- Department of Neurosurgery, Moriyama Memorial Hospital, Tokyo, Japan.

- Hypothalamic and Pituitary Center, Moriyama Neurosurgical Center Hospital, Tokyo, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Masahiro Hirayama, Department of Neurosurgery, Moriyama Memorial Hospital, Edogawa City, Tokyo, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_131_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Masahiro Hirayama1, Atsushi Ishida1, Naoko Inoshita1, Hideki Shiramizu1, Haruko Yoshimoto1, Masataka Kato1, Satoshi Tanaka1, Seigo Matsuo1, Nobuhiro Miki2, Masami Ono2, Shozo Yamada2. Apoplexy in sellar metastasis from papillary thyroid cancer: A case report and literature review. 17-Jun-2022;13:253

How to cite this URL: Masahiro Hirayama1, Atsushi Ishida1, Naoko Inoshita1, Hideki Shiramizu1, Haruko Yoshimoto1, Masataka Kato1, Satoshi Tanaka1, Seigo Matsuo1, Nobuhiro Miki2, Masami Ono2, Shozo Yamada2. Apoplexy in sellar metastasis from papillary thyroid cancer: A case report and literature review. 17-Jun-2022;13:253. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11660/

Abstract

Background: Pituitary metastasis from papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) is rare and only a few cases have been reported.

Case Description: We report the case of a patient who presented with visual dysfunction and panhypopituitarism. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a pituitary tumor and hydrocephalus. Transsphenoidal surgery had been indicated, but his surgery had been postponed due to COVID-19 pandemic. During that waiting period, he showed pituitary apoplexy with consciousness disturbance, resulting in acute adrenal insufficiency and diabetes insipidus. He was urgently hospitalized and underwent transsphenoidal surgery. Rapid and permanent pathological examinations have confirmed metastasis of PTC to the pituitary. The patient also underwent serial thyroidectomy. He was also suspected to have secondary hydrocephalus and underwent lumboperitoneal shunting after excluding cerebrospinal fluid metastasis. Thereafter, his cognitive dysfunction and performance status improved dramatically.

Conclusion: To the best of our knowledge, this is the first patient with PTC who developed pituitary apoplexy secondary to metastasis.

Keywords: Case report, Papillary thyroid cancer, Pituitary apoplexy, Pituitary metastasis, Transsphenoidal surgery

INTRODUCTION

Thyroid carcinoma accounts for only 2–4.1% of primary tumors.[

CASE REPORT

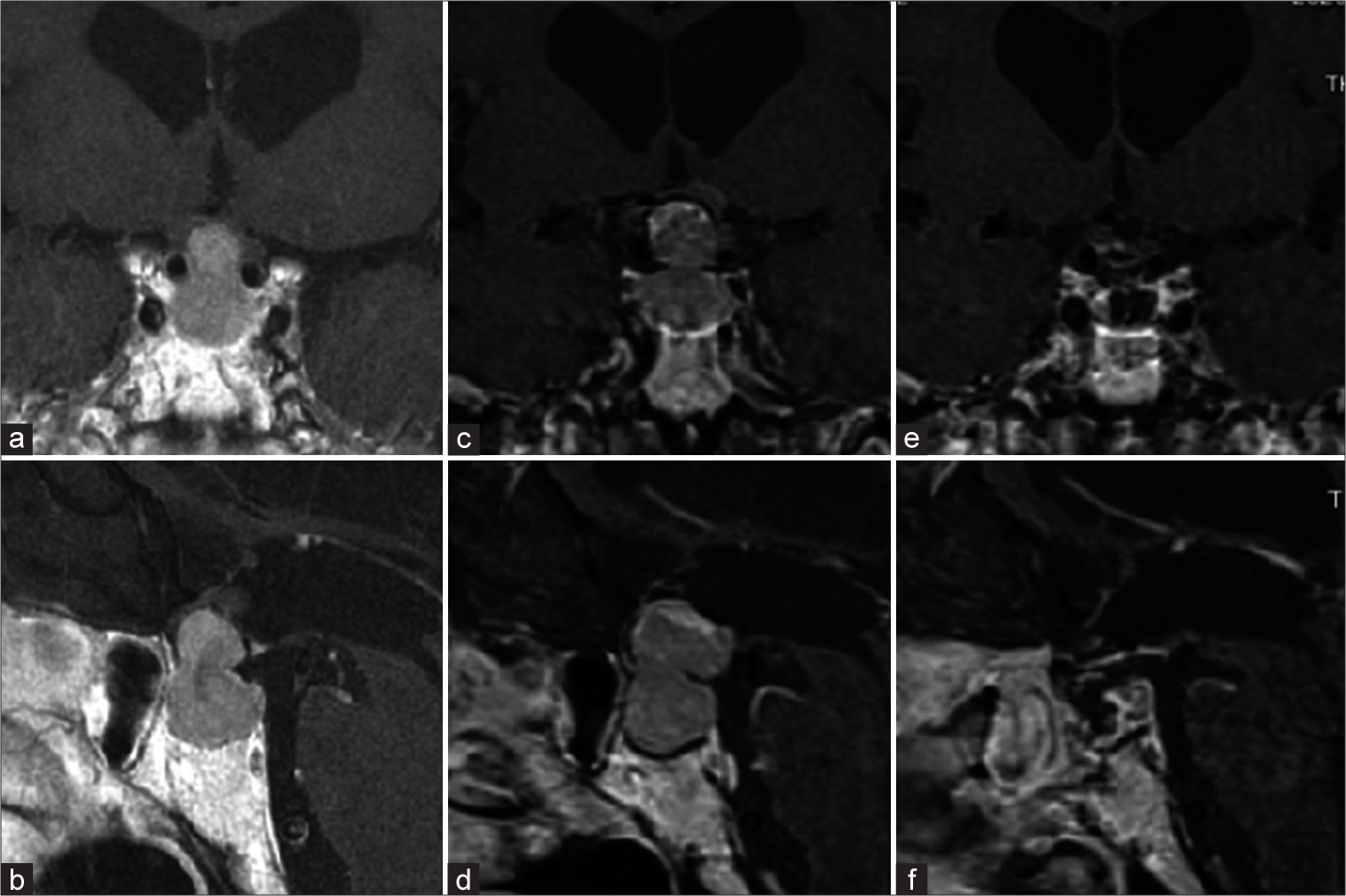

A 74-year-old man without notable medical history and family history who noticed a visual disturbance 3 years prior had extreme tiredness and sought medical care at a different hospital. After a detailed examination, bitemporal hemianopia and panhypopituitarism without DI were noted. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a dumbbell-shaped tumor (22 × 17 × 11 mm) pushing the optic chiasm upward and unobstructed hydrocephalus [

We performed an extended transsphenoidal surgery. The pituitary gland was thin and located in front of the tumor. The upper part of the tumor showed hemorrhagic changes consistent with apoplexy. The tumor was highly vascularized, unlike pituitary adenoma, and adhered tightly to the ventral part of the optic chiasm. The floor of the third ventricle was torn and the contents had leaked. Rapid diagnosis during surgery was suspicious of PTC, and due to the position of the tumor, we decided to retain the tumor capsule. MRI after surgery showed satisfactory decompression [

After surgery, his visual symptoms improved. He underwent whole-body CT scan screening, which detected small lesions in the lung other than the thyroid mass. His serum thyroglobulin was abnormally high (1540 ng/mL) before surgery and decreased to 36.3 ng/mL after surgery. He then developed meningitis and hyponatremia due to cerebral salt-wasting syndrome, which was medically treated.

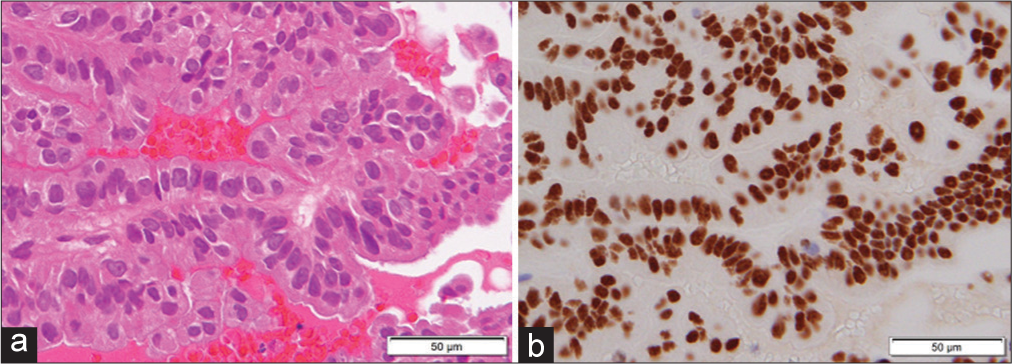

Histological examination of the resected tumor confirmed PTC. An immunohistochemical test reported positive TTF1 and 25% MIB-1 [

He was transferred to another hospital for further treatment of thyroid cancer. He underwent left-sided thyroidectomy and lymphadenectomy, and near-total resection was achieved. The pathological diagnosis was PTC (31 × 22 mm) that had invaded the surrounding muscle (pEx1, pT3b, and pN1b).

123I-iodoamphetamine single-photon emission computed tomography (IMP-SPECT) was performed for further evaluation of his cognitive dysfunction, which showed decreased signal mainly in the frontal lobe and was suspicious of hypothyroidism, hyponatremia, or other metabolic dysfunction disorders and not typical for hydrocephalus or Alzheimer’s disease.

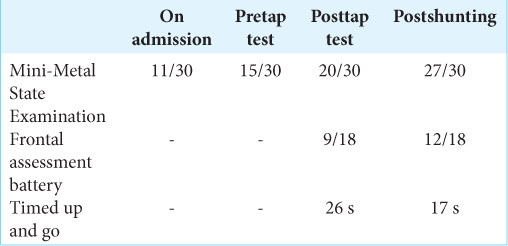

The patient returned to our hospital with prolonged cognitive dysfunction. The tap test was performed. The CSF opening pressure was 19 cm H2O and he showed mild cognitive improvement the following day. The patient underwent lumboperitoneal (LP) shunt placement. Thereafter, his cognitive function recovered dramatically [

DISCUSSION

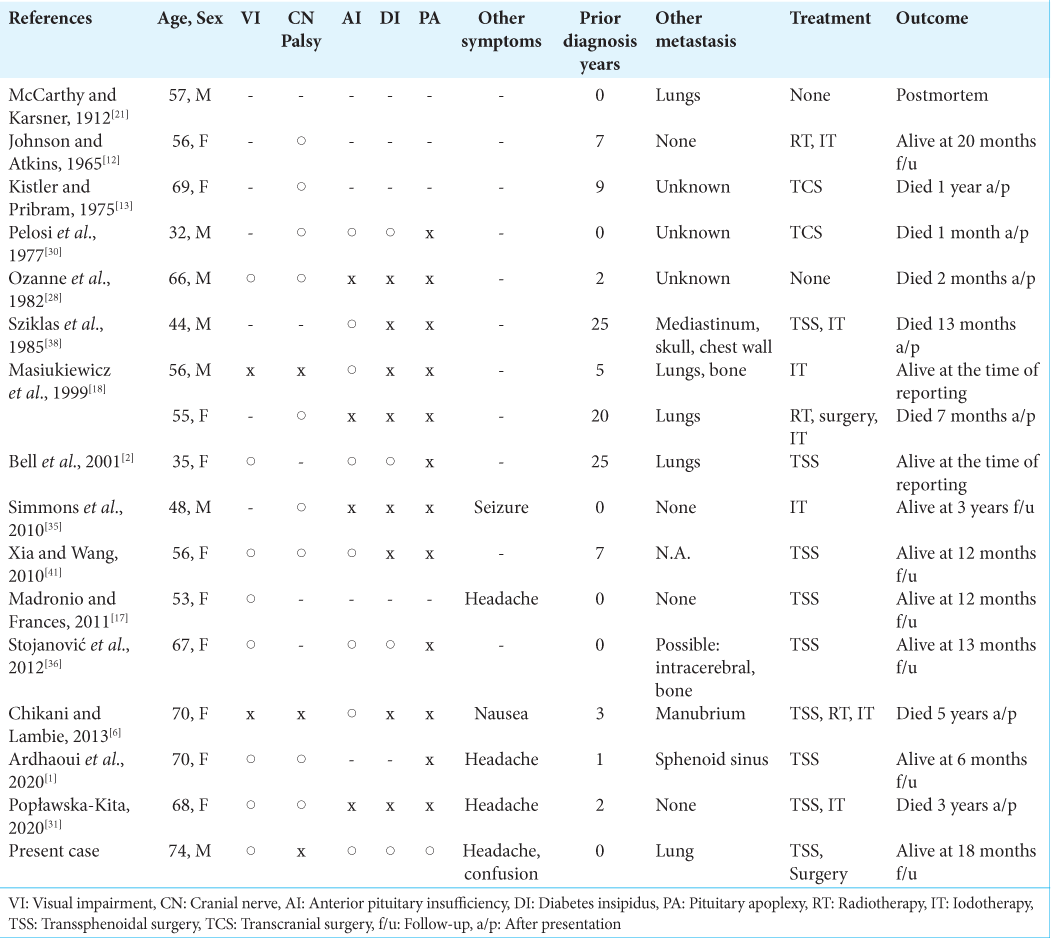

Thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine malignancy; PTC accounts for 80% and is known for its good prognosis. Distant metastasis occurs in about 8% of PTC cases, but pituitary metastasis is extremely rare. Patients exhibit symptoms due to mass effects, such as visual impairment from compression of the optic nerve, ophthalmoplegia of the oculomotor nerve, trochlear nerve, abducens nerve invasion, anterior pituitary insufficiency, and DI.[

The reported poor prognostic factors of distant metastatic PTC are advanced age, distant metastasis from areas other than the lung, and degree of extrathyroidal invasion of the primary neoplasm.[

Treatment options for pituitary metastasis from PTC include transcranial surgery, transsphenoidal surgery, radiotherapy, and iodotherapy, usually for local symptom management because there is no evidence of improvement in life expectancy.[

Preoperative diagnosis of metastatic tumors is challenging. Imaging can support the diagnosis of pituitary tumors. Dutta et al. reported that metastatic lesions tend to destroy the sellar floor and are less likely to destroy the sellar diaphragm.[

DI is a rare manifestation of benign pituitary gland tumors. DI occurs in 3–23% of patients with pituitary apoplexy[

Verrees et al. postulated that DI occurred as a result of impingement of the inferior hypophyseal artery, which caused diminished perfusion to the posterior lobe, or kinking or pressure on the infundibulum by edematous, hemorrhagic material that impeded transit of antidiuretic hormones from the hypothalamus to the posterior lobe.[

Pituitary apoplexy is a life-threatening event resulting from an acute hemorrhagic or ischemic event.[

The patient’s hydrocephalus was evident before apoplexy. IMP-SPECT can support the diagnosis of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH). Ohmichi et al. reported in 80% of cases, IMP-SPECT for a typical iNPH patient shows convexity apparent hyperperfusion (CAPPAH) sign.[

After the tap test, the patient’s cognitive decline became milder. We implanted an LP shunt. Before surgery, CSF tests showed no signs of metastasis. Considering his cognitive improvement and performance status after LP shunt placement, CSF production or absorption seemed to be affected. Mitsuya et al. reported palliative CSF shunting for leptomeningeal metastasis-related hydrocephalus. In the study, CSF shunt surgery yielded rapid improvement in the performance status of 90.3% of patients.[

CONCLUSION

We present the case of a patient with pituitary metastases from papillary thyroid carcinoma, who did not have a prior diagnosis of and developed pituitary apoplexy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the 16th case of pituitary metastasis from PTC, and the first case of apoplexy reported in the literature. His performance status improved dramatically after extended transsphenoidal surgery, hormonal treatment, and shunting. Finally, it should be noted that this pituitary apoplexy occurred during the period when surgery was postponed due to COVID-19 pandemic.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We also would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

References

1. Ardhaoui H, Halily S, Elkrimi Z, Rouadi S, Roubal M, Mahtar M. Thyroid papillary carcinoma with an insular component metastasizing to the sella turcica and sphenoid sinus: Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020. 67: 254-7

2. Bell CD, Kovacs K, Horvath E, Smythe H, Asa S. Papillary carcinoma of thyroid metastatic to the pituitary gland. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001. 125: 935-8

3. Biousse V, Newman NJ, Oyesiku NM. Precipitating factors in pituitary apoplexy. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001. 71: 542-5

4. Bobinski M, Greco CM, Schrot RJ. Giant intracranial medullary thyroid carcinoma metastasis presenting as apoplexy. Skull Base. 2009. 19: 359-62

5. Chhiber SS, Bhat AR, Khan SH, Wani MA, Ramzan AU, Kirmani AR. Apoplexy in sellar metastasis: A case report and review of literature. Turk Neurosurg. 2011. 21: 230-4

6. Chikani V, Lambie D, Russell A. Pituitary metastases from papillary carcinoma of thyroid: A case report and literature review. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2013. 2013: 130024

7. Daou B, Klinge P, Tjoumakaris S, Rosenwasser RH, Jabbour P. Revisiting secondary normal pressure hydrocephalus: Does it exist? A review Neurosurg Focus 2016. ;. 41: E6

8. Dutta P, Bhansali A, Shah VN, Walia R, Bhadada SK, Paramjeet S. Pituitary metastasis as a presenting manifestation of silent systemic malignancy: A retrospective analysis of four cases. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011. 15: S242-5

9. Glezer A, Bronstein MD. Pituitary apoplexy: Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2015. 59: 259-64

10. Habu M, Tokimura H, Hirano H, Yasuda S, Nagatomo Y, Iwai Y. Pituitary metastases: Current practice in Japan. J Neurosurg. 2015. 123: 998-1007

11. He W, Chen F, Dalm B, Kirby PA, Greenlee JD. Metastatic involvement of the pituitary gland: A systematic review with pooled individual patient data analysis. Pituitary. 2015. 18: 159-68

12. Johnson PM, Atkins HL. Functioning metastasis of thyroid carcinoma in the sella turcica. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1965. 25: 1126-30

13. Kistler M, Pribram HW. Metastatic disease of the sella turcica. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975. 123: 13-21

14. Komninos J, Vlassopoulou V, Protopapa D, Korfias S, Kontogeorgos G, Sakas DE. Tumors metastatic to the pituitary gland: Case report and literature review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004. 89: 574-80

15. Kruljiac I, Cerina V, Pecina HI, Prazanin L, Matic T, Bozikov V. Pituitary metastasis presenting as ischemic pituitary apoplexy following heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Endocr Pathol. 2012. 23: 264-7

16. Luu ST, Billing K, Crompton JL, Blumbergs P, Lee AW, Chen CS. Clinicopathological correlation in pituitary gland metastasis presenting as anterior visual pathway compression. J Clin Neurosci. 2010. 17: 790-3

17. Madronio E, Frances L. The tale of two tumors: An undiagnosed case of papillary thyroid carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011. 2011: bcr0820114604

18. Masiukiewicz US, Nakchbandi IA, Stewart AF, Inzucchi SE. Papillary thyroid carcinoma metastatic to the pituitary gland. Thyroid. 1999. 9: 1023-7

19. Masui K, Yonezawa T, Shinji Y, Nakano R, Miyamae S. Pituitary apoplexy caused by hemorrhage from pituitary metastatic melanoma: Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2013. 53: 695-8

20. Max MB, Deck MD, Rottenberg DA. Pituitary metastasis: Incidence in cancer patients and clinical differentiation from pituitary adenoma. Neurology. 1981. 31: 998-1002

21. McCarthy DJ, Karsner HT. Adenocarcinoma of the thyroid with metastasis to the cervical glands and to the pituitary: A contribution to the pathology of abnormal fat formation. Am J Med Sci. 1912. 144: 834-47

22. McCormick PC, Post KD, Kandji AD, Hays AP. Metastatic carcinoma to the pituitary gland. Br J Neurosurg. 1989. 3: 71-9

23. Mitsuya K, Nakasu Y, Hayashi N, Deguchi S, Takahashi T, Murakami H. Palliative CSF shunting for leptomeningeal metastasis-related hydrocephalus in patients with lung adenocarcinoma: A single-center retrospective study. PLoS One. 2019. 14: e0210074

24. Mohr G, Hardy J. Hemorrhage, necrosis, and apoplexy in pituitary adenomas. Surg Neurol. 1982. 18: 181-9

25. Moller-Goede DL, Brändle M, Landau K, Bernays RL, Schmid C. Re-evaluation of risk factors for bleeding into pituitary adenomas and impact on outcome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011. 164: 37-43

26. Ng S, Fomekong F, Delabar V, Jacquesson T, Enachescu C, Raverot G. Current status and treatment modalities in metastases to the pituitary: A systematic review. J Neurooncol. 2020. 146: 219-27

27. Ohmichi T, Kondo M, Itsukage M, Koizumi H, Matsushima S, Kuriyama N. Usefulness of the convexity apparent hyperperfusion sign in 123I-iodoamphetamine brain perfusion SPECT for the diagnosis of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg. 2019. 130: 398-405

28. Ozanne P, Jedynak CP, Charbonnel B, Derome PJ. Pituitary and hypothalamic metastases: 5 cases (in French). Ann Med Interne (Paris). 1982. 133: 92-6

29. Pearce JM. On the origins of pituitary apoplexy. Eur Neurol. 2015. 74: 18-21

30. Pelosi RM, Romaldini JH, Massuda LT, Reis LC, França LC. Pan-hypopituitarism caused by to sellar metastasis from papilliferous carcinoma of the thyroid gland associated with secondary thrombophlebitis of the cavernous sinus and purulent leptomeningitis (in Portuguese). AMB Rev Assoc Med Bras. 1977. 23: 277-80

31. Popławska-Kita A, Wielogórska M, Poplawski L, Siewko K, Adamska A, Szumowski P. Thyroid carcinoma with atypical metastasis to the pituitary gland and unexpected postmortal diagnosis. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2020. 2020: 190148

32. Ranavir S, Manash BP. Pituitary apoplexy. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011. 15: S188-96

33. Schill F, Nilsson M, Olsson DS, Ragnarsson O, Berinder K, Engström BE. Pituitary metastases: A nationwide study on current characteristics with special reference to breast cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019. 104: 3379-88

34. Shou XF, Wang YF, Li SQ, Wu JS, Zhao Y, Mao Y. Microsurgical treatment for typical pituitary apoplexy with 44 patients, according to two pathological stages. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2009. 52: 207-11

35. Simmons JD, Pinson TW, Donnellan KA, Harbarger CF, Pitman KT, Griswold R. A rare case of a 1.5-mm papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid presenting with pituitary metastasis. Am Surg. 2010. 76: 336-8

36. Stojanović M, Pekić S, Doknić M, Miljić D, Cirić S, Diklić A. What’s in the image? Pituitary metastasis from papillary carcinoma of the thyroid: A case report and a comprehensive review of the literature. Eur Thyroid J. 2013. 1: 277-84

37. Sugitani I, Fujimoto Y, Yamamoto N. Papillary thyroid carcinoma with distant metastases: Survival predictors and the importance of local control. Surgery. 2008. 143: 35-42

38. Sziklas JJ, Mathews J, Spencer RP, Rosenberg RJ, Ergin MT, Bower BF. Thyroid carcinoma metastatic to pituitary. J Nucl Med. 1985. 26: 1097

39. Verrees M, Arafah BM, Selman WR. Pituitary tumor apoplexy: Characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Neurosurg Focus. 2004. 16: e6

40. Wakai S, Fukushima T, Teramoto A, Sano K. Pituitary apoplexy: Its incidence and clinical significance. J Neurosurg. 1981. 55: 187-93

41. Xia J, Wang Y. Papillary thyroid carcinoma metastatic to the pituitary gland: A case report and literature review. J Chin Clin Med. 2010. 2: 116-9