- Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital de Especialidades, Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, México City, Mexico,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital de Especialidades No. 71, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Torreón, Coahuila, Mexico,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Kantonsspital St.Gallen, St.Gallen, Switzerland,

- Department of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Hospital de Pediatría, Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, México City, México,

- President of the Mexican Society of Neurological Surgery, Mexico City, México; Latin American Federation of Neurosurgical Societies, Montevideo, Uruguay; Spine Clinic, The American British Cowdray Medical Center IAP, Mexico City, Mexico; World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies, Nyon, Vaud, Switzerland,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital 1° de Octubre, ISSSTE, Mexico,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Instituto Nacional de Neurología y Neurocirugía “Manuel Velasco Suárez”, Mexico,

- Laboratory of Comparative Cognition, Faculty of Psychology, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico,

- Graduate School of Neural and Behavioural Sciences, International Max Planck Research School, Tuebingen University, Tuebingen, Germany.

Correspondence Address:

Bayron A. Sandoval- Bonilla M.D. M.Sc, CMN Hospital de Especialidades, Department of Neurosurgery, Mexico City, Mexico.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_813_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: B. A. Sandoval-Bonilla1, María F. De la Cerda-Vargas2, Martin N. Stienen3, Bárbara Nettel-Rueda1, Alma G. Ramírez-Reyes4, José A. Soriano-Sánchez5, Carlos Castillo-Rangel6, Sonia Mejia-Pérez7, V. R. Chávez-Herrera1, Pedro Navarro-Domínguez2, J. J. Sánchez-Dueñas8, Araceli Ramirez-Cardenas9. Discrimination of residents during neurosurgical training in Mexico: Results of a survey prior to SARS-CoV-2. 20-Dec-2021;12:618

How to cite this URL: B. A. Sandoval-Bonilla1, María F. De la Cerda-Vargas2, Martin N. Stienen3, Bárbara Nettel-Rueda1, Alma G. Ramírez-Reyes4, José A. Soriano-Sánchez5, Carlos Castillo-Rangel6, Sonia Mejia-Pérez7, V. R. Chávez-Herrera1, Pedro Navarro-Domínguez2, J. J. Sánchez-Dueñas8, Araceli Ramirez-Cardenas9. Discrimination of residents during neurosurgical training in Mexico: Results of a survey prior to SARS-CoV-2. 20-Dec-2021;12:618. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=11299

Abstract

Background: Recent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic represents an important negative impact on global training of neurosurgery residents. Even before the pandemic, discrimination is a challenge that neurosurgical residents have consistently faced. In the present study, we evaluated discriminatory conditions experienced by residents during their neurosurgical training in Mexico before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Methods: An electronic survey of 18 questions was sent among residents registered in the Mexican Society of Neurological Surgery (MSNS), between October 2019 and July 2020. Statistical analysis was made in IBM SPSS Statistics 25. The survey focused on demographic characteristics, discrimination, personal satisfaction, and expectations of residents.

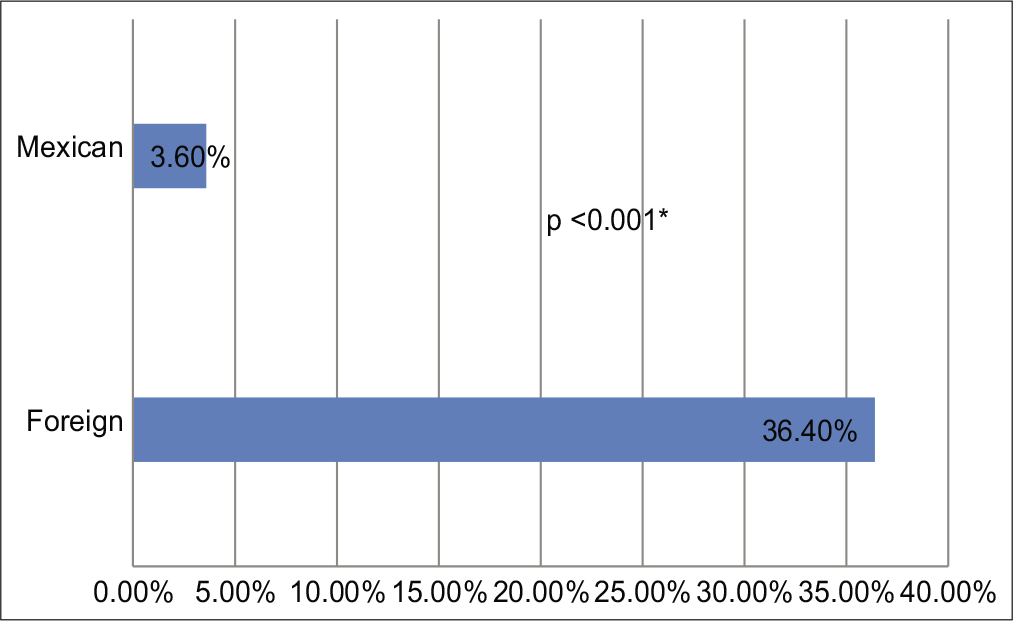

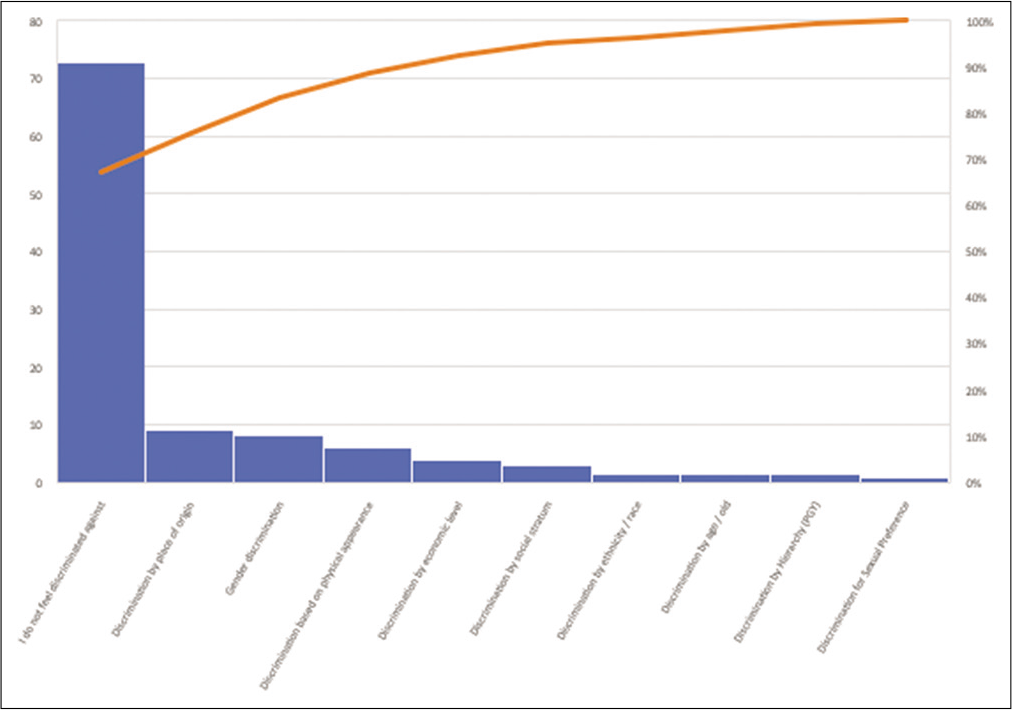

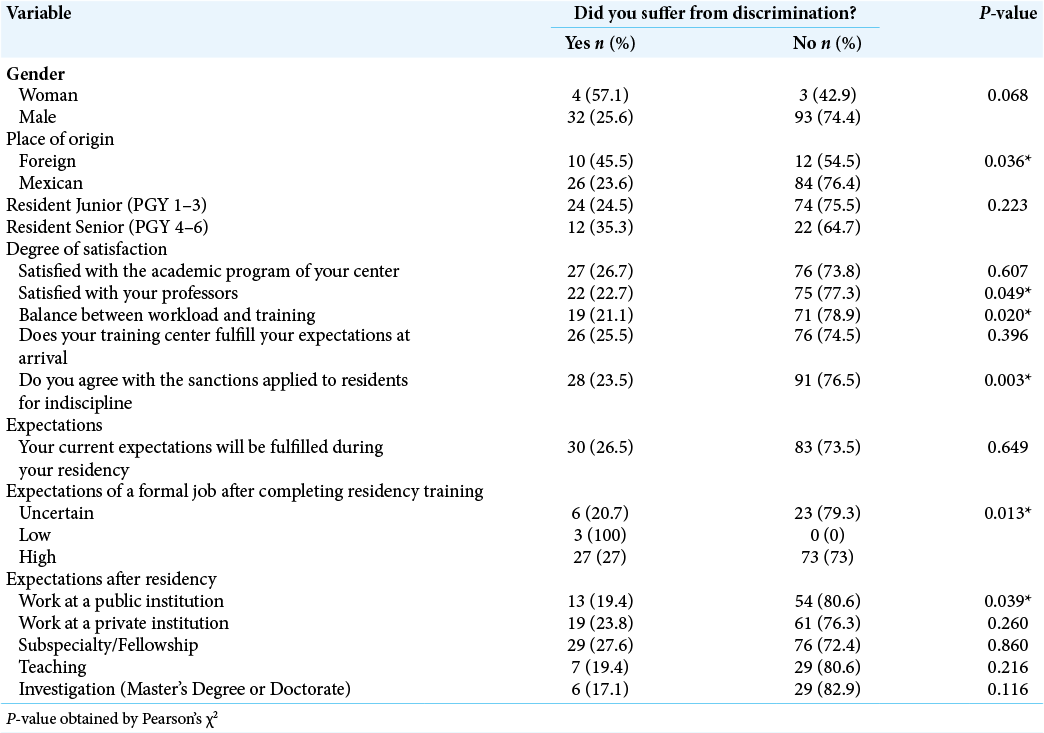

Results: A response rate of 50% (132 of 264 residents’ members of MSNS) was obtained and considered for analysis. Median age was 30.06 ± 2.48 years, 5.3% (n = 7) were female and 16.7% (n = 22) were foreigners undergoing neurosurgical training in Mexico. Approximately 27% of respondents suffered any form of discrimination, mainly by place of origin (9.1%), by gender (8.3%) or by physical appearance (6.1%). About 42.9% (n = 3) of female residents were discriminated by gender versus 6.4% (n = 8) of male residents (P = 0.001); while foreign residents mentioned having suffered 10 times more an event of discrimination by place of origin compared to native Mexican residents (36.4% vs. 3.6%, P

Conclusion: This manuscript represents the first approximation to determine the impact of discrimination suffered by residents undergoing neurosurgical training in Mexico before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Keywords: Discrimination, Mexico, Neurosurgery, Resident, Women

INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades, progress has been observed for gender equality in neurosurgery. An increase in the number of women in neurosurgical training has been expanding in North American programs including the American Board of Neurological Surgery (ABNS)[

A genuine intention for gender equality with better training opportunities and facilities has been reflected by an increased number of foreign countries residents receiving international neurosurgical training. The United States represents one of the main countries selected by residents to perform neurosurgery, and this has been reflected on published rates of up to 8.9% of foreigner doctors graduated in neurosurgery.[

Foreign residents usually have a solid research background with greater number of publications and a higher H-index compared to residents of the United States. Even though, their average match rate represents <50% for postgraduate studies in the United States.[

In Mexico, there is no history of publications evaluating the impact of discrimination suffered by residents during neurosurgical training before the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic. In this study, we applied for the 1st time a survey to evaluate the discriminatory conditions experienced by residents during their neurosurgical training in Mexico to identify areas of opportunity to improve educational conditions in our country.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data were collected from an original online survey created using Google Forms Survey. This survey was sent by email to 264 native and foreigners’ residents during neuro-surgical training in Mexico registered in the MSNS between October 2019 and July 2020. The survey consisted of 18 questions and three sections and was answered anonymously [Supplemental Appendix 1]. All results were collected in a Google forms database.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25. Descriptive analysis was made, and bivariate analysis was carried out with a Pearson’s Chi-square test. The impact of discrimination suffered by women and foreigners’ residents during neurosurgical training in Mexico was analyzed. In addition, academic and technological resources, specialty and surgical resources, number of operating rooms, monthly admissions, and number of major surgeries were analyzed to observe the impact on the degree of academic and training satisfaction, as well as current and future expectations.

RESULTS

Survey responses: Demographic information

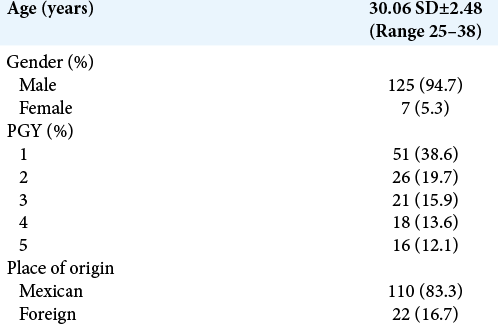

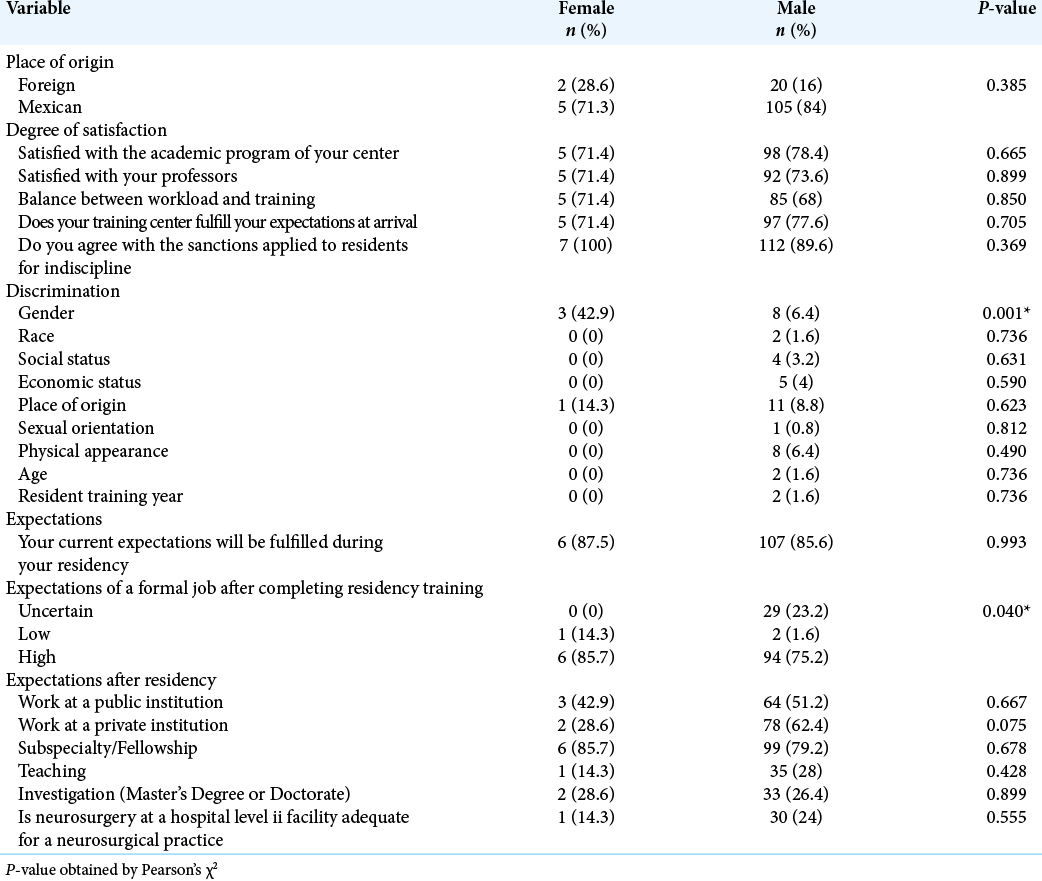

The survey was sent to 264 Mexican residents in training through email and we obtained a response rate of 51.14% (n = 135). Three surveys were eliminated due to incomplete fulfilling of all the fields required. A total of 132 responses were considered for the analysis. Median age was 30.06 ± 2.48 years, 5.3% (n = 7) were female, and 16.7% (n = 22) were foreigners. About 74.2% (n = 98) of the responders were junior residents (PGY 1-3) [

Gender: Female and male

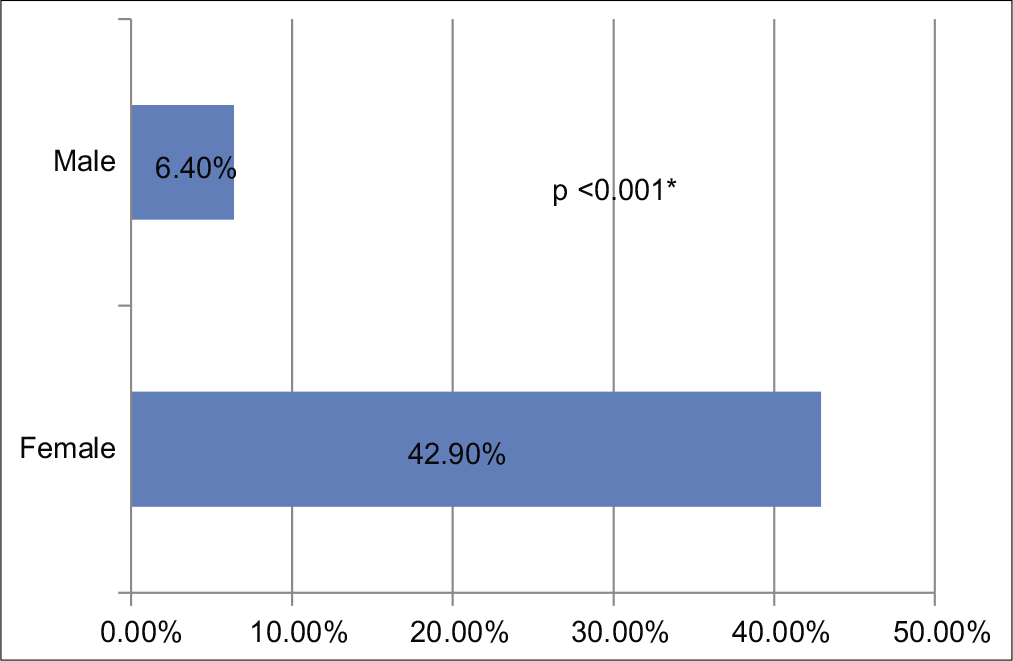

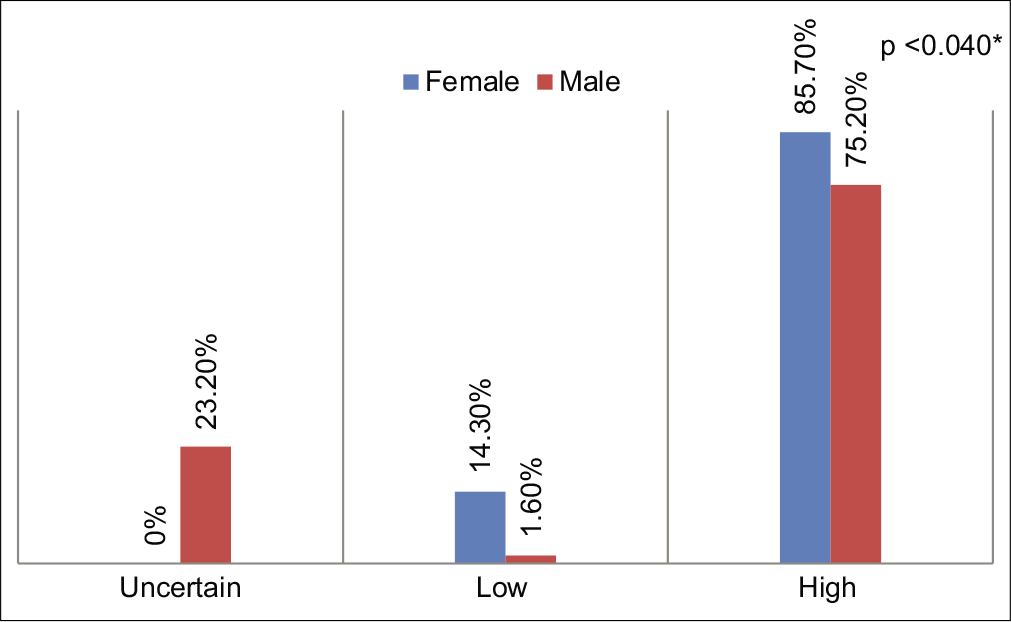

About 42.9% (n = 3) of female residents were discriminated by gender against 6.4% (n = 8) of male residents (P = 0.001) [

Place of origin: Foreign and Mexican resident trainers

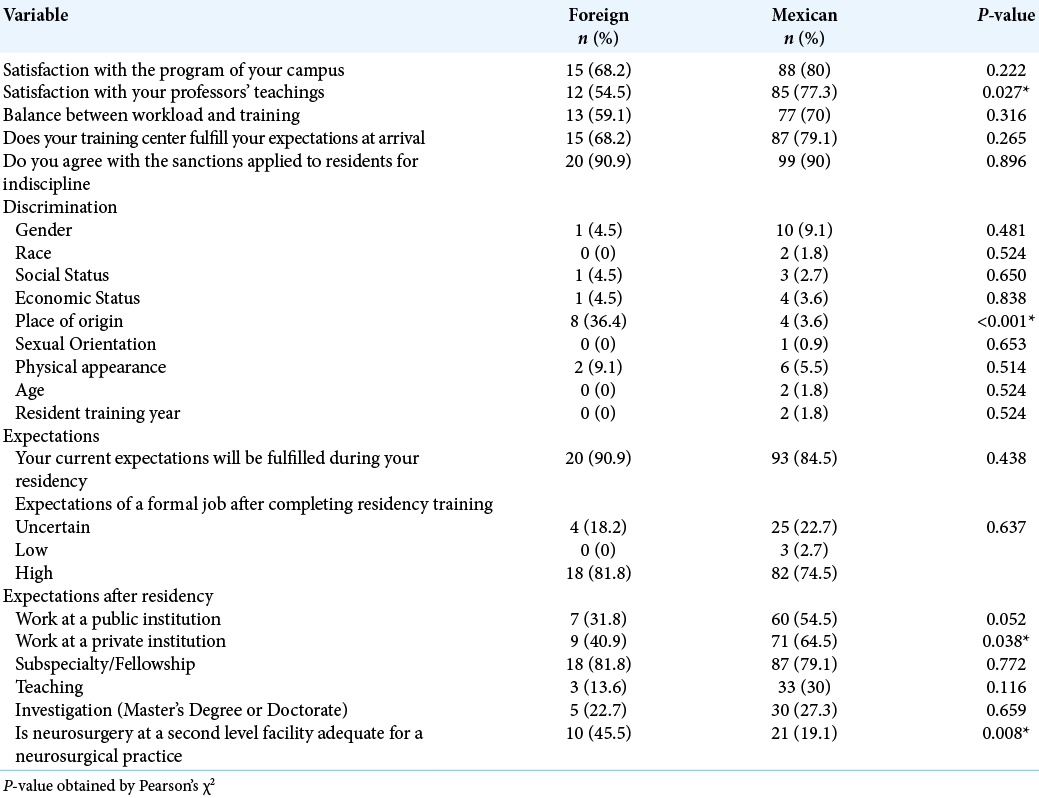

More than three-quarters of Mexican residents reported being satisfied with the tutoring of their professors compared to 54% of foreign residents (P = 0.027). Foreign residents mentioned having suffered 10 times more an event of discrimination by place of origin compared to Mexican residents (36.4% vs. 3.6%, P < 0.001) [

Junior and senior residents

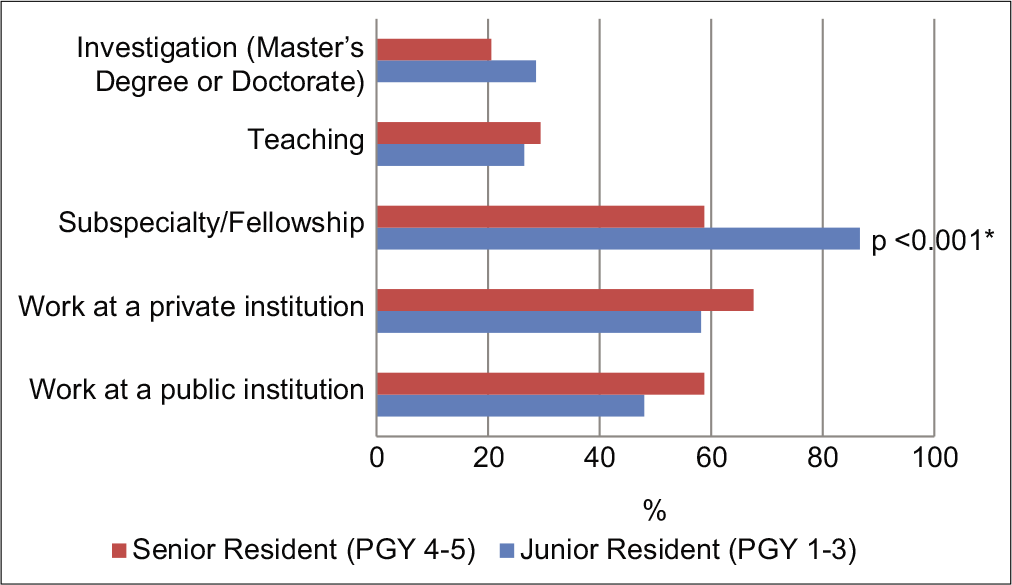

Most of the survey respondents were junior residents (74.2%). Junior residents answered that they had a predilection for taking a sub-specialty or fellowship course after completing their residency (86.7% vs. 58.8%, P = 0.001) [

Discrimination

The main causes of discrimination were discrimination by place of origin, followed by discrimination by gender and discrimination by physical appearance [

Characteristics of neurosurgical training centers

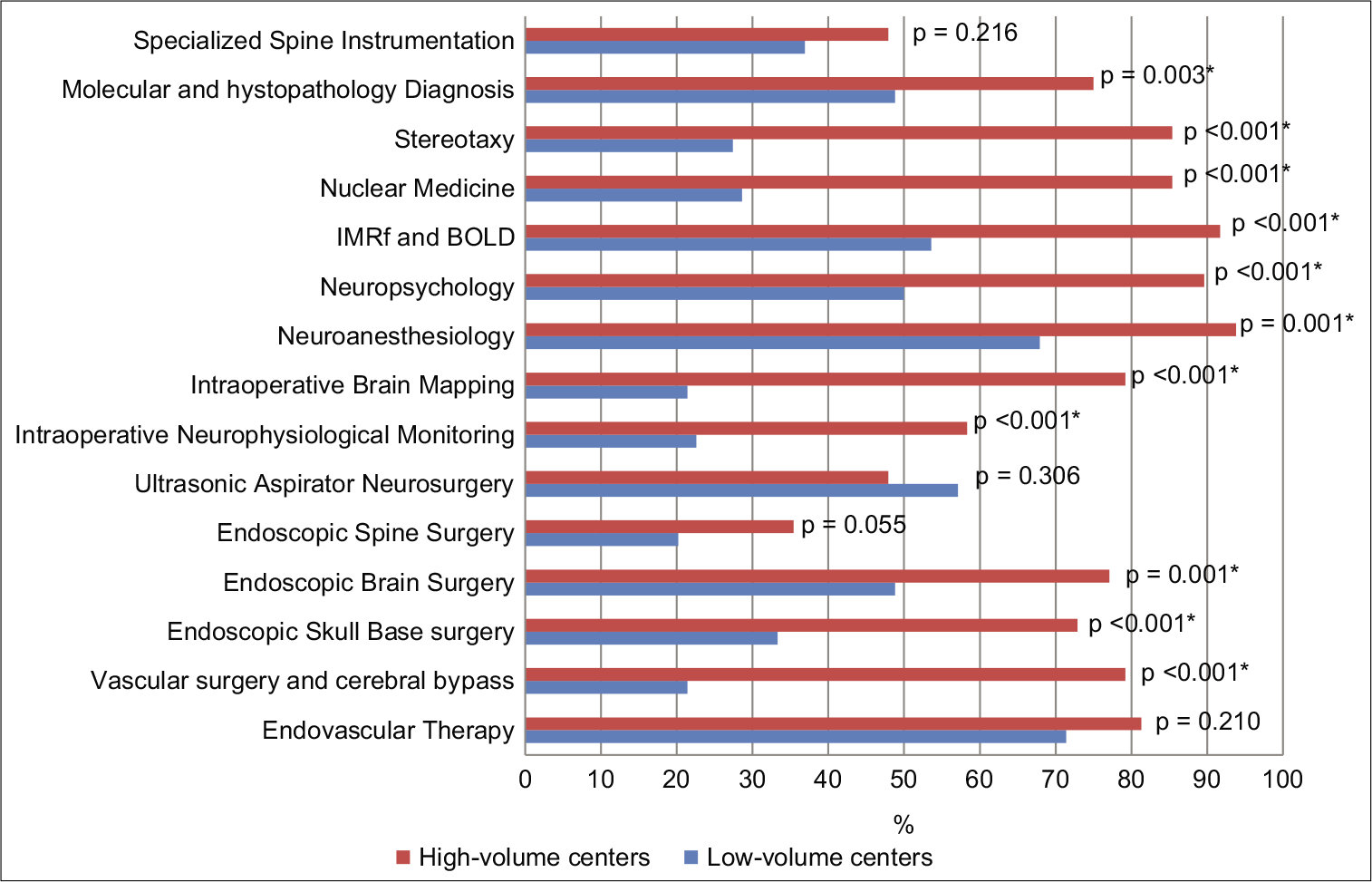

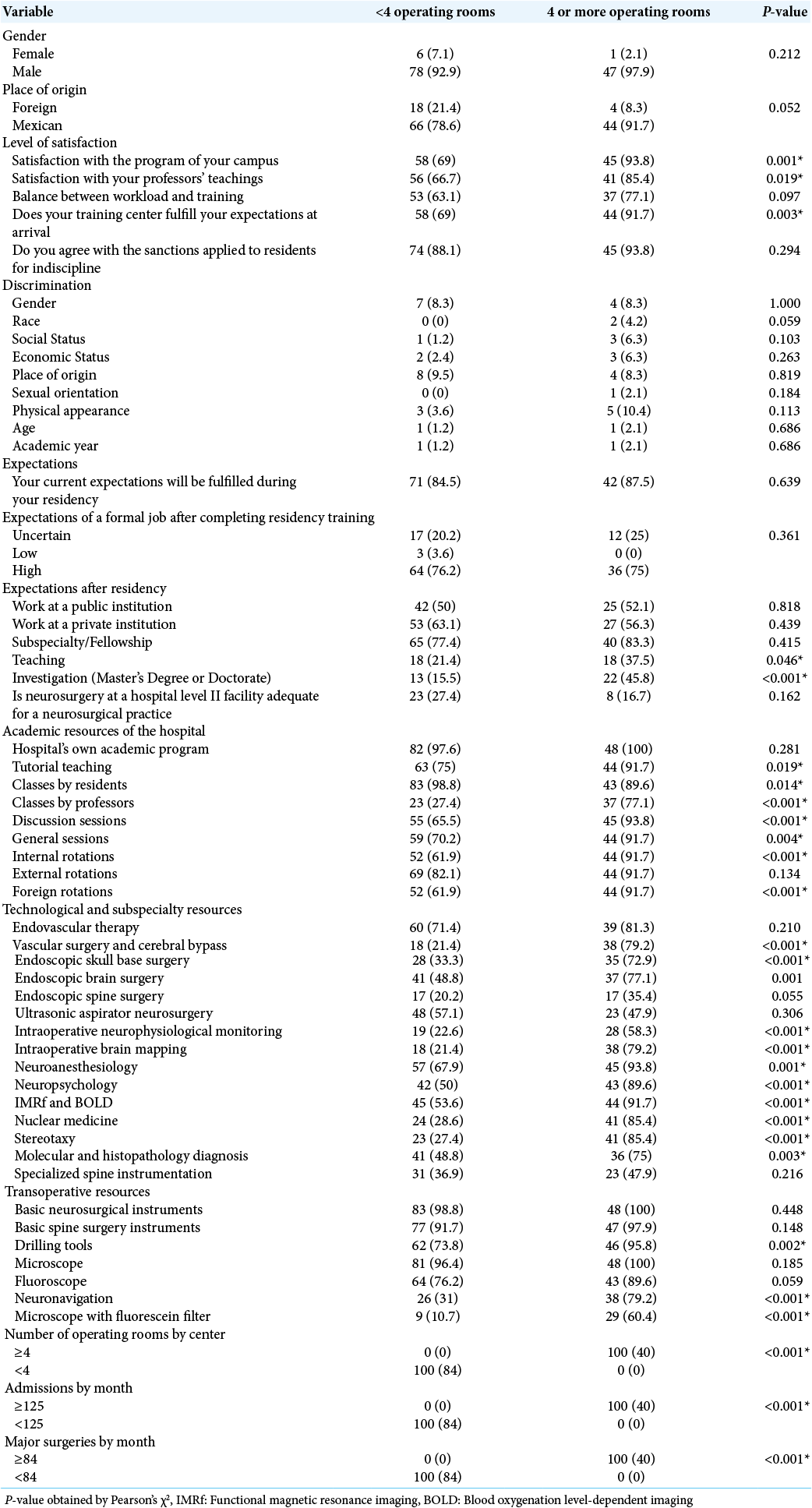

Respondents mentioned an average number of operating rooms per hospital of 2.7 SD ± 1.23 (Range 1–4), a mean of monthly admissions of 105.48 SD ± 90.5 (Range 54–200), and a mean of major surgeries performed monthly of 63.73 SD ± 33.2 (Range 21–136). We observed that centers with four operating rooms had larger educational resources, more subspecialties facilities, and a greater amount of technological resources [

DISCUSSION

Discrimination is a problem of global impact in surgical residencies. A recent study carried out in Latin America by the AO Spine Latin America association reported that only 12.11% of the members are women (n = 27). Gender discrimination is an important topic and approximately 67% of the women reported having been discriminated against by gender (66.67% vs. 1.02%) and 81% of the women mentioned being discouraged from becoming spinal surgeons or neurosurgeons (81.48% vs. 0.51%) in this study.[

Conventionally, in medical literature, neurosurgical centers have been classified into low and high volume; by the amount of patients, annual admissions, number of major surgeries performed, subspecialties or technological resources, and the number of subarachnoid hemorrhages admitted per year.[

WINS training

The ABNS reports that 66 female neurosurgeons were trained between the years 2011–2016 (an average of 11 neurosurgeons per year). Before this data, the ABNS mentions an annual rate of 7.58 neurosurgeon women trained between the years 1964 and 2013.[

Foreigner in training in neurosurgery

In our study, 16.7% of the participants were foreigners who are undergoing their neurosurgery residency in Mexico. In contrast, <9% of graduated neurosurgeons in the United States are foreigners.[

Discrimination in neurosurgery training

Despite recent advances that report an increase in the presence of WINS[

The previous studies have reported that men surpass academic and occupational productivity compared to women. We consider that these results may be biased by a gender-based discrimination and reduced presence of women in these reports.[

Several authors have documented support against discrimination experienced by WINS.[

Gender discrimination experienced by WINS has been evaluated globally. Gupta et al. (2020)[

In Mexico, the MSNS[

A perception of disadvantage for being women compared to men is clear. Factors such as a paucity of women mentors in neurosurgery, lack of work-life balance, absence of support in academic fields, perception of a reduced access to professional opportunities due to gender, and a sense of having to work harder than men for the same prestige[

Strengths and limitations of the study

In another study (De la Cerda-Vargas et al., 2021), we evaluated the impact of COVID on neurosurgery residents in Latin America and Spain.[

Due to the restricted number of women and foreigners undergoing neurosurgical training in Mexico who responded to the survey, our results do not allow us to enunciate strong conclusions. Nevertheless, this study represents an initial assessment of the problem which requires a greater number of respondents to calculate the real impact in Mexico or even in Latin America. We did not evaluate the burden of discrimination on the burnout rates suffered by residents,[

CONCLUSION

Our results determine the situational diagnosis that neurosurgery residents experienced in Mexico before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. We believe that identifying issues that our residents face on a day-to-day basis is essential to upgrade educational and social relationships. This study pretends to recognize areas of opportunity to reduce the rate of discrimination suffered by residents who receive neurosurgical training in Mexico. Specific strategies targeted to our neurosurgical community aimed at improving a balance of opportunities among residents are a priority to reduce discrimination by gender and place of origin. Our study represents the first approach to determine the impact of discrimination suffered by women and foreign residents with neurosurgical training in Mexico before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix 1: Survey

National Survey of Neurosurgery Residents in Training

Neurosurgical training center:

PGY:

Age:

Gender:

Country of Origin:

Situational diagnostic:

Has your neurosurgical training center its own academic program? Yes () Not () Is the practice in your neurosurgical training center tutorial? (Topics or cases are supervised by associate professors) Yes () Not () Choose the educational methodology of your neurosurgical training center: Monographic lectures given by a resident. Yes () Not () Monigraphic classes given by a teacher. Yes () Not (). Discussion of morbimortality cases. Yes () Not () Discussion of cases with related specialties. Yes () Not () Internal rotations. YES () Not () External rotations. Yes () Not () Foreign rotations. Yes () Not () Technological resources essential for neurosurgical training. Basic neurosurgical instruments. Yes () Not () Basic spine surgery instruments. Yes () Not () Drilling tools. Yes () Not () Microscope. Yes () Not () Fluoroscope. Yes () Not () Neuronavigation. Yes () Not () Microscope with fluorescein filter. Yes () Not () Sub-specialties technological resources Endovascular therapy. Yes () Not () Vascular surgery and cerebral bypass. Yes () Not () Endoscopic skull base surgery. Yes () Not () Endoscopic brain surgery. Yes () Not () Endoscopic spine surgery. Yes () Not () Ultrasonic aspirator neurosurgery. Yes () Not () Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring. Yes () Not () Intraoperative brain mapping. Yes () Not () Neuroanesthesiology. Yes () Not () Neuropsychology. Yes () Not () IMRF and BOLD. Yes () Not () Nuclear medicine. Yes () Not () Stereotaxy. Yes () Not () Molecular and histopathology diagnosis. Yes () Not () Specialized spine instrumentation. Yes () Not () How many operating rooms does your hospital have? _____________________________________ How many admissions per month does your training center have? _____________________________________ How many major surgeries per month are performed in your hospital? ___________________________________ Satisfaction diagnosis: Are you satisfied with the academic program of your center? Yes () Not () Are you satisfied with the instruction and tutoring of your professors? Yes () Not () Has the relationship between practice and learning an adequate balance for your learning in your center? Yes () Not () Does your neurosurgical training meet the expectations that you had before your admittance to residency? Yes () Not () Do you agree that failure to comply with obligations as a resident in training should be punished? Yes () Not () Mention if you consider yourself discriminated for any of these reasons: Gender ______ Social stratum _______ Race ________ Birthplace _______ Sexual preference _______ Physical Appearance ______ Age ______ Other (Mention the reason) ____________________ I Do not feel discriminated _________ Diagnosis of Expectations: Do you consider that your current expectations will be fulfilled during the course of your residence? Yes () Not () At the end of your residence you plan for your practice is: Working in a public institution _________ Working in a private institution _________ Subspecialty/fellowship _________ Teaching activity _________ Research activity (Includes master/doctorate) _________ Your expectations of obtaining formal job at the end of your residence are: High ________ Uncertain ________ Low _________ Do you consider that the medicine in a second level hospital in mexico allows an adequate development of the practice of neurosurgery? Yes () Not ()

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all residents, professors, Centers, and Hospitals that contribute to this project.

References

1. 2. 3. Chandra A, Aghi MK. Strategies to address projected challenges facing foreign applicants in the U. S. neurosurgery match. World Neurosurg. 2020. 138: 553-5 4. Chandra A, Brandel MG, Wadhwa H, Almeida ND, Yue JK, Nuru MO. The path to U.S. neurosurgical residency for foreign medical graduates: Trends from a decade 2007-2017. World Neurosurg. 2020. 137: e584-96 5. Cochran A, Hauschild T, Elder WB, Neumayer LA, Brasel KJ, Crandall ML. Perceived gender-based barriers to careers in academic surgery. Am J Surg. 2013. 206: 263-8 6. de la Cerda-Vargas MF, Stienen MN, Soriano-Sanchez JA, Campero A, Borba LA, Nettel-Rueda B. Impact of the Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on working and training conditions of neurosurgery residents in Latin America and Spain. World Neurosurg. 2021. 150: e182-202 7. Enchev Y, Brady Z, Arif S, Encheva E, Peev N, Ahmad M. Sexual discrimination in neurosurgery: A questionnaire-based nationwide study amongst women neurosurgeons in Bulgaria. J Neurosurg Sci. 2019. p. 8. Falavigna A, Ramos MB, de Farias FA, Britz JP, Dagostini CM, Orlandin BC. Perception of gender discrimination among spine surgeons across Latin America: A web-based survey. Spine J. 2021. p. S1529-9430(21)00182-0 9. Fujimaki T, Shibui S, Kato Y, Matsumura A, Yamasaki M, Date I. Working conditions and lifestyle of female surgeons affiliated to the Japan neurosurgical society: Findings of individual and institutional surveys. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2016. 56: 704-8 10. Gadjradj PS, Ghobrial JB, Booi SA, de Rooij JD, Harhangi BS. Mistreatment, discrimination and burn-out in neurosurgery. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2021. 202: 106517 11. Gupta M, Reichl A, Diaz-Aguilar LD, Duddleston PJ, Ullman JS, Muraszko KM. Pregnancy and parental leave among neurosurgeons and neurosurgical trainees. J Neurosurg. 2020. 134: 1325-33 12. Lu VM, Menendez I, Levi AD, Komotar RJ.editors. Letter to the editor: Lessons to learn from the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for international medical graduate applicants and United States neurosurgery residency programs. World Neurosurg. 2020. 141: 571-2 13. Mejia-Perez SI, Cervera-Martinez C, Sanchez-Correa TE, Corona-Vazquezo T. The woman in neurosurgery at the national institute of neurology and neurosurgery. Gac Med Mex. 2017. 153: 279-82 14. 15. Muehlschlegel S. Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2018. 24: 1623-57 16. Mueller C, Wright R, Girod S. The publication gender gap in US academic surgery. BMC Surg. 2017. 17: 16 17. Nassar ME. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Ann Intern Med. 2005. 142: 153 18. Palanisamy D, Battacharjee S. What it is to be a woman neurosurgeon in India: A survey. Asian J Neurosurg. 2019. 14: 808-14 19. Park J, Minor S, Taylor RA, Vikis E, Poenaru D. Why are women deterred from general surgery training?. Am J Surg. 2005. 190: 141-6 20. Renfrow JJ, Rodriguez A, Wilson TA, Germano IM, Abosch A, Wolfe SQ. Tracking career paths of women in neurosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2018. 82: 576-82 21. Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician gender effects in medical communication: A meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2002. 288: 756-64 22. Scheitler KM, Lu VM, Carlstrom LP, Graffeo CS, Perry A, Daniels DJ. Geographic distribution of international medical graduate residents in U.S. Neurosurgery training programs. World Neurosurg. 2020. 137: e383-8 23. Shaikh AT, Farhan SA, Siddiqi R, Fatima K, Siddiqi J, Khosa F. Disparity in leadership in neurosurgical societies: A global breakdown. World Neurosurg. 2019. 123: 95-102 24. Steklacova A, Bradac O, de Lacy P, Benes V. E-WIN project 2016: Evaluating the current gender situation in neurosurgery across Europe-an interactive, multiple-level survey. World Neurosurg. 2017. 104: 48-60 25. Vespa P, Diringer MN. Participants in the International Multi-Disciplinary Consensus Conference on the Critical Care Management of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. High-volume centers. Neurocrit Care. 2011. 15: 369-72 26. Wallis CJ, Ravi B, Coburn N, Nam RK, Detsky AS, Satkunasivam R. Comparison of postoperative outcomes among patients treated by male and female surgeons: A population based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2017. 359: j4366