- Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Baylor Scott and White - Temple, Temple, Texas, United States.

- Department of Infectious Disease, Baylor Scott and White - Temple, Temple, Texas, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Randy Dean Volkmer, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Baylor Scott and White - Temple, Temple, Texas, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_443_2023

Copyright: © 2023 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Randy Dean Volkmer1, Mark D. Rahm1, John K. Midturi2. Black disc morphology during routine lumbar discectomy with subsequent diagnosis of enterococcal discitis. 14-Jul-2023;14:243

How to cite this URL: Randy Dean Volkmer1, Mark D. Rahm1, John K. Midturi2. Black disc morphology during routine lumbar discectomy with subsequent diagnosis of enterococcal discitis. 14-Jul-2023;14:243. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/12430/

Abstract

Background: Enterococcus faecalis is reported infrequently as an infectious cause of discitis. In the literature, the diagnosis is commonly made based on the clinical picture coupled with blood cultures, imaging, and tissue cultures.

Case Description: A 62-year-old male with chronic lower back pain underwent lumbar decompression for a lumbar disc. At surgery, the patient had significant black discoloration of the disc material. Later, the cultures demonstrated E. faecalis infectious discitis.

Conclusion: Here is an example of enterococcal lumbar discitis found during a routine lumbar discectomy. As operative cultures revealed E. faecalis, the patient required not one but two operations (i.e., second for seroma/ hematoma due to infection) following which antibiotic therapy eradicated the infection.

Keywords: Black disc, Discectomy, Enterococcal, Infectious discitis

INTRODUCTION

Infectious discitis typically occurs through direct inoculation (i.e., contiguous spread of adjacent infection) or is attributed to hematogenous spread of infection to the disc space.[

CASE PRESENTATION

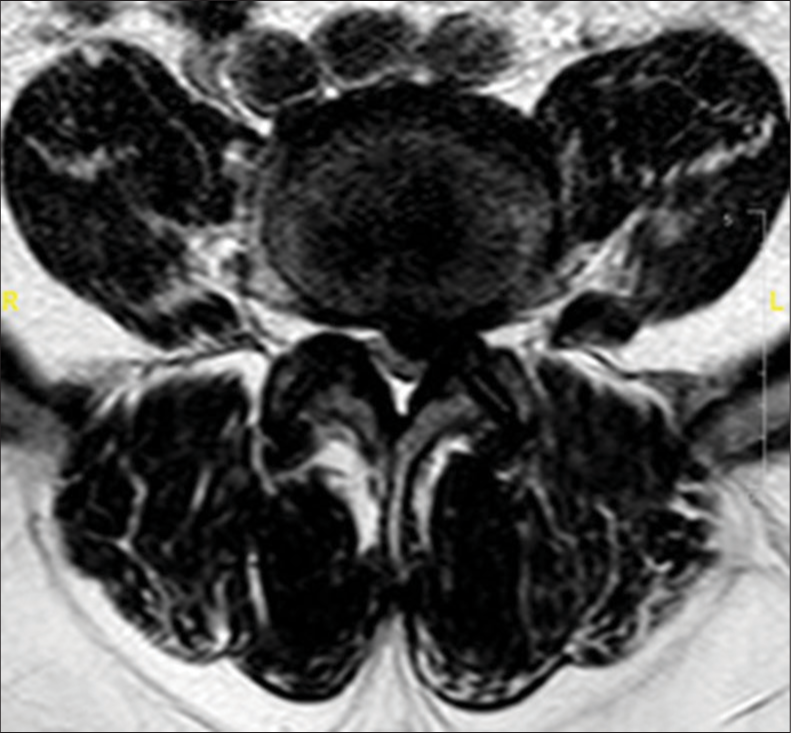

A 62-year-old male presented with back pain and bilateral lower extremity radiculopathy (i.e., left greater than right) without other focal neurological deficits. He had a history of type II diabetes mellitus, obesity, hyperlipidemia, and multiple colon polyps requiring repeated colonoscopies; his last colonoscopy which included a polypectomy had been performed 2 months before the onset of symptoms/complaints. The lumbar magnetic resonance documented a central-left-sided disc protrusion at the L4–L5 level accompanied by severe stenosis at L4–L5, and moderate stenosis at L3–L4 [

Surgery

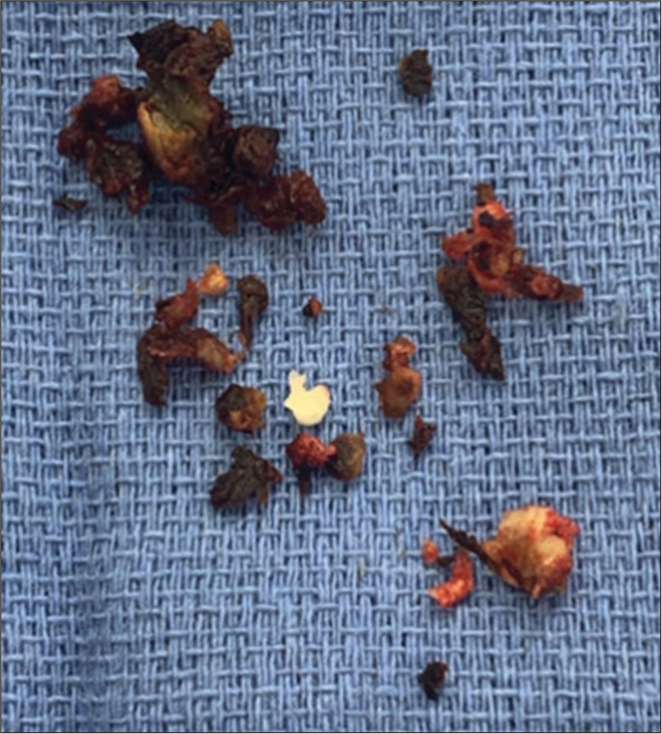

The patient initially underwent a laminectomy from L3 to L5 with a left L4–L5 partial discectomy. At surgery, the removed disc fragments appeared black; there were no accompanying reactive tissue changes or purulence [

Follow-up

Three days later, the culture grew E. faecalis, and the patient was immediately readmitted. On admission, the complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, and blood cultures were negative, but the C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESR) were elevated. Although, the elevated CRP and ESR rates were largely attributed to the recent surgery, he was, nevertheless, empirically placed on vancomycin. Based on subsequent microbiology susceptibility data, this antibiotic was changed to intravenous (IV) ampicillin.

Reoperation

Five days following the initial surgery, the patient underwent a secondary surgery consisting of a wound re-exploration for hematoma. Cultures from the 2nd operation grew a Bifidobacterium spp. At discharge, therefore, the patient was placed on 3 weeks of IV ampicillin followed by 6 months of oral amoxicillin, a regimen that could effectively treat both E. faecalis and Bifidobacterium discitis.

Long-term follow-up

Ten weeks postoperatively, the patient had mild residual low back pain, but the infection had fully resolved. Further, at 4 postoperative months, CRP and ESR values had normalized.

DISCUSSION

Lumbar enterococcal discitis is rare. In the literature, it occasionally occurs in; immunocompromised geriatric patients, those with uncontrolled diabetes, patients with recent genitourinary/gastrointestinal surgery, and/or those on hemodialysis.[

CONCLUSION

Here is an example of enterococcal lumbar discitis found during a routine lumbar discectomy. As operative cultures revealed E. faecalis, the patient required not one but two operations (i.e., second for seroma/hematoma due to infection) following which antibiotic therapy eradicated the infection.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Chew FS, Kline MJ. Diagnostic yield of CT-guided percutaneous aspiration procedures in suspected spontaneous infectious diskitis. Radiology. 2001. 218: 211-4

2. Marella PC, Hasan S, Habte-Gabr E. Report of 2 cases of vertebral osteomyelitis/discitis caused by Enterococcus faecalis in dialysis patients. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2007. 15: 199-200

3. Popescu C, Orfanu A, Leustean A, Orfanu R, Tiliscan C, Arama V. Enterococcus faecalis An unusual etiology of lumbar spondylodiscitis in a patient with chronic kidney disease (undergoing hemodialysis) and sigmoid diverticulosis. Neurol India. 2017. 65: 1393

4. Zimmerli W. Vertebral osteomyelitis. N Engl J Med. 2010. 362: 1022-9