- Department of Neurosurgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, Texas, USA

Correspondence Address:

Sandi Lam

Department of Neurosurgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, Texas, USA

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.172532

Copyright: © 2015 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Lam S, Wagner KM, Middlebrook E, Luerssen TG. Delayed intracranial hypertension after surgery for nonsyndromic craniosynostosis. Surg Neurol Int 23-Dec-2015;6:187

How to cite this URL: Lam S, Wagner KM, Middlebrook E, Luerssen TG. Delayed intracranial hypertension after surgery for nonsyndromic craniosynostosis. Surg Neurol Int 23-Dec-2015;6:187. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/delayed-intracranial-hypertension-after-surgery-for-nonsyndromic-craniosynostosis/

Abstract

Keywords: Cranial synostosis, cranial vault, craniofacial, craniosynostosis, intracranial hypertension, intracranial pressure

CASE EXAMPLE

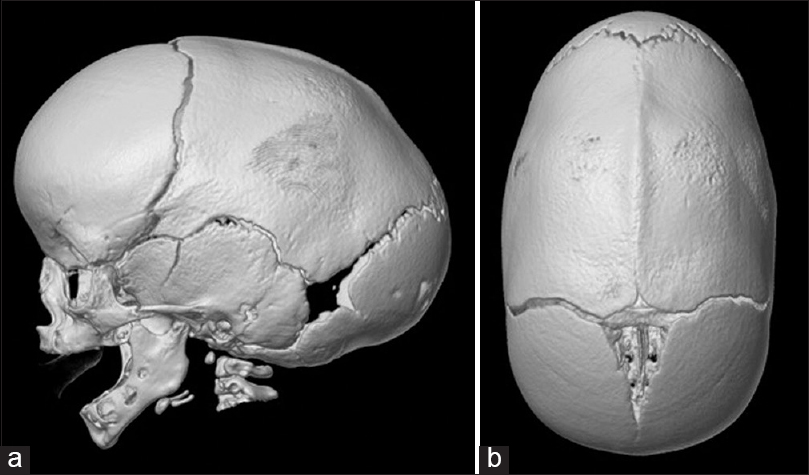

A 2-month-old boy presented with an elongated (anterior-posterior) head shape, prominent wide forehead, and bitemporal narrowing. There was a visible and palpable bony keel along the sagittal suture that was present since birth [

SUMMARY OF POSTOPERATIVE INTRACRANIAL HYPERTENSION AFTER SURGERY ON NONSYNDROMIC CRANIOSYNOSTOSIS

Single-suture synostosis is reported to be associated with elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) in up to 15–20% of cases.[

RETROSPECTIVE CASE SERIES

Cetas et al. reported that 6.2% of patients who underwent remodeling surgery for single-suture synostosis, and who were followed for at least 3 years, had postoperative elevated ICP. They followed 81 patients from a total of 156 consecutive patients, with average age at operation of 9.1 months.[

Adamo and Pollack reviewed 164 patients who underwent surgery for nonsyndromic sagittal suture synostosis. One hundred forty three patients had at least 2 years’ follow-up and were followed up for an average of 43.8 months. A total of 1.5% of these patients had to undergo a second surgery for growth restriction leading to an elevation of ICP:[

Thomas et al. reported on 217 children with nonsyndromic sagittal synostosis followed for a mean of 86 months. The overall rate of raised ICP following sagittal synostosis surgery was 6.9%, found at an average of 51 months after initial surgery. Two types of surgery had different outcomes at this British institution: 1.6% (2 out of 128 patients) who underwent calvarial remodeling versus 14.6% (13 out of 89 patients) who underwent modified sagittal strip craniectomy developed raised ICP.[

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

In a systematic review, Christian et al. found that 5% of patients with sagittal synostosis and 4% of patients with any nonsyndromic craniosynostosis (single- or multiple-suture involvement) developed IH postoperatively.[

MECHANISMS AND RISK FACTORS

A possible mechanism for elevated ICP in children who have undergone suturectomy is stenosis of other sutures.[

Possible risk factors for the development of elevated ICP after surgery gleaned from various case series include male sex, sagittal suture synostosis, and progressive synostosis of sutures that was not present at birth.[

Another cause may be progression of the underlying pathology that led to synostosis. There are a variety of genetic variations that have been implicated in syndromic synostosis: TWIST1 is a transcription factor involved in mesodermal patterning, transforming growth factor beta is involved in cranial suture fusion, and bone morphogenic protein may be part of a signaling cascade involved in restenosis.[

IN PRACTICE

At Texas Children's Hospital, we have a dedicated multidisciplinary craniosynostosis surgery program, where care is integrated for patients and families. Multidisciplinary care includes neurosurgery, plastic surgery, social work, neuropsychology, developmental pediatrics, otolaryngology, and ophthalmology involvement. We follow patients postoperatively on an annual basis until they reach their teenage years. Cetas et al. have recommended screening until the child is at least 6 years old.[

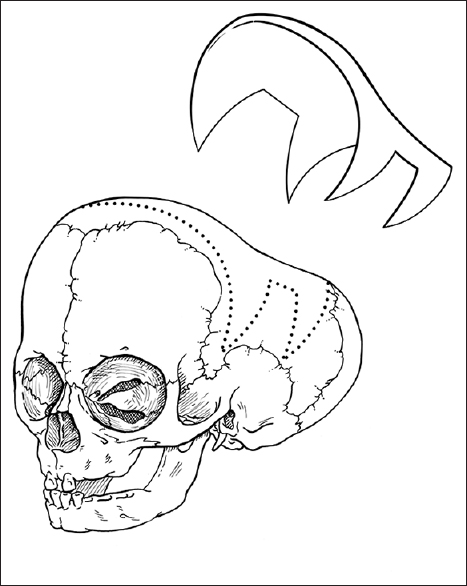

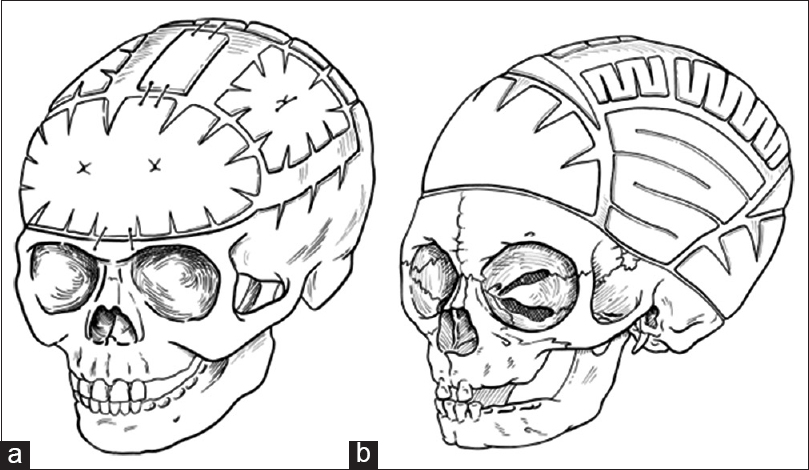

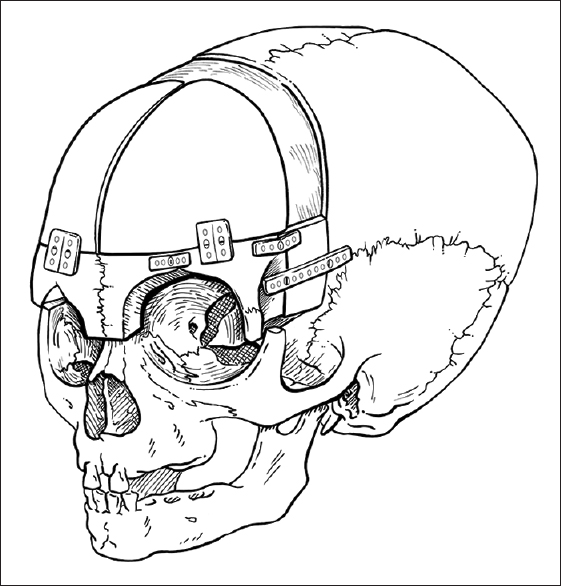

For the child in the above case example, we typically offer endoscopic sagittal synostectomy with bilateral wedge-shaped craniectomies and barrel-stave cuts at 2 months of age requiring overnight observation after surgery, followed by postoperative helmeting. Serial follow-up has shown excellent results at our center, though we remain vigilant in long-term follow-up. Children presenting with sagittal synostosis after 3 months of age are typically offered open surgical correction with modified pi technique or other calvarial vault remodeling techniques tailored to age at surgery.

While the cases of restenosis in the literature tend to be male patients who had surgery at or younger than 5 months of age, Patel et al. found that children who undergo corrective surgery for sagittal synostosis prior to 6 months of age have better long-term neuropsychological outcomes than children who have surgery after 6 months of age.[

Resource-limited environments may present additional challenges. Surgeons may not have access to nor training for minimally invasive techniques; postoperative helmeting also requires additional expenditure. Open reconstructive surgery is typically the most viable option in certain settings. Experienced surgical teams working with limited resources need careful patient selection, surgical planning, and efficient technical execution to minimize morbidity and optimize outcomes. There is ongoing exploration in determining the most appropriate treatment.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Adamo MA, Pollack IF. A single-center experience with symptomatic postoperative calvarial growth restriction after extended strip craniectomy for sagittal craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2010. 5: 131-5

2. Bristol RE, Lekovic GP, Rekate HL. The effects of craniosynostosis on the brain with respect to intracranial pressure. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2004. 11: 262-7

3. Cetas JS, Nasseri M, Saedi T, Kuang AA, Selden NR. Delayed intracranial hypertension after cranial vault remodeling for nonsyndromic single-suture synostosis. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013. 11: 661-6

4. Christian EA, Imahiyerobo TA, Nallapa S, Urata M, McComb JG, Krieger MD. Intracranial hypertension after surgical correction for craniosynostosis: A systematic review. Neurosurg Focus. 2015. 38: E6-

5. Patel A, Yang JF, Hashim PW, Travieso R, Terner J, Mayes LC. The impact of age at surgery on long-term neuropsychological outcomes in sagittal craniosynostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014. 134: 608e-17e

6. Sood S, Marupudi N, Haridas A, Ham SD. Letter to the editor: Intracranial pressure and sagittal craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015. 16: 351-5

7. Souweidane MM. Periodical shifts in the surgical correction of sagittal craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015. 15: 347-8

8. Tamburrini G, Caldarelli M, Massimi L, Santini P, Di Rocco C. Intracranial pressure monitoring in children with single suture and complex craniosynostosis: A review. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005. 21: 913-21

9. Thomas GP, Johnson D, Byren JC, Judge AD, Jayamohan J, Magdum SA. The incidence of raised intracranial pressure in nonsyndromic sagittal craniosynostosis following primary surgery. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015. 15: 350-60

10. Thomas GP, Johnson D, Byren JC, Judge AD, Jayamohan J, Magdum SA. Periodical shifts in the surgical correction of sagittal craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015. 15: 348-9

11. Yarbrough CK, Smyth MD, Holekamp TF, Ranalli NJ, Huang AH, Patel KB. Delayed synostoses of uninvolved sutures after surgical treatment of nonsyndromic craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2014. 25: 119-23