- Department of Neurosurgery, Medical College of Wisconsin, Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Brandon Robert Winston Laing, Department of Neurosurgery, Medical College of Wisconsin, Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_904_2021

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Brandon Robert Winston Laing, Hirad S. Hedayat. Basilar artery incarceration secondary to a longitudinal clivus fracture: A rare and favorable outcome of an often devastating injury. 25-Mar-2022;13:107

How to cite this URL: Brandon Robert Winston Laing, Hirad S. Hedayat. Basilar artery incarceration secondary to a longitudinal clivus fracture: A rare and favorable outcome of an often devastating injury. 25-Mar-2022;13:107. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11481/

Abstract

Background: Clival fractures are a rare traumatic finding and are often the result of high-impact craniofacial trauma. Rarely, longitudinal clival fractures can be associated with incarceration of the basilar artery within the fracture and/or the sphenoid sinus. Of the 12 reported cases of basilar incarceration, 11 of these injuries have proved to be fatal due to pontine infarction. We present a patient with basilar artery incarceration without any neurologic deficits.

Case Description: The case reported is a 17-year-old male who presented after a motor vehicle collision with a linear and longitudinal clival fracture with entrapment of the basilar artery within the sphenoid sinus. Diagnostic subtraction angiography showed a small intimal tear with possible intraluminal thrombus. The patient was started on aspirin and at 3-month post injury had no neurologic deficits.

Conclusion: Basilar artery incarceration is an injury often associated with pontine infarction secondary to basilar artery dissection and/or thrombus developing at the site of entrapment. Our case illustrates a favorable outcome after this injury. Based on these results, antiplatelet therapy may be a viable option for prevention of brainstem infarcts in patients with this injury; however, further prospective studies must be done to assess the overall efficacy and validity of this treatment. There are no established treatment guidelines for this condition. Further research on this topic should also be tailored toward early identification of this pathology and prevention of thromboembolic sequelae of this injury.

Keywords: Basilar artery entrapment, Basilar artery dissection, Clival fracture, Trauma

INTRODUCTION

Clival fractures are a rare traumatic finding and are often the result of high-impact craniofacial injuries. The incidence of these injuries in the literature ranges from 0.6% to 1.2%.[

CASE DESCRIPTION

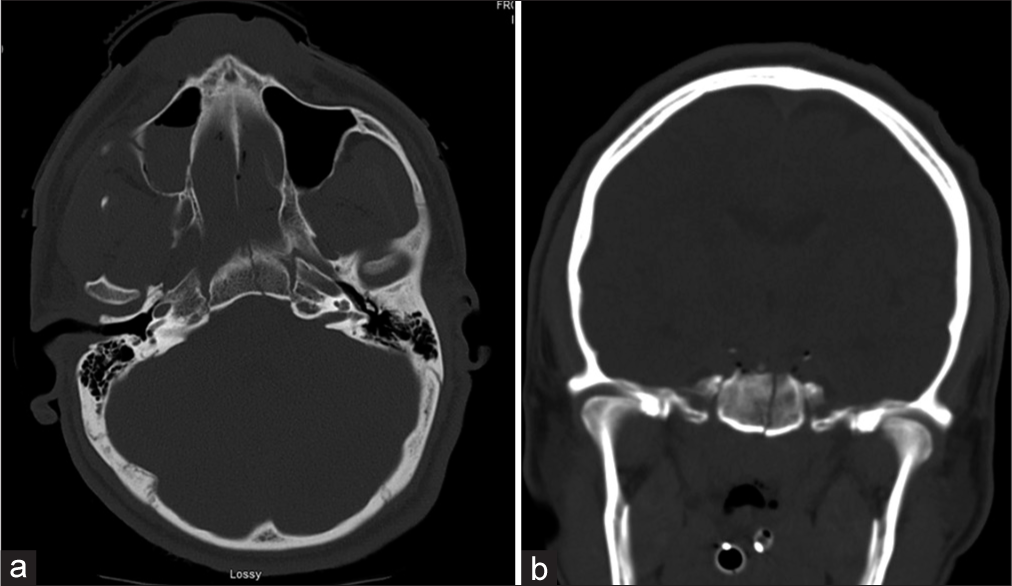

Patient is a 17-year-old male who was the driver in a motor vehicle collision. On presentation, he had a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 6T – intubated, no eye opening, localizing bilateral upper extremities to the central painful stimulus without any weakness, and pupils equally round and reactive to light. Trauma computed tomography (CT) scans revealed a linear, non-displaced longitudinal clival fracture, right frontal and left parietal subdural hematomas, suprasellar and interpeduncular subarachnoid hemorrhage, bilateral maxillary bone fractures, right orbital wall fracture, and C2 hangman’s fracture [

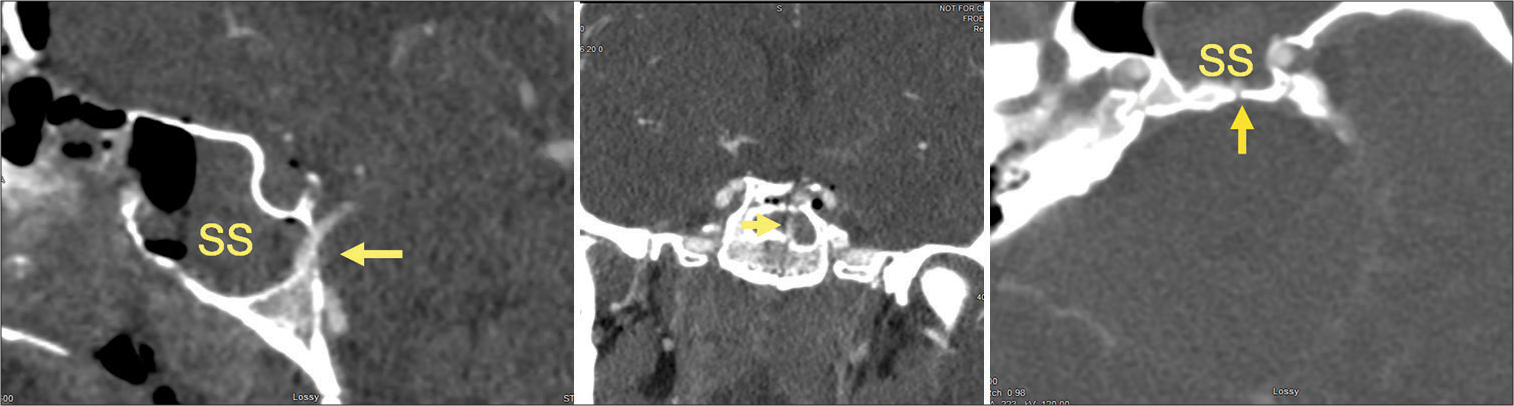

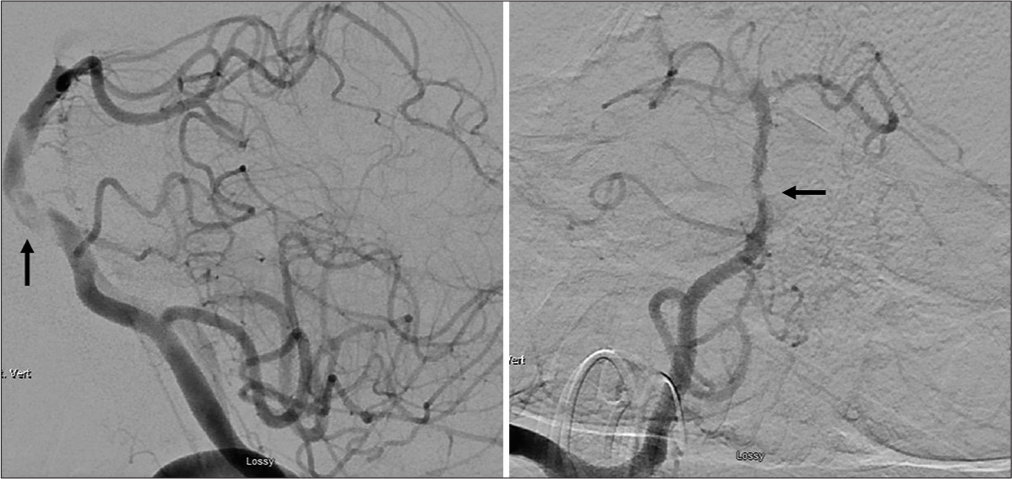

Given his low GCS < 8, an external ventricular drain and Licox monitor were placed the day of admission. Given the cervical spine and clival fractures, CT angiogram of the head-and-neck was obtained. CT angiogram showed herniation of the basilar artery into the sphenoid sinus through the longitudinal basilar skull fracture. The basilar artery had some mild stenosis in the mid-basilar section next to a presumed intimal tear and possible intraluminal thrombus [

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates a rare injury — entrapment of the basilar artery within a longitudinal clival fracture. To the best of our knowledge, there are 12 reported cases of basilar artery incarceration within the literature.[

The earliest suggested mechanism for this injury was reported by Sights in 1967.[

Of the 12 reported cases in the literature, all the patients developed pontine infarctions or cranial nerve palsies. The time to infarction has been variable with evidence of neurological decline anywhere from immediately post injury to up to 48 h afterward. The best reported outcome, to the best of our knowledge, was reported by Bala et al. in 2003.[

Specific guidelines for the management and treatment of this condition have not been established. With respect to nonoperative management in our case, we placed the patient on Aspirin immediately after the diagnosis was established. The decision to start either anti-platelet and/or anticoagulation in this situation is difficult. First, the efficacy of antiplatelet therapy in this case is unclear. There have been patients who have been managed similarly with antiplatelet therapies with variable success.[

There are several factors which may have contributed to this patient’s favorable outcome. First, the patient’s injury was diagnosed early. He underwent CT angiogram within 3 h of presentation which demonstrated the injury. At that time, there was no appreciable thrombus within the basilar artery — only extrinsic compression. Diagnostic catheter angiography within 4 h from his presentation showed only basilar stenosis at the site of the artery herniating into the clivus. In the majority of cases, basilar artery incarcerations happen to be identified after the patient has already had a clinical neurological decline and/or has identifiable strokes on MRI. Finally, the early initiation of aspirin may have played a role in this favorable outcome by decreasing his thromboembolic complication rate associated with the stenosis.

The only other documented case of basilar artery incarceration with an objectively favorable long-term outcome was identified by Bala et al. in 2003 and had two similarities with our case. First, in both cases, the patient’s injury was identified early and they initially presented with a favorable GCS. Second, antiplatelet therapy was started immediately after diagnosis of the basilar artery incarceration. The patient was started on Aspirin at a dose of 100 mg daily. In their case, the patient had a significant neurological decline within 12 h after presentation. However, despite this decline, the patient did make a substantial recovery. Starting antiplatelet therapy early may have prevented further thromboembolic sequelae and/or pontine infarction; however, we are unable to objectively prove this retrospectively. It is also possible that the patient’s young age may have played a role in his overall favorable outcome as was the case with our patient. However, given the rarity of this injury and retrospective nature, we are unable to prove that either of these variables are protective factors.

CONCLUSION

Incarceration of the basilar artery is a severe traumatic finding with potentially devastating neurologic sequelae. This injury is the result of a high speed and high impact mechanism and can ultimately result in brainstem infarction relatively quickly. The majority of patients with this injury do poorly; however, there are a few cases with favorable outcomes. Our case presents a 17-year-old male who presented with basilar artery incarceration without any apparent brainstem infarction who was shortly treated with Aspirin after identification of the injury and at 3-month post injury has not had any neurologic sequelae from his accident. Based on this outcome, antiplatelet therapy may be a viable option for prevention of brainstem infarcts in patients with this injury; however, further studies must be done to assess the overall efficacy of this prophylactic treatment. Unfortunately, there are currently no established treatment guidelines for this condition. Further literature on this topic should be tailored toward early identification of this potential injury and prophylactic treatment to prevent brainstem infarction in patients with basilar artery incarceration.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Anthony DC, Atwater SK, Rozear MP, Burger PC. Occlusion of the basilar artery within a fracture of the clivus. J Neurosurg. 1987. 66: 929-31

2. Bala A, Knuckey N, Wong G, Lee GY. Longitudinal clivus fracture associated with trapped basilar artery: Unusual survival with good neurological recovery. J Clin Neurosci. 2004. 11: 660-3

3. Cho J, Moon CT, Kang HS, Choe WJ, Chang SK, Koh YC. Traumatic entrapment of the vertebrobasilar junction due to a longitudinal clival fracture: A case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2008. 23: 747-51

4. Garcia-Garcia J, Villar-Garcia M, Bad L, Segura T. Brainstem infarct due to traumatic basilar artery entrapment caused by a longitudinal clival fracture. Arch Neurol. 2012. 69: 662-3

5. Kaakaji R, Russel E. Basilar Artery herniation into the sphenoid sinus resulting in pontine and cerebellar infarction: Demonstration by three-dimensional time of flight MR angiography. Am J Neuroradiol. 2004. 25: 1348-50

6. Kanamori F, Yamanouchi T, Kano Y, Koketsu N. Endovascular intervention in basilar artery entrapment within the longitudinal clivus fracture: A case report. Neurol Med Chir. 2018. 58: 356-61

7. Khanna P, Bobinski M. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of a basilar artery herniation into the sphenoid sinus. Skull Base. 2010. 20: 269-73

8. Sato S, Lida H, Hirayama H, Endo M, Ohwada T, Fuji K. Traumatic basal artery occlusion caused by a fracture of the clivus case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2001. 41: 541-4

9. Sights WP. Incarceration of the basilar artery in a fracture of the clivus. Case Report. J Neurosurg. 1968. 28: 588-91

10. Taguchi Y, Matsuzawa M, Morishima H, Ono H, Oshima K, Hayakawa M. Incarceration of the basilar artery in a longitudinal fracture of the clivus: Case report and literature review. J Trauma. 2000. 48: 1148-52

11. Wang A, Wainwright J, Cooper J, Tenner M, Tandon A. Basilar artery herniation into the sphenoid sinus secondary to traumatic skull base fractures: Case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2017. 98: 878.e7-10

12. Winkler-Schwartz A, Correa J, Marcoux J. Clival fractures in a level I trauma center. J Neurosurg. 2015. 122: 227-35