- Department of Neurosurgery, Vydehi Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

Correspondence Address:

Manpreet Singh Banga, Department of Neurosurgery, Vydehi Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1021_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Raj Swaroop Lavadi1, B. V. Sandeep1, Manpreet Singh Banga1, Sangamesh Halhalli1, Anantha Kishan1. Cerebral venous thrombosis with a catch. 30-Nov-2021;12:590

How to cite this URL: Raj Swaroop Lavadi1, B. V. Sandeep1, Manpreet Singh Banga1, Sangamesh Halhalli1, Anantha Kishan1. Cerebral venous thrombosis with a catch. 30-Nov-2021;12:590. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11251/

Abstract

Background: Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is a rare entity typically occurring in patients in hypercoagulable states. They can also occur in cases of trauma. The symptoms are nonspecific.

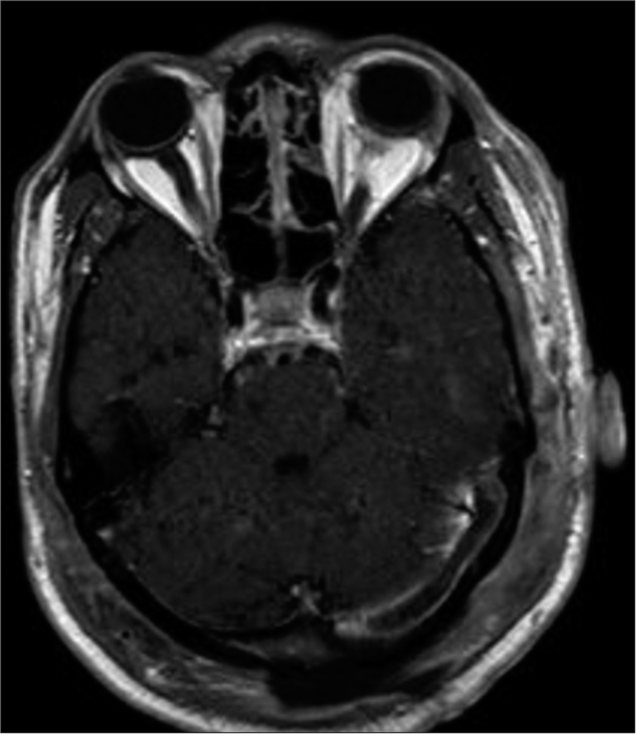

Case Description: A 28-year-old male presented to the emergency department with a head injury. During the necessary imaging, it was found that he had a depressed skull fracture and other signs of traumatic brain injury. Unbeknownst to the patient and the patient party, it was also revealed that the patient only had one kidney. Wound debridement and excision of the depressed fracture were performed. A postoperative MRI revealed that the patient had CVT.

Conclusion: There should be a high index of suspicion for CVT in case of traumatic head injuries. The surgeon should plan management according to the patient’s comorbidities.

Keywords: Cerebral venous thrombosis, Communication, LMWH, Solitary functioning kidney, Trauma

INTRODUCTION

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) accounts for approximately 0.5-3% of all strokes. CVT usually occurs at a lower age than arterial strokes.[

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 28-year-old male presented on a Sunday morning to the emergency department with an alleged history of a road traffic accident after losing control of his two-wheeler. This accident led to an immediate loss of consciousness and headache with vomiting. The patient had a watery discharge from his left ear. There was no history of any bleed or leakage from the nose or history of seizures. He had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13/15 (E3V4M6). On examination, there were two linear lacerations present over his left parieto-occipital region [

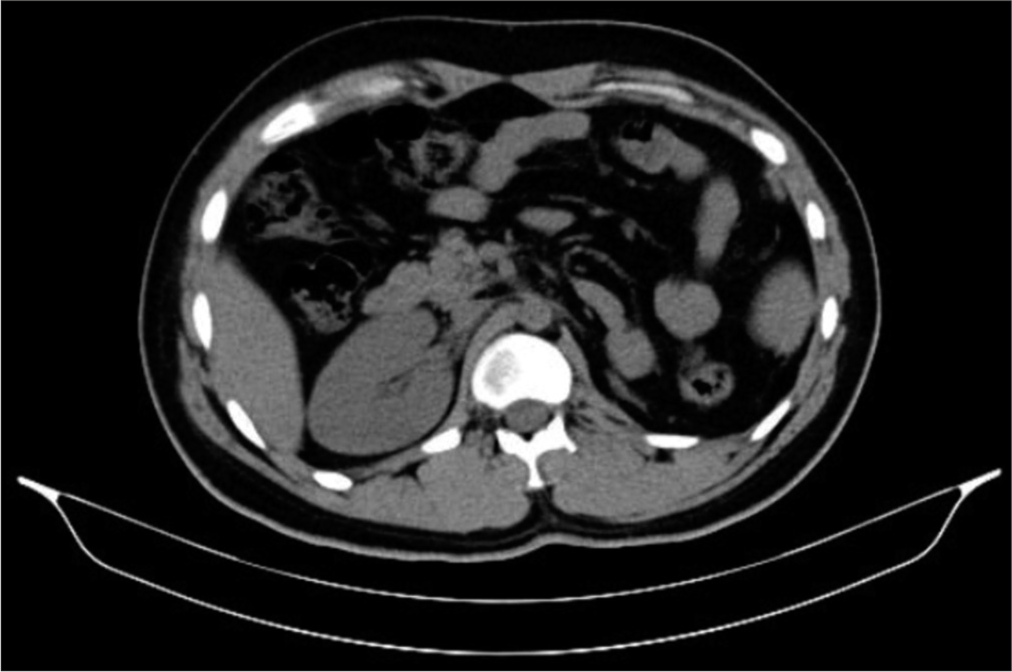

A non-contrast CT brain revealed a left parieto-occipital depressed comminuted fracture with a contusion, hemorrhage, and cephalhematoma. Air pockets were also noted in the left transverse sinus and internal jugular vein, suggestive of traumatic dural venous sinus air. The cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea was attributed to a fracture of the left temporal bone extending to involve the tegmen tympani and the anterior wall of the left external auditory canal. As part of the trauma protocol, a non-contrast abdominal CT was performed, and it showed no internal bleeding but revealed an atrophic left kidney [

Figure 1:

Two deep linear lacerations were present over the left parieto-occipital region. The belly of the temporalis muscle can be visualized in the larger wound. The patient’s history and presentation did not align. It was more probable that the wounds were due to an ax as opposed to a road traffic accident.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of CVT is approximately 3–4/1,000,000.[

The mortality of CVT during the acute stage is 15%.[

CONCLUSION

Intense trauma to the head should necessitate adequate surveillance for CVT. Further research should be carried out to see if there is merit in prophylactically initiating LMWH in patients that have sustained traumatic head injuries in order to reduce the mortality surrounding CVT. Management of the patient should be guided by what is identified throughout the hospital stay. Awareness of the emotions of both the patient and the patient party should be given precedence over the severity of what is being disclosed. This analysis should guide the manner in providing information.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Al-Sulaiman A. Clinical aspects, diagnosis and management of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: A literature review. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2019. 7: 137-45

2. Ghoneim A, Straiton J, Pollard C, Macdonald K, Jampana R. Imaging of cerebral venous thrombosis. Clin Radiol. 2020. 75: 254-64

3. Luo Y, Tian X, Wang X. Diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis: A review. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018. 10: 2

4. Maynard DW. Delivering bad news in emergency care medicine. Acute Med Surg. 2016. 4: 3-11

5. McDonald JS, Katzberg RW, McDonald RJ, Williamson EE, Kallmes DF. Is the presence of a solitary kidney an independent risk factor for acute kidney injury after contrast-enhanced CT?. Radiology. 2016. 278: 74-81

6. So TY, Dixon A, Kavnoudias H, Paul E, Maclaurin W. Traumatic dural venous sinus gas predicts a higher likelihood of dural venous sinus thrombosis following blunt head trauma. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2019. 63: 311-7

7. Tadi P, Behgam B, Baruffi S.editors. Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2021. p.

8. Ulivi L, Squitieri M, Cohen H, Cowley P, Werring DJ. Cerebral venous thrombosis: A practical guide. Pract Neurol. 2020. 20: 356-67

9. Zwart S, van der Wouden EJ, van de Wiel HB, van Leeuwen AJ. Onverwacht goed nieuws na ingrijpende operatie: Een les in communicatie [Unexpected good news after major surgery: A lesson in communication]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2014. 158: A7607