- Department of Orthopaedics, Lilavati Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India,

- Department of Orthopaedics, Somaiya Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India,

- Department of Orthopaedics, Diana, Princess of Wales Hospital, Grimsby, United Kingdom,

- Department of Orthopaedics and Spine Surgery, Bharat Ratna Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.

Correspondence Address:

Manojkumar B. Gaddikeri, Department of Orthopaedics, Lilavati Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_798_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Manojkumar B. Gaddikeri1, Sudhir K. Srivastava2, Praveen Patil3, Atif Naseem4, Harsh Agrawal4. Long-term operative outcome of giant calcified thoracic disc herniation – A retrospective analysis of 24 patients. 11-Nov-2022;13:526

How to cite this URL: Manojkumar B. Gaddikeri1, Sudhir K. Srivastava2, Praveen Patil3, Atif Naseem4, Harsh Agrawal4. Long-term operative outcome of giant calcified thoracic disc herniation – A retrospective analysis of 24 patients. 11-Nov-2022;13:526. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11990/

Abstract

Background: Thoracic disc herniations (TDHs) are rare (0.15–4%) and often cause significant myelopathy (70–95%). They are defined as “Giant” if they occupy >40% of the spinal canal. Further, they are ossified/calcified in 42% of cases, with a 70% incidence of intradural extension. Here, we reviewed our experience resecting 24 giant thoracic discs utilizing a posterolateral surgical approach.

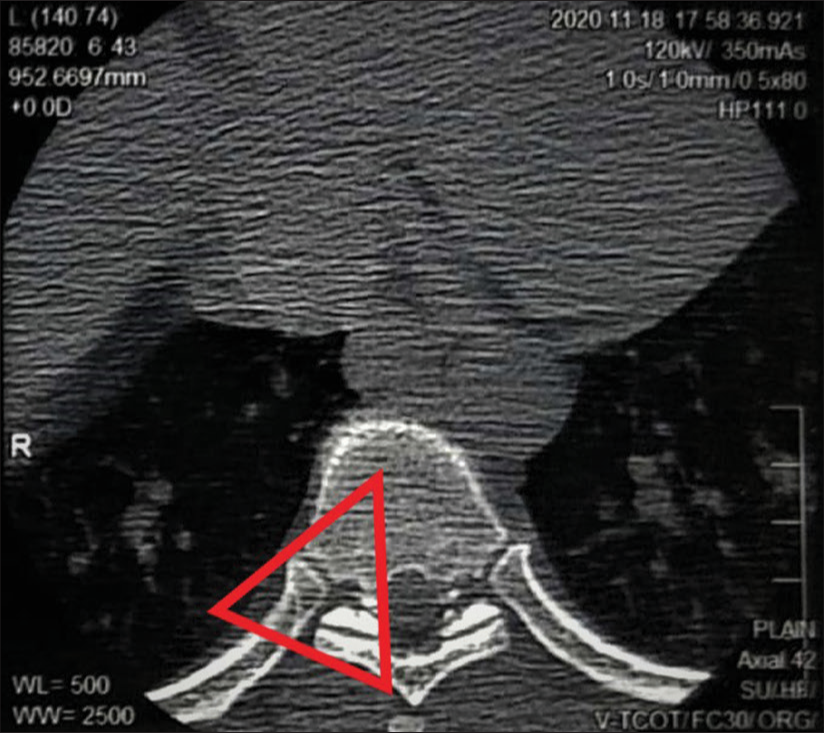

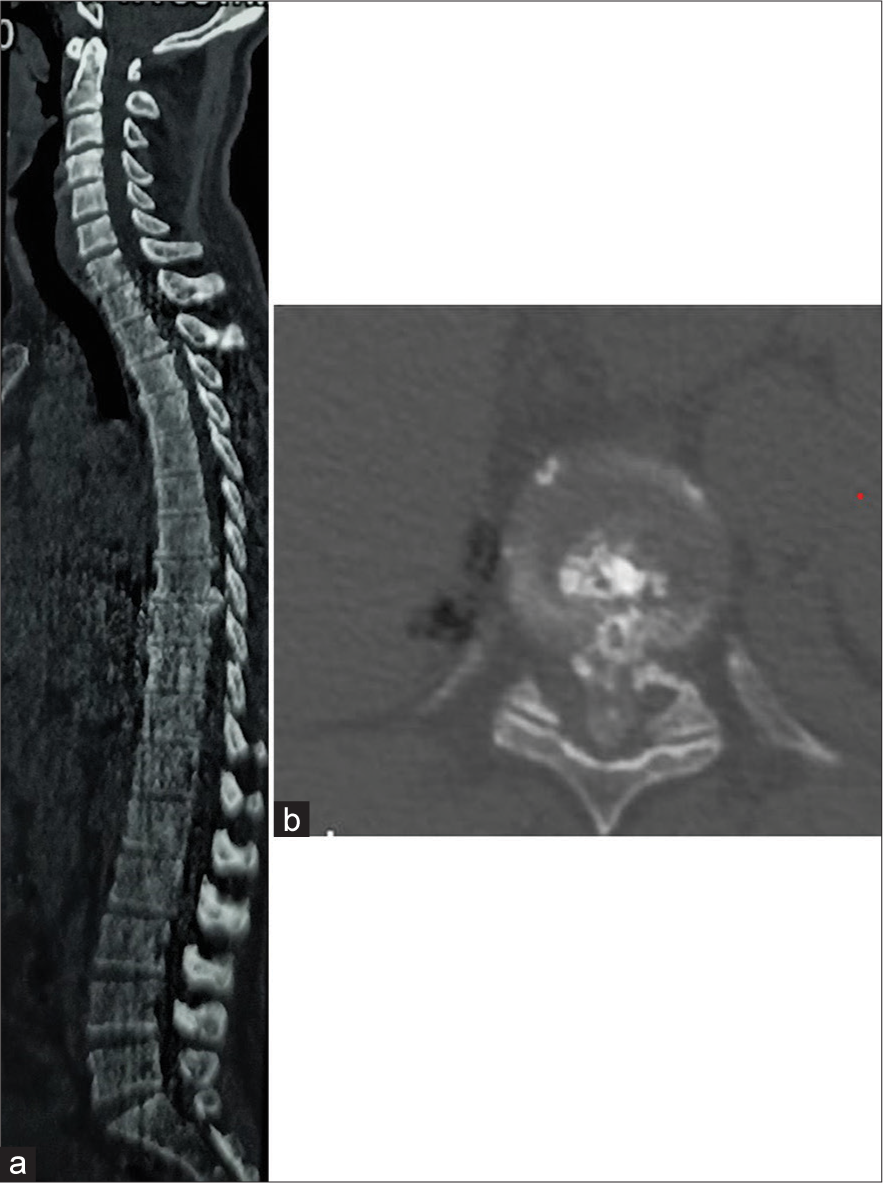

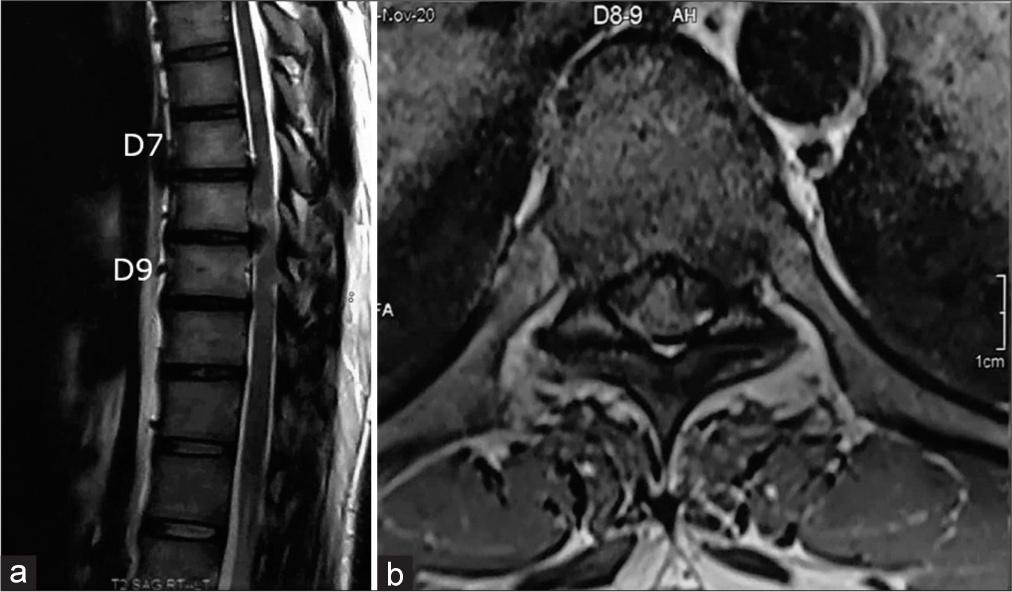

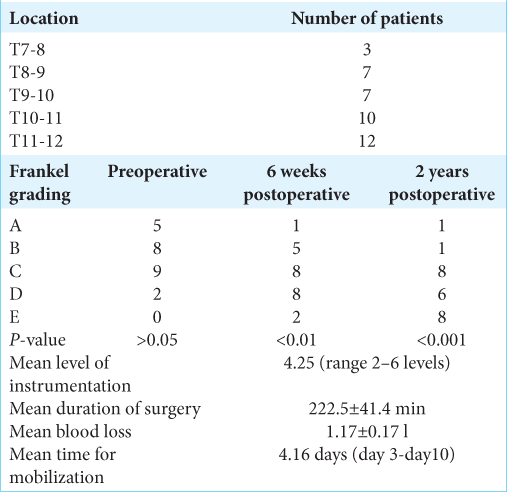

Methods: Over a 2-year period, we evaluated the outcomes for 24 patients averaging 40 years of age undergoing posterolateral resections of giant ossified/calcified TDH. We evaluated multiple clinical and radiographic parameters; demographics, Frankel grades, surgical time, perioperative complications, and number of levels involved. In addition, utilizing magnetic resonance/computed tomography studies, we documented that the most commonly involved level was T11–T12, and the average canal occupancy ratio (i.e., degree of canal encroachment) was 58.2 ± 7.72%.

Results: Neurological improvement was seen in 22 of the 24 patients; none experienced neurological deterioration over the average 2-year post-operative period. Six complications occurred; three dural tears and three suture site infections.

Conclusion: The posterolateral approach proved to be safe and effectively for resecting 24 giant ossified/calcified TDH with minimum complications.

Keywords: Calcified disc, Giant thoracic disc herniations, Posterolateral approach

INTRODUCTION

Thoracic disc herniations (TDHs) are rare and occur with a frequency of 1 in a million. They make up to 0.15–4% of all surgery for disc herniations and are symptomatic typically in the elderly patients. They are labeled as “giant” when they occupy more than 40% of the spinal canal on magnetic resonance or computed tomography studies; notably, 15–70% exhibit concomitant intradural extension. Surgery in myelopathic patients may be performed anteriorly, posteriorly, posterolaterally, laterally, or circumferentially. Here, we reviewed 24 patients with giant TDH who underwent successful posterolateral resections with limited morbidity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

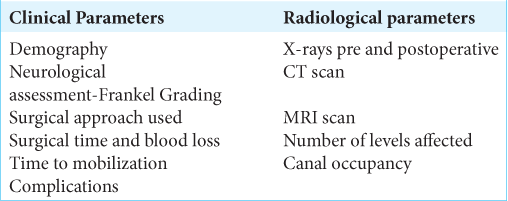

Over a 2-year period, 24 patients with giant ossified/calcified TDH underwent posterolateral surgery. Multiple clinical and radiographic parameters were followed at 1, 3, 6 months, and 1 at 1 and 2 years postoperatively [

Surgical technique

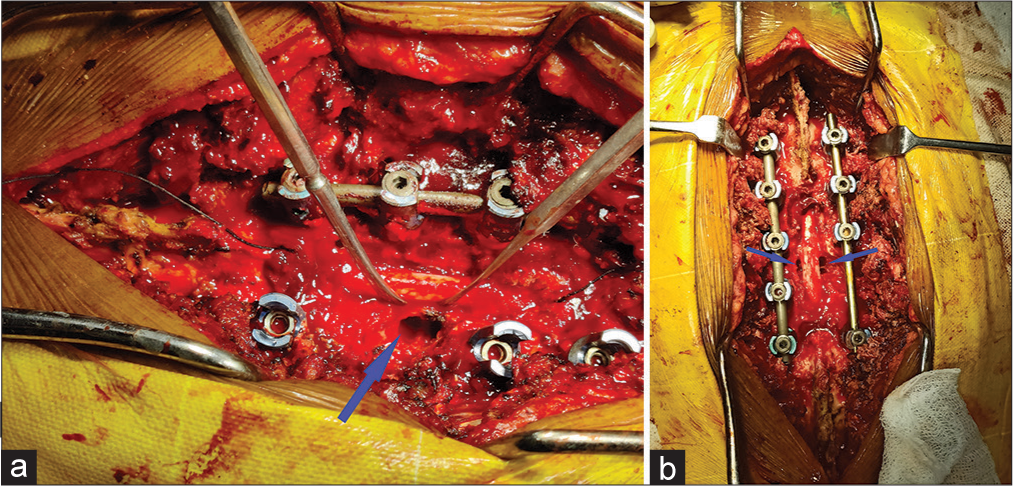

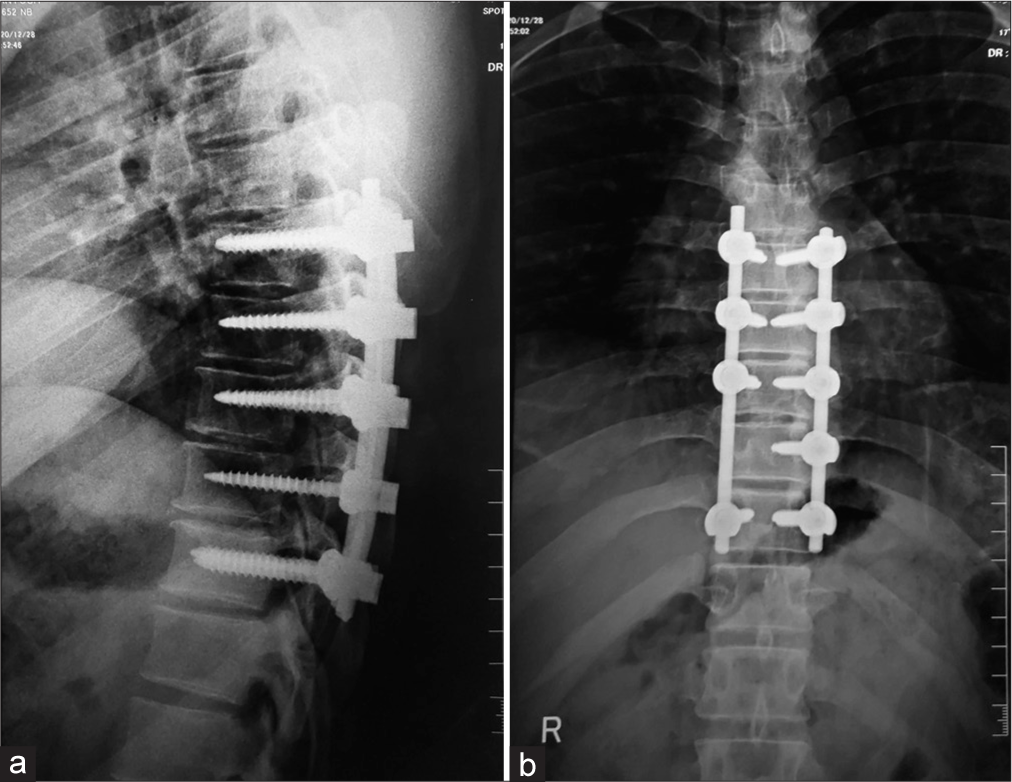

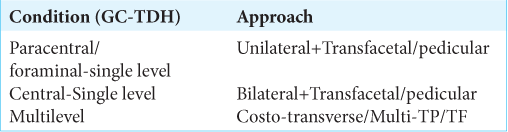

Through a standard mid-line posterior skin incision, posterolateral approaches (i.e., transfacetal, transpedicular, or costotransversectomy) [

RESULTS

Postoperative neurological Frankel grades

No patient exhibited immediate postoperative neurological deterioration, nor was there worsening in their Frankel Grades over 2 postoperative years. Their postoperative Frankel Grades included: 1 with Frankel-A, 1 with Frankel-B, 8 with Frankel-C, 6 with Frankel-D, and 8 with Frankel-E [

Extent of surgery

Patients underwent and an average of 4.25 (range 2–6 levels) levels of instrumentation, with mean surgical times of 222.5 ± 41.4 min; the average blood loss of 1.17 ± 0.17 l. They were mobilized an average of 4.16 days postoperatively (ranging from 3 to 10 days).

Complications

Six patients had postoperative complications. Three had dural tears managed by direct suturing using Prolene 5–0 and reenforced with fat patches (Note that we now realize that Prolene sutures typically unfurl and are NOT the best sutures to use in these cases). All three patients were managed with a postoperative dural leak protocol. Another three patients had suture site complications which were managed conservatively. No patient required revision surgery.

DISCUSSION

Choice of operative approaches

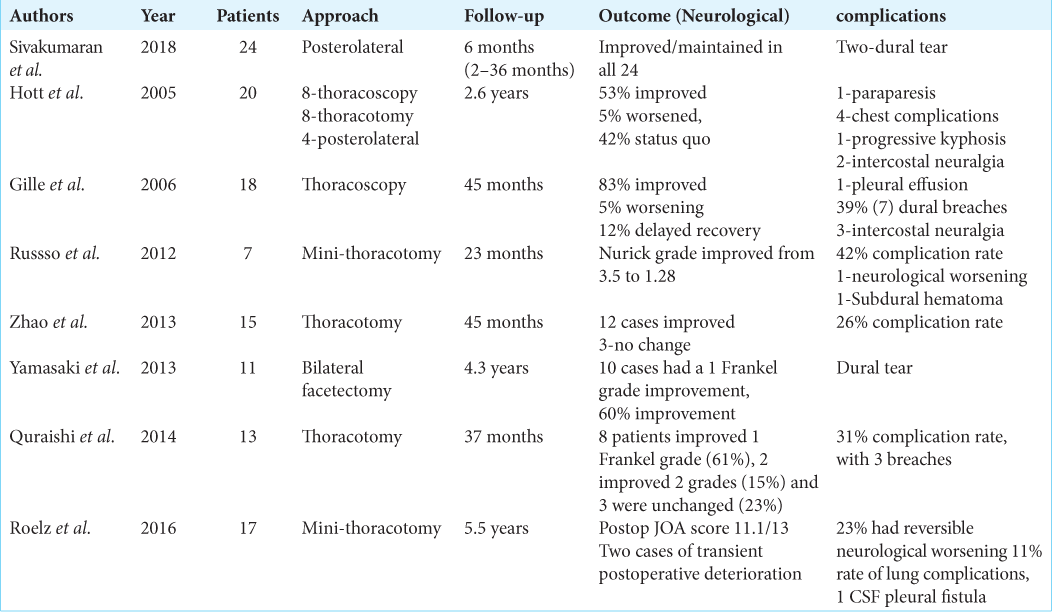

There are multiple approaches to giant TDH documented in the literature. Although anterior approaches provide excellent view of the central herniated disc and allow for thorough decompression, there is a high morbidity rate and a steep learning curve for thoracotomy or thoracoscopy (i.e., complication rates 21–39%).[

Mean canal occupancy ratio of TDH and accompanying risks/complications

Thoracic canal compression beyond 40%, as with giant TDH, has typically results in significant myelopathy. Our mean canal occupancy ratio was 58.2 ± 7.72% and indeed; our patients were myelopathic as indicated by their preoperative Frankel Grades [

Surgical times for posterolateral surgical approaches to giant TDH

The average surgical times for posterolateral resection of giant TDH are shorter than for other approaches;[

CONCLUSION

We successfully utilized posterolateral approaches to remove giant ossified/calcified TDH in 24 patients.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

Acknowledgment

No conflicts of interest from any of the authors.

References

1. Court C, Mansour E, Bouthors C. Thoracic disc herniation: Surgical treatment. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018. 104: S31-40

2. Gille O, Soderlund C, Razafimahandri HJ, Mangione P, Vital JM. Analysis of hard thoracic herniated discs: Review of 18 cases operated by thoracoscopy. Eur Spine J. 2006. 15: 537-42

3. Hott JS, Feiz-Erfan I, Kenny K, Dickman CA. Surgical management of giant herniated thoracic discs: Analysis of 20 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005. 3: 191-7

4. Quraishi NA, Khurana A, Tsegaye MM, Boszczyk BM, Mehdian SM. Calcified giant thoracic disc herniations: Considerations and treatment strategies. Eur Spine J. 2014. 23: 76-83

5. Roelz R, Scholz C, Klingler JH, Scheiwe C, Sircar R, Hubbe U. Giant central thoracic disc herniations: Surgical outcome in 17 consecutive patients treated by mini-thoracotomy. Eur Spine J. 2016. 25: 1443-51

6. Russo A, Balamurali G, Nowicki R, Boszczyk BM. Anterior thoracic foraminotomy through mini-thoracotomy for the treatment of giant thoracic disc herniations. Eur Spine J. 2012. 21: S212-20

7. Sivakumaran R, Uschold TD, Brown MT, Patel NR. Transfacet and transpedicular posterior approaches to thoracic disc herniations: Consecutive case series of 24 patients. World Neurosurg. 2018. 120: e921-31

8. Yamasaki R, Okuda S, Maeno T, Haku T, Iwasaki M, Oda T. Surgical outcomes of posterior thoracic interbody fusion for thoracic disc herniations. Eur Spine J. 2013. 22: 2496-503

9. Zhao Y, Wang Y, Xiao S, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Liu B. Transthoracic approach for the treatment of calcified giant herniated thoracic discs. Eur Spine J. 2013. 22: 2466-73