- Department of Tropical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt

- Department of Infection Control, Ibn Sina Hospital, Al-Sabah Medical Area, Kuwait

- Department of ENT, Zain Hospital, Al-Sabah Medical Area, Kuwait City, Kuwait

- Department of Neurosurgery, Ibn Sina Hospital, Al-Sabah Medical Area, Kuwait City, Kuwait

Correspondence Address:

Waleed A. Azab, Department of Neurosurgery, Ibn Sina Hospital, Al-Sabah Medical Area, Kuwait City, Kuwait.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_849_2024

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Marwa Ibrahim1,2, Marwan Alqunaee3, Mustafa Najibullah4, Zafdam Shabbir4, Waleed A. Azab4. Isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucoceles: A rare entity with a high propensity for causing neurological complications. 29-Nov-2024;15:444

How to cite this URL: Marwa Ibrahim1,2, Marwan Alqunaee3, Mustafa Najibullah4, Zafdam Shabbir4, Waleed A. Azab4. Isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucoceles: A rare entity with a high propensity for causing neurological complications. 29-Nov-2024;15:444. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=13254

Abstract

Background: Isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucoceles are extremely rare and potentially associated with visual disturbances, cranial nerve (CN) deficits, or pituitary dysfunction. Their initial symptoms are often absent or nonspecific, and routine examination offers little information, resulting in diagnostic and therapeutic delays. A high index of suspicion and a thorough understanding of their clinical presentation, neuroradiological features, microbiological implications, and complication profile are crucial for early diagnosis and prompt management. We, herein, analyze a series of consecutive cases of isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucoceles whom we treated, add to the currently existing published cases, and review the pertinent literature.

Methods: From the databases of endoscopic endonasal skull base and rhinological surgical procedures maintained by our groups, all cases with isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucoceles were retrieved and included in the study. Clinical and radiological findings, histopathologic evidence of fungal rhinosinusitis, culture results, clinicopathological designation, treatment details, and outcome of CN neuropathies were analyzed.

Results: Headache was the most common symptom (seven cases). Oculomotor (three cases) and abducens (two cases) nerve palsies were encountered in five out of eight patients. Visual loss was seen in two cases. Hypopituitarism was seen in one case. All patients underwent endoscopic endonasal wide bilateral sphenoidectomy. CN palsies improved in four out of five cases.

Conclusion: Endoscopic endonasal wide sphenoidectomy is the surgical treatment of choice and should be performed in a timely manner to prevent permanent sequelae. Histopathological and microbiological examination findings should both be obtained as they dictate the next steps of therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Endoscopic, Fungus ball, Rhinosinusitis, Transsphenoidal, Visual

INTRODUCTION

Isolated sphenoid sinus mucoceles are relatively uncommon and represent 1–2% of all paranasal sinus mucoceles.[

The initial symptoms of these lesions are often absent or nonspecific, and routine examination offers little information, resulting in diagnostic and therapeutic delays.[

In one recently published large study of radiologically identified isolated sphenoid sinus opacifications, it was demonstrated that clinicians generally underestimated the risks of sphenoid sinus disease.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From the databases of the endoscopic endonasal skull base and rhinological surgical procedures maintained by our groups since the year 2015, all cases with isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucoceles were retrieved and included. Cases of isolated sphenoid sinus bacterial mucoceles were excluded from the study. Medical charts, diagnostic imaging findings, histopathology and microbiology results, and operative notes and videos were retrospectively reviewed.

For all patients, demographic data, duration of mucocele-related symptoms, clinical findings, histopathologic evidence of FRS, fungal culture results, clinicopathological designation, surgical and medical treatment details, and clinical outcome of CN neuropathies were analyzed.

Two forms of fungal sinonasal infection that may result in sphenoid sinus mucocele formation include fungus ball (FB) and allergic FRS (AFRS). FB is an extra-mucosal mycotic proliferation that completely or partially fills a paranasal sinus and is usually associated with minimal mucosal inflammation.[

All cases of FB were diagnosed according to deShazo et al. criteria,[

RESULTS

Demographics and clinical findings

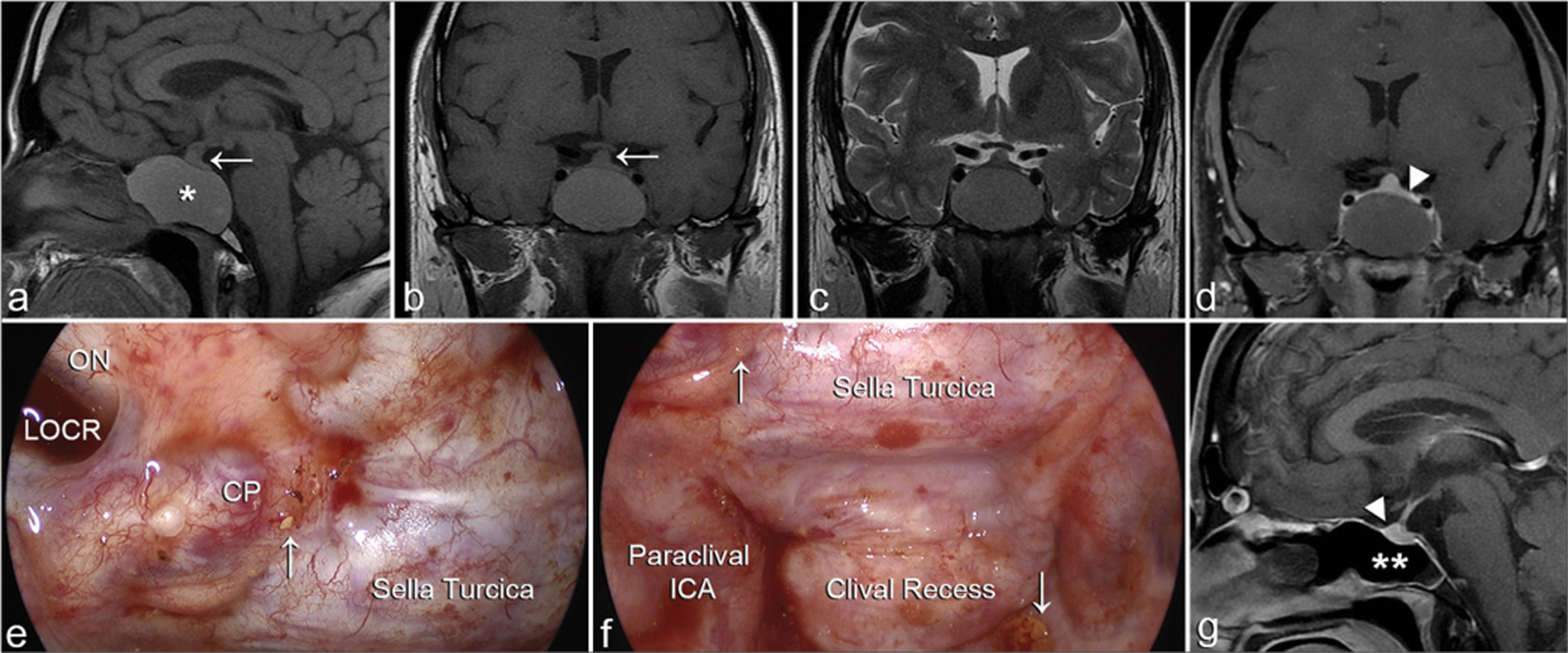

Eight patients with a diagnosis of isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucoceles were retrieved and included in the analysis. The patient population consisted of five males and three females, with an age range between 26 and 73 years (Mean age 47.6). The duration of mucocele-related symptoms ranged between 4 and 24 months. CN palsies included oculomotor nerve palsy observed in three cases and abducens nerve palsy observed in two cases. Visual loss was seen in two cases. Headache was the most common symptom and was present in seven cases. FB was diagnosed in three patients and AFRS in four patients. CN palsies improved in four out of five cases. Hypopituitarism manifesting as central hypothyroidism (low levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH], T4) and low adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and serum cortisol levels were seen in one case.

Neuroradiological investigations

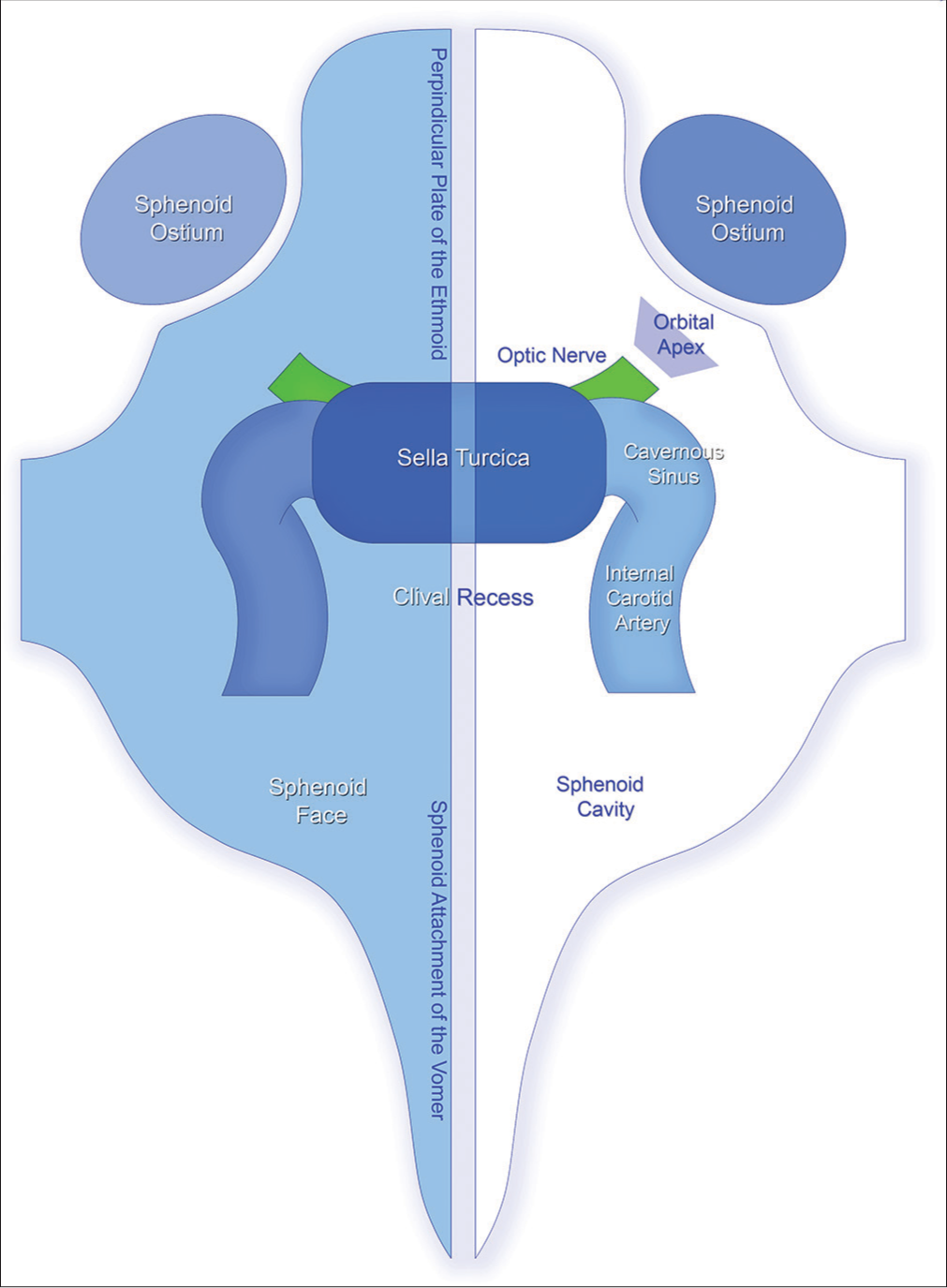

All patients had radiological findings consistent with isolated mucocele formation within the sphenoid sinus. Computed tomography (CT) scans revealed opacification and expansion of the sphenoid sinus, with variable degrees of bone erosion in all cases. Compression of the ethmoid sinuses, anterior cranial base, sellar floor, medial orbital wall, or orbital apex was also seen in some cases. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) further demonstrated an iso- to slightly hyper-intense signal of the fluid content and a hypointense signal of the fungal balls. Areas of mixed signal intensity where small foci of T2 hyperintensities are detected within an otherwise uniform T1 isointense signal were seen in 2 cases. No enhancement of the mucoceles was seen after contrast injection. Peripheral enhancement was seen in three cases and corresponded to the contrast uptake by the mucosa of the sinus.

Treatment modalities

All patients underwent endoscopic endonasal wide bilateral sphenoidectomy. Dexamethasone was administered only to patients with neurological deficits and tapered down over 2 weeks postoperatively. Fungal cultures were performed in three out of the eight patients included and were positive in only one patient in whom Aspergillus fumigatus was isolated.

Outcome

Visual loss improved in all patients after surgery. Except in one patient with abducens nerve palsy, all CN palsies recovered within a maximum of 6 weeks postoperatively.

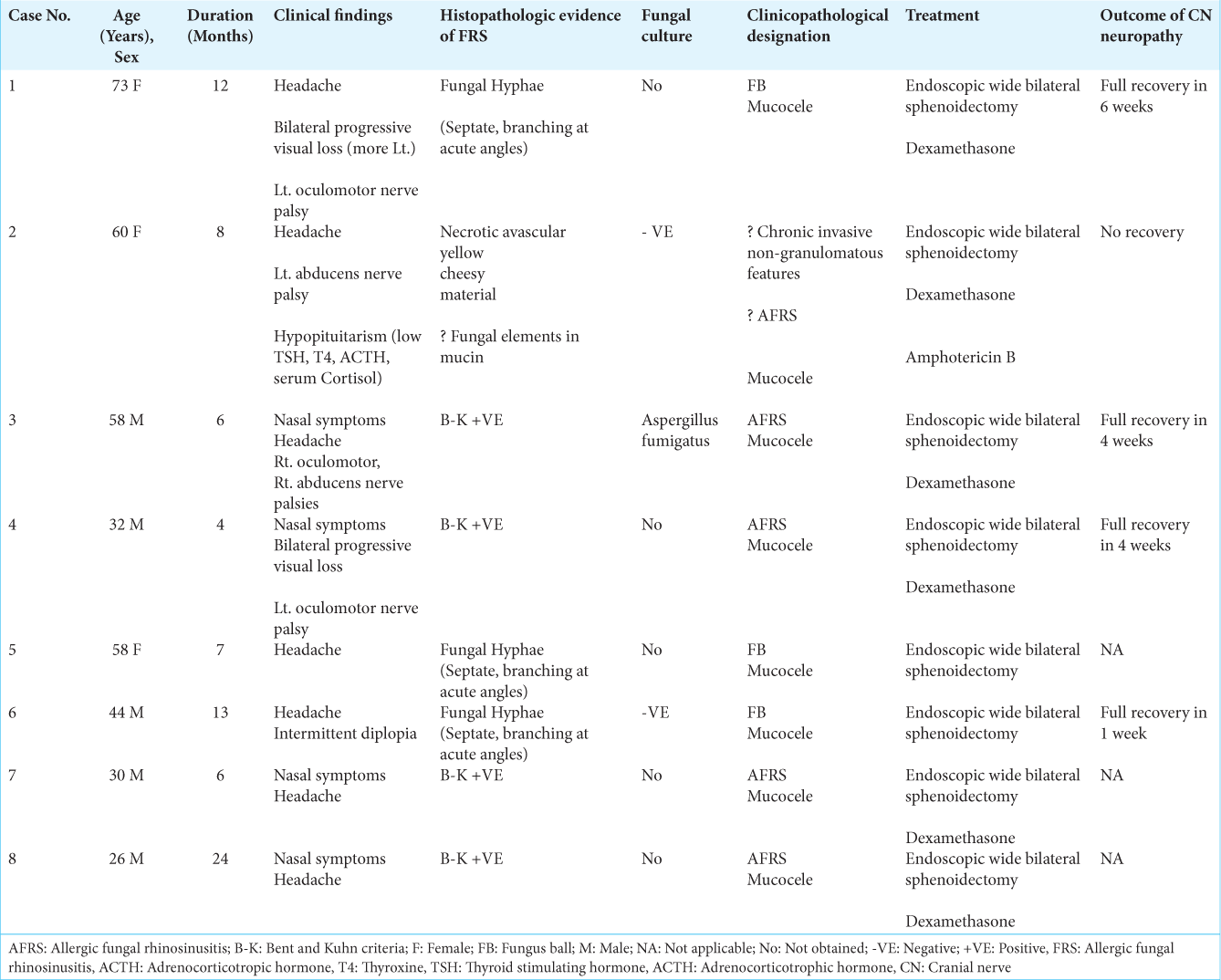

Figure 2:

Isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucocele (Case No. 4). (a-d) Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reveals an expansile sphenoid sinus mass (an asterisk) that displays a slightly hyperintense signal on T1-weighted (a and b), and (c) an isointense signal on T2-weighted MRI. (d) No enhancement is seen after contrast injection. Compression of the pituitary gland (a and b arrows, d arrowhead) is notable due to the mass effect of the mucocele. (e-f) Intraoperative views during mucocele marsupialization and drainage through an endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal sphenoidectomy. Anatomical landmarks within the sphenoid sinus are seen. Yellow tiny fungal material is seen attached to the walls (arrows). (g) Postoperative sagittal T1-weighted MRI with contrast demonstrating full decompression of the mucocele and evacuation of its contents (double asterisks). The decompressed pituitary gland is seen (arrowhead). CP: Carotid prominence, LOCR: Lateral optico-carotid recess, ON: Optic nerve.

DISCUSSION

Clinical features of isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucoceles

At the early stages of their development, sphenoid sinus mucoceles are often asymptomatic.[

In addition to the sinonasal symptomatology associated with chronic FRS, the specific clinical findings reported in patients with isolated sphenoid fungal mucoceles include headache, blurring of vision, variable degrees of unilateral or bilateral visual loss, optic disc pallor, retro-orbital pain, diplopia, and abducens nerve palsy,[

Although oculomotor nerve palsy is well documented in cases of sphenoid mucoceles of non-fungal etiology,[

Extrapolating from the literature on isolated sphenoid mucocele of non-fungal etiology, oculomotor nerve involvement has been reported to represent around 70% of ocular palsies and is more frequent than trochlear and abducent nerve palsies,[

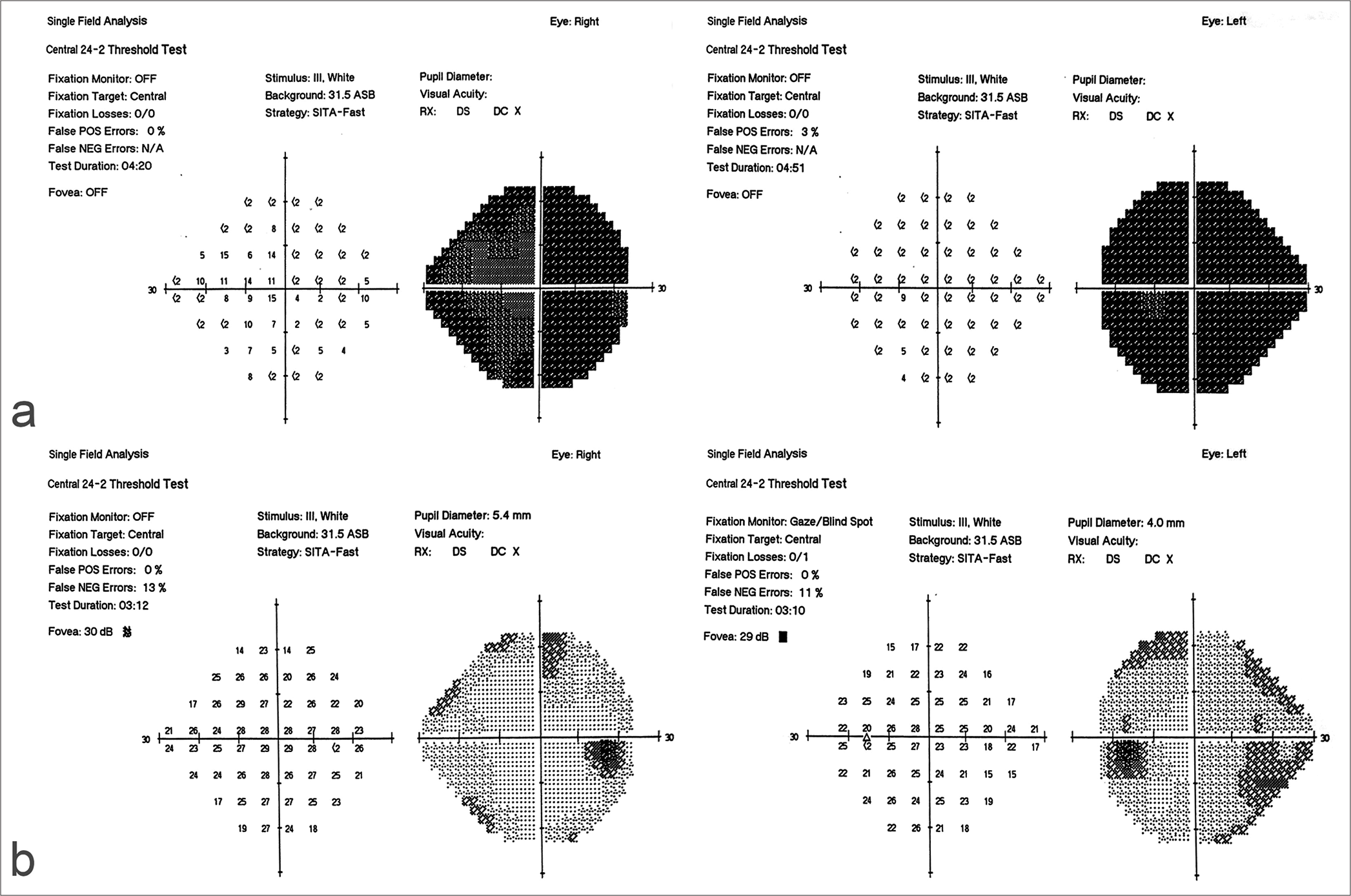

Visual loss was observed in two of our eight cases and was progressive in course [

In our series, seven out of eight patients complained of headaches that almost spanned the whole duration of the clinical history, findings that are similar to those in other reported cases.[

We encountered one case of hypopituitarism (Case No. 2) in our series. Hormonal profile evaluation revealed low levels of TSH, T4, ACTH, and serum cortisol. Extensive invasion of the clivus, sellar floor, sellar dura, and pituitary gland was evident during surgery, with features of chronic nongranulomatous inflammation seen on histopathological examination. We speculate that mixed features of AFRS and chronic non-granulomatous FRS did concomitantly exist in this patient [

Figure 4:

Neuroimaging findings in Case No. 2. (a-c) Preoperative computed tomography scans revealed extensive bone erosion, including the clivus (a single arrow), sellar floor (an asterisk), sphenoid sinus floor (a double arrows), and left petrous apex (c, arrow). (d-h) Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (d-h) revealed a T1-weighted isointense expansile lesion filling the sphenoid sinus cavity and the sella turcica (d, asterisk). The lesion was seen to have almost completely eroded and replaced the clivus. Very faint marginal enhancement is seen post-gadolinium injection. (e) No enhancement of the lesion was present. (f-g) On T2-weighted images, the lesion displayed mixed iso- and hyper-intense signals. Mucus within the remaining small cavity of the sphenoid sinus (f, arrow) and (h) compressed pituitary stalk (h, arrow) are observed. Postoperative contrast-enhanced (i) sagittal, (j) coronal, and (k-l) consecutive axial T1-weighted MRI demonstrated a gross total resection. The normal pituitary tissue is seen (i, arrow).

Figure 5:

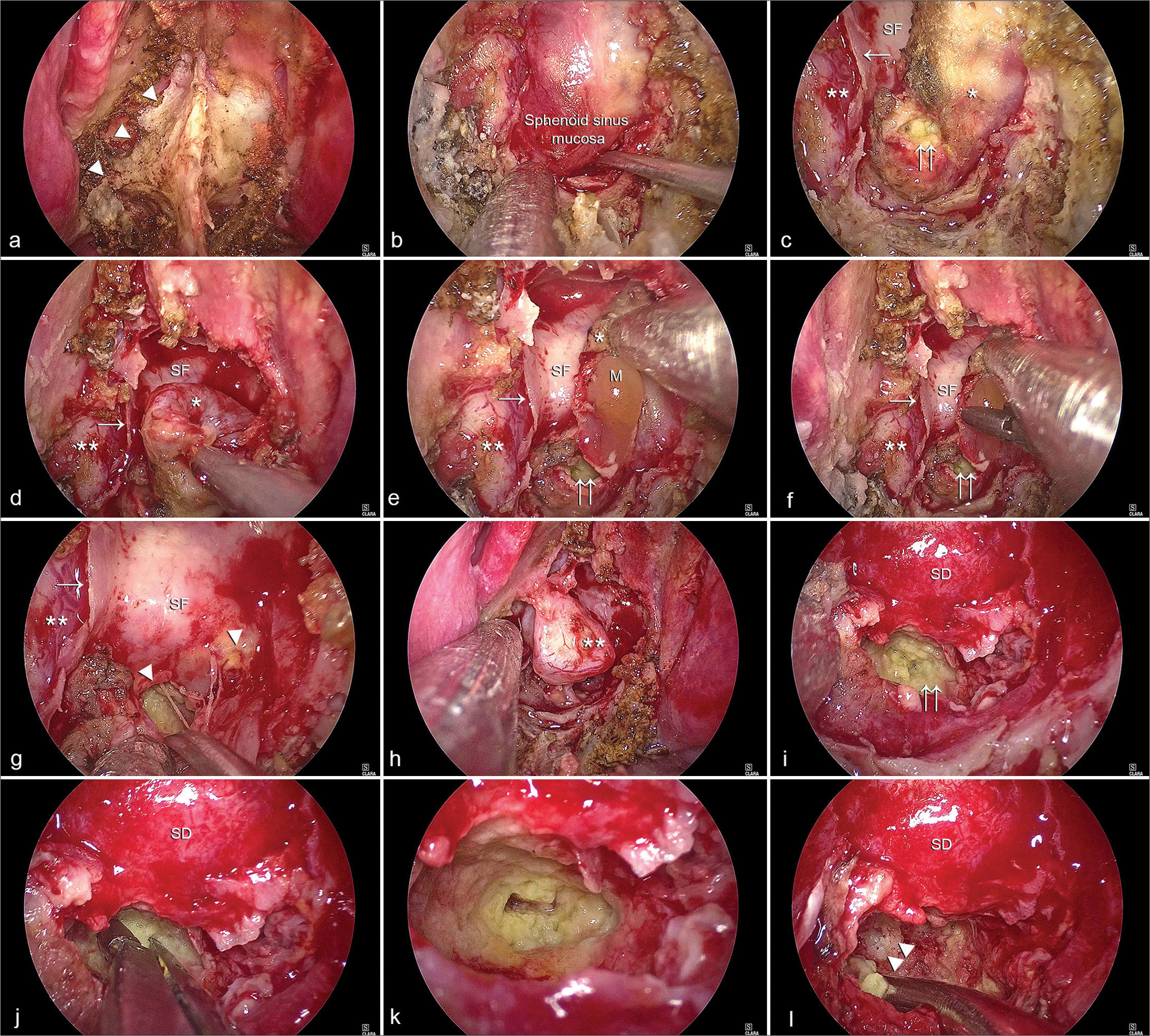

Step-wise intraoperative views during mucocele resection through an endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal sphenoidectomy, Case No. 2. (a) Erosion of bone of the right side of the sphenoid face was noted at the beginning of the sphenoid phase of the procedure (a, arrowheads). (b) After wide sphenoidectomy, yellow discoloration of the sphenoid sinus mucosa was observed. In (c), the mucosa of the left half of the sinus (asterisk) was then coagulated and shrunk down where a clear view of the sphenoid septum (arrow), the bony sellar face (SF), and the mucosa of the right half of the sinus (double asterisks) was obtained. Yellow cheesy material (double arrows) is seen through a small rent in the left sphenoid mucosa. (d) Removal of the left sinus mucosal lining is performed. (e) Mucus content (M) is seen in (e) and (f) biopsied. (g) As the mucosal envelope of the left half of the sinus is completely removed, clear bone erosion and invasion of the sellar floor are observed (g, arrowheads). (h) The right sphenoid mucosa is then removed. In (i), the bony SF has been removed, the sellar dura is exposed, and intrasellar invasion is seen. (j) The invasive yellow material is biopsied, and (k) its superior extension within the sella is seen using a 45° endoscope in a close-up view. (l) As removal of the invasive material continues, bone erosion of the clivus and petrous apex (double arrowheads) is appreciated. Asterisk: Mucosa of the left half of the sphenoid sinus, Single arrow: Sphenoid septum, SF: bony sellar face, Double asterisks: Mucosa of the right half of the sphenoid sinus, Double arrows: Invasive cheesy content of the mucocele

Figure 6:

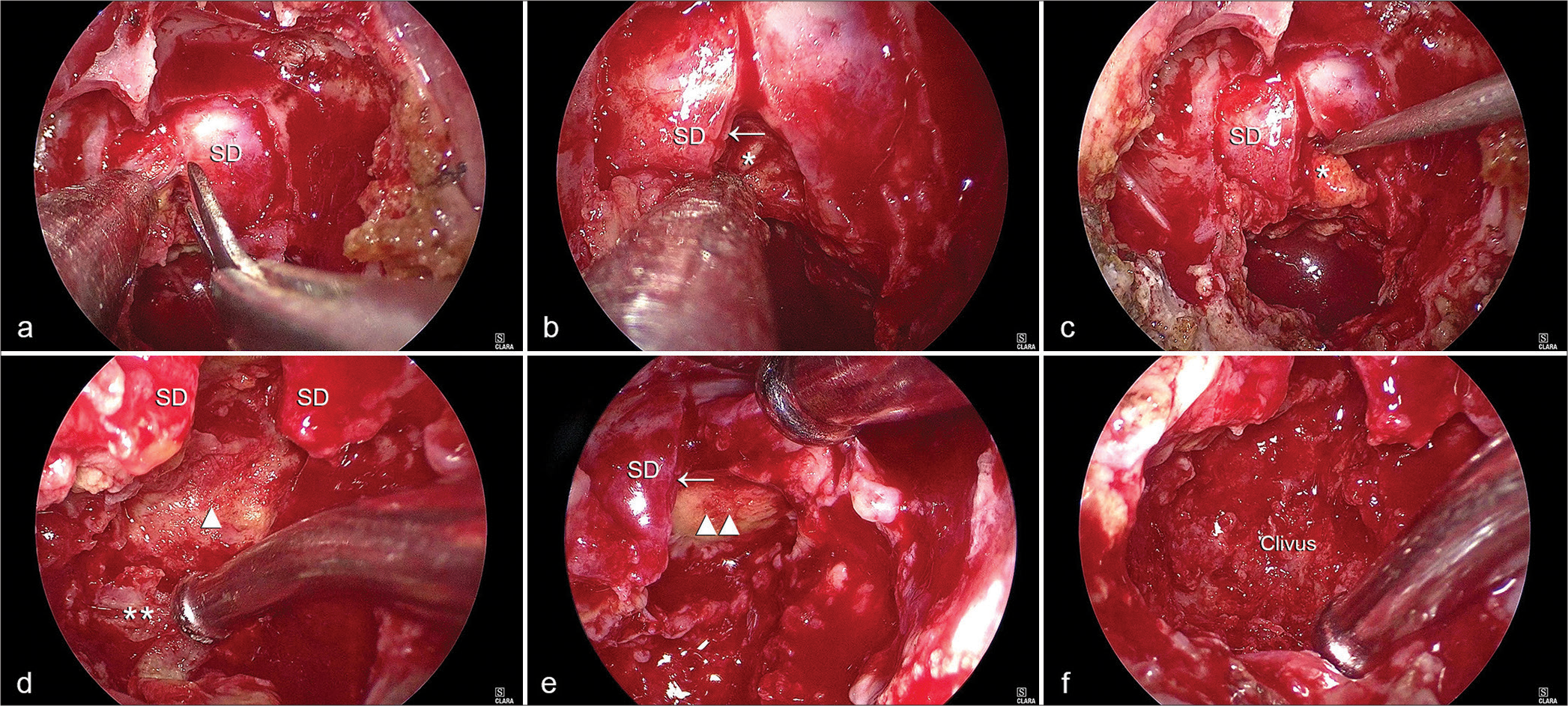

Intraoperative views during the intrasellar resection in Case No. 2. (a) Incision of the sellar dura is performed. (b) The normal pituitary (arrow) is seen compressed underneath the dura. The invasive material (asterisk) is seen filling the sellar cavity. (c) A pituitary ring curette is used to remove the invasive material (asterisk) from within the sella. (d) The yellow invasive material was adherent to the posterior wall of the sella (d, arrowhead) and (e) the descending cistern at the superior part of the sella, Arrow: SD (e, double arrows heads). Eroded petrous apex (d, double asterisks) is also observed. (f) A full view of the eroded clival bone within the clival recess is obtained. Single arrow: Pituitary gland, SD: Sellar dura.

Neuroradiology of isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucoceles

Neuroimaging is essential to disclose the pathoanatomical details of isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucoceles. CT reveals sinus opacification and sinus bony wall expansion and erosion, and MRI provides details of the signal intensities of the mucocele contents and involvement of the optic nerve, optic chiasm, pituitary gland, and cavernous sinus.[

T2-weighted MRIs are particularly important to differentiate between the hypointense fungal elements and the hyperintense signal of mucosal swelling or low-protein mucous retention.[

FRS and mucocele formation

Fungal infections of the paranasal sinuses represent a disease spectrum ranging from colonization to invasive rhinosinusitis.[

FRS is broadly classified as either non-invasive or invasive. Non-invasive sinonasal fungal diseases include saprophytic fungal infestation (SFI), FB, and AFRS. The invasive forms of FRS include acute invasive FRS, chronic invasive FRS, and chronic granulomatous invasive FRS.[

SFI is traditionally described as fungal colonization of the secretions of the sinonasal cavity or crusted mucosa, mostly in patients with a history of previous sinus surgery. It is the least common form of FRS described in the literature and is thought to precede the development of an FB.[

FB is an extra-mucosal mycotic proliferation that completely or partially fills a paranasal sinus and is usually associated with minimal mucosal inflammation.[

AFRS is diagnosed according to the original Bent and Khun criteria.[

The pathogenesis of AFRS is not yet fully understood. Although previously considered a type I hypersensitivity reaction to fungi, the condition is currently believed to represent a host reaction to fungal proteins.[

Although isolated sphenoid fungal mucoceles have been exclusively reported in patients with non-invasive FRS, in one of our patients (Case No. 2), necrotic avascular yellow cheesy material was intraoperatively seen to invade the dura mater, clival bone, petrous apex, sella turcica, and pituitary gland. Fungal elements were suspected on histopathological examination of the associated mucus within the sphenoid sinus. The patient had a past medical history of bronchial asthma. Nasal polyps were seen during surgery. In our opinion, mixed features of AFRS and chronic non-granulomatous FRS probably exist in this patient. It is important to note that non-invasive and invasive forms of FRS have been reported not to be distinct necessarily and may coexist in the same individual.[

The pathophysiological process of mucocele formation in cases of FRS is yet to be fully elucidated.[

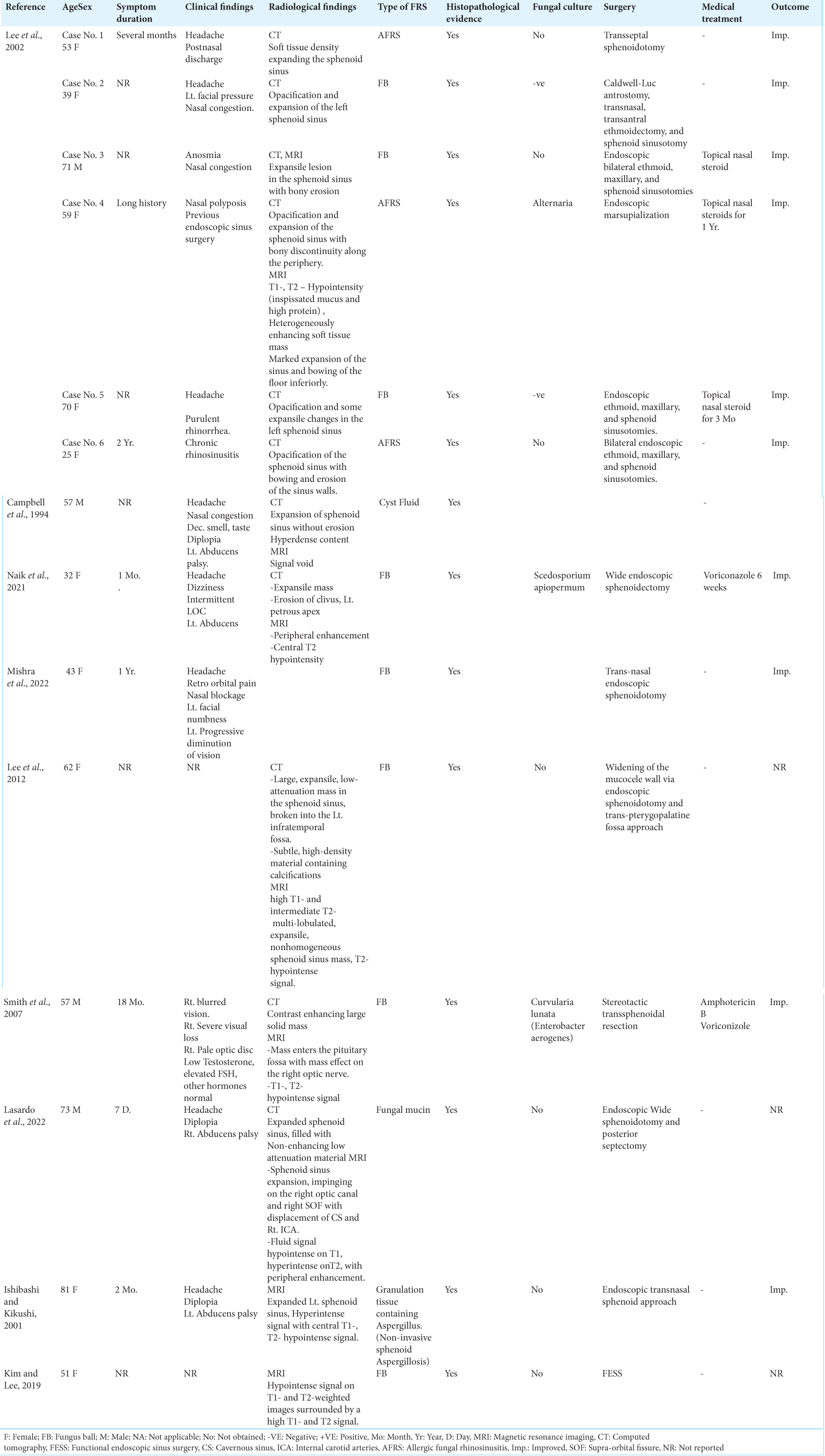

As it pertains to the microbiological profile in isolated sphenoid fungal mucocele cases, Aspergillus is by far the most common organism.[

Microbiological diagnosis of isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucocele

In common practice, fungal cultures are frequently not obtained due to the large body of literature establishing fungi of Aspergillus species as the most common causative microorganisms of FRS.[

Treatment of isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucoceles

The current consensus is to treat sphenoid sinus mucoceles surgically.[

All patients in our series underwent endoscopic endonasal wide bilateral sphenoidectomy with marsupialization of the mucocele and clearance of its contents. Removal of the anterior and inferior walls of the sphenoid sinus is also undertaken. Many other groups have adopted this surgical philosophy, and it has now emerged as the standard treatment of choice.[

As FBs are not invasive, systemic or topical antifungal therapy is not indicated.[

Limitations of the study

The limitations of our study include its retrospective nature, small number of patients, and unavailability of the specific causative fungus in the majority of patients. Larger scale prospective multicenter collaborative studies are clearly needed and should involve neurosurgeons, rhinologists, and infectious disease specialists.

CONCLUSION

Isolated sphenoid sinus fungal mucoceles are very rare and may be associated with serious and permanent neurological deficits. Advanced imaging studies provide appropriate clinical diagnosis. Histopathological and microbiological examination findings should both be obtained as they dictate the next steps of therapeutic intervention. Endoscopic endonasal wide sphenoidectomy is the surgical treatment of choice and should be performed in a timely manner to prevent permanent sequelae. A more widespread knowledge diffusion on this entity is required, and large-scale prospective multicenter collaborative studies are needed and should involve neurosurgeons, rhinologists, and infectious disease specialists.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required because the study is retrospective and all patient details were anonymized.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Akan H, Cihan B, Celenk C. Sphenoid sinus mucocele causing third nerve paralysis: CT and MR findings. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004. 33: 342-4

2. Akdis CA, Bachert C, Cingi C, Dykewicz MS, Hellings PW, Naclerio RM. Endotypes and phenotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis: A PRACTALL document of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013. 131: 1479-90

3. Ashida N, Maeda Y, Kitamura T, Hayama M, Tsuda T, Nakatani A. Isolated sphenoid sinus opacification is often asymptomatic and is not referred for otolaryngology consultation. Sci Rep. 2021. 11: 11902

4. Bachert C, Akdis CA. Phenotypes and emerging endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016. 4: 621-8

5. Bent JP, Kuhn FA. Diagnosis of allergic fungal sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994. 111: 580-8

6. Cakmak O, Shohet MR, Kern EB. Isolated sphenoid sinus lesions. Am J Rhinol. 2000. 14: 13-9

7. Campbell RE, Barone CA, Makris AN, Miller DA, Mohuchy T, Putnam SG. Image interpretation session: 1993. Fungal mucocele (aspergillosis) of the sphenoid sinus. Radiographics. 1994. 14: 197-9

8. Chakrabarti A, Denning DW, Ferguson BJ, Ponikau J, Buzina W, Kita H. Fungal rhinosinusitis: A categorization and definitional schema addressing current controversies. Laryngoscope. 2009. 119: 1809-18

9. Chakrabarti A, Kaur H. Allergic Aspergillus rhinosinusitis. J Fungi (Basel). 2016. 2: 32

10. Chapurin N, Wang C, Steinberg DM, Jang DW. Hyperprolactinemia secondary to allergic fungal sinusitis compressing the pituitary gland. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2016. 2016: 7260707

11. Charakorn N, Snidvongs K. Chronic sphenoid rhinosinusitis: Management challenge. J Asthma Allergy. 2016. 9: 199-205

12. Chen L, Jiang L, Yang B, Subramanian PS. Clinical features of visual disturbances secondary to isolated sphenoid sinus inflammatory diseases. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017. 17: 237

13. Chobillon MA, Jankowski R. Relationship between mucoceles, nasal polyposis and nasalisation. Rhinology. 2004. 42: 219-24

14. Cody DT, Neel HB, Ferreiro JA, Roberts GD. Allergic fungal sinusitis: The Mayo Clinic experience. Laryngoscope. 1994. 104: 1074-9

15. Das A, Bal A, Chakrabarti A, Panda N, Joshi K. Spectrum of fungal rhinosinusitis; histopathologist’s perspective. Histopathology. 2009. 54: 854-9

16. deShazo RD, O’Brien M, Chapin K, Soto-Aguilar M, Swain R, Lyons M. Criteria for the diagnosis of sinus mycetoma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997. 99: 475-85

17. Deutsch PG, Whittaker J, Prasad S. Invasive and non-invasive fungal rhinosinusitis-a review and update of the evidence. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019. 55: 319

18. Dykewicz MS, Rodrigues JM, Slavin RG. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018. 142: 341-51

19. Eggesbø HB. Radiological imaging of inflammatory lesions in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Eur Radiol. 2006. 16: 872-88

20. Ferguson BJ. Fungus balls of the paranasal sinuses. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2000. 33: 389-98

21. Ferreiro JA, Carlson BA, Cody DT. Paranasal sinus fungus balls. Head Neck. 1997. 19: 481-6

22. Friedmann G, Harrison S. Mucocoele of the sphenoidal sinus as a cause of recurrent oculomotor nerve palsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1970. 33: 172-9

23. Friedman A, Batra PS, Fakhri S, Citardi MJ, Lanza DC. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: Etiology and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005. 133: 544-50

24. Gan EC, Thamboo A, Rudmik L, Hwang PH, Ferguson BJ, Javer AR. Medical management of allergic fungal rhinosinusitis following endoscopic sinus surgery: An evidence-based review and recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014. 4: 702-15

25. Gao X, Li B, Ba M, Yao W, Sun C, Sun X. Headache secondary to isolated sphenoid sinus fungus ball: Retrospective analysis of 6 cases first diagnosed in the neurology department. Front Neurol. 2018. 9: 745

26. Granville L, Chirala M, Cernoch P, Ostrowski M, Truong LD. Fungal sinusitis: Histologic spectrum and correlation with culture. Hum Pathol. 2004. 35: 474-81

27. Giovannetti F, Filiaci F, Ramieri V, Ungari C. Isolated sphenoid sinus mucocele: Etiology and management. J Craniofac Surg. 2008. 19: 1381-4

28. Glass D, Amedee RG. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis: A review. Ochsner J. 2011. 11: 271-5

29. Grosjean P, Weber R. Fungus balls of the paranasal sinuses: A review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007. 264: 461-70

30. Hejazi N, Witzmann A, Hassler W. Ocular manifestations of sphenoid mucoceles: Clinical features and neurosurgical management of three cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2001. 56: 338-43

31. Hoxworth JM, Glastonbury CM. Orbital and intracranial complications of acute sinusitis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2010. 20: 511-26

32. Ishibashi T, Kikuchi S. Mucocele-like lesions of the sphenoid sinus with hypointense foci on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroradiology. 2001. 43: 1108-11

33. Jacobson DM. Pupil involvement in patients with diabetes-associated oculomotor nerve palsy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998. 116: 723-7

34. Kim JS, Lee EJ. Endoscopic findings of fungal ball in the mucocele after endonasal transsphenoidal surgery. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021. 100: P169-70

35. Klapper SR, Lee AG, Patrinely JR, Stewart M, Alford EL. Orbital involvement in allergic fungal sinusitis. Ophthalmology. 1997. 104: 2094-100

36. Klossek JM, Serrano E, Péloquin L, Percodani J, Fontanel JP, Pessey JJ. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery and 109 mycetomas of paranasal sinuses. Laryngoscope. 1997. 107: 112-7

37. Knisely A, Holmes T, Barham H, Sacks R, Harvey R. Isolated sphenoid sinus opacification: A systematic review. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017. 38: 237-43

38. Kösling S, Hintner M, Brandt S, Schulz T, Bloching M. Mucoceles of the sphenoid sinus. Eur J Radiol. 2004. 51: 1-5

39. Kokoszka M, Stryjewska-Makuch G, Kantczak A, Górny D, Glück J. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis in Europe: Literature review and own experience. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2023. 184: 856-65

40. Lasrado S, Moras K, Jacob C. A rare case of sphenoid sinus mucocele presenting with lateral rectus palsy. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022. 74: 1396-8

41. Lee JT, Bhuta S, Lufkin R, Calcaterra TC. Fungal mucoceles of the sphenoid sinus. Laryngoscope. 2002. 112: 779-83

42. Lee DH, Kim SK, Joo YE, Lim SC. Fungus ball within a mucocele of the sphenoid sinus and infratemporal fossa: Case report with radiological findings. J Laryngol Otol. 2012. 126: 210-3

43. Li W, Huang J, Yang L, Chang L, Zhang G. Mucocele of the sphenoid sinus as a rare cause of isolated oculomotor nerve palsy: Case report and review of the literature. Clin Surg. 2016. 1: 1207

44. Lim CC, Dillon WP, McDermott MW. Mucocele involving the anterior clinoid process: MR and CT findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999. 20: 287-90

45. Marple BF. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis: Surgical management. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2000. 33: 409-19

46. Miglets AW, Saunders WH, Ayers L. Aspergillosis of the sphenoid sinus. Arch Otolaryngol. 1978. 104: 47-50

47. Mishra A, Patel D, Munjal VR, Patidar M. Isolated sphenoid sinus mucocele with occular symptoms: A case series. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022. 74: 1109-12

48. Mohebbi A, Jahandideh H, Harandi AA. Sphenoid sinus mucocele as a cause of isolated pupil-sparing oculomotor nerve palsy mimicking diabetic ophthalmoplegia. Ear Nose Throat J. 2013. 92: 563-5

49. Montone KT. Pathology of fungal rhinosinusitis: A review. Head Neck Pathol. 2016. 10: 40-6

50. Muneer A, Jones NS. Unilateral abducens nerve palsy: A presenting sign of sphenoid sinus mucocoeles. J Laryngol Otol. 1997. 111: 644-6

51. Naik PP, Bhatt K, Richards EC, Bates T, Jahshan F, Chavda SV. A rare case of fungal rhinosinusitis caused by Scedosporium apiopermum. Head Neck Pathol. 2021. 15: 1059-63

52. Padhye AA, Gutekunst RW, Smith DJ, Punithalingam E. Maxillary sinusitis caused by Pleurophomopsis lignicola. J Clin Microbiol. 1997. 35: 2136-41

53. Pagella F, Pusateri A, Matti E, Giourgos G, Cavanna C, De Bernardi F. Sphenoid sinus fungus ball: Our experience. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011. 25: 276-80

54. Pinzer T, Reiss M, Bourquain H, Krishnan KG, Schackert G. Primary aspergillosis of the sphenoid sinus with pituitary invasion-a rare differential diagnosis of sellar lesions. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2006. 148: 1085-90

55. Ponikau JU, Sherris DA, Kern EB, Homburger HA, Frigas E, Gaffey TA. The diagnosis and incidence of allergic fungal sinusitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999. 74: 877-84

56. Saberhagen C, Klotz SA, Bartholomew W, Drews D, Dixon A. Infection due to Paecilomyces lilacinus A challenging clinical identification. Clin Infect Dis. 1997. 25: 1411-3

57. Saravanan K, Panda NK, Chakrabarti A, Das A, Bapuraj RJ. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis: An attempt to resolve the diagnostic dilemma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006. 132: 173-8

58. Schubert MS, Goetz DW. Evaluation and treatment of allergic fungal sinusitis. I. Demographics and diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998. 102: 387-94

59. Sethi DS, Lau DP, Chan C. Sphenoid sinus mucocoele presenting with isolated oculomotor nerve palsy. J Laryngol Otol. 1997. 111: 471-3

60. Sethi DS. Isolated sphenoid lesions: Diagnosis and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999. 120: 730-6

61. Shin SH, Ponikau JU, Sherris DA, Congdon D, Frigas E, Homburger HA. Chronic rhinosinusitis: An enhanced immune response to ubiquitous airborne fungi. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004. 114: 1369-75

62. Smith T, Goldschlager T, Mott N, Robertson T, Campbell S. Optic atrophy due to Curvularia lunata mucocoele. Pituitary. 2007. 10: 295-7

63. Soon SR, Lim CM, Singh H, Sethi DS. Sphenoid sinus mucocele: 10 cases and literature review. J Laryngol Otol. 2010. 124: 44-7

64. Taghian E, Abtahi SH, Mohammadi A, Hashemi SM, Ahmadikia K, Dolatabadi S. A study on the fungal rhinosinusitis: Causative agents, symptoms, and predisposing factors. J Res Med Sci. 2023. 28: 12

65. Tang IP, Brand Y, Prepageran N. Evaluation and treatment of isolated sphenoid sinus diseases. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016. 24: 43-9

66. Thakar A, Sarkar C, Dhiwakar M, Bahadur S, Dahiya S. Allergic fungal sinusitis: Expanding the clinicopathologic spectrum. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004. 130: 209-16

67. Thompson RF, Bode RB, Rhodes JC, Gluckman JL. Paecilomyces variotii An unusual cause of isolated sphenoid sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988. 114: 567-9

68. Thompson GR, Patterson TF. Fungal disease of the nose and paranasal sinuses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012. 129: 321-6

69. Vaphiades MS, Roberson GH. Sphenoid sinus mucocele presenting as a third cranial nerve palsy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2005. 25: 293-4

70. Villemure-Poliquin N, Nadeau S. Surgical treatment of isolated sphenoid sinusitis-a case series and review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021. 79: 18-23

71. Wang ZM, Kanoh N, Dai CF, Kutler DI, Xu R, Chi FL. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: An analysis of 122 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002. 111: 323-7

72. Watters GW, Milford CA. Isolated sphenoid sinusitis due to Pseudallescheria boydii. J Laryngol Otol. 1993. 107: 344-6

73. Yap HJ, Ramli RR, Yeoh ZX, Sachlin IS. Series of isolated sphenoid disease: Often neglected but perilous. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022. 10: 2050313X221097757

74. Yokoyama T, Inoue S, Imamura J, Nagamitsu T, Jimi Y, Katoh S. Sphenoethmoidal mucoceles with intracranial extension--three case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1996. 36: 822-8

75. Zhan G, Guo S, Hu H, Liao J, Dang R, Yang Y. Expanded endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach to determine morphological characteristics and clinical considerations of the cavernous sinus venous spaces. Sci Rep. 2022. 12: 16794