- Department of Neurosurgery, International University of Health and Welfare, School of Medicine, Narita Hospital, Narita,

- Department of Neurology, International University of Health and Welfare, School of Medicine, Narita Hospital, Narita,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Imari Arita Kyoritsu Hospital, Arita, Japan

- Department of Neurosurgery, Shiroishi Kyoritsu Hospital, Shiroishi, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Tatsuya Tanaka, Department of Neurosurgery, International University of Health and Welfare, School of Medicine, Narita Hospital, Narita, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1084_2022

Copyright: © 2023 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Tatsuya Tanaka1, Hirofumi Goto2, Nobuaki Momozaki3, Eiichiro Honda4. Endoscopic hematoma evacuation for acute subdural hematoma with improvement of the visibility of the subdural space and postoperative management using an intracranial pressure sensor. 06-Jan-2023;14:1

How to cite this URL: Tatsuya Tanaka1, Hirofumi Goto2, Nobuaki Momozaki3, Eiichiro Honda4. Endoscopic hematoma evacuation for acute subdural hematoma with improvement of the visibility of the subdural space and postoperative management using an intracranial pressure sensor. 06-Jan-2023;14:1. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=12099

Abstract

Background: The first choice to treat acute subdural hematoma (ASDH) is large craniotomy under general anesthesia. However, increasing age or the comorbid burden of patients may render invasive treatment strategy inappropriate. These medically frail patients with ASDH may benefit from a combination of small craniotomy and endoscopic hematoma removal, which is less invasive. We proposed covering with protective sheets to prevent brain injury due to contact with the endoscope and suction cannula and improve visualization of the subdural space. Moreover, we placed an intracranial pressure (ICP) sensor after endoscopic hematoma removal. In this article, we attempted to clarify the use of small craniotomy evacuation with endoscopy for ASDH.

Methods: Between January 2015 and December 2019, nine patients with ASDH underwent hematoma evacuation with endoscopy at our hospital. ASDH was removed using a suction tube with the aid of a rigid endoscope through the small craniotomy (5–6 cm). Improvement of the clinical symptoms and procedure-related complications was evaluated.

Results: No procedure-related hemorrhagic complications were observed. The outcomes of our endoscopic surgery were satisfactory without complications or rebleeding. The outcomes were not inferior to those of other reported endoscopic surgeries.

Conclusion: The results suggest that small craniotomy evacuation with endoscopy and postoperative management using an ICP sensor is a safe, effective, and minimally invasive treatment approach for ASDH in appropriately selected cases.

Keywords: Acute subdural hematoma, Endoscopic hematoma evacuation, Intracranial pressure, Minimally invasive, Small craniotomy, Surgical technique, Traumatic brain injury

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic acute subdural hematoma (ASDH) is a major clinical entity among traumatic brain injuries. Its operative management usually includes cranioplastic craniotomy, large decompressive craniectomy, trephination/craniectomy, or a combination of these procedures under general anesthesia. However, craniotomy or decompressive craniectomy has risks of blood loss and infection, making these procedures inappropriate in some cases, particularly the elderly or patients with comorbidities. Recently, reports on endoscopic hematoma removal with small craniotomy for ASDH have been increasing.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between 2015 and 2019, nine patients with ASDH (defined as a hematoma that develops within 3 days from the time of injury) who underwent endoscopic hematoma evacuation surgery were analyzed. The patients’ baseline characteristics, including age, sex, comorbidities, preoperative use of antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents, and initial neurological state as assessed using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), were retrieved from the medical records. The duration of the procedure and the type of anesthesia (general or local) were reviewed in the surgical records and videos.

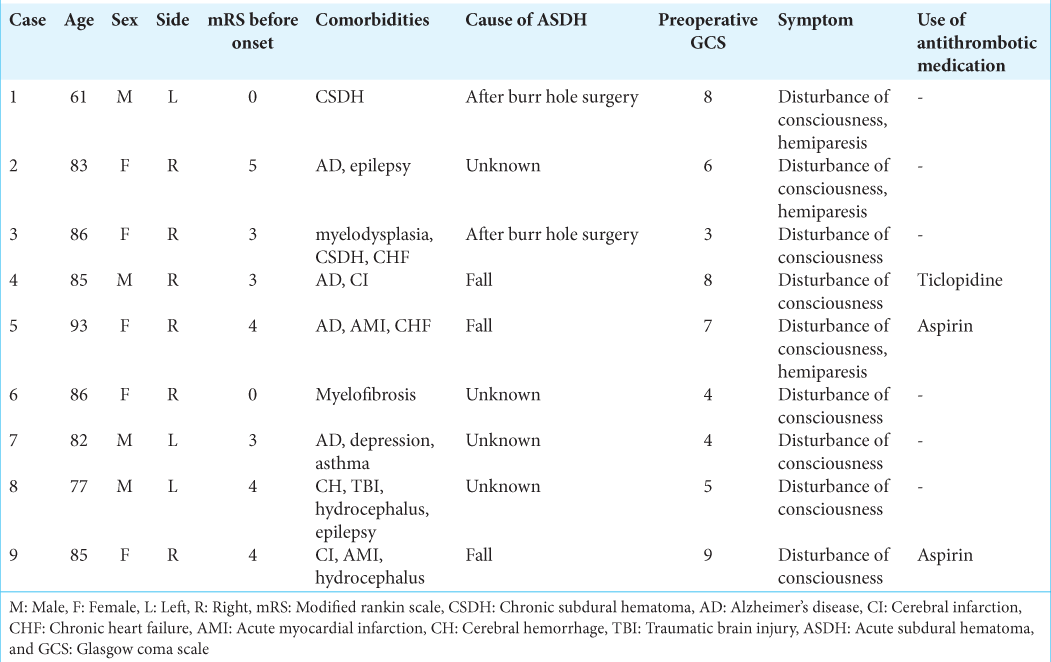

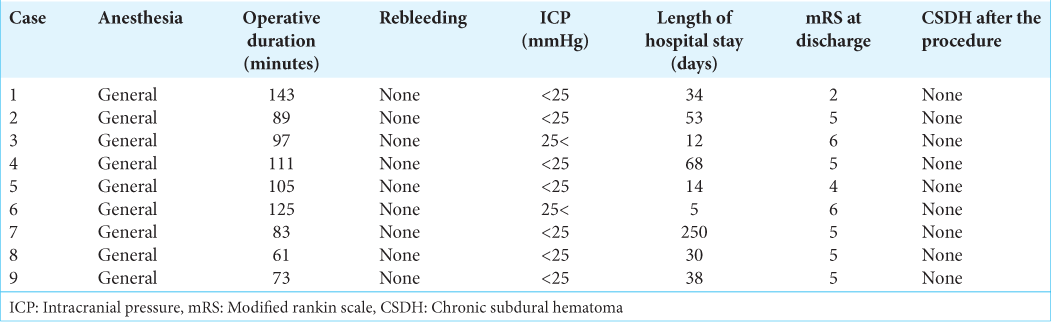

The clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in

Large craniotomy or craniectomy is typically the first-choice treatment for acute and subacute ASDH. Endoscopic hematoma evacuation was performed for ASDH in carefully selected patients. The indications for endoscopic surgery were as follows: (1) the presence of symptoms and (2) the absence of moderate or massive brain contusion/hematoma.

Endoscopic procedure

We performed endoscopic ASDH removal under general anesthesia for patients meeting the aforementioned criteria. However, we also prepared for conversion to craniotomy under general anesthesia in case the brain expanded rapidly or hemostasis was endoscopically difficult.

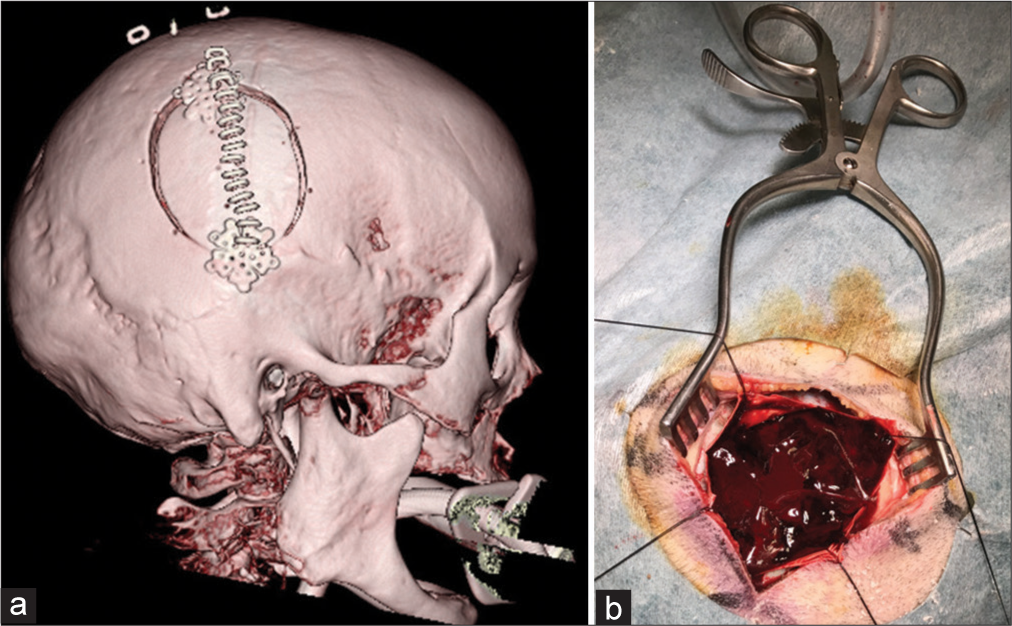

The patients’ head was rotated contralateral to the hematoma side and placed on a horseshoe headrest. An approximately 8–10-cm linear skin incision was made parallel to the coronal suture, and small craniotomy of 5–6 cm in diameter was made on the point under which the hematoma thickness was the largest [

Figure 1:

(a) Three-dimensional computed tomography shows the cranial bone after the procedure. An approximately 8-cm linear skin incision was made parallel to the coronal suture, and small craniotomy of 5–6 cm in diameter was made on the point under which the hematoma thickness was largest. (b) Small craniotomy was performed at the thickest point of the hematoma to insert the endoscope.

When bleeding from a vessel on the brain surface was observed, the suction cannula was placed at the bleeding point, and the bleeding vessel was coagulated using bipolar forceps.

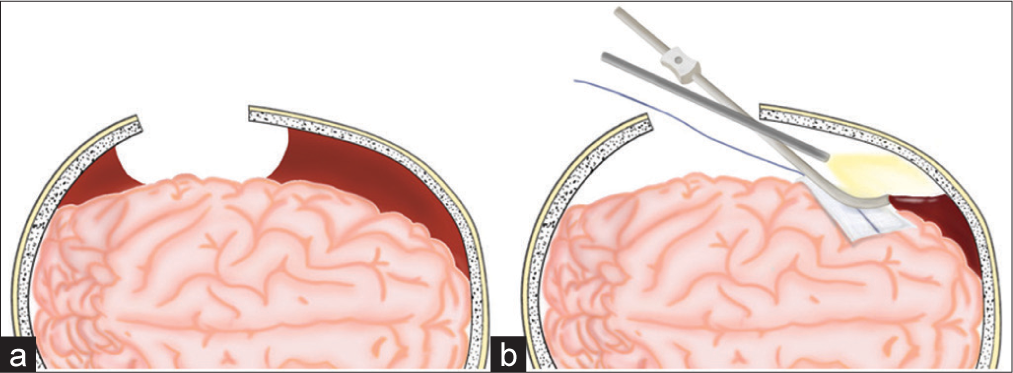

Figure 3:

Illustrative schema of our procedure. (a) After a small 5-cm-diameter craniotomy and dural incision were made, a subdural hematoma just below and around the craniotomy is evacuated. (b) The brain surface is covered with protective sheets. A rigid endoscope and surgical instruments, such as a bipolar coagulator, suction cannula, or forceps, are inserted into the subdural space to evacuate the remaining subdural hematoma and stop bleeding.

Hematoma evacuation success was evaluated using head CT.

Postoperative management

All patients underwent follow-up CT imaging immediately and 1 week after the operation. If required, craniotomy was performed on the occurrence of ICP >25 mmHg, despite drug treatment. Although antiplatelet or anticoagulant medications were discontinued before surgery in all cases, they were restarted 1 week after the surgery, depending on the patient’s condition and comorbidities.

Outcome measures

Neurological outcomes represented by GCS and modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores at discharge, procedure-related complications, and the recurrence of the hematoma were analyzed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the proposed procedure.

RESULTS

The results are summarized in

Illustrative cases

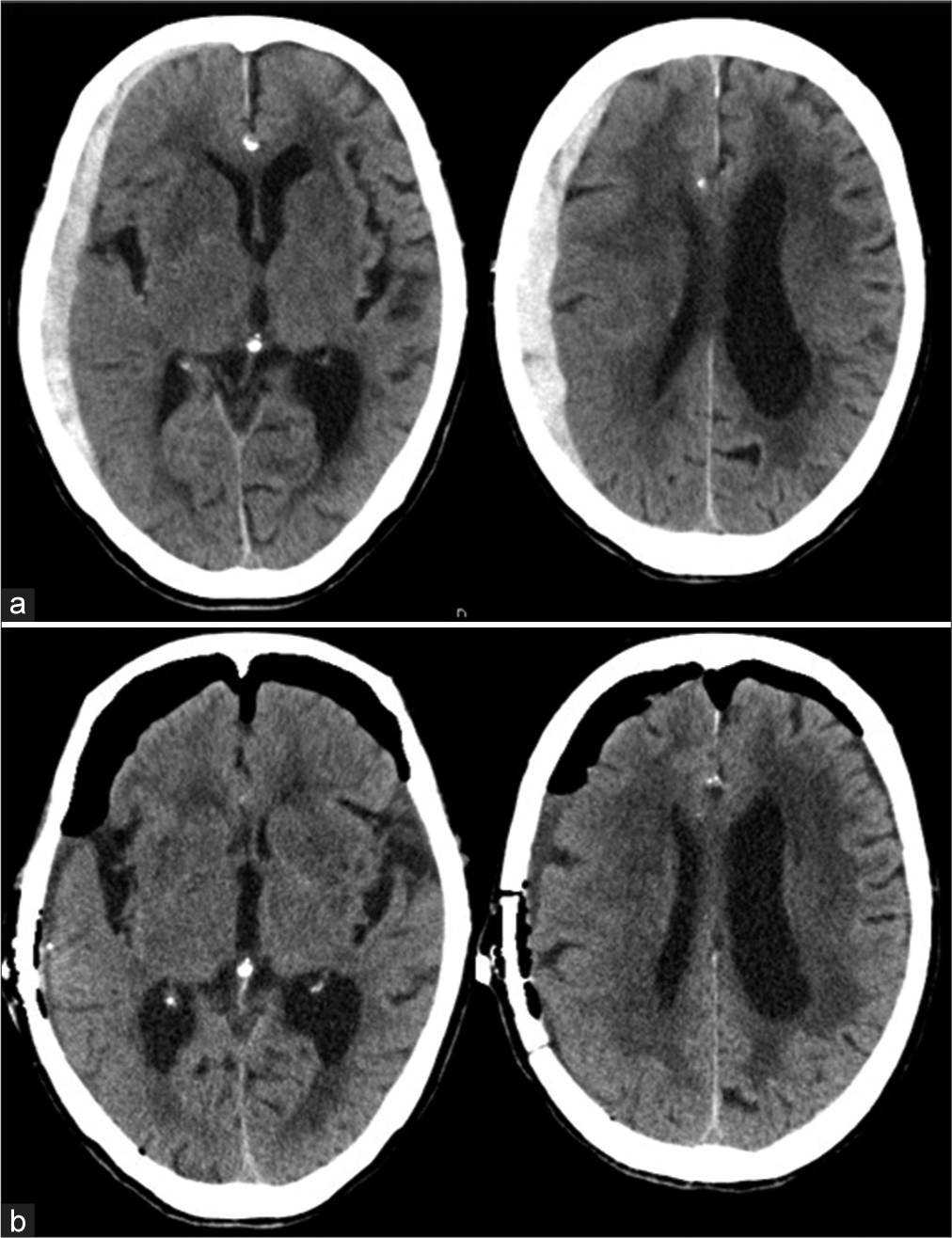

A 93-year-old female presented to our hospital with vomiting, aphasia, and left hemiparesis after a fall at home. On admission, the patient’s level of consciousness was E1V1M5 on the GCS. Initial head CT revealed a right ASDH without contusion or another intracranial hematoma. The ASDH was approximately 1-cm thick [

DISCUSSION

Surgical evacuation of ASDH in the elderly remains a point of contention because of the significant associated mortality. There have been increasing reports of the use of endoscopic hematoma evacuation for ASDH in the elderly.[

The reported craniotomy size ranged between 2 and 5 cm in diameter.[

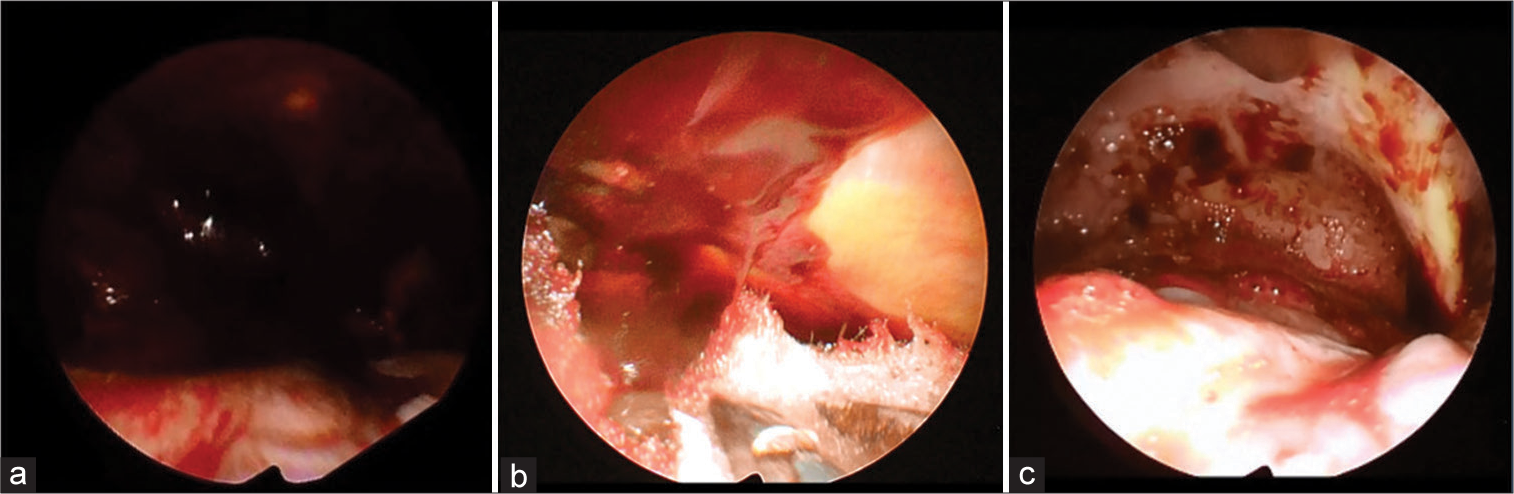

Another important consideration is the improved visualization of the subdural space. Hematomas are black; therefore, they absorb light. Therefore, the visibility of the subdural space becomes poor under an endoscope. We improved the visibility of the subdural space by covering the brain surface with a white protective sheet, which reflects light.

In this case series, all surgical procedures were performed under general anesthesia. The primary initial treatment of severe trauma is to secure the airway and stabilize respiratory and circulatory conditions. Endotracheal intubation was initiated in the emergency department for eight of nine patients with severe (GCS score ≤8) ASDH. The option of performing endoscopic hematoma evacuation under local anesthesia is one of its major advantages, as this provides a surgical alternative for patients who cannot tolerate general anesthesia. Suitability for local anesthesia implies that the patient can maintain their airway. Another consideration is the risk of excessive patient movement intraoperatively following ASDH evacuation, which may necessitate sedation or conversion to general anesthesia. Essentially, a sufficiently experienced neuroanesthetist must be immediately available to consider sedation or conversion to general anesthesia.

The median operative duration was reported to vary between 65 and 111 min.[

Therefore, it is thought that endoscopic surgery is useful for ASDH.

Kiyohira et al. suggest the value of burr hole surgery, followed by ICP monitoring, in patients with ASDH.[

However, this case series involved a small number of patients and was a retrospective study. Thus, conducting a study that involves more cases and examines long-term outcomes will be necessary.

CONCLUSION

Endoscopic hematoma evacuation of ASDH and postoperative management using an ICP sensor for appropriately selected patients are a safe and effective approach. We believe that this technique may be a less invasive surgical approach for treating patients with ASDH.

Declaration of patient consent

Patients’ consent not required as patients’ identities were not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Codd PJ, Venteicher AS, Agarwalla PK, Kahle KT, Jho DH. Endoscopic burr hole evacuation of an acute subdural hematoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2013. 20: 1751-3

2. Hwang SC, Shin DS. Endoscopic treatment of acute subdural hematoma with a normal small craniotomy. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2020. 81: 10-6

3. Ichimura S, Takahara K, Nakaya M, Yoshida K, Mochizuki Y, Fukuchi M. Neuroendoscopic hematoma removal with a small craniotomy for acute subdural hematoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2019. 61: 311-4

4. Katsuki M, Kakizawa Y, Nishikawa A, Kunitoki K, Yamamoto Y, Wada N. Fifteen cases of endoscopic treatment of acute subdural hematoma with small craniotomy under local anesthesia: Endoscopic hematoma removal reduces the intraoperative bleeding amount and the operative time compared with craniotomy in patients aged 70 or older. Neurol Med Chir. 2020. 60: 439-49

5. Kawasaki T, Kurosaki Y, Fukuda H, Kinosada M, Ishibashi R, Handa A. Flexible endoscopically assisted evacuation of acute and subacute subdural hematoma through a small craniotomy: Preliminary results. Acta Neurochir. 2018. 160: 241-8

6. Kiyohira M, Suehiro E, Shinoyama M, Fujiyama Y, Haji K, Suzuki M. Combined strategy of burr hole surgery and elective craniotomy under intracranial pressure monitoring for severe acute subdural hematoma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2021. 61: 253-9

7. Kon H, Saito A, Uchida H, Inoue M, Sasaki T, Nishijima M. Endoscopic surgery for traumatic acute subdural hematoma. Case Rep Neurol. 2013. 5: 208-13

8. Kuge A, Rei K, Mitobe Y, Yamaki T, Sato S, Saito S. Delayed acute subdural hematoma treated with endoscopic procedure: A case report. Surg Neurol Int. 2020. 11: 350

9. Maruya J, Tamura S, Hasegawa R, Saito A, Nishimaki K, Fujii Y. Endoscopic hematoma evacuation following emergent burr hole surgery for acute subdural hematoma in critical conditions: Technical note. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2018. 12: 48-51

10. Matsumoto H, Minami H, Hanayama H, Yoshida Y. Endoscopic hematoma evacuation for acute subdural hematoma in the elderly: A preliminary study. Surg Innov. 2018. 25: 455-64

11. Miki K, Nonaka M, Kobayashi H, Horio Y, Abe H, Morishita T. Optimal surgical indications of endoscopic surgery for traumatic acute subdural hematoma in elderly patients based on a single-institution experience. Neurosurg Rev. 2021. 44: 1635-43

12. Rienzo AD, Iacoangeli M, Alvaro L, Colasanti R, Somma L, Nocchi N. Mini-craniotomy under local anesthesia to treat acute subdural hematoma in deteriorating elderly patients. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2017. 78: 535-40

13. Spencer RJ, Manivannan S, Zaben M. Endoscope-assisted techniques for evacuation of acute subdural haematoma in the elderly: The lesser of two evils? A scoping review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2021. 207: 106712

14. Tamura R, Kuroshima Y, Nakamura Y. Neuroendoscopic removal of acute subdural hematoma with contusion: Advantages for elderly patients. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2016. 2016: 2056190

15. Yokosuka K, Uno M, Matsumura K, Takai H, Hagino H, Matsushita N. Endoscopic hematoma evacuation for acute and subacute subdural hematoma in elderly patients. J Neurosurg. 2015. 123: 1065-9

Prof. Dr. KDM Resch

Posted January 17, 2023, 9:34 am

MIN in neurosurgery is not indicated in old patients alone, it is defined by medical ethics and pathophysiology!

Each patient has the right to benefit from MIN (like endoscopic techniques). So it should be rather a gould-standard than an elective strategy.

The secret of MIN is individual indication and ergonomics in MIN.

Ref.: Resch KDM ; Key concepts in MIN Vol. I+II/ Springer 2021/22