- Department of Neurosurgery, Gifu University, 1-1 Yanagido, Gifu, Gifu 501-1194, Japan,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Gifu Prefectural General Medical Center, 4-6-1 Noishiki, Gifu, Gifu 500-8717, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_138_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Shoji Yasuda1,2, Kodai Uematsu2, Kentaro Yamashita2, Tatsuya Kuroda2, Satoru Murase2, Morio Kumagai2. A case of segmental arterial mediolysis with subarachnoid hemorrhage due to anterior cerebral artery dissection followed by internal carotid artery dissection. 25-May-2021;12:240

How to cite this URL: Shoji Yasuda1,2, Kodai Uematsu2, Kentaro Yamashita2, Tatsuya Kuroda2, Satoru Murase2, Morio Kumagai2. A case of segmental arterial mediolysis with subarachnoid hemorrhage due to anterior cerebral artery dissection followed by internal carotid artery dissection. 25-May-2021;12:240. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10821/

Abstract

Background: Segmental arterial mediolysis (SAM) causes subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) due to intracranial aneurysm rupture and arterial dissection. We encountered a case of SAM-related SAH due to ruptured dissection of the A1 segment of the anterior cerebral artery concomitant with internal carotid artery (ICA) dissection.

Case Description: A 53-year-old man presented with SAH due to a ruptured right A1 dissecting aneurysm. The aneurysm was trapped; however, 7 days after the onset of SAH, he experienced right hemiparesis and aphasia. Angiography showed left ICA dissection; urgent carotid artery stenting was performed, leading to symptom improvement. Abdominal computed tomography angiography showed aneurysms of the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries. He was diagnosed with SAM based on clinical, imaging, and laboratory findings.

Conclusion: In the acute phase of SAM-related SAH, cerebral ischemia could occur due to both cerebral vasospasm and intracranial or cervical artery dissection.

Keywords: Carotid artery stenting, Segmental arterial mediolysis, Subarachnoid hemorrhage

INTRODUCTION

Segmental arterial mediolysis (SAM) is a relatively rare disease characterized by vascular media necrosis without atherosclerotic changes or inflammation. Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a rare primary symptom of SAM, and careful management of symptomatic vasospasm and fragile vessels is needed. We report a case of SAM-related SAH due to anterior cerebral artery (ACA) dissection followed by ischemic symptoms due to internal carotid artery (ICA) dissection.

CASE REPORT

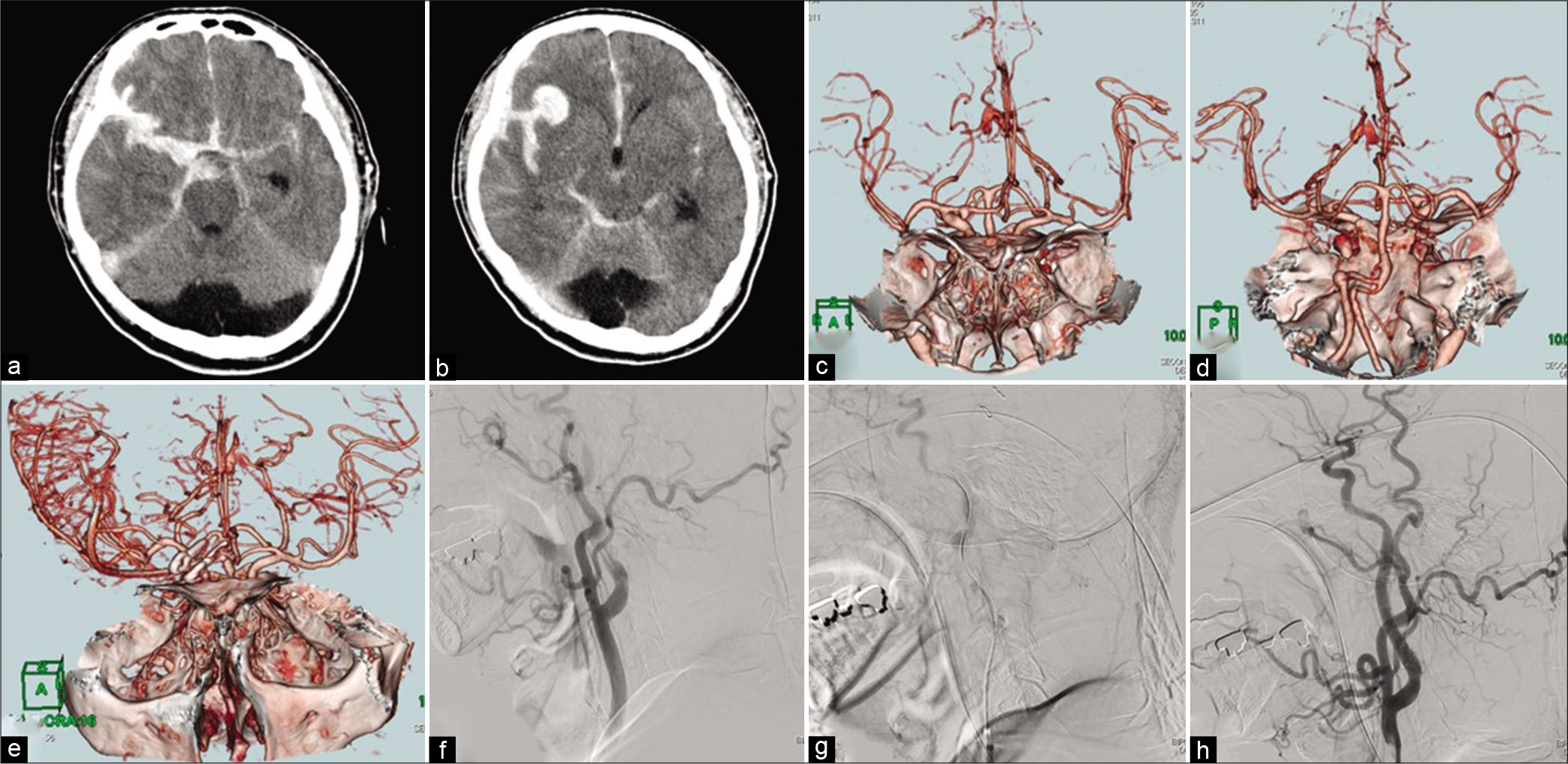

A 53-year-old Japanese man was transferred to our hospital with sudden onset of severe headache and disturbance of consciousness. On admission, his consciousness level was E4V5M6 on the Glasgow Coma Scale and he had no neurological deficits. Head computed tomography (CT) revealed a thick SAH with Sylvian hematoma (Fisher Group 4), and CT angiography (CTA) revealed a fusiform aneurysm of the right A1 segment of the ACA and a saccular aneurysm of the left vertebral artery (VA) [

Figure 1:

(a and b) Head computed tomography (CT) showing thick subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), Sylvian hematoma, and acute hydrocephalus. (c and d) Head CT angiography showing right A1 anterior cerebral artery (ACA) aneurysm with bleb and left vertebral artery saccular aneurysm. (e) Head CT angiography on day 7 after SAH showing trapped right A1 ACA aneurysm. The left middle cerebral artery is visualized less clearly than the right middle cerebral artery. (f) Initial common carotid angiography (CCAG) showing dissection of the cervical portion of the left internal carotid artery with delayed distal flow. (g) Internal carotid angiography from the distal lumen of the dissecting lesion. (h) Postoperative CCAG showing the dissecting lesion after carotid stenting.

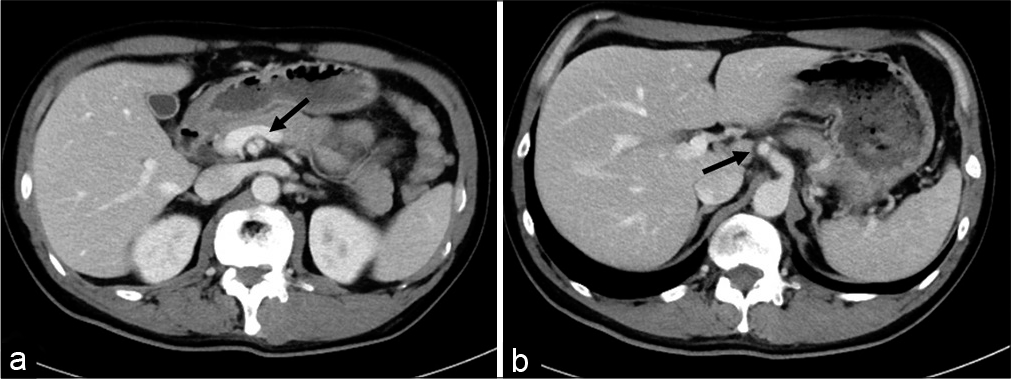

Laboratory results showed that the C-reactive protein level was not elevated, and immunological tests for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and antinuclear antibody were negative. Abdominal CTA showed dissecting aneurysms of the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries [

The patient underwent cranioplasty, and on day 46 after SAH, he was discharged with no neurological deficits. At present, he undergoes regular follow-up imaging to monitor the left VA, celiac artery, and superior mesenteric artery aneurysms.

DISCUSSION

SAM, first described by Slavin et al. in 1976, is a nonatherosclerotic and noninflammatory vascular disease characterized by arterial mediolysis.[

The indications for surgery in patients with SAM have not been determined. If the patient is hemodynamically stable, medical management of pain, hypertension, and vasoconstriction is preferred over surgical treatment.[

No specific strategy for preventing cerebral vasospasm in patients with SAM-related SAH exists. Excessive antihypertensive therapy may lead to cerebral ischemia due to decreased blood flow, and vasodilator or antithrombotic agents increase the risk of hemorrhagic complications. The risk of medial necrosis could be high and the quantity of norepinephrine released is important in determining the extent of mediolysis.[

In this case, systolic blood pressure was maintained below 180 mmHg, hemodynamics and neurological status were strictly monitored, and imaging was regularly performed. Consequently, symptomatic vasospasm did not occur, and no lesion except the left ICA dissection required surgery. If symptomatic vasospasm of a major intracranial trunk occurs in a patient with SAM-related SAH, vasodilator infusion might be safer than percutaneous angioplasty with balloon inflation or stent placement as it avoids mechanical stimulation of the intima or media. However, as seen in this case, decreased cerebral blood flow with vascular lumen narrowing can also be caused by intracranial or cervical artery dissection; therefore, the cause of cerebral ischemia should be carefully identified.

CONCLUSION

We encountered a case of SAM-related SAH due to ruptured A1 segment of the ACA aneurysm and ICA dissection. In the acute phase of SAH, cerebral ischemia could be caused by both cerebral vasospasm and intracranial or cervical artery dissection. Early recognition of SAM is important in patients with multiple arterial dissections, and prompt diagnosis and careful management can lead to a good prognosis. Furthermore, if surgical intervention is needed, it should be performed in a way that avoids injury to other vessels.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Hayashi S, Hosoda K, Nishimoto Y, Nonaka M, Higuchi S, Miki T. Unexpected intraabdominal hemorrhage due to segmental arterial mediolysis following subarachnoid hemorrhage: A case of ruptured intracranial and intraabdominal aneurysms. Surg Neurol Int. 2018. 9: 175

2. Kalva SP, Somarouthu B, Jaff MR, Wicky S. Segmental arterial mediolysis: Clinical and imaging features at presentation and during follow-up. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011. 22: 1380-7

3. Peng KX, Davila VJ, Stone WM, Shamoun FE, Naidu SG, McBane RD. Natural history and management outcomes of segmental arterial mediolysis. J Vasc Surg. 2019. 70: 1877-86

4. Slavin RE, Gonzalez-Vitale JC. Segmental mediolytic arteritis: A clinical pathologic study. Lab Invest. 1976. 35: 23-9

5. Slavin RE. Segmental arterial mediolysis: A review of a proposed vascular disease of the peripheral sympathetic nervous system a density disorder of the alpha-1 adrenergic receptor?. J Cardiovasc Dis Diagn. 2015. 3: 190