- Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Beneficência Portuguesa de Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brazil

- Unifacisa, Unifacisa-University Center, Department of Medicine, R. Manoel Cardoso Palhano, Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brazil

Correspondence Address:

Raivson Diogo Felix Fernandes, Unifacisa, Unifacisa-University Center, Department of Medicine, R. Manoel Cardoso Palhano, Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brazil.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_289_2024

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Breno Nery1, Raivson Diogo Felix Fernandes2, Emanuella Arruda do Rego Nobrega2, Arthur Cellys Tavares da Silva2, Maisa Souza Liebig2, Clarissa Cartaxo Eloy Nóbrega2, Julia Lopes Braga2, Thayna Dantas Souto Fernandes2, Eduardo Quaggio1, Jose Alencar De Sousa Segundo1. Mature congenital intraventricular intracranial teratoma: A case report and literature review. 26-Jul-2024;15:259

How to cite this URL: Breno Nery1, Raivson Diogo Felix Fernandes2, Emanuella Arruda do Rego Nobrega2, Arthur Cellys Tavares da Silva2, Maisa Souza Liebig2, Clarissa Cartaxo Eloy Nóbrega2, Julia Lopes Braga2, Thayna Dantas Souto Fernandes2, Eduardo Quaggio1, Jose Alencar De Sousa Segundo1. Mature congenital intraventricular intracranial teratoma: A case report and literature review. 26-Jul-2024;15:259. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/13011/

Abstract

Background: Intracranial teratomas represent a rare subset of neoplasms characterized by tissues derived from multiple germ layers within the cranial cavity. These tumors, originating from primordial germ cells, exhibit diverse clinical presentations and histopathological features. While predominantly located along the midline axis, including the suprasellar cistern and pineal region, they can also manifest in less common areas such as ventricles and hypothalamic regions. Histopathologically, they are classified as mature, immature, or malignant based on the degree of tissue differentiation.

Case Description: Male patient with prenatal care for congenital hydrocephalus born at 38 weeks gestation with a bulging fontanelle. Postnatal imaging revealed an intraventricular lesion, later diagnosed through magnetic resonance imaging as a mature teratoma invading the lateral ventricle and extending to the hypothalamus. Surgical resection achieved total macroscopic removal followed by successful postoperative ventriculoperitoneal shunting due to evolving hydrocephalus.

Conclusion: Teratomas are uncommon tumors, and prognosis depends on tumor size and location, especially considering the rarity of mature teratomas. Complete surgical resection is paramount for treatment, leading to a better prognosis and quicker recovery. In cases where complete removal is challenging, adjuvant therapies and cerebrospinal fluid diversion may be required to enhance therapeutic outcomes and ensure successful resection.

Keywords: Brain neoplasms, Congenital, Teratoma

INTRODUCTION

Intracranial teratomas were first described in 1864 by Breslau and Rindfleisch through findings of massive intracranial tumors.[

The most common clinical manifestations that arouse suspicion during prenatal imaging are often macrocephaly, hydrocephalus, and polyhydramnios, which suggest the growth of an intracranial mass.[

Neurosurgical treatment with total tumor resection is considered the therapeutic option of choice and should be approached according to the patient’s clinical stability and the tumor findings found in imaging studies. Successfully treated cases are rare, and the treatment success rate is attributed to the location, extent, and histological composition.[

This report describes a case of mature intracranial teratoma in which congenital hydrocephalus was the clinical manifestation during prenatal care. The importance of documenting this case report lies in underscoring the significance of prompt diagnosis and appropriate management strategies to enhance patient outcomes. In addition, by presenting this case, we aim to contribute to the existing body of literature on intracranial teratomas and further elucidate their clinical presentation, diagnostic process, and therapeutic considerations.

CASE DESCRIPTION

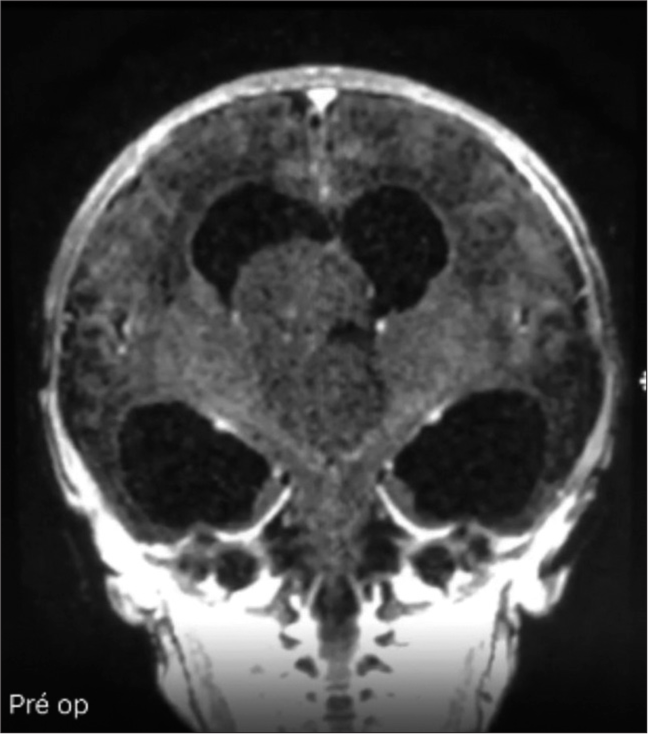

Male patient, in prenatal care due to congenital hydrocephalus of undefined etiology, born at 38 weeks of gestation, weight 2.9 kg, and APGAR score 9/10. After birth, transfontanellar ultrasonography was performed, which showed intraventricular lesions. The diagnosis of intracranial teratoma in the following case was made by means of complementary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which showed an expansive and homogeneous intraventricular lesion, without contrast, isointense to the brain parenchyma, with surrounding calcified material, invading the body and anterior horn of the right lateral ventricle, and extending through the third ventricle to the hypothalamus [

A differential diagnosis that was considered was ependymoma, which is a neoplasm composed of neoplastic ependymal cells affecting mainly children and young adults. However, most ependymomas are located in the posterior fossa, and more than half of those located in the intraventricular region are located in the fourth ventricle. On non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scans, intraventricular ependymomas appear as isodense lesions with calcifications, whereas contrast-enhanced CT scans show heterogeneous enhancement. On MRI, solid or mixed solid-cystic tumors may be seen.

The surgical treatment of the case was performed after 6 days of the patient’s life by means of a right frontal craniotomy, with total macroscopic resection by transcortical approach, through the right middle frontal gyrus, associated with access through the choroidal fissure that was already dilated by the tumor, allowing access to the third ventricle [

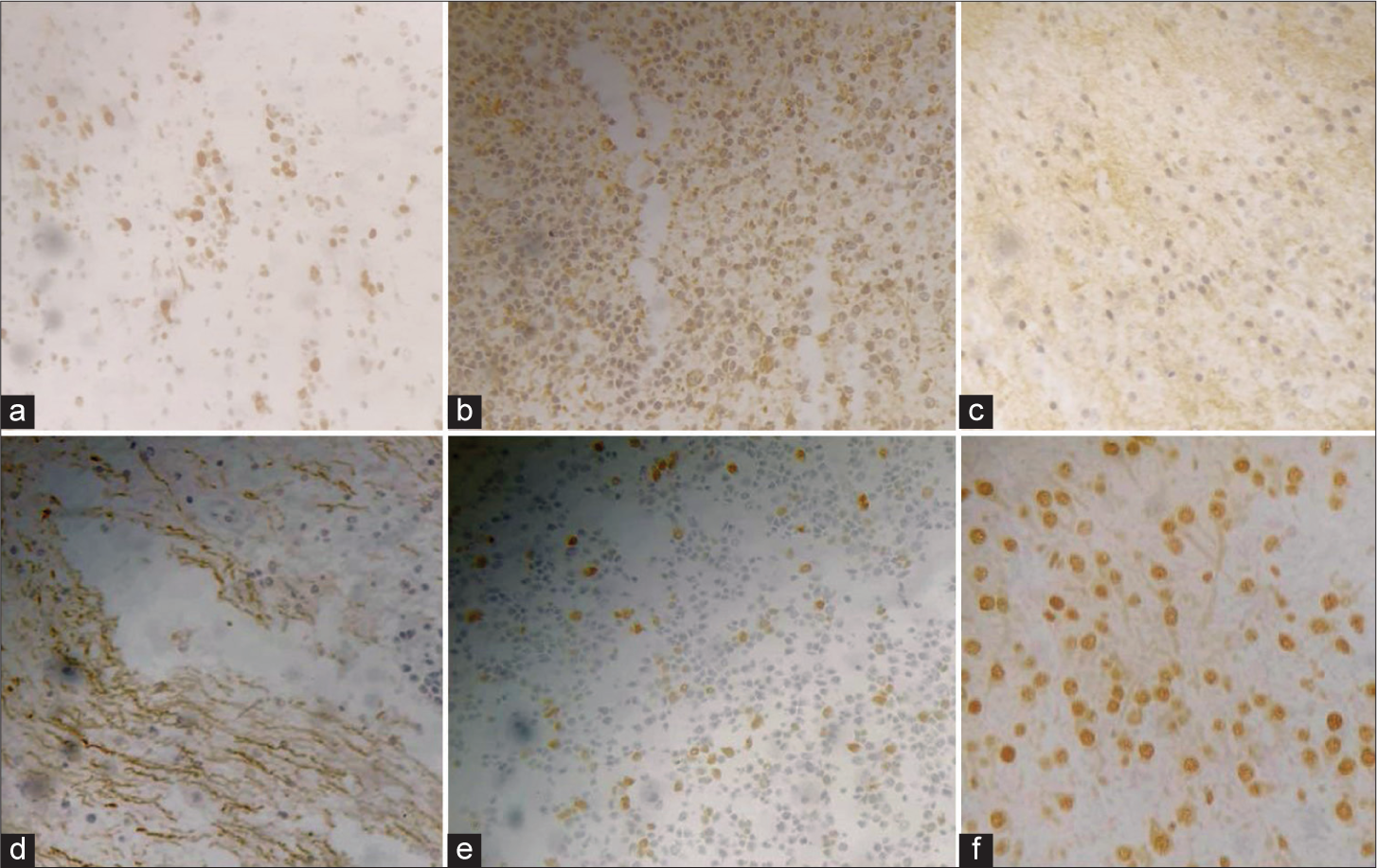

Figure 5:

Immunohistochemical examination. (a) KI-67 positive, reaching about 8% in hot spots. (b) Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is positive in areas of interest. (c) Synaptophysin is positive in areas of neuronal differentiation. (d) Neurofilament is positive in areas of neuronal differentiation. (e) Olig-2 positive in a few cells of interest. (f) Alpha thalassemia/mental retardation X-linked (ATRX) is positive in cells of interest.

The child remained under observation in the intensive care unit for 48 hours after surgery, developed hypertensive hydrocephalus in the following 2 weeks, and a ventriculoperitoneal shunt was performed without complications and with resolution of symptoms, with the patient being discharged from the hospital 3 days after the shunt. During follow-up, the patient manifested epilepsy after 7 months of surgery and continued with infantile spasms from 7 to 12 months of age until the seizures were controlled with the use of the medication levetiracetam. At present, the patient is in postoperative control for 30 months, with no recurrences, and continues to use the medication. The patient is undergoing physiotherapeutic follow-up treatment and presents mild hypotonia in the lower limbs associated with slight external rotation and abduction. He is using daily and bilateral suropodalic orthosis to improve bipedal support in standing and gait support. The patient performs independent walking, with preserved static and sound balance, transferring weight onto both feet during walking, and can develop quick and coordinated movements in a static position and while walking. His range of motion remains normal, without contractures. He presents satisfactory improvement from the proposed intervention and continuous physiotherapeutic treatment for better results. However, the patient is in the expected development parameters for his age.

DISCUSSION

This discussion is based on a literature review composed of articles from the PubMed database. To search for articles, the following keywords were entered: “Teratoma,” “intracranial,” and “congenital,” and the Boolean operator “AND” were used to combine the keywords and increase the number of studies published in the database. The inclusion criteria were the following: case reports of congenital intracranial teratomas and articles that addressed cases of mixed teratoma or those with a predominantly extracranial location and approach, and also that were studies in a language other than Portuguese, English, and Spanish were excluded from the study. There were no time duration filters. Thus, 205 articles were found and from them, only 58 studies met the established criteria and served as a basis for our discussion. In the preparation of

Teratomas represent a rare class of neoplasms characterized by the presence of tissues derived from the three primordial germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm.[

In newborns, teratomas tend to manifest predominantly in areas such as the skull, neck, and sacrococcygeal region, while in adults and adolescents, the most frequently affected sites are the gonads, the retroperitoneum, and also the sacrococcygeal region.[

Intracranial teratomas tend to arise in the midline so that 81– 95% are along an axis that runs from the suprasellar cistern to the pineal region, with common regions for the location being the pineal region, suprasellar region, and the cerebral hemispheres.[

Based on the case reports analyzed for this study, it is found that immature intracranial teratomas have a significant incidence, representing more than 60% of the cases of congenital teratomas in this region. No statistically significant differences were identified in relation to the sex of the affected patients, and the most common mode of delivery is a cesarean section, particularly when a teratoma is diagnosed during the fetal period. The prognosis of these patients remains unfavorable, with an approximate survival rate of 22.39%, evidencing the complexity and severity of this condition. It is important to note that a significant portion of the studies reviewed did not provide sufficiently detailed information to allow a more comprehensive statistical analysis, and the figures presented reflect a general synthesis of the characteristics available in the studies examined.

At present, a significant proportion of congenital intracranial teratomas are detected by fetal ultrasound during the prenatal period, predominantly in the third trimester of pregnancy.[

The use of fetal MRI is the preferred imaging modality for evaluating the morphological characteristics of the tumor and for guiding the neurosurgery team in defining management and prognostic strategies[

The location and size of the teratoma are considered significant prognostic factors. In the case of localization, most reports showed a better outcome for supratentorial localization due to the location offering a more accessible surgical approach.[

The preferred treatment is complete surgical excision, as illustrated in our study, given the rapid growth of these tumors and the curative potential of resection. Adjuvant therapies can be used when total resection is not possible, aiming to slow tumor growth and reduce tumor size and vascularization, thus facilitating total tumor resection with a lower incidence of complications and mortality.[

As in our case, it is common for it to be necessary to perform a cerebrospinal fluid bypass due to hydrocephalus caused by the growth of the teratoma tumor mass.[

CONCLUSION

In our reported case, the identification of hydrocephalus in the prenatal period served as a crucial indicator despite no detectable changes in the ultrasound examination were evident at this point. The efficient identification of the teratoma after birth enabled subsequent successful management, highlighting the fundamental role of total tumor resection in achieving favorable outcomes. In addition, the case underscores the necessity of adjusting the surgical strategies depending on the tumor’s position and properties, especially in areas where endoscopic removal was deemed inefficient and the open route was chosen. The postoperative management of hydrocephalus through ventriculoperitoneal shunting exemplifies the multidisciplinary approach necessary for the comprehensive treatment of these cases. Despite the fact that it was not used in our case, recent studies have shown that adjuvant therapy has also proved to be useful in such cases of intracranial teratomas, particularly when resection is insufficient.

The analysis of the presented case study reveals the importance of case-specific conclusions and a multidisciplinary treatment plan. Each case offers unique insights into diagnostic challenges, surgical considerations, and postoperative care, thereby enriching the existing literature and informing future clinical practices.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Algahtani HA, Al-Rabia MW, Al-Maghrabi HQ, Kutub HY. Posterior fossa teratoma. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2013. 18: 371-4

2. Arslan E, Usul H, Baykal S, Acar E, Eyüboğlu EE, Reis A. Massive congenital intracranial immature teratoma of the lateral ventricle with retro-orbital extension: A case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2007. 43: 338-42

3. Baykaner MK, Ergun E, Cemil B, Bayik P, Emmez H. A mature cystic teratoma in pineal region mimicking parietal encephalocele in a newborn. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007. 23: 573-6

4. Berlin AJ, Rich LS, Hahn JF. Congenital orbital teratoma. Childs Brain. 1983. 10: 208-16

5. Blitz MJ, Greeley E, Tam HT, Rochelson B. Use of external cephalic version and amnioreduction in the delivery of a fetal demise with macrocephaly secondary to massive intracranial teratoma. AJP Rep. 2015. 5: 77-9

6. Breslau A, Rindfleisch E. Birth history and investigation of a fetus-to-fetus case. Virchows Arch. 1864. 30: 406-17

7. Buetow PC, Smirniotopoulos JG, Done S. Congenital brain tumors: A review of 45 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990. 155: 587-93

8. Canan A, Gülsevin T, Nejat A, Tezer K, Sule Y, Meryem T. Neonatal intracranial teratoma. Brain Dev. 2000. 22: 340-2

9. Chien YH, Tsao PN, Lee WT, Peng SF, Yau KI. Congenital intracranial teratoma. Pediatr Neurol. 2000. 22: 72-4

10. Duckett S, Claireaux AE. Cerebral teratoma associated with epignathus in a newborn infant. J Neurosurg. 1963. 20: 888-91

11. Erman T, Göçer IA, Erdoğan S, Güneş Y, Tuna M, Zorludemir S. Congenital intracranial immature teratoma of the lateral ventricle: A case report and review of the literature. Neurol Res. 2005. 27: 53-6

12. Finck F, Antin R. Intracranial teratoma of the newborn. Am J Dis Child. 1965. 109: 439-42

13. Fradejas MR, García IG, Quispe AC, García AM, Higuera MI, Minguélez MR. Fetal intracranial immature teratoma: Presentation of a case and a systematic review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017. 30: 1139-46

14. Fukuoka K, Yanagisawa T, Suzuki T, Wakiya K, Matsutani M, Sasaki A. Successful treatment of hemorrhagic congenital intracranial immature teratoma with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014. 13: 38-41

15. Geethanath RM, Abdel-Salam F, editors. Congenital intracranial teratoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2010. pii: bcr0820092213

16. Gkasdaris G, Chourmouzi D. Congenital intracranial mature teratoma: The role of fetal MRI over ultrasound in the prenatal diagnosis and the perinatal management. BMJ Case Rep. 2019. 12: e229774

17. Hunt SJ, Johnson PC, Coons SW, Pittman HW. Neonatal intracranial teratomas. Surg Neurol. 1990. 34: 336-42

18. Im SH, Wang KC, Kim SK, Lee YH, Chi JG, Cho BK. Congenital intracranial teratoma: Prenatal diagnosis and postnatal successful resection. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003. 40: 57-61

19. Isaacs H. I. Perinatal brain tumors: A review of 250 cases. Pediatr Neurol. 2002. 27: 249-61

20. Johnston JM, Vyas NA, Kane AA, Molter DW, Smyth MD. Giant intracranial teratoma with epignathus in a neonate. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2007. 106: 232-6

21. Kitahara T, Tsuji Y, Shirase T, Yukawa H, Takeichi Y, Yamazoe N. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for facilitating surgical resection of infantile massive intracranial immature teratoma. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2016. 238: 273-8

22. Köken G, Yılmazer M, Şahin FK, Cosar E, Aslan A, Şahin O. Prenatal diagnosis of a fetal intracranial immature teratoma. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2007. 24: 368-71

23. Looi WS, Low DC, Low SY, Goh SH. Neonatal orbital swelling due to intracranial teratoma. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019. 104: F365

24. Maghrabi Y, Kurdi ME, Baeesa SS. Infratentorial immature teratoma of congenital origin can be associated with a 20-year survival outcome: A case report and review of literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2019. 17: 22

25. Milani HJ, Araujo Júnior E, Cavalheiro S, Oliveira PS, Hisaba WJ, Barreto EQ. Fetal brain tumors: Prenatal diagnosis by ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging. World J Radiol. 2015. 7: 17-21

26. Nanda A, Schut L, Sutton LN. Congenital forms of intracranial teratoma. Childs Nerv Syst. 1991. 7: 112-4

27. Nariai H, Price DE, Jada A, Weintraub L, Weidenheim KM, Gomes WA. Prenatally diagnosed aggressive intracranial immature teratoma-clinicopathological correlation. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2016. 35: 260-4

28. Nejat F, Kazmi SS, Ardakani SB. Congenital brain tumors in a series of seven patients. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2008. 44: 1-8

29. Noudel R, Vinchon M, Dhellemmes P, Litré CF, Rousseaux P. Intracranial teratomas in children: The role and timing of surgical removal. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008. 2: 331-8

30. Oommen J, Mohammed H, Ayyappan Kutty S, Mammen A, Kalathingal K, Thamunni CV. Neonatal teratoma: Craniofacial treatment. J Craniofac Surg. 2019. 30: 17-9

31. Păduraru L, Scripcaru DC, Zonda GI, Avasiloaiei AL, Stamatin M. Early intrauterine development of mixed giant intracranial teratoma in newborn: A case report. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015. 56: 851-6

32. Pinto V, Meo F, Loiudice L, D’Addario V. Prenatal sonographic imaging of an immature intracranial teratoma. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1999. 14: 220-2

33. Prause JU, Børgesen SE, Carstensen H, Fledelius HC, Jensen OA, Kirkegaard J. Cranio-orbital teratoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand Suppl. 1996. 219: 53-6

34. Rios LT, Araujo Júnior E, Nacaratto DC, Nardozza LM, Moron AF, da Glória Martins M. Prenatal diagnosis of intracranial immature teratoma in the third trimester using 2D and 3D sonography. J Med Ultrason. 2013. 40: 57-60

35. Rivera-Luna R, Medina-Sanson A, Leal-Leal C, PantojaGuillen F, Zapata-Tarrés M, Cardenas-Cardos R. Brain tumors in children under 1 year of age: Emphasis on the relationship of prognostic factors. Childs Nerv Syst. 2003. 19: 311-4

36. Rondinelli PI, Osório CA, Lopes LF. Intracranial germ cell tumors in childhood: Evaluation of fourteen cases. Neuropsychiatrist Arq. 2005. 63: 832-6

37. Suzuki I, Yoshida Y, Shirane R, Yoshimoto T. Neonatal intracranial tumor highly suspected of teratoma in the lateral ventricle consisting of multiple cysts: Case report. No Shinkei Geka. 1998. 26: 407-12

38. Takaku A, Mita R, Suzuki J. Intracranial teratoma in early infancy. J Neurosurg. 1973. 38: 265-8

39. Thoe J, Ducis K, Eldomery MK, Marshall M, Ferguson M, Vortmeyer AO. Pineal teratoma with nephroblastic component in a newborn male: Case report and review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2020. 80: 207-14

40. Tobit S, Valarezo J, Meir K, Umansky F. Giant cavernous sinus teratoma: A clinical example of a rare entity: Case report. Neurosurgery. 2001. 48: 1367-71

41. Whittle IR, Simpson DA. Surgical treatment of neonatal intracranial teratoma. Surg Neurol. 1981. 15: 268-73

42. Yang PJ, Graham AR, Carmody RF, Seeger JF, Capp MP. Intracranial mass in a neonate. Invest Radiol. 1986. 21: 360-4