General Neurosurgery

Case Report

- Department of Neurosurgery, Richmond University Medical Center, Staten Island, United States

- Department of Neurosurgery, Wyckoff Heights Medical Center, Brooklyn, United States

Correspondence Address:

Radwa Abbas, Department of Neurosurgery, Wyckoff Heights Medical Center, Brooklyn, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_180_2024

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Erico R. Cardoso1,2, Radwa Abbas2, Emily M. Stone1, Shivali Patel1. Combined pterional burr hole and coagulation of middle meningeal artery for chronic subdural hematoma. 26-Jul-2024;15:254

How to cite this URL: Erico R. Cardoso1,2, Radwa Abbas2, Emily M. Stone1, Shivali Patel1. Combined pterional burr hole and coagulation of middle meningeal artery for chronic subdural hematoma. 26-Jul-2024;15:254. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/combined-pterional-burr-hole-and-coagulation-of-middle-meningeal-artery-for-chronic-subdural-hematoma/

Abstract

Background: There are many surgical techniques to treat chronic subdural hematomas (CSHs). However, they all have high recurrence rates. Recently, embolization of the middle meningeal artery (MMA) following surgical evacuation of CSH has reduced the recurrence rate. We investigated the feasibility of combining the surgical obliteration of the MMA at the same time as the placement of a burr hole for evacuation of the CSH.

Case Description: We report on nine patients who underwent 11 of these combined procedure by the same surgeon in two hospitals, including clinical data and images during the perioperative and postoperative periods. Cardoso had previously reported details of the surgical technique. Two patients underwent bilateral procedures. Two patients had two burr holes because the hematomas did not extend caudally to the pterion, where the MMA enters the calvarium. Intraoperative fluoroscopy was used to locate the point of entry of the MMA into the calvarium in most cases, except in two instances when navigation was utilized.

Conclusion: This small series of nine cases suggests the feasibility of using this combined procedure as an additional option to the treatment of CSHs, especially where endovascular treatment might not be readily available. Furthermore, it has the potential advantages of safety, efficacy, avoidance of a second endovascular procedure, faster disappearance of the subdural collection, lesser exposure to radiation, and cost containment. Larger prospective controlled series are needed to identify its potential usefulness.

Keywords: Arterial coagulation, Burr hole, Chronic subdural hematoma, Middle meningeal artery, Subdural recurrence

INTRODUCTION

We had previously reported a clinical case to demonstrate the feasibility of a modified surgical technique for drainage of chronic subdural hematomas (CSHs). It involved the strategic placement of a pterional burr hole at the origin of the intracranial portion of the middle meningeal artery (MMA), thus allowing drainage of the hematoma with simultaneous coagulation of the MMA.[

CASE DESCRIPTION

This is a retrospective review of 11 procedures performed on nine patients by the same surgeon between January 2019 and December 2022 in two separate hospitals [

Description of the surgical procedure

The surgical procedure has been described in detail with the first patient reported in the literature.[

External surface landmark measurements: The point where a 3.5-cm line from the posterior edge of the superior portion of the zygomatic process of the frontal bone intersects with a 5.5-cm line drawn from the external acoustic meatus (here referred to as the zygomatic-meatal angle) as previously described.[

The correct location is then confirmed by intraoperative lateral fluoroscopy of the skull and by placing a metallic marker at the tip of the zygomatic-meatal angle: this allows clear visualization of the greater sphenoidal wing and the groove of the MMA with its bifurcation at the calvarial entry point. It is easily possible to separate the contralateral equivalent features by tilting the fluoroscopy exposure.

After preparation of the surgical field, the scalp and temporalis muscle are infiltrated with local anesthesia, and a 3.5-cm coronal incision is centered at the middle meningeal calvarial entry point. The temporalis muscle fascicles are bluntly retracted sideways along its fibers, then held by a 2-prong Weitlaner 4” self-retaining retractor. A small burr hole is then fashioned using a match-stick drill bit, which allows the visualization and bipolar coagulation of the branches of the MMA at its bifurcation before opening the dura mater [

The evacuation of the hematoma is then carried out in standard fashion. The operating table can be tilted, if needed, to drain distal portions of the hematoma by the use of gravity gradients. If desired, washing off residual blood by means of a red rubber catheter can also be done. The small surgical wound is then closed in layers.

On only two occasions, navigation was used to locate the MMA, details of which are provided below (cases 2 and 3).

Case 1

This was an 80-year-old right-handed male who presented with mental confusion and imbalance following a fall with a head strike. Four weeks previously, the patient had undergone a left frontal burr hole and right craniotomy simultaneously for evacuation of bilateral subdural hematomas elsewhere, with satisfactory clinical response and postoperative images.

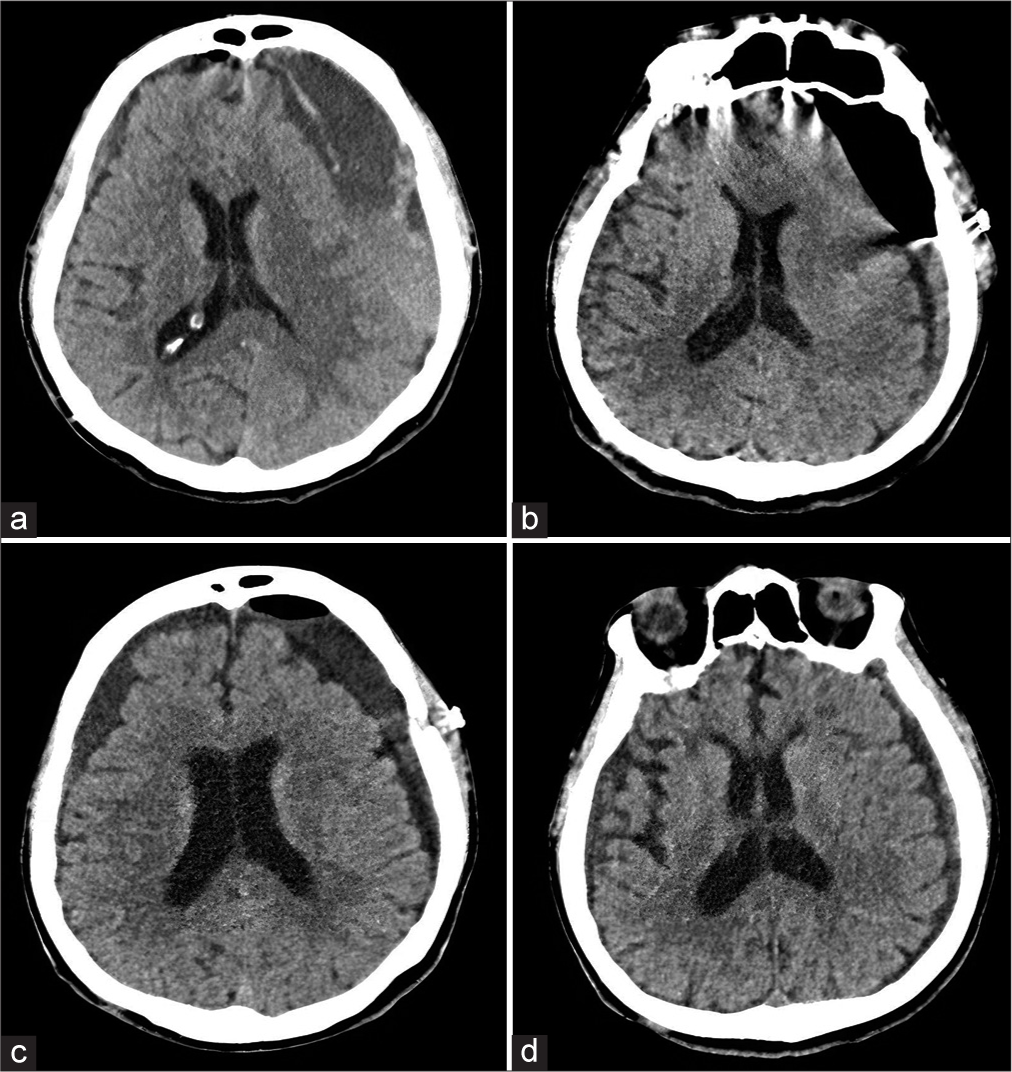

On neurological examination, the patient was alert and confused, only orientated to name and with mild right hemiparesis. The computed tomography (CT) scan of the head showed recollections of bilateral subdural hematomas, much larger on the left, producing a mass effect and left-to-right midline shift [

Evacuation of the recurrent left subdural hematoma was accomplished by performing a left pterional burr hole with coagulation of the MMA, according to the technique described above. Due to a lack of cooperation, the procedure was performed under general anesthesia with the head in skeletal fixation.

Postoperatively, the patient improved quickly. On the 1st postoperative day, his speech became increasingly coherent and the right hemiparesis resolved. The patient was fully alert and oriented by postoperative day 2. At 1 month follow-up, the patient continued to show improvements of balance and only occasional mild episodes of confusion. Sequential postoperative CT scans performed on days 1, 8, and 9 weeks after surgery demonstrated progressive resolution of the subdural collections [

Case 2

This was a 63-year-old female admitted after a suicidal attempt by ingestion of 14 tablets of Ambien. She reported a fall downstairs 5 weeks previously when she hit her head against the heater, sustaining two scalp lacerations. She then developed increasing headaches, dizziness, and depression. The neurological examination was normal, except for slight weakness of bilateral intrinsic hand muscles and mild weakness of the right knee extension, with bilateral patellar hyperreflexia. At 5 weeks post-injury, the patient continued to complain of headaches, photophobia, and dizziness and was started on a trial of oral steroids, with no improvement of symptoms and findings on examination. The patient demanded general anesthesia. The procedure was carried out according to the previous description, except for the use of frameless stereotaxy navigation for the location of the point of entry of the MMA to the calvarium, as the placement of the burr hole at the calvarial entry of the MMA can also be identified by frameless navigation if desired [

The symptoms disappeared immediately after the procedure, and the patient returned to normal activities within 2 weeks. Sequential CT scans showed the disappearance of the subdural collection by 4 weeks [

Case 3

This was a 77-year-old right-handed man who presented with headaches and dizziness following a fall backwards down one flight of stairs, with a head strike and without loss of consciousness.

On examination, the patient was awake and oriented times 3, with a left occipital scalp contusion and hematoma. Cranial nerves were intact, and there were no motor or sensory abnormalities.

The head CT scan showed bifrontal lobe contusions, pneumocephalus, left medial maxillary wall fracture, a linear fracture of the left occipital bone, and chronic bilateral subdural collections. The latter had increased in size when compared to magnetic resonance imaging 9 months previously. Repeat imaging revealed an increase in the size of the subdural collections, especially on the right, accompanied by increasing headaches [

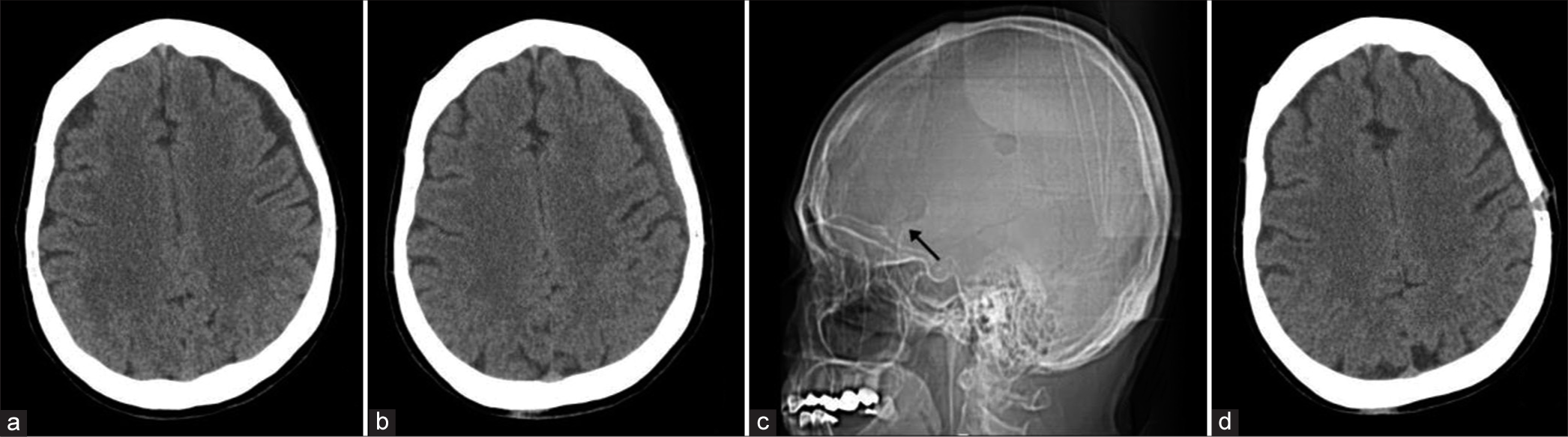

The patient was placed under general anesthesia and had head pin fixation. The localization for the right burr hole at the pterional region was made by means of Stryker navigation, similar to the description for Case 2, as shown in

By the 1st postoperative day, the patient was free of headaches and dizziness. The patient then refused placement in an intermediate care facility. Once home, he experienced several falls, striking his head on the last one. He reported no loss of consciousness during any of the falls.

On examination for the second admission, the patient was awake and oriented times 3. There was a new laceration over the left frontal region, overlying a scalp hematoma. The contra-lateral burr hole incision was healing well.

The head CT scan showed resolution of the right-sided subdural collection but enlarging subacute left subdural hematoma, with evidence of recent rebleeding and increase in the left-to-right midline shift [

The patient underwent a contralateral evacuation of the subdural hematoma by means of a pterional burr hole and coagulation of the left MMA, according to the technique described above.

The postoperative course had no adverse neurological events. Head CT scans on postoperative day 5 showed complete resolution of both subdural collections. On an outpatient follow-up 3 months later, the patient remained asymptomatic, neurologically normal, and caring for himself at home [

Case 4

This was a 67-year-old right-handed woman who presented with increasing headaches after falling down three steps at home earlier that day, with a witnessed head strike. On examination, there was a left scalp laceration; the patient was alert and oriented times 3 and had a non-focal neurological examination. The head CT showed a small left frontal hygroma [

On follow-up 2 months later, the patient continued to have headaches and dizziness, especially on getting up from the lying position. The neurological examination continued to be normal. A follow-up head CT scan demonstrates the conversion of the left-sided hygroma into a CSH, with an increase in volume and signal intensity [

The patient opted for general anesthesia. A left pterional burr hole was placed according to the previously described technique, with the assistance of intraoperative fluoroscopy.[

Headaches and dizziness resolved within the next few days. On 4 4-week postoperative follow-up, the patient had no complaints. CT scan of the head demonstrated complete resolution of the previously existent subdural hematoma [

Case 5

This was a 50-year-old male with multiple previous visits to the emergency room who complained of mild aching headaches following a fall with a head strike the same day while intoxicated. There was no loss of consciousness. The patient had suffered another head injury earlier that week: a hammer blow to the right forehead, again with no impairment of consciousness, but followed by vomiting. The only comorbidity was chronic alcoholism.

On physical examination, there were abrasions to the right forehead and right lateral temporal area. The patient was awake, alert, orientated, and following commands but mildly agitated, with a Glasgow coma scale score of 15. The neurological examination and vital signs were normal.

The CT scan of the head demonstrated an acute on chronic left temporal subdural hematoma, with a midline shift of 4.4 mm, which extended to the tentorium. The subdural hematoma was evacuated by means of a left pterional burr hole and coagulation of the MMA, as described above.

Postoperatively, the patient’s headaches improved, and he remained neurologically stable. Follow-up head CT scan at 3 months demonstrated complete resolution of the subdural collection.

Case 6

This was an 86-year-old woman who presented with altered mental status after being found lying in the bathroom for several hours. On examination, the patient looked generally well and was confused but cooperative. The neurological examination was non-focal.

Comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dementia, and seizures. Her medication included amlodipine, aspirin, atorvastatin, escitalopram oxalate, hydrochlorothiazide, insulin, levetiracetam, losartan, metformin, and Vitamin A. On the day of admission, she experienced a generalized tonic-clonic seizure requiring intubation.

Head CT scans, before and after the seizure, showed a right CSH with layering of signal intensity indicating rebleeding. It also showed effacement of ipsilateral sulci and midline shift.

Due to the wider distribution of the subdural collection over the right hemisphere, as well as the presence of recent bleeding in the posterior parietal portion of the subdural collection, two burr holes were placed. The left pterional burr hole was performed according to the technique described above. The MMA was coagulated, and clear xanthochromic fluid was drained. The other ipsilateral burr hole was placed over the right parietal region, similar to the one described in Case 4. The parietal opening led to a well-formed outer subdural membrane and liquefied xanthochromic subdural fluid followed by dark, fresh blood. The patient was extubated at the completion of the procedure. An early CT scan showed a satisfactory appearance.

The symptoms disappeared after the procedure; the patient was discharged with home care and disappeared to follow-up. She returned a year later with a contralateral stroke. The subdural collection had completely disappeared.

Case 7

This was a 68-year-old male who presented to the emergency department with cognitive impairment, lethargy, and urinary incontinence after sustaining a fall from standing in a parking lot while intoxicated on the same day of admission. Medical history revealed alcoholism, active smoking, imbalance, use of a cane, and urinary incontinence.

On examination, the patient was disoriented to time and place. There was spasticity of all four limbs, pain on mobilization of the left shoulder, and diffuse atrophy of intrinsic muscles of both hands. Motor power was symmetrical in all limbs. There was a left periorbital hematoma with abrasions to the left forehead, bilateral abrasions on both hands and bilateral pitting edema.

The head CT scan showed bilateral chronic subdural collections, much larger on the left and with evidence of recent rebleeding. Imaging also showed spondylotic cervical cord compression, which explained the bilateral spasticity.

The patient first underwent placement of a left pterional burr hole and coagulation of the MMA under local anesthesia, according to the technique described above. Intubation was avoided due to the coexistent compressive cervical myelopathy. A well-formed outer membrane was found, leading to old blood initially followed by fresher fluid bleeding. There was an improvement in the patient’s condition after surgery. However, he continued to be weaker and spastic on the left side, and there was an increase in the size of the contralateral right subdural collection. Therefore, 5 days later, the patient underwent another uneventful pterional burr hole and coagulation of the MMA on the contralateral right side, again under local anesthesia. He recovered well after both procedures. Later on, during this admission, the patient underwent decompressive surgery to the cervical spinal cord.

On 4 week follow-up, there were no longer any neurological deficits. Cognition had improved, but the patient continued to be intermittently disoriented. Sequential head CT scans demonstrated ongoing bilateral improvement with a decrease in the size of both subdural collections. At 7 weeks postoperatively, the patient’s neurological status and cognition were back to normal. The patient was transferred from rehab to home. The CT scan of the head showed minimal residual collections on both sides.

Case 8

This was a 62-year-old man, an active soccer player, who had undergone a previous left mini-craniotomy for evacuation of an acute subdural hematoma 10 weeks previously. At that time, he was hit on the head with a ball while playing soccer. On follow-up, he complained of lethargy and lack of drive. He had been placed on dexamethasone elsewhere. He had quit playing soccer since the initial surgery. There were no comorbidities.

On examination, the patient’s cognition was intact, and the neurological examination was normal. The head CT scan showed findings consistent with residual/recurrent subacute left subdural hematoma.

Under general anesthesia, the patient underwent a left burr-hole placement with coagulation of the MMA, according to the technique described above. The postoperative course was uneventful; the patient was asymptomatic and continued to have a normal neurological examination at 1 week and 4 months, with progressive disappearance of the subdural collection during this time interval.

Case 9

This was a 42-year-old right-handed man with multiple visits to the emergency room for injuries related to alcohol abuse. On this visit, the patient was intoxicated, complaining of pains involving the entire left side of the body following a fall 3 days previously. Medical history included a chronic right subdural hematoma treated conservatively for the past month, a remote left hemiparesis from a right cerebral stroke treated elsewhere, and a substance abuse disorder.

On preoperative examination, the patient was alert and cooperative, with normal cranial nerves and spastic left hemiparesis attributed to the old stroke.

Sequential head CT scans revealed a preexistent (3 weeks earlier) right CSH on the same side as an atrophic brain from a previous large middle cerebral artery infarct [

A right burr hole and MMA coagulation were performed under general anesthesia, according to the above-described technique.

The procedure was well tolerated, and the patient returned home at baseline neurological status. Postoperative imaging at 10 weeks was very satisfactory because, despite ipsilateral cerebral atrophy, there was complete resolution of the subdural collection [

DISCUSSION

The first successful surgical evacuation of CSHs is attributed to Hulke in 1883.[

More recently, large clinical series have shown that embolization of the MMA following surgical evacuation of CSHs reduces subdural re-accumulation.[

The combination of two interventions, namely, burr-hole drainage of the subdural hematoma plus coagulation of the MMA, into a single minimally invasive procedure appears to be feasible and associated with minimal invasiveness (local or general anesthesia), cheaper price, immediate clinical response, and decreased exposure to radiation. In patients where the subdural collection does not extend to the middle meningeal calvarial entry point, there is the option of the placement of a secondary burr hole.

CONCLUSION

The results of this short series suggest that this combined procedure could safely be considered a choice among the multiple surgical options for drainage of CSHs. The combination of drainage of the subdural collection and simultaneous coagulation of the MMA offers the potential advantages of (a) cost saving by avoiding a second open surgical or endovascular procedure, (b) faster reabsorption of the subdural collection and reversal of symptoms, (c) lesser exposure to radiation, (d) shorter follow-ups, and (e) need for less postoperative imagining. Obviously, larger prospective clinical studies will be needed to ascertain the safety, efficacy, and indications of this procedure as part of the armamentarium for the management of CSHs. Pending the confirmation of its efficacy by larger prospective trials, this procedure might be particularly relevant in developing countries, where the option of endovascular embolization of MMA may not be so readily available and cost containment a more relevant consideration.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

Acknowledgement

We are indebted to Mr. Christopher Boyd for his contributions to the illustrations.

References

1. Abouzari M, Rashidi A, Rezaii J, Esfandiari K, Asadollahi M, Aleali H. The role of postoperative patient posture in the recurrence of traumatic chronic subdural hematoma after burr-hole surgery. Neurosurgery. 2007. 61: 794-7

2. Akamatsu Y, Kashimura H, Kojima D, Yoshida J, Chika K, Komoribayashi N. Correlation between low-density hematoma at 1-week post-middle meningeal artery embolization and rapid resolution of chronic subdural hematoma. World Neurosurg. 2024. 181: e1088-92

3. Bonasia S, Smajda S, Ciccio G, Robert T. Middle meningeal artery: Anatomy and variations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020. 41: 1777-85

4. Cardoso ER. Single pterional burr hole coupled with coagulation of the middle meningeal artery for management of a chronic subdural hematoma in a 98-year-old patient: Illustrative case. Am J Case Rep. 2023. 24: e940045

5. Di Cristofori A, Remida P, Patassini M, Piergallini L, Buonanno R, Bruno R. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematomas. A systematic review of the literature focused on indications, technical aspects, and future possible perspectives. Surg Neurol Int. 2022. 13: 94

6. Drake M, Ullberg T, Nittby H, Marklund N, Wassélius J. Swedish trial on embolization of middle meningeal artery versus surgical evacuation in chronic subdural hematoma (SWEMMA)-a national 12-month multi-center randomized controlled superiority trial with parallel group assignment, open treatment allocation and blinded clinical outcome assessment. Trials. 2022. 23: 926

7. Ducruet AF, Grobelny BT, Zacharia BE, Hickman ZL, DeRosa PL, Andersen KN. The surgical management of chronic subdural hematoma. Neurosurg Rev. 2012. 35: 155-69

8. Haldrup M, Munyemana P, Ma’aya A, Jensen TS, Fugleholm K. Surgical occlusion of middle meningeal artery in treatment of chronic subdural haematoma: Anatomical and technical considerations. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2021. 163: 1075-81

9. Hulke JW. Severe blow on the right temple, followed by right hemiplegia and coma, and then by spastic rigidity of the left arm; trephinning; evacuation of inflammatory fluid by incision through dura matter; quick disappearance if cerebral symptoms; complete recovery. Lancet. 1883. 122: 814-5

10. Ironside N, Nguyen C, Do Q, Ugiliweneza B, Chen CJ, Sieg EP. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. 2021. 13: 951-7

11. Ishihara H, Ishihara S, Kohyama S, Yamane F, Ogawa M, Sato A. Experience in endovascular treatment of recurrent chronic subdural hematoma. Interv Neuroradiol. 2007. 13: 141-4

12. Ivamoto HS, Lemos HP, Atallah AN. Surgical treatments for chronic subdural hematomas: A comprehensive systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2016. 86: 399-418

13. Kan P, Maragkos GA, Srivatsan A, Srinivasan V, Johnson J, Burkhardt JK. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma: A multi-center experience of 154 consecutive embolizations. Neurosurgery. 2021. 88: 268-77

14. Lee KS. How to treat chronic subdural hematoma? Past and now. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2019. 62: 144-52

15. Mandai S, Sakurai M, Matsumoto Y. Middle meningeal artery embolization for refractory chronic subdural hematoma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2000. 93: 686-8

16. Martins C, Yasuda A, Campero A, Ulm AJ, Tanriover N, Rhoton A. Microsurgical anatomy of the dural arteries. Neurosurgery. 2005. 56: 211-51

17. Mehta V, Harward SC, Sankey EW, Nayar G, Codd PJ. Evidence based diagnosis and management of chronic subdural hematoma: A review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2018. 50: 7-15

18. Merland JJ, Théron J, Lasjaunias P, Moret J. Meningeal blood supply of the convexity. J Neuroradiol. 1977. 4: 129-74

19. Sattari SA, Yang W, Shahbandi A, Feghali J, Lee RP, Xu R. Middle meningeal artery embolization versus conventional management for patients with chronic subdural hematoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2023. 92: 1142-54

20. Scerrati A, Visani J, Ricciardi L, Dones F, Rustemi O, Cavallo MA. To drill or not to drill, that is the question: Nonsurgical treatment of chronic subdural hematoma in the elderly. A systematic review. Neurosurg Focus. 2020. 49: E7

21. Solou M, Ydreos I, Gavra M, Papadopoulos EK, Banos S, Boviatsis EJ. Controversies in the surgical treatment of chronic subdural hematoma: A systematic scoping review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022. 12: 2060

22. Takahashi K, Muraoka K, Sugiura T, Maeda Y, Mandai S, Gohda Y. Middle meningeal artery embolization for refractory chronic subdural hematoma: 3 case reports. No Shinkei Geka. 2002. 30: 535-9

23. Tempaku A, Yamauchi S, Ikeda H, Tsubota N, Furukawa H, Maeda D. Usefulness of interventional embolization of the middle meningeal artery for recurrent chronic subdural hematoma: Five cases and a review of the literature. Interv Neuroradiol. 2015. 21: 366-71

24. Uno M. Chronic subdural hematoma-evolution of etiology and surgical treatment. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2023. 63: 1-8

25. Weigel R, Krauss JK, Schmiedek P. Concepts of neurosurgical management of chronic subdural haematoma: Historical perspectives. Br J Neurosurg. 2004. 18: 8-18