- Department of Osteopathic Medicine, Michigan State University, East Lansing,

- Department of Neurological Surgery, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan, United States.

- Department of Pathology, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Rizwan A. Tahir

Department of Neurological Surgery, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_282_2020

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Amanda E. Sion1, Rizwan A. Tahir2, Abir Mukherjee3, Jack P. Rock2. Cranial angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma: A case report and review of literature. 18-Sep-2020;11:295

How to cite this URL: Amanda E. Sion1, Rizwan A. Tahir2, Abir Mukherjee3, Jack P. Rock2. Cranial angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma: A case report and review of literature. 18-Sep-2020;11:295. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10267/

Abstract

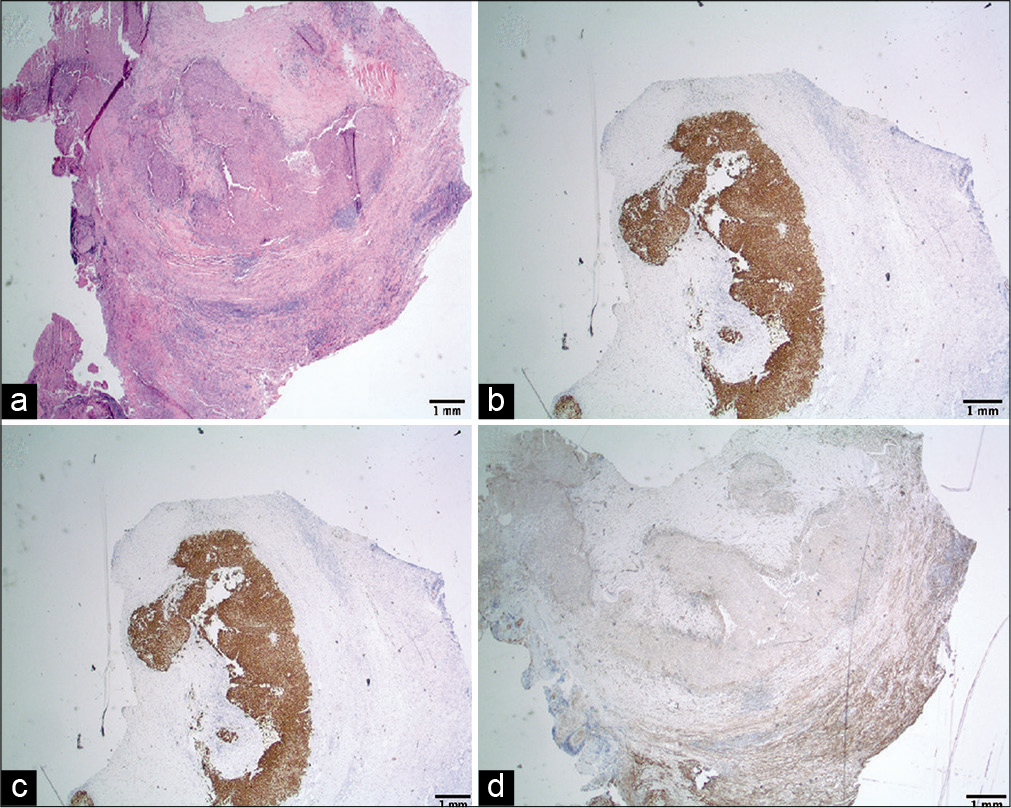

Background: Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma (AFH) is a rare low-grade soft-tissue tumor that typically arises from the deep dermal and subcutaneous tissue of the extremities in children and young adults. Intracranial AFH is exceedingly rare, and only four cases of primary AFH tumors have been reported to date.

Case Description: A 43-year-old male presented to our hospital with headaches, vision changes, and a known brain tumor suspected to be an atypical meningioma. After undergoing craniotomy for resection of the mass, the immunomorphologic features of the resected tumor showed typical features of AFH with ESWR1 (exon7) – ATF1 (exon 5) fusion.

Conclusion: AFH is a difficult tumor to diagnose with imaging and histologic studies. Thus, further knowledge is necessary – particularly of intracranial cases – to aid clinicians in its diagnosis and management.

Keywords: Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, Craniotomy, Meningioma, Neuro-oncology

INTRODUCTION

Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma (AFH) is a rare, slow-growing, and low-grade soft-tissue tumor that typically arises from deep dermal and subcutaneous tissue of the extremities in children and young adults. The majority of these tumors present in the first three decades of life and account for 0.3% of all soft-tissue tumors. Intracranial AFH is rare, and currently, there are only four reports of primary intracranial AFH in the literature [

CASE DESCRIPTION

Patient case

A 43-year-old right-handed male with no significant medical history presented to our facility complaining of intermittent left-sided headaches associated with blurry vision in the right eye and episodes of transient word finding difficulty for 1 year. The patient stated that he had lived in Saudi Arabia, where he was seen by a neurosurgeon who ordered a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain which, as per the clinicians notes, showed an “atypical meningioma;” however, no images or official reports were available. The patient was started on levetiracetam 500 mg BID. He continued having headaches with no further episodes of blurry vision. Consequently, the patient presented to our emergency department for a second opinion. On physical examination, the patient was neurologically intact with no deficits. Computed tomography (CT) of the brain showed multiple ring-shaped lesions with significant perilesional vasogenic edema suspicious for abscesses or necrotic masses. The patient endorsed a 20 lb weight loss due to decreased appetite over the past year. Blood work revealed hemoglobin (Hb) of 10.8 g/dL as well as an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and prothrombin time.

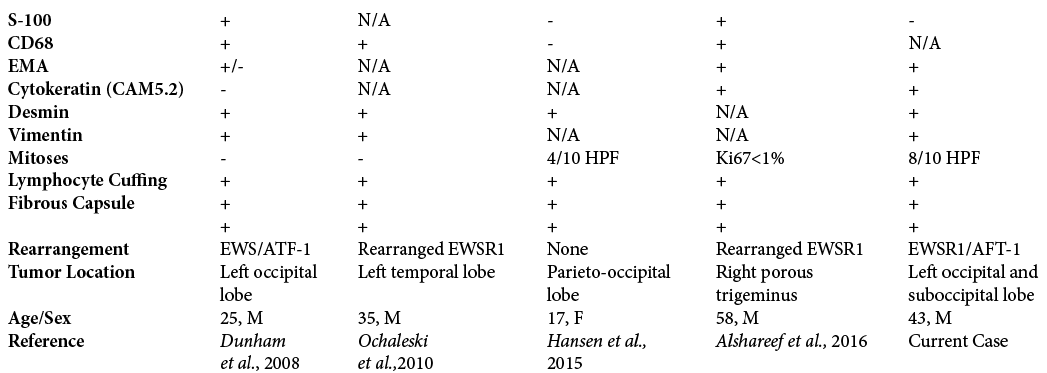

The patient was admitted, and MRI of the brain showed an isointense T1 and hyper-intense T2 avidly enhancing extra-axial mass near the posterior edge of the tentorium cerebelli on the left side extending superiorly and inferiorly to the tentorium [

Figure 1:

(a-d) Cranial angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma. (a) T1 axial head magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Homogeneously hypointense infratentorial 25.0 mm lesion; (b) T2 postcontrast MRI of the brain. Multilobulated enhancing mass at the lateral aspect of the tentorium on the left; (c) T1 coronal MRI of the brain. Homogenous lesion extending above and below the tentorium, possible occlusion of the transverse sinus as it is not visualized; (d) Axial FLAIR MRI of the brain.

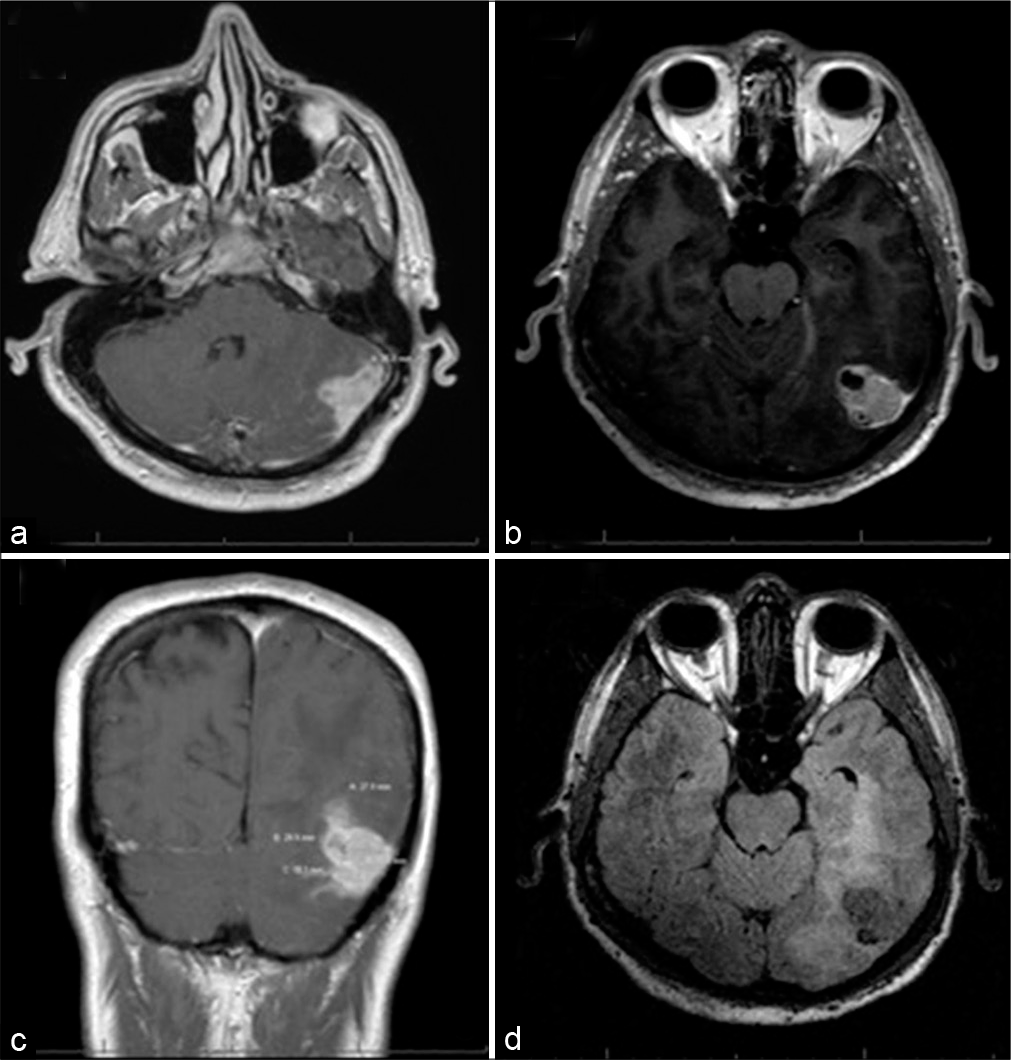

One month later, the patient underwent a left occipital and suboccipital craniotomy for resection of the mass. Using the navigation, two separate craniotomies were made, one above the transverse sinus and one below. The supratentorial opening demonstrated an obvious tumor that was adherent to the sinus. Although preoperative imaging suggested sinus occlusion, care was taken to not violate or injure the sinus due to preserved turgor suggesting continued flow. The supratentorial portion was 95% debulked with a small amount of residual abnormal tissue not resected due to firm adherence to the surrounding parenchyma and a large neighboring vein. The second craniotomy was opened infratentorially, and the tumor was resected between the supra and infratentorial compartments along the transverse sinus. Postoperatively, the patient remained intact with improvement in his headaches and blurry vision at 6-week follow-up with MRI demonstrating significant debulking with a small possible residual tumor in operative bed. A multidisciplinary tumor board recommendation was for repeat MRI in 6 months [

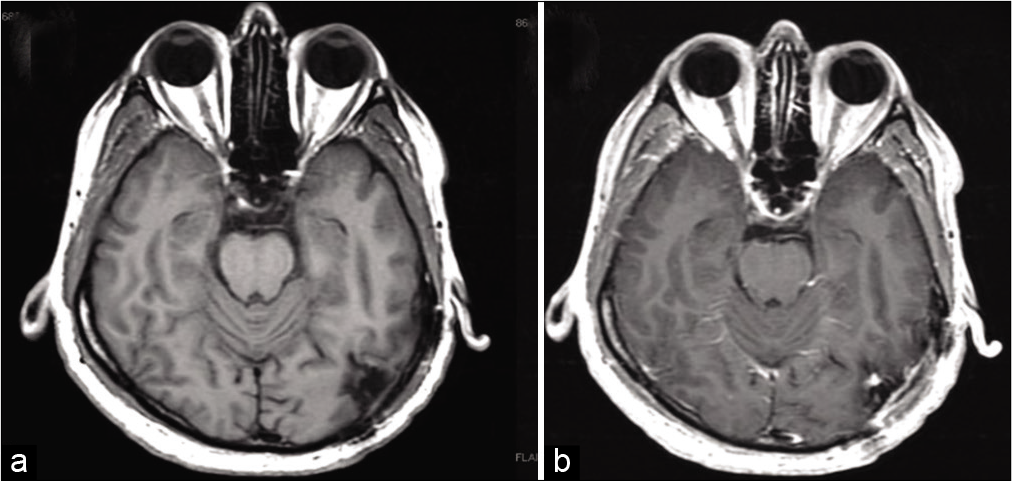

Microscopic examination revealed a dural-based multinodular tumor with a fibrous capsule [

Figure 3:

(a-d) Microscopic analysis of tumor specimen. (a) Pale histiocytoid tumor cells (lower half) with peripheral inflammatory response and hemosiderin deposition (hematoxylin and eosin), (b) and (c) the neoplastic cells are strongly and diffusely immunoreactive to desmin and Cam 5.2 (Immunoperoxidase ), and (d) the neoplastic cells are negative for somatostatin receptor 2A.

DISCUSSION

The first AFH diagnosis was made in 1979 by Enzinger; however, due to a growing number of reports, AFH is now characterized by the World Health Organization as a slow-growing tumor of uncertain differentiation with intermediate metastatic potential. These tumors range from 2 to 4 cm, but growth up to 10 cm has been reported.[

Genetically, AFH is associated with three characteristic translocations: EWSR1-CREB1, EWSR1-ATF1, and FUSATF1.[

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are useful in the diagnosis of AFH because they can detect characteristics that other methods miss. Thway et al. suggested that RT-PCR should be a first-line diagnostic tool due to its specificity for AFH and to use FISH as the second line to detect EWSR1 rearrangements in RT-PCR-negative cases that fit the criteria for AFH.[

Intracranial AFH patients have reported symptoms of migraines, fatigue, vision changes, and seizures before the definitive diagnosis was made. In a report by Hansen et al., a 17-year-old female patient suffered from migraines with auras and fatigue for 3 years until a change in her headaches prompted hospital referral and a subsequent MRI. The diagnosis of anemia and intracranial AFH was made, and after removal of the tumor, her headaches and anemia subsided.[

AFH patients often present with signs of uncontrolled IL-6 production, such as pyrexia, malaise, weight loss, anemia, elevated CRP, and night sweats.[

Years after searching for the source of uncontrolled IL-6 production, it was discovered that what appeared to be a simple Baker’s cyst in the knee was an AFH. The tocilizumab was stopped and after the tumor was removed, the patient’s IL-6 related symptoms subsided.[

Our patient presented with headaches, vision changes, a 20-lb weight loss over 1 year, as well as anemia (Hb 10.8 g/dL), an elevated CRP of 5.7 (ref < 0.5 mg/dL), and an elevated ESR of 60 mm/h (ref < 15mm/h). One study suggests that these abnormal laboratory values are related to cytokine production by the tumor and parallel the disease course. This group studied a 17-year-old female with an upper extremity AFH who presented with, among other abnormal laboratory values, anemia, and an elevated CRP.[

Our tumor had most of the typical histopathologic features described in AFH, including multinodularity, fibrous capsule, peripheral inflammatory response, and hemosiderin deposition. Angiomatoid spaces or myxoid areas were absent. The immunoprofile was also typical except for the strong and diffuse immunoreactivity to cytokeratins. Although metastasis of AFH is rare, Costa et al. describe features of the tumor that may predict spread and recurrence. Irregular tumor borders, as well as tumors located on the head and neck, were associated with higher local recurrence rates, and the depth of the tumor was associated with a higher rate of subsequent metastasis.[

As more cases are being reported in a variety of anatomical sites, the comparison can be made between tumors originating from somatic tissue and those originating outside somatic tissue. Chen et al. compared AFH tumors arising from various locations and found that the most significant differences between somatic and extrasomatic tumor origins are the age of the patients and the clinical outcomes.[

AFH is difficult to diagnose for several reasons. Nodules of ovoid to spindle cells with blood-filled pseudoangiomatoid spaces and surrounding lymphoid cuff also present in other tumors. In addition, there is histological overlap with other lesions, lack of a specific immunophenotype, and increased occurrences in unusual extrasomatic sites.[

CONCLUSION

AFH is a difficult tumor to diagnose with imaging and histologic studies. Thus further knowledge is necessary -particularly of intracranial cases - to aid clinicians in its diagnosis and management.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Agaimy A. Paraneoplastic disorders associated with miscellaneous neoplasms with focus on selected soft tissue and undifferentiated/rhabdoid malignancies. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019. 36: 269-78

2. Akiyama M, Yamaoka M, Mikami-Terao Y, Yokoi K, Inoue T, Hiramatsu T. Paraneoplastic syndrome of angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma may be caused by EWSR1-CREB1 fusion-induced excessive interleukin-6 production. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015. 37: 554-9

3. Alshareef MA, Almadidy Z, Baker T, Perry A, Welsh CT, Vandergrift WA. Intracranial angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma: Case report and literature review. World Neurosurg. 2016. 96: 403-9

4. Ballester LY, Meis JM, Lazar AJ, Prabhu SS, Hoang KB, Leeds NE. Intracranial myxoid mesenchymal tumor with EWSR1-ATF1 fusion. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2020. 79: 347-51

5. Chen G, Folpe AL, Colby TV, Sittampalam K, Patey M, Chen MG. Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma: Unusual sites and unusual morphology. Mod Pathol. 2011. 24: 1560-70

6. Costa MJ, Weiss SW. Angiomatoid malignant fibrous histiocytoma: A follow-up study of 108 cases with evaluation of possible histologic predictors of outcome. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990. 14: 1126-32

7. Dunham C, Hussong J, Seiff M, Pfeifer J, Perry A. Primary intracerebral angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma: Report of a case with a t(12;22)(q13;q12) causing Type 1 fusion of the EWS and ATF-1 genes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008. 32: 478-84

8. Enzinger FM. Angiomatoid malignant fibrous histiocytoma: A distinct fibrohistiocytic tumor of children and young adults simulating a vascular neoplasm. Cancer. 1979. 44: 2147-57

9. Ghanbari N, Lam A, Wycoco V, Lee G. Intracranial myxoid variant of angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma: A case report and literature review. Cureus. 2019. 11: e4261

10. Hansen JM, Larsen VA, Scheie D, Perry A, Skjøth-Rasmussen J. Primary intracranial angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma presenting with anaemia and migraine-like headaches and aura as early clinical features. Cephalalgia. 2015. 35: 1334-6

11. Ochalski PG, Edinger JT, Horowitz MB, Stetler WR, Murdoch GH, Kassam AB. Intracranial angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma presenting as recurrent multifocal intraparenchymal hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2010. 112: 978-82

12. Rossi S, Szuhai K, Ijszenga M, Tanke HJ, Zanatta L, Sciot R. EWSR1-CREB1 and EWSR1-ATF1 fusion genes in angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007. 13: 7322-8

13. Saito K, Kobayashi E, Yoshida A, Araki Y, Kubota D, Tanzawa Y. Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma: A series of seven cases including genetically confirmed aggressive cases and a literature review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2017. 18: 31

14. Thway K, Gonzalez D, Wren D, Dainton M, Swansbury J, Fisher C. Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma: Comparison of fluorescence in situ hybridization and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction as adjunct diagnostic modalities. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015. 19: 137-42

15. Villiger PM, Cottier S, Jonczy M, Koelzer VH, RouxLombard P, Adler S. A simple Baker’s cyst? Tocilizumab remits paraneoplastic signs and controls growth of IL-6-producing angiomatoid malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014. 53: 1350-2

16. Waters BL, Panagopoulos I, Allen EF. Genetic characterization of angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma identifies fusion of the FUS and ATF-1 genes induced by a chromosomal translocation involving bands 12q13 and 16p11. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000. 121: 109-16