- Department of Neurosurgery, Dokkyo Medical University Saitama Medical Center, Saitama, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Yasuhiko Nariai, Department of Neurosurgery, Dokkyo Medical University Saitama Medical Center, Saitama, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1279_2021

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Yasuhiko Nariai, Tomoji Takigawa, Akio Hyodo, Kensuke Suzuki. Distal migration of the flow-redirection endoluminal device immediately after treatment: A case report and literature review. 04-Mar-2022;13:81

How to cite this URL: Yasuhiko Nariai, Tomoji Takigawa, Akio Hyodo, Kensuke Suzuki. Distal migration of the flow-redirection endoluminal device immediately after treatment: A case report and literature review. 04-Mar-2022;13:81. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11419/

Abstract

Background: A flow diverter (FD) has been a promising endovascular therapeutic modality for challenging intracranial aneurysms. However, stent migration has been an unusual complication. Until recently, among some types of FDs, the migration of the flow-redirection endoluminal device (FRED; MicroVention Inc., Aliso Viejo, CA, USA) has almost never been reported. Herein, we report a case of acute distal migration of a single FRED secondary to in-stent thrombi with symptomatic ischemic stroke and review the literature on the distal migration of FDs.

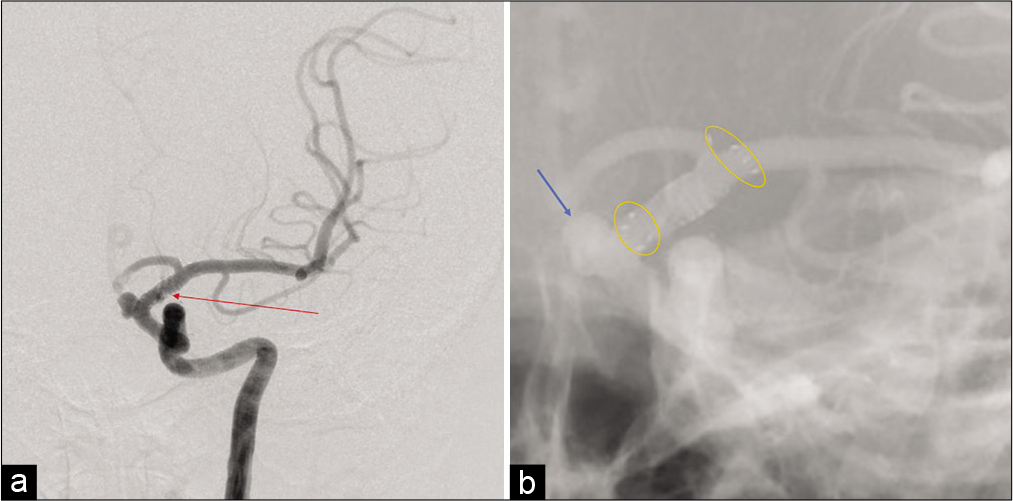

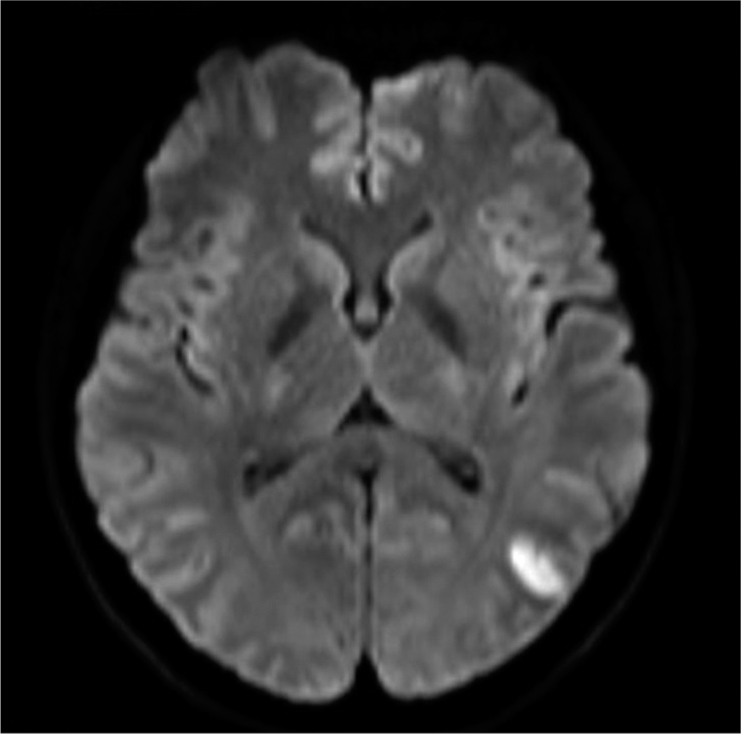

Case Description: A 35-year-old woman was diagnosed with a left unruptured internal carotid-ophthalmic artery aneurysm. A 3.5 mm diameter and 17 mm long FRED was adequately deployed. The patient awoke from general anesthesia without neurological deficits. However, shortly after the procedure, the patient presented with conjugate deviation toward the left side, right severe hemiparesis, and total aphasia. Although the symptoms gradually improved, angiography was performed. Angiography revealed some in-stent thrombi and distal migration of the FRED, and initially, one of the left M2 inferior trunk branches was occluded by an embolic thrombus. However, the thrombus spontaneously migrated distally without any specific treatment. Finally, despite leaving the migrated stent in situ, the flow almost completely improved, and the patient’s neurologic deficits disappeared. Magnetic resonance imaging following treatment revealed only a small cerebral infarction in the left temporo-occipital area.

Conclusion: Distal migration of an FD in an acute setting, including the FRED, may occur even following appropriate placement. In-stent thrombosis can cause distal stent migration and thromboembolic stroke.

Keywords: Flow diverter, Flow-redirection endoluminal device, Stent migration

INTRODUCTION

Endoluminal vessel reconstruction treatment with a flow diverter (FD) stent has been a promising endovascular therapeutic modality for challenging intracranial aneurysms at various locations. The FD is a low porosity metal stent that can decrease the velocity and pressure of intra-aneurysmal blood flow and lead to delayed thrombosis with reconstruction of the parent artery. Moreover, they provide a scaffold for endothelialization across an aneurysm neck by diverting blood flow away from the aneurysmal sac, resulting in clotting of the aneurysm.[

CASE REPORT

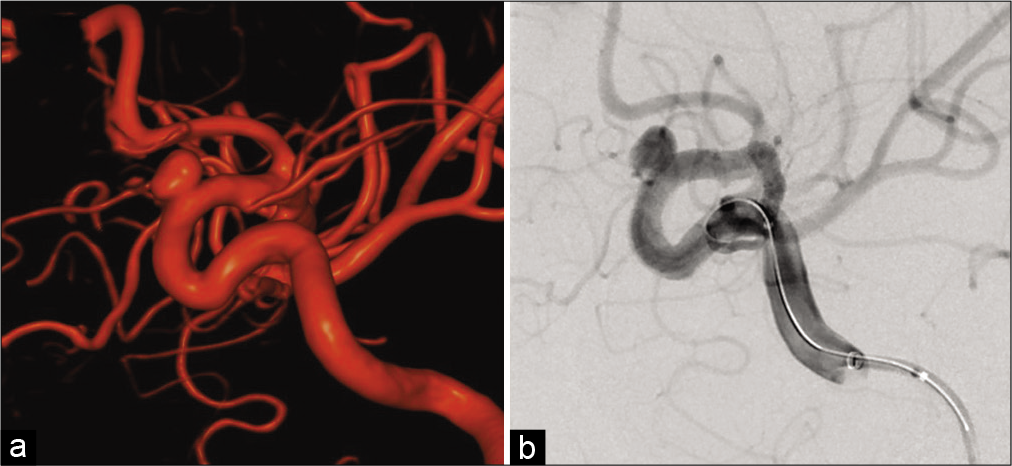

A 35-year-old woman was incidentally diagnosed with a left unruptured internal carotid-ophthalmic artery aneurysm with a maximum size of 6.1 mm and neck size of 3.6 mm [

Under general anesthesia, a 7-French shuttle sheath (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was placed with a coaxial system at the cervical portion of the left internal carotid artery (ICA) through the right femoral site. A Headway27 microcatheter (MicroVention Inc.) was navigated distal to the aneurysm using a microguidewire (ASAHI CHIKAI 14; Asahi Intecc Co., Ltd., Aichi, Japan). Moreover, the SOFIA SELECT EX (MicroVention Inc.) was used as a distal access catheter. The size of the FRED was determined according to the diameter of the ICA vessel proximal (3.3 mm) and distal (3.2 mm) to the aneurysm. A 3.5 mm diameter and 17 mm long FRED was adequately deployed through the microcatheter across the neck of the aneurysm under appropriate therapeutic heparinization [

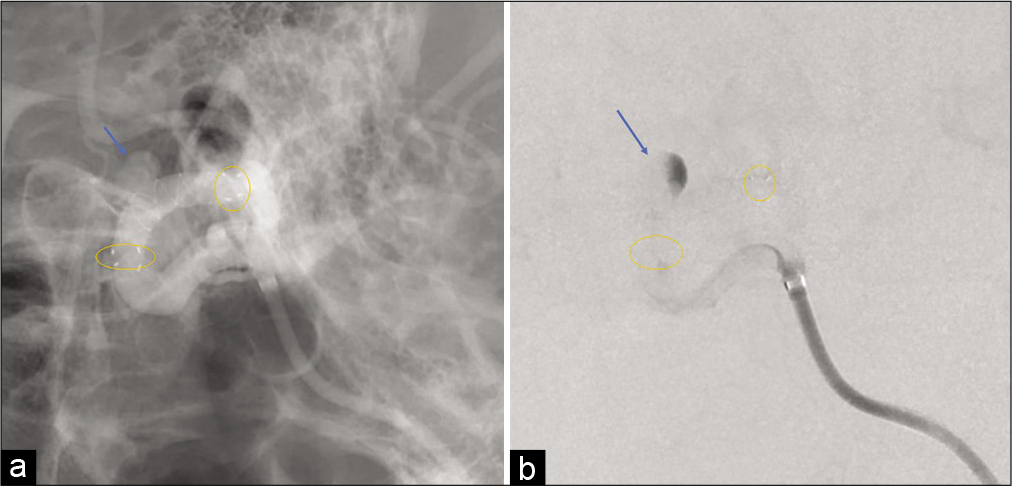

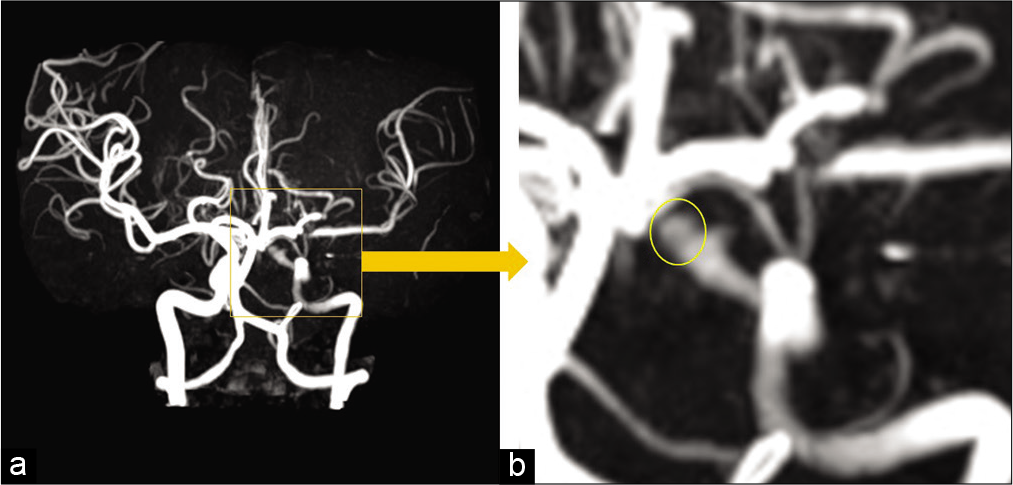

However, only 1 h following the procedure, the patient presented with conjugate deviation toward the left side, right severe hemiparesis, and total aphasia. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed no evident acute cerebral infarction. However, magnetic resonance angiography revealed the aneurysm, which meant that the FD was no longer covering the aneurysm. Furthermore, a signal defect of the left ICA terminus, which meant that the FD was located there, and decline of the flow of the left peripheral middle cerebral artery (MCA) [

Figure 3:

Magnetic resonance angiography shortly after the flow-redirection endoluminal device deployment and occurrence of the neurological deficits (a) revealed the aneurysm (yellow circle) and signal defect of the left internal carotid artery terminus with decline of the left peripheral middle cerebral artery (b).

DISCUSSION

This case report describes the acute distal migration of a single FRED resulting from in-stent thrombi causing ischemic stroke. Among FD migration cases, FRED migration has almost never been reported. Furthermore, the clinical appearance of the neurologic symptoms enabled extremely early confirmation of the stent migration shortly after treatment.

Spontaneous migrations of the FD have been reported both early and late, that is, from immediately after treatment to 14 months following treatment.[

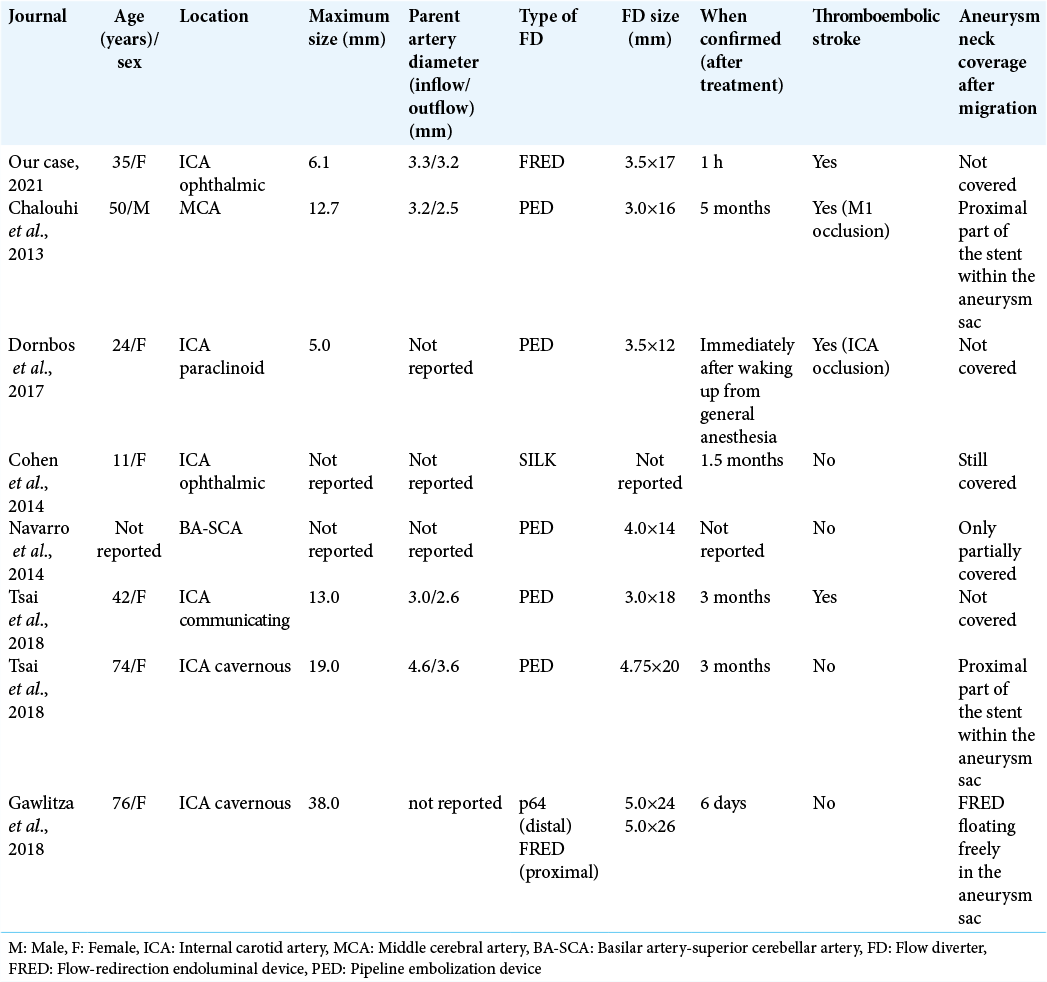

Compared with proximal migration, distal migration of an FD is rare. Apart from our case, seven cases of distal FD migration have been identified in the literature [

Among all types of FDs, the FRED is the only dual-layered type nitinol device consisting of a low porosity inner mesh with higher pore attenuation (48 nitinol wires) and an outer stent with high porosity (16 nitinol wires). An interwoven double helix of radiopaque tantalum strands attaches the inner mesh to the outer stent and improves visibility over its full length of dual-layer coverage.[

CONCLUSION

Distal migration of an FD in an acute setting, including the FRED, may occur even following appropriate placement. In-stent thrombosis can cause distal stent migration and thromboembolic stroke.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Ajadi E, Kabir S, Cook A, Grupke S, Alhajeri A, Fraser JF. Predictive value of platelet reactivity unit (PRU) value for thrombotic and hemorrhagic events during flow diversion procedures: A meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019. 11: 1123-8

2. Chalouhi N, Satti SR, Tjoumakaris S, Dumont AS, Gonzalez LF, Rosenwasser R. Delayed migration of a pipeline embolization device. Neurosurgery. 2013. 72: ons229-34

3. Chalouhi N, Tjoumakaris SI, Gonzalez LF, Hasan D, Pema PJ, Gould G. Spontaneous delayed migration/shortening of the pipeline embolization device: Report of 5 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013. 34: 2326-30

4. Cohen JE, Gomori JM, Moscovici S, Leker RR, Itshayek E. Delayed complications after flow-diverter stenting: reactive in-stent stenosis and creeping stents. J Clin Neurosci. 2014. 21: 1116-22

5. Dornbos D, Powers CJ. Acute distal migration of a flow diverting stent. J Clin Neurosci. 2017. 44: 223-5

6. Gawlitza M, Soize S, Manceau PF, Pierot L. Delayed intraaneurysmal migration of a flow diverter construct after treatment of a giant aneurysm of the cavernous internal carotid artery. J Neuroradiol. 2020. 47: 233-6

7. Girdhar G, Andersen A, Pangerl E, Jahanbekam R, Ubl S, Nguyen K. Thrombogenicity assessment of Pipeline Flex, Pipeline Shield, and FRED flow diverters in an in vitro human blood physiological flow loop model. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2018. 106: 3195-202

8. Griessenauer CJ, Thomas AJ, Enriquez-Marulanda A, Deshmukh A, Jain A, Ogilvy CS. Comparison of pipeline embolization device and flow re-direction endoluminal device flow diverters for internal carotid artery aneurysms: A propensity score-matched cohort study. Neurosurgery. 2019. 85: E249-55

9. Hagen MW, Girdhar G, Wainwright J, Hinds MT. Thrombogenicity of flow diverters in an ex vivo shunt model: Effect of phosphorylcholine surface modification. J Neurointerv Surg. 2017. 9: 1006-11

10. Jabbour P, Atallah E, Chalouhi N, Tjoumakaris S, Rosenwasser RH. A case of pipeline migration in the cervical carotid. J Clin Neurosci. 2019. 59: 344-6

11. Leung GK, Tsang AC, Lui WM. Pipeline embolization device for intracranial aneurysm: A systematic review. Clin Neuroradiol. 2012. 22: 295-303

12. Möhlenbruch MA, Herweh C, Jestaedt L, Stampfl S, Schönenberger S, Ringleb PA. The FRED flow-diverter stent for intracranial aneurysms: clinical study to assess safety and efficacy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015. 36: 1155-61

13. Navarro R, Cano EJ, Brasiliense LB, Dabus G, Hanel RA. Fatal outcome after delayed pipeline embolization device migration for the treatment of a giant superior cerebellar artery aneurysm: technical note for complication avoidance. Open J Mod Neurosurg. 2014. 4: 6

14. Sim SC, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Update on allele nomenclature for human cytochromes P450 and the human cytochrome P450 allele (CYP-allele) nomenclature database. Methods Mol Biol. 2013. 987: 251-9

15. Takong W, Kobkitsuksakul C. Delayed proximal flow diverting stent migration in a ruptured intracranial aneurysm: A case report. Neurointervention. 2020. 15: 154-7

16. Tsai YH, Wong HF, Hsu SW. Endovascular management of spontaneous delayed migration of the flow-diverter stent. J Neuroradiol. 2020. 47: 38-45