- Professor of Clinical Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, State University of NY at Stony Brook and Editor-in-Chief Surgical Neurology International NY, USA, and c/o Dr. Marc Agulnick, 1122 Franklin Avenue Suite 106, Garden City, NY, USA,

- Assistant Clinical Professor of Orthopedics, NYU Langone Hospital, Long Island, NY, USA, 1122 Frankling Avenue Suite 106, Garden City, NY, USA.

Correspondence Address:

Nancy E Epstein, M.D., F.A.C.S., Professor of Clinical Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, State University of NY at Stony Brook, and Editor-in-Chief of Surgical Neurology International NY, USA, and c/o Dr. Marc Agulnick, 1122 Franklin Avenue Suite 106, Garden City, NY, USA.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_957_2023

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Nancy E. Epstein1, Marc A. Agulnick2. Anterior cervical surgery for morbidly obese patients should be performed in-hospitals. 05-Jan-2024;15:2

How to cite this URL: Nancy E. Epstein1, Marc A. Agulnick2. Anterior cervical surgery for morbidly obese patients should be performed in-hospitals. 05-Jan-2024;15:2. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/12698/

Abstract

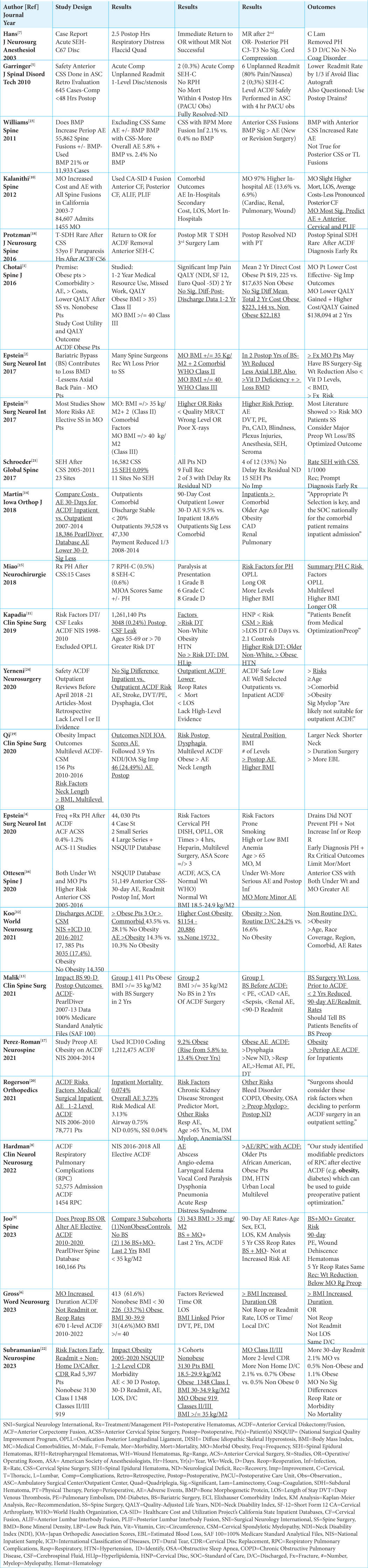

Background: Morbid obesity (MO) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as Class II (i.e. Body Mass Index (BMI) >/= 35 kg/M2 + 2 comorbidities) or Class III (i.e. BMI >/= 40 kg/M2). Here, we reviewed the rates for adverse event/s (AE)/morbidity/mortality for MO patients undergoing anterior cervical surgery as inpatients/in-hospitals, and asked whether this should be considered the standard of care?

Methods: We reviewed multiple studies to document the AE/morbidity/mortality rates for performing anterior cervical surgery (i.e., largely ACDF) for MO patients as inpatients/in-hospitals.

Results: MO patients undergoing anterior cervical surgery may develop perioperative/postoperative AE, including postoperative epidural hematomas (PEH), that can lead to acute/delayed cardiorespiratory arrests. MO patients in-hospitals have 24/7 availability of anesthesiologists (i.e. to intubate/run codes) and surgeons (i.e. to evacuate anterior acute hematomas) who can best handle typically witnessed cardiorespiratory arrests. Alternatively, after average 4-7.5 hr. postoperative care unit (PACU) observation, Ambulatory Surgical Center (ASC) patients are sent to unmonitored floors for the remainder of their 23-hour stays, while those in Outpatient SurgiCenters (OSC) are discharged home. Either for ASC or OSC patients, cardiorespiratory arrests are usually unwitnessed, and, therefore, are more likely to lead to greater morbidity/mortality.

Conclusion: Anterior cervical surgery for MO patients is best/most safely performed as inpatients/in-hospitals where significant postoperative AE, including cardiorespiratory arrests, are most likely to be witnessed events, and appropriately emergently treated with better outcomes. Alternatively, MO patients undergoing anterior cervical procedures in ASC/OSC will more probably have unwitnessed AE/cardiorespiratory arrests, resulting in poorer outcomes with higher mortality rates. Given these findings, isn't it safest for MO patients to undergo anterior cervical surgery as inpatients/in-hospitals, and shouldn't this be considered the standard of care?

Keywords: Anterior Cervical Surgery, Postoperative Epidural Hematomas (PEH), Risks, Adverse Events, Patient Selection, Morbid Obesity (MO), Contraindication Outpatient Surgery, Morbidity/Mortality, Cardiorespiratory Arrests, Witnessed, Unwitnessed

INTRODUCTION

Morbid obesity is defined as Class II (i.e. Body Mass Index >/= 35 kg/M2 + 2 comorbidities) and Class III (i.e. BMI >/= 40) by the World Health Organization (WHO) [

1/1000 to 0.4-1.2% Incidence of Postoperative Spinal Epidural Hematomas (SEH) Following Anterior Cervical Surgery

Two studies looked at varying frequencies of postoperative SEH following anterior cervical surgery (i.e. 1/1000 to 0.4-1.2%) [

Advantages of Inpatient/In-Hospital Treatment for Acute Postoperative Anterior Cervical Hematomas

The protocols for treating acute postoperative anterior cervical hematomas may include; (A) immediate opening of wounds in the postoperative care unit (PACU) (i.e. for patients in severe acute distress, especially where intubation is extremely difficult), and (B) obtaining STAT postoperative MR scans followed by returns to the operating room to remove documented hematomas. Additionally, MO inpatients who develop postoperative AE, especially including increased focal swelling/edema, exacerbation of obstructive sleep apnea, and/or postoperative epidural hematomas (PEH) as inpatients/in-hospital settings, have 24/7 availability of anesthesiologists (i.e., to intubate, run codes and resuscitate), and surgeons (i.e. to evacuate anterior acute hematomas). Alternatively, after typical 4-7.5 hr. postoperative care unit (PACU) observation periods, Ambulatory Surgical Center (ASC) patients are sent to unmonitored floor beds for up to the remaining 23-hour stays, while Outpatient SurgiCenter (OSC) patients are discharged home. For ASC/OSC patients, cardiorespiratory arrests result in more devastating neurological sequelae and/or death (i.e. Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) Data Show Significant Brain Damage for CPR Delayed 4-6 minutes, and High Probability of Brain Damage if Delayed 6-10 minutes).

Two Case Studies of Acute Returns to the Operating Room Without MR Scans Missed Hematomas

Following ACDF, 2 case studies documented how immediate returns to the operating room without postoperative MR scans failed to correctly diagnose the locations of postoperative hematomas [

Patients With Fewer/More Minor Comorbidities Were “Carefully Selected” for ACDF Surgery in ASC/OSC

Several studies showed that patients with fewer/more minor comorbidities were “carefully selected” to undergo ACDF surgery in ASC/OSC, while most with MO/other major comorbidities were typically triaged to undergo ACDF surgery as inpatients [

Definition of Obesity and Morbid Obesity

The World Health Organization defines Obesity as Class II (>/= 35 kg/M2 + 2 comorbidities) vs. Morbid Obesity as Class III (>/= 40 kg/M2: MO World Health Organization) [

Greater Comorbidities in Obese/MO Patients Undergoing ACDF Lead to More Postoperative Adverse Events (AE)/Morbidity/Mortality

Multiple studies documented greater postoperative AE, morbidity, and mortality rates for obese/MO patients undergoing anterior cervical surgery, particularly ACDF [

As National Inpatient Survey (NIS) Databases Showed Increased Risks for Obese Patients Undergoing ACDF Surgery, These Should Be Performed as Inpatients/InHospitals

Two NIS studies documented that obesity increased the frequencies of adverse events following ACDF surgery that should, therefore, be performed as inpatients [

Greater Risks for Postoperative Hematomas in MO Patients Undergoing ACDF

In 2020, Epstein reviewed 11 studies looking at the frequency of postoperative hematomas following anterior cervical surgery (i.e. ACDF, ACF, and anterior cervical spine surgery (ACSS)) [

Obese Patients Undergoing ACDF Typically Exhibited More Preoperative Comorbidities and Perioperative Adverse Event (AE) Requiring More Non-Routine Discharges

When Koo et al. (2021) looked at discharges for 17,385 patients from the National Inpatient (NIS) sample undergoing ACDF for CSM, they found 3035 (17.4%) were obese (i.e., vs. 14,350 who were not obese) [

MO Patients Undergoing ACDF Required Longer Operations But Without Higher Reoperation/ Readmission Rates, Length of Stay (LOS) or Non-Routine Discharges

Gross et al. (2023) performed a 1-level ACDF study that included 670 patients operated on from 2010 to 2022; 413 (61.6%) patients were non-obese (BMI < 30), 226 (33.7%) were obese (BMI 30-39.9), while 31(4.6%) were MO (BMI >/= 40) [

General Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Spine Operations

In 2017, Epstein specifically looked at the increased risks for MO patients (i.e. Classes II and III) with prior histories of bariatric bypasses undergoing different spine operations [

Utilizing PearlDiver Databases, Two Studies Showed Preoperative Bariatric Surgery (BS) Reduced AE/Morbidity/Mortality Rates for MO Patients Undergoing ACDF

Utilizing the PearlDiver Database, two studies showed that performing bariatric surgery in MO patients prior to ACDF decreased their postoperative AE/morbidity/mortality rates [

Higher Risk of Dural Tears (DT) in Obese Patients Undergoing ACDF Excluding OPLL

Using the National Inpatient Sample (NIS 1998-2010) database for 1,261,140 patients undergoing ACDF, excluding those with OPLL, Kapadia et al. (2019) evaluated risk factors contributing to intraoperative DT [

Risk for Respiratory Pulmonary Complications (PRC) After ACDF Surgery and Preoperative Optimization Recommendations

Utilizing the (NIS (National Inpatient Sample Database 2016-2018) including 52,575 elective ACDF procedures, Hardman et al. (2022) found 1454 ACDF-related postoperative Respiratory Pulmonary Complications (RPC) [

Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) Used in Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery Increased AE Rates

Williams et al. (2011) compared the rates of postoperative AE for 55,862 patients undergoing spine fusions; one group of 11,933 patients received BMP (21%), while the remainder did not [

Increased Risks for MO Patients Undergoing 1-2 Level Anterior Cervical Disc Replacement Surgery

Subramanian et al. (2023) looked at risk factors that correlated with early readmissions and non-home postoperative discharges in NSQUIP (National Surgical Quality Improvement Program) patients undergoing 1-2 level anterior cervical disc replacement surgery (CDR) [

CONCLUSION

MO patients (i.e. defined as Class II (BMI >/= 35 kg/M2) or Class III (BMI >/= 40 kg/M2) with their accompanying greater comorbidities exhibited higher perioperative/postoperative morbidity/mortality rates following anterior cervical surgery (i.e., predominantly ACDF). Therefore, shouldn’t anterior cervical procedures performed in MO patients be performed as inpatients, within in-hospital settings?

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patients’ consent not required as patients’ identities were not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Chotai S, Sielatycki JA, Parker SL, Sivaganesan A, Kay HL, Stonko DP. Effect of obesity on cost per quality-adjusted life years gained following anterior cervical discectomy and fusion in elective degenerative pathology. Spine J. 2016. 16: 1342-50

2. Epstein NE. Bariatric bypasses contribute to loss of bone mineral density but reduce axial back pain in morbidly obese patients considering spine surgery. Surg Neurol Int. 2017. 8: 13

3. Epstein NE. More risks and complications for elective spine surgery in morbidly obese patients. Surg Neurol Int. 2017. 8: 66

4. Epstein NE. Frequency, recognition, and management of postoperative hematomas following anterior cervical spine surgery: A review. Surg Neurol Int. 2020. 11: 356

5. Garringer SM, Sasso RC. Safety of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion performed as outpatient surgery. Spinal Disord Tech. 2010. 23: 439-43

6. Gross EG, Laskay NM, Mooney J, McLeod MC, Atchley TJ, Estevez-Ordonez D. Morbid obesity increases length of surgery in elective anterior cervical discectomy and fusion procedures but not readmission or reoperation rates: A cohort study. World Neurosurg. 2023. 173: e830-7

7. Hans P, Delleuze PP, Born JD, Bonhomme VJ. Epidural hematoma after cervical spine surgery. Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2003. 15: 282-5

8. Hardman M, Bhandarkar AR, Jarrah RM, Bydon M. Predictors of airway, respiratory, and pulmonary complications following elective anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2022. 217: 107245

9. Joo PY, Zhu JR, Rilhelm C, Tang K, Day W, Moran J. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion outcomes in patients with and without bariatric surgery-weight loss does make a difference. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2023. 48: 400-6

10. Kalanithi P, Arrigo R, Boakye M. Morbid obesity increases cost and complication rates in spinal arthrodesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012. 37: 982-8

11. Kapadia BH, Decker SI, Boylan MR, Shah NV, Paulino CB. Risk factors for cerebrospinal fluid leak following anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Clin Spine Surg. 2019. 32: E86-90

12. Koo AB, Elsamadicy AA, Sarkozy M, David WB, Reeves BC, Hong CS. Independent association of obesity and nonroutine discharge disposition after elective anterior cervical discectomy and fusion for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. World Neurosurg. 2021. 151: e950-60

13. Malik AT, Noria S, Xu W, Retchin S, Yu ES, Khan SN. Bariatric surgery before elective anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) in obese patients is associated with reduced risk of 90-day postoperative complications and readmissions. Clin Spine Surg. 2021. 34: 171-5

14. Martin CT, D’Oro A, Buser Z, Youssef JA, Park JB, Meisel HJ. Trends and costs of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: A comparison of inpatient and outpatient procedures. Iowa Orthop J. 2018. 38: 167-76

15. Miao W, Ma X, Liang D, Sun Y. Treatment of hematomas after anterior cervical spine surgery: A retrospective study of 15 cases. Neurochirurgie. 2018. 64: 166-70

16. Ottesen TD, Malpani R, Galivanche AR, Zogg CK, Varthi AG, Grauer JN. Underweight patients are at just as much risk as super morbidly obese patients when undergoing anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine J. 2020. 20: 1085-95

17. Perez-Roman RJ, McCarthy D, Luther EM, Lugo-Pico JG, Leon-Correa R, Gaztanaga W. Effects of body mass index on perioperative outcomes in patients undergoing anterior cervical discectomy and fusion surgery. Neurospine. 2021. 18: 79-86

18. Protzman NM, Kapun J, Wagener C. Thoracic spinal subdural hematoma complicating anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: Case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016. 24: 295-9

19. Qi M, Xu C, Cao P, Tian Y, Chen H, Liu Y. Does obesity affect outcomes of multilevel ACDF as a treatment for multilevel cervical spondylosis?: A retrospective study. Clin Spine Surg. 2020. 33: E460-5

20. Rogerson A, Aidlen J, Mason A, Pierce A, Tybor D, Salzler MJ. Predictors of inpatient morbidity and mortality after 1-and 2-level anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion based on the national inpatient sample database from 2006 through 2010. Orthopedics. 2021. 44: e675-81

21. Schroeder GD, Hilibrand AS, Arnold PM, Rish DE, Wang JC, Gum JL. Epidural hematoma following cervical spine surgery. Global Spine J. 2017. 7: 120S-6

22. Subramanian T, Shinn D, Shahi P, Akosman I, Amen T, Maayan O. Severe obesity is an independent risk factor of early readmission and nonhome discharge after cervical disc replacement. Neurospine. 2023. 20: 890-8

23. Williams BJ, Smith JS, Fu KM, Hamilton DK, Polly DW, Ames CP. Does bone morphogenetic protein increase the incidence of perioperative complications in spinal fusion? A comparison of 55,862 cases of spinal fusion with and without bone morphogenetic protein. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011. 36: 1685-91

24. Yerneni K, Burke JF, Chunduru P, Molinaro AM, Riew KD, Traynelis VC. Safety of outpatient anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2020. 86: 30-45