- Departments of Neurosurgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University, Japan.

- Department of Neurosurgical Engineering and Translational Neuroscience, Graduate School of Biomedical Engineering, Tohoku University, Japan.

- Departments of Neurosurgical Engineering and Translational Neuroscience, Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University, Japan.

- Department of Neurosurgery, Kohnan Hospital, Sendai, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Hidenori Endo

Departments of Neurosurgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_588_2019

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Keisuke Sasaki, Hidenori Endo, Kuniyasu Niizuma, Yasuo Nishijima, Shinichiro Osawa, Miki Fujimura, Teiji Tominaga. Efficacy of intra-arterial indocyanine green angiography for the microsurgical treatment of dural arteriovenous fistula: A case report. 13-Mar-2020;11:46

How to cite this URL: Keisuke Sasaki, Hidenori Endo, Kuniyasu Niizuma, Yasuo Nishijima, Shinichiro Osawa, Miki Fujimura, Teiji Tominaga. Efficacy of intra-arterial indocyanine green angiography for the microsurgical treatment of dural arteriovenous fistula: A case report. 13-Mar-2020;11:46. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/9896/

Abstract

Background: In this study, we report a case of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) that was successfully treated using intra-arterial indocyanine green (IA-ICG) videoangiography during open surgery. Moreover, the findings of IA-ICG videoangiography were compared with those of intraoperative digital subtraction angiography (DSA).

Case Description: A 72-year-old male patient with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and thrombocytosis presented with generalized seizure. DSA revealed Cognard Type III dAVF in the superior wall of the left transverse sinus, which was fed by a single artery (the left occipital artery [OA]) and drained into a single vein (the left temporal cortical vein), without drainage into a venous sinus. Since transarterial embolization was considered challenging due to the tortuosity of the left OA, surgical interruption of the shunt was performed by craniotomy. After excising the feeding artery, we were unable to observed dAVF on intraoperative DSA. However, IA-ICG videoangiography revealed the remaining shunt, which was fed by the collateral route from the feeding artery. The shunting point and draining vein were then surgically resected to eliminate the shunt. The shunt was not observed during the second IA-ICG videoangiography conducted after resection.

Conclusion: ICG videoangiography is a better method compared with DSA in terms of visualizing fine vascular lesions. In contrast to the typical intravenous administration, selective IA-ICG can be repeatedly injected at a minimal dose. IA-ICG is a useful intraoperative tool that can be used to evaluate the elimination of the dAVF.

Keywords: Digital subtraction angiography, Dural arteriovenous fistula, Indocyanine green, Intra-arterial injection

INTRODUCTION

Dural arteriovenous fistulas (dAVFs) are defined as abnormal connections between arterial feeders and a dural venous sinus or leptomeningeal vein. The cortical venous reflux of intracranial dAVFs can cause intracranial hemorrhage or neurological deficit due to venous hypertension.[

CASE REPORT

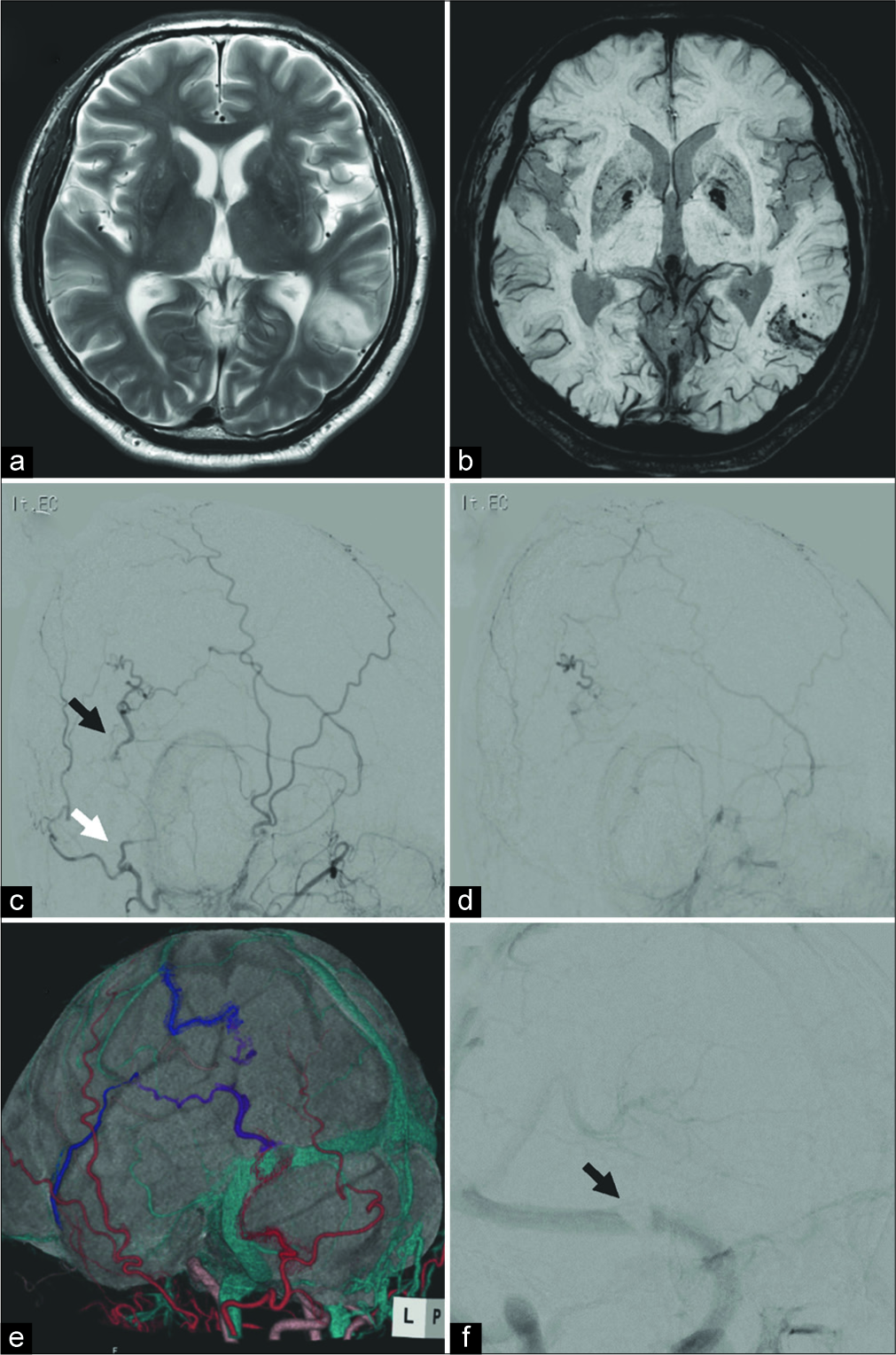

A 72-year-old male patient who had a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and thrombocytosis presented with generalized seizure. T2-wighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at admission revealed focal edema in the left posterior temporal lobe [

Figure 1:

(a) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing focal edema in the left temporal lobe. (b) Susceptibility- weighted imaging revealing microbleed in the same area. (c) Preoperative left external carotid artery angiography showing Borden Type III dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) in the left transverse sinus. White arrow indicates the feeding artery and black arrow indicates a shunting point. (d) Early venous phase of angiography demonstrating cortical venous reflux without the transverse sinus. (e) Fusion image of three-dimensional computed tomography angiography and MRI showing the detailed structure of the dAVF, consisting the occipital artery (red), cortical vein reflux (purple), and draining vein (blue). (f) Preoperative left internal carotid artery angiography showing sinus thrombosis in the left transverse sinus adjacent to the shunting point (f, black arrow).

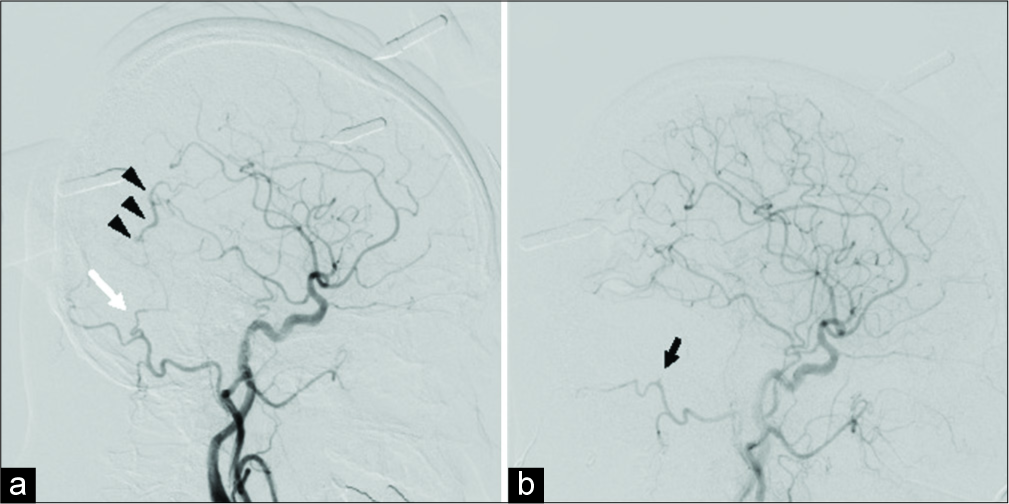

After the induction of general anesthesia, a 4-F catheter was placed in the left common carotid artery (CCA) through the right radial artery. Then, the patient was placed in prone position. Left CCA angiography that was performed before craniotomy revealed the presence of dAVF [

Figure 2:

(a) Intraoperative left common carotid artery angiography performed before craniotomy showing the occipital artery (OA) (white arrow) and cortical venous reflux (black arrowheads). (b) Angiography conducted after craniotomy revealing the disappearance of the shunt and interrupted OA (black arrow).

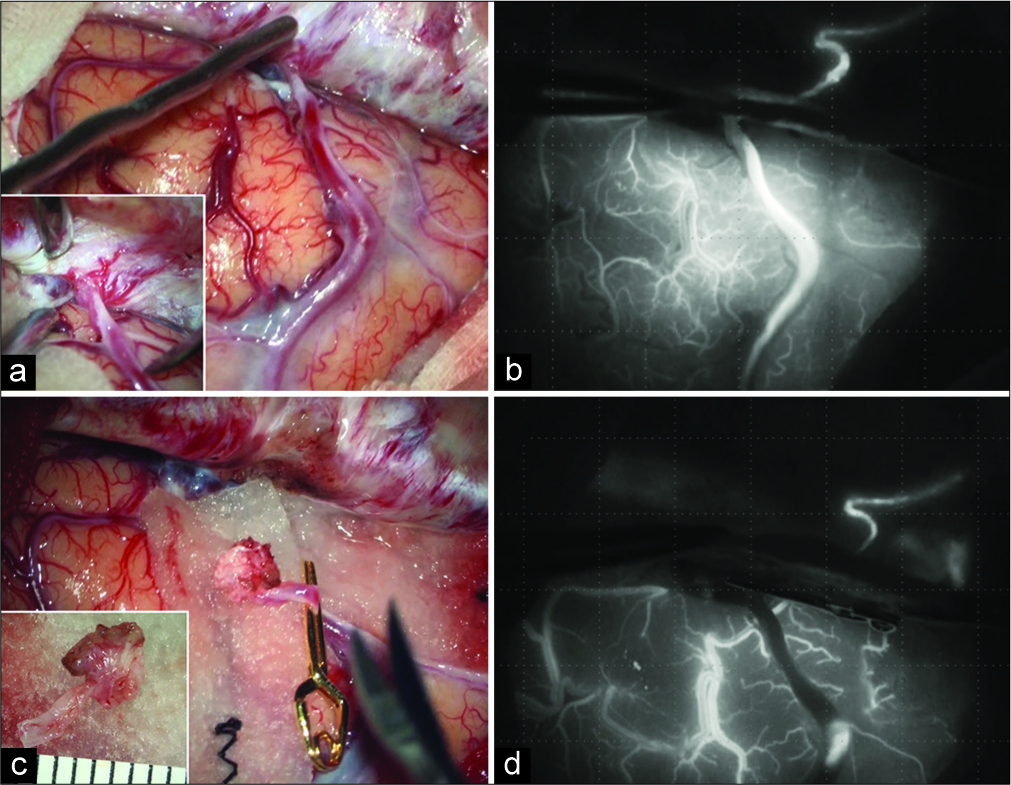

Figure 3:

(a) Intraoperative microscopic view showing the red draining vein and accumulation of the dural arteries around the shunting point. (b) Indocyanine green (ICG) videoangiography revealing the remaining shunt. (c) Clip application to the origin of the draining vein. (d) ICG videoangiography showing the disappearance of the venous reflux.

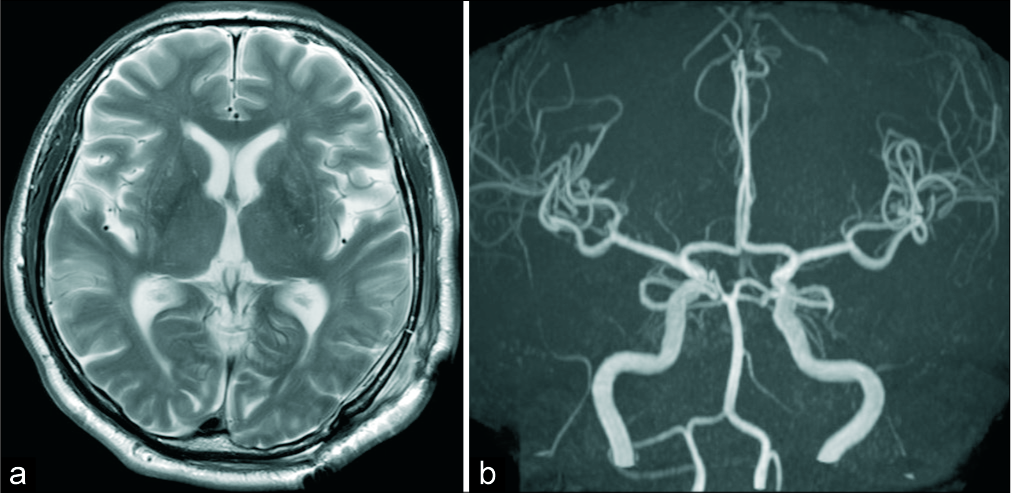

Postoperative T2-weighted MRI revealed rapid improvement of the edema [

DISCUSSION

Transvenous embolization (TVE) is considered more effective compared with transarterial embolization (TAE) in the endovascular treatment of dAVF.[

Intraoperative imaging is important in evaluating the effect of treatment during cerebrovascular microsurgery.[

In this study, we performed IA-ICG angiography through selective catheterization to the left CCA. Some reports have suggested that IA-ICG angiography uses a minimum dose of ICG; thus, it has a short washout period and facilitates repeat examinations.[

Only a few reports have compared ICG and DSA intraoperatively. Hardesty et al. have retrospectively compared DSA alone and ICG videoangiography combined with DSA.[

No study has compared IA-ICG and DSA in a single case of intracranial lesion. In our case, IA-ICG videoangiography revealed the remaining shunt, which was not observed on intraoperative DSA. Thus, IA-ICG angiography is a useful intraoperative imaging tool for dAVF surgery because one can clearly visualize fine vascular structures with it, and it can be performed repeatedly. However, its application is limited to superficial structures.

CONCLUSION

Herein, we report a case of dAVF that was successfully treated using IA-ICG videoangiography during open surgery. IA-ICG videoangiography showed the presence of residual shunt, which could not be detected on intraoperative DSA. Thus, the procedure is a useful intraoperative tool as it assists in clearly visualizing fine vascular structures and can be conducted repeatedly, thereby providing real-time information during intracranial vascular surgery.

Declaration of patient consent

Patients consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 17K10816).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Bilbao CJ, Bhalla T, Dalal S, Patel H, Dehdashti AR. Comparison of indocyanine green fluorescent angiography to digital subtraction angiography in brain arteriovenous malformation surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2015. 157: 351-9

2. Chiang VL, Gailloud P, Murphy KJ, Rigamonti D, Tamargo RJ. Routine intraoperative angiography during aneurysm surgery. J Neurosurg. 2002. 96: 988-92

3. Davies MA, TerBrugge K, Willinsky R, Coyne T, Saleh J, Wallace MC. The validity of classification for the clinical presentation of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas. J Neurosurg. 1996. 85: 830-7

4. Fox IJ, Wood EH. Indocyanine green: Physical and physiologic properties. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1960. 35: 732-44

5. Hardesty DA, Thind H, Zabramski JM, Spetzler RF, Nakaji P. Safety, efficacy, and cost of intraoperative indocyanine green angiography compared to intraoperative catheter angiography in cerebral aneurysm surgery. J Clin Neurosci. 2014. 21: 1377-82

6. Horie N, So G, Debata A, Hayashi K, Morikawa M, Suyama K. Intra-arterial indocyanine green angiography in the management of spinal arteriovenous fistulae: Technical case reports. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012. 37: E264-7

7. Kakarla UK, Deshmukh VR, Zabramski JM, Albuquerque FC, McDougall CG, Spetzler RF. Surgical treatment of high-risk intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulae: Clinical outcomes and avoidance of complications. Neurosurgery. 2007. 61: 447-57

8. Killory BD, Nakaji P, Gonzales LF, Ponce FA, Wait SD, Spetzler RF. Prospective evaluation of surgical microscope-integrated intraoperative near-infrared indocyanine green angiography during cerebral arteriovenous malformation surgery. Neurosurgery. 2009. 65: 456-62

9. Kim B, Jeon P, Kim K, Kim S, Kim H, Byun HS. Predictive factors for response of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas to transarterial onyx embolization: Angiographic subgroup analysis of treatment outcomes. World Neurosurg. 2016. 88: 609-18

10. Kuwayama N, Kubo M, Endo S, Sakai N. Present status in the treatment of dural arteriovenous fistulas in Japan. Jpn J Neurosurg. 2011. 20: 12-9

11. Lopez KA, Waziri AE, Granville R, Kim GH, Meyers PM, Connolly ES. Clinical usefulness and safety of routine intraoperative angiography for patients and personnel. Neurosurgery. 2007. 61: 724-9

12. Osanai T, Hida K, Asano T, Seki T, Sasamori T, Houkin K. Ten-year retrospective study on the management of spinal arteriovenous lesions: Efficacy of a combination of intraoperative digital subtraction angiography and intraarterial dye injection. World Neurosurg. 2017. 104: 841-7

13. Raabe A, Beck J, Gerlach R, Zimmermann M, Seifert V. Near-infrared indocyanine green video angiography: A new method for intraoperative assessment of vascular flow. Neurosurgery. 2003. 52: 132-9

14. Roy D, Raymond J. The role of transvenous embolization in the treatment of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas. Neurosurgery. 1997. 40: 1133-41

15. Tang G, Cawley CM, Dion JE, Barrow DL. Intraoperative angiography during aneurysm surgery: A prospective evaluation of efficacy. J Neurosurg. 2002. 96: 993-9