- Department of Neurosurgery, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

Correspondence Address:

Ha Son Nguyen

Department of Neurosurgery, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.191076

Copyright: © 2016 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Sharma A, Nguyen HS, Sharma A, Lozen A, Kurpad S. Delayed hydrocephalus associated with traumatic atlanto-occipital dislocation: Case report and literature review. Surg Neurol Int 22-Sep-2016;7:

How to cite this URL: Sharma A, Nguyen HS, Sharma A, Lozen A, Kurpad S. Delayed hydrocephalus associated with traumatic atlanto-occipital dislocation: Case report and literature review. Surg Neurol Int 22-Sep-2016;7:. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/delayed-hydrocephalus-associated-traumatic-atlanto%e2%80%91occipital-dislocation-case-report-literature-review/

Abstract

Background:Traumatic atlanto-occipital dislocation (AOD) is a rare but often fatal injury. Consequently, long-term data regarding surviving patients have been limited. In particular, the occurrence of hydrocephalus is not well-documented.

Case Description:A 33-year-old male sustained AOD as a consequence of a motor vehicle collision. Although he did well initially after an occipitocervical fusion, 1 month after his operation, he exhibited signs of increased intracranial pressure (bilateral abducens nerve palsies, worsening headaches, and fatigue). He was found to have hydrocephalus, which was responsive to shunting.

Conclusion:Manifestations of hydrocephalus after AOD can be variable, ranging from interval ventricular dilatation to pseudomeningoceles and syringomyelia. In addition, the timing of presentation can be acute, requiring emergent external ventricular drainage, or delayed, requiring ongoing vigilance. Consequently, as more patients survive this once thought to be fatal injury, caution for hydrocephalus is stressed.

Keywords: Atlanto-occipital dislocation, hydrocephalus, occipitocervical fusion

BACKGROUND

Traumatic atlanto-occipital dislocation (AOD) is a rare but often fatal injury. Consequently, long-term data regarding surviving patients have been limited. In particular, the occurrence of hydrocephalus is not well-documented. We report a patient with delayed hydrocephalus and review the literature.

CASE PRESENTATION

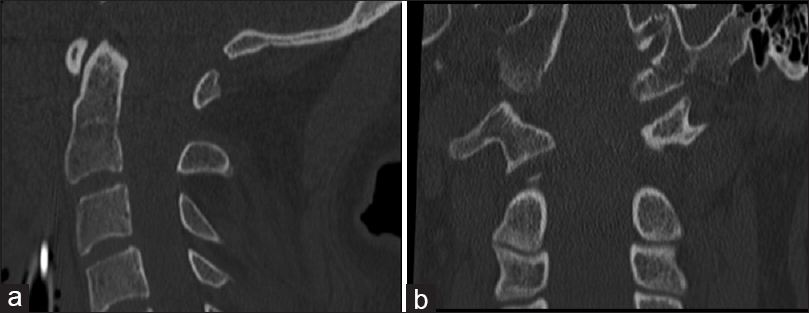

A 33-year-old male presented after a high-velocity motor vehicle collision. On presentation, his Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 3T, with reactive pupils but no corneal/cough/gag reflexes. Imaging demonstrated AOD [

DISCUSSION

AOD involves significant instability of the craniocervical junction. The tectorial membrane and alar ligaments are the most commonly injured ligaments. Most frequent mechanisms of injury are motor vehicle accidents and pedestrian vehicle accidents. Patients often die in the field; autopsy studies have noted that AOD was present in 6–20% of the patients who sustained fatal traffic accidents.[

Neurological presentation can be variable, ranging from no deficits to severe deficits (from injuries to cranial nerves, brain stem, and spinal cord), ventilator dependence, and death.[

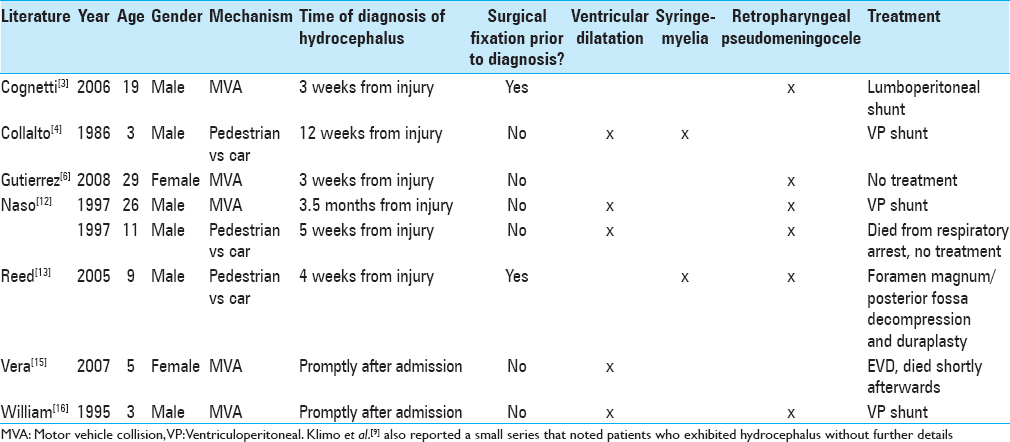

Manifestations of hydrocephalus after AOD include pseudomeningocele, syringomyelia, and interval ventricular dilatation.

Though some series report a high rate of hydrocephalus (up to 30%) associated with AOD,[

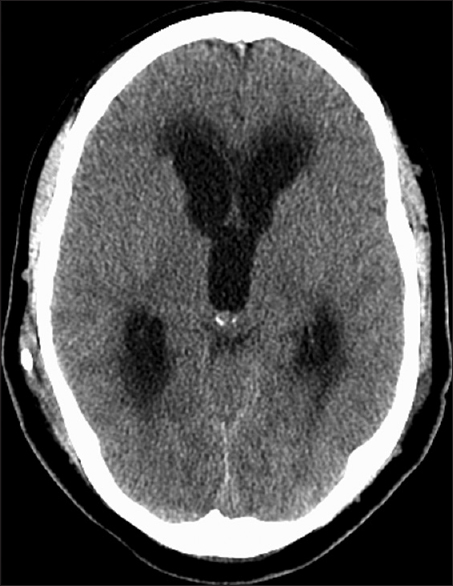

Our patient exhibited bilateral abducens nerve palsies associated with ventricular dilatation. This presentation is consistent with a delayed hydrocephalus. Though injury to the abducens nerve is commonly associated with AOD, the time delay to this symptom argues against its association with AOD. Our patient also had scattered IVH and SAH, requiring a temporary EVD. This likely increased his risk for delayed hydrocephalus.

CONCLUSION

Manifestations of hydrocephalus after AOD can be variable, ranging from interval ventricular dilatation to pseudomeningoceles and syringomyelia. In addition, the timing of presentation can be acute, requiring emergent EVD, or delayed, requiring ongoing vigilance. Consequently, as more patients survive this once thought to be fatal injury, caution for hydrocephalus is stressed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Astur N, Sawyer JR, Klimo P, Kelly DM, Muhlbauer M, Warner WC. Traumatic atlanto-occipital dislocation in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014. 22: 274-82

2. Bucholz RW, Burkhead WZ. The pathological anatomy of fatal atlanto-occipital dislocations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979. 61: 248-50

3. Cognetti DM, Enochs WS, Willcox TO. Retropharyngeal pseudomeningocele presenting as dysphagia after atlantooccipital dislocation. Laryngoscope. 2006. 116: 1697-9

4. Collalto PM, DeMuth WW, Schwentker EP, Boal DK. Traumatic atlanto-occipital dislocation. Case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986. 68: 1106-9

5. Davis D, Bohlman H, Walker AE, Fisher R, Robinson R. The pathological findings in fatal craniospinal injuries. J Neurosurg. 1971. 34: 603-13

6. Gutierrez-Gonzalez R, Boto GR, Perez-Zamarron A, Rivero-Garvia M. Retropharyngeal pseudomeningocele formation as a traumatic atlanto-occipital dislocation complication: Case report and review. Eur Spine J. 2008. 17: S253-6

7. Hida K, Iwasaki Y, Imamura H, Abe H. Posttraumatic syringomyelia: Its characteristic magnetic resonance imaging findings and surgical management. Neurosurgery. 1994. 35: 886-91

8. Hosalkar HS, Cain EL, Horn D, Chin KR, Dormans JP, Drummond DS. Traumatic atlanto-occipital dislocation in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005. 87: 2480-8

9. Klimo P, Astur N, Gabrick K, Warner WC, Muhlbauer MS. Occipitocervical fusion using a contoured rod and wire construct in children: A reappraisal of a vintage technique. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013. 11: 160-9

10. Labbe JL, Leclair O, Duparc B. Traumatic atlanto-occipital dislocation with survival in children. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2001. 10: 319-27

11. Mendenhall SK, Sivaganesan A, Mistry A, Sivasubramaniam P, McGirt MJ, Devin CJ. Traumatic atlantooccipital dislocation: Comprehensive assessment of mortality, neurologic improvement, and patient-reported outcomes at a Level 1 trauma center over 15 years. Spine J. 2015. 15: 2385-95

12. Naso WB, Cure J, Cuddy BG. Retropharyngeal pseudomeningocele after atlanto-occipital dislocation: Report of two cases. Neurosurgery. 1997. 40: 1288-90

13. Reed CM, Campbell SE, Beall DP, Bui JS, Stefko RM. Atlanto-occipital dislocation with traumatic pseudomeningocele formation and post-traumatic syringomyelia. Spine. 2005. 30: E128-33

14. Shamoun JM, Riddick L, Powell RW. Atlanto-occipital subluxation/dislocation: A “survivable” injury in children. Am Surg. 1999. 65: 317-20

15. Vera M, Navarro R, Esteban E, Costa JM. Association of atlanto-occipital dislocation and retroclival haematoma in a child. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007. 23: 913-6

16. Williams MJ, Elliott JL, Nichols J. Atlantooccipital dislocation: A case report. J Clin Anesth. 1995. 7: 156-9

Fred Cohen

Posted October 4, 2016, 1:01 pm

In my experience, hydrocephalus is a frequent accompaniment of allanto-occipital dislocations and its delayed occurrence should be anticipated. This is equally true for adults and children. When the initial treatment is a halo and vest, shunt surgery can be difficult but achievable.