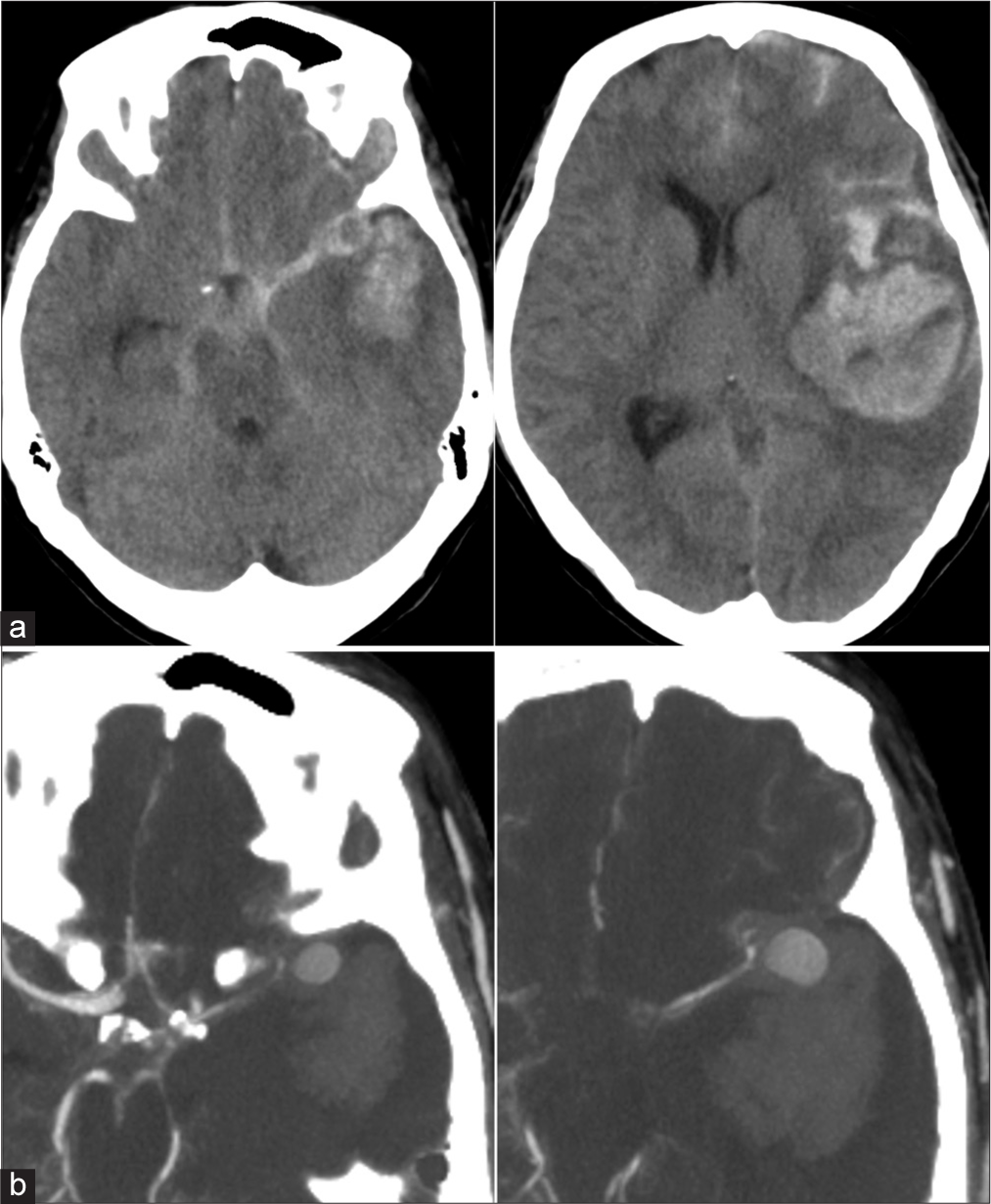

Figure 2:

(a) Preoperative images. Computed tomography images showing subarachnoid haemorrhage and massive cerebral haemorrhage in the left hemisphere. (b) Preoperative images. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography images showing a large aneurysm in the proximal middle cerebral artery. The neck of the aneurysm appears to be lacking.

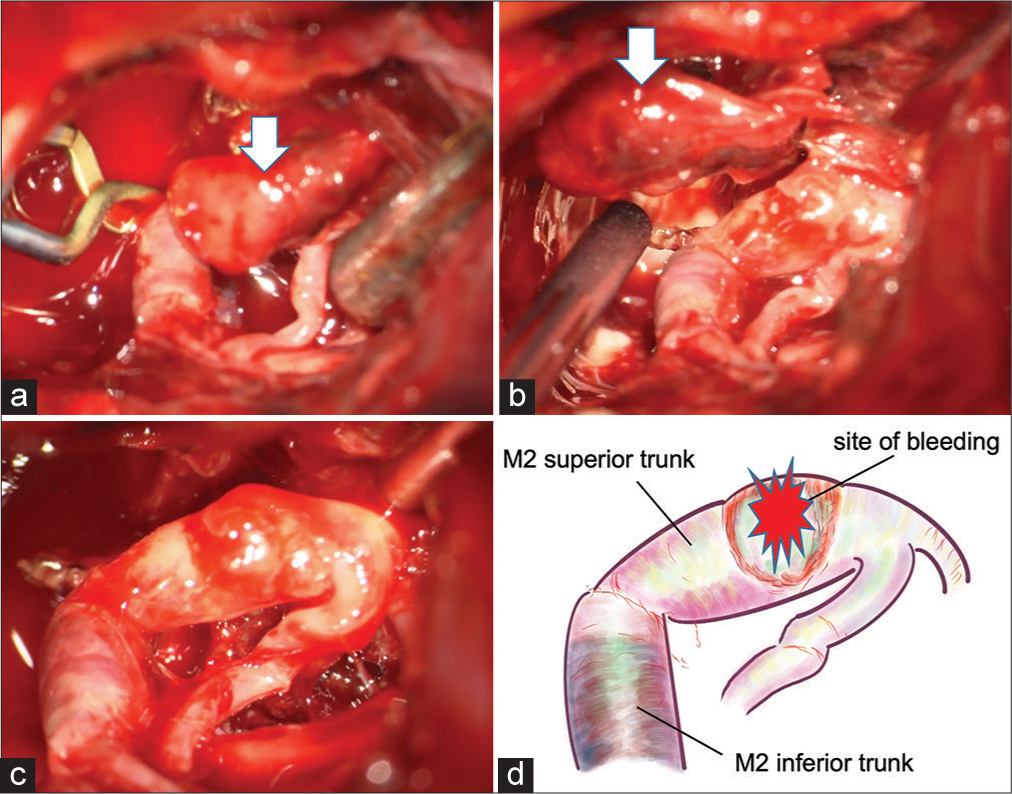

Figure 3:

(a) Intraoperative photograph showing a temporary clip on M1 and a large aneurysm (arrow). (b) There was no continuity between the aneurysm (arrow) and middle cerebral artery. (c) Intraoperative photograph after removal of the aneurysm showing the injured part of the M2 superior trunk and the discolored part of the M2 inferior trunk. (d) An illustration of C.

Operation

A large left frontotemporal craniotomy was performed, and the intracerebral hematoma was removed. An aneurysm-like mass was present near the M1/M2 bifurcation of the MCA, but there was no clear continuity with between the mass and the MCA. The mass was removed and submitted for pathological examination, and the findings were consistent with a pseudoaneurysm. The remaining aneurysm neck was located at the beginning of the M2 superior trunk, and the entire arterial wall had degenerated. Therefore, neck clipping was judged to be impossible, and trapping was performed on the M2 superior trunk. The M2 inferior trunk had a dark red discoloration and was occluded from the origin. Because most of the brain was damaged due to the massive cerebral hemorrhage, a bypass procedure was not performed. Adequate internal decompression of the frontal and temporal lobes was performed.

Postoperative course

There was no rebleeding and the positive effect of decompression was noted on imaging, but there was no improvement in the level of consciousness. The patient died on the 11th postoperative day due to brain damage and systemic complications.

DISCUSSION

This report highlights two important clinical issues. First, IIA may form and rupture within days after an embolic cerebral infarction associated with IE. There are some case reports of subarachnoid hemorrhage after embolic cerebral infarction due to IE, and as in this case, the interval may be less than a few days.[

Vascular occlusion by bacterial emboli is considered a major cause of cerebral aneurysms due to IE. There are two possible mechanisms for their occurrence: the vasa vasorum theory and the embolic theory.[

Second, infected aneurysms may look like saccular aneurysms, but the neck may be very fragile, making neck clipping difficult to perform. IIA located near the Circle of Willis is considered difficult to clip because the neck of the aneurysm is notably fragile or defective.[

In case of occlusion in the proximal MCA, IIA is likely not to form in the occluded artery but in the site of the blood-flow load. Therefore, emergency craniotomy should be performed, with the assumption that a bypass procedure will be required.

CONCLUSION

When proximal MCA occlusion by bacterial emboli occurs, inflammation around the occlusion site may lead to IIA in sites with a high blood-flow load. The formation and rupture of the IIA can occur within a short period of time after bacterial embolization, necessitating prompt contrast-enhanced examination. If IIA is detected, urgent anti-rupture treatment is necessary, under the assumption that a bypass procedure will be needed.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Chapot R, Houdart E, Saint-Maurice JP, Aymard A, Mounayer C, Lot G. Endovascular treatment of cerebral mycotic aneurysms. Radiology. 2002. 222: 389-96

2. Chu VH, Cabell CH, Benjamin DK, Kuniholm EF, Fowler VG, Engemann J. Early predictors of in-hospital death in infective endocarditis. Circulation. 2004. 109: 1745-9

3. Esenkaya A, Duzgun F, Cinar C, Bozkaya H, Eraslan C, Ozgiray E. Endovascular treatment of intracranial infectious aneurysms. Neuroradiology. 2016. 58: 277-84

4. Frazee JG, Cahan LD, Winter J. Bacterial intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1980. 53: 633-41

5. Inoue T, Anzai T, Utsumi Y. Early subarachnoid hemorrhage from a bacterial aneurysm of the middle cerebral artery bifurcation following cerebral infarction caused by a septic embolism: Case report. No Shinkei Geka. 2006. 34: 1051-5

6. Krapf H, Skalej M, Voigt K. Subarachnoid hemorrhage due to septic embolic infarction in infective endocarditis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1999. 9: 182-4

7. Molinari GF, Smith L, Goldstein MN, Satran R. Pathogenesis of cerebral mycotic aneurysms. Neurology. 1973. 23: 325-32

8. Saito A, Kawaguchi T, Hori E, Kanamori M, Nishimura S, Sannohe S. Subarachnoid hemorrhage after an ischemic attack due to a bacterial middle cerebral artery dissecting aneurysm: Case report and literature review. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2014. 54: 196-200

9. Salgado AV, Furlan AJ, Keys TF, Nichols TR, Beck GJ. Neurologic complications of endocarditis: A 12-year experience. Neurology. 1989. 39: 173-8

10. Wajnberg E, Rueda F, Marchiori E, Gasparetto EL. Endovascular treatment for intracranial infectious aneurysms. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008. 66: 790-4

11. Wakamoto H, Tomita H, Miyazaki H, Ishiyama N, Akasaka Y. The early hemorrhage and development of a bacterial aneurysm after a cerebral ischemic attack caused by a septic embolism--a case report. No Shinkei Geka. 2001. 29: 415-420

12. Yamaguchi S, Sakata K, Nakayama K, Orito K, Ikeda A, Arakawa M. A surgically treated case with a ruptured bacterial aneurysm of the middle cerebral arterial bifurcation following occlusion. No Shinkei Geka. 2004. 32: 493-9