- Department of Neurosurgery, Neurological Institute, Houston Methodist Hospital, Houston, Texas, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Sibi Rajendran, Department of Neurosurgery, Neurological Institute, Houston Methodist Hospital, Houston, Texas, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_714_2021

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Sibi Rajendran, Jonathan J. Lee, Hung Ba Le, Gavin Britz. Miliary pattern in secondary central nervous system T-cell lymphoma. 20-Jan-2022;13:25

How to cite this URL: Sibi Rajendran, Jonathan J. Lee, Hung Ba Le, Gavin Britz. Miliary pattern in secondary central nervous system T-cell lymphoma. 20-Jan-2022;13:25. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11351/

Abstract

Background: Secondary central nervous system lymphoma may manifest in a variety of ways on imaging, but most commonly presents with leptomeningeal disease, isolated parenchymal lesions, or both. We present a case of secondary central nervous system T-cell lymphoma with miliary pattern of spread noted on imaging.

Case Description: Our patient had known systemic T-cell lymphoma involving the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts and underwent stereotactic biopsy confirming secondary cerebral metastasis. This spread pattern is an uncommon manifestation of disease and in our experience carries a very poor prognosis.

Conclusion: We highlight the need to maintain a broad differential diagnosis that includes other metastatic disease and infectious etiologies, including toxoplasmosis and tuberculosis. High clinical suspicion and timely confirmatory testing including biopsy or cerebrospinal fluid flow cytometry are critical to treatment.

Keywords: CNS lymphoma, Miliary spread, T-cell lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) is a type of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that may manifest broadly, with multiorgan system involvement being common. Although classically linked to infection with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1, only about 5% of those infected may go on to develop ATLL.[

On imaging studies, leptomeningeal spread is the more common presentation of SCNSL, with only one-third of these patients having parenchymal disease.[

Here, we describe a miliary spread pattern of SCNSL in a patient with known systemic lymphoma involving the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts. A miliary spread pattern reflects small, innumerable focal lesions. Although the spread is often used to describe the spread of tuberculosis, the miliary pattern in the CNS have been reported in metastatic progression.[

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 61-year-old male with prior history of T-cell lymphoma with 3 months of chemotherapy presented to the emergency department with obtundation, fever, chills, and diarrhea. The patient also had a history of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism and was on therapeutic anticoagulation. His known lymphoma had infiltrated the bowel, causing typhlitis of the terminal ileum and cecum, along with pulmonary involvement, leading to bilateral pleural effusions with ground-glass opacification and alveolar opacities. His chemotherapy course was complicated by respiratory failure, sepsis, and acute tubular necrosis, all of which eventually resolved.

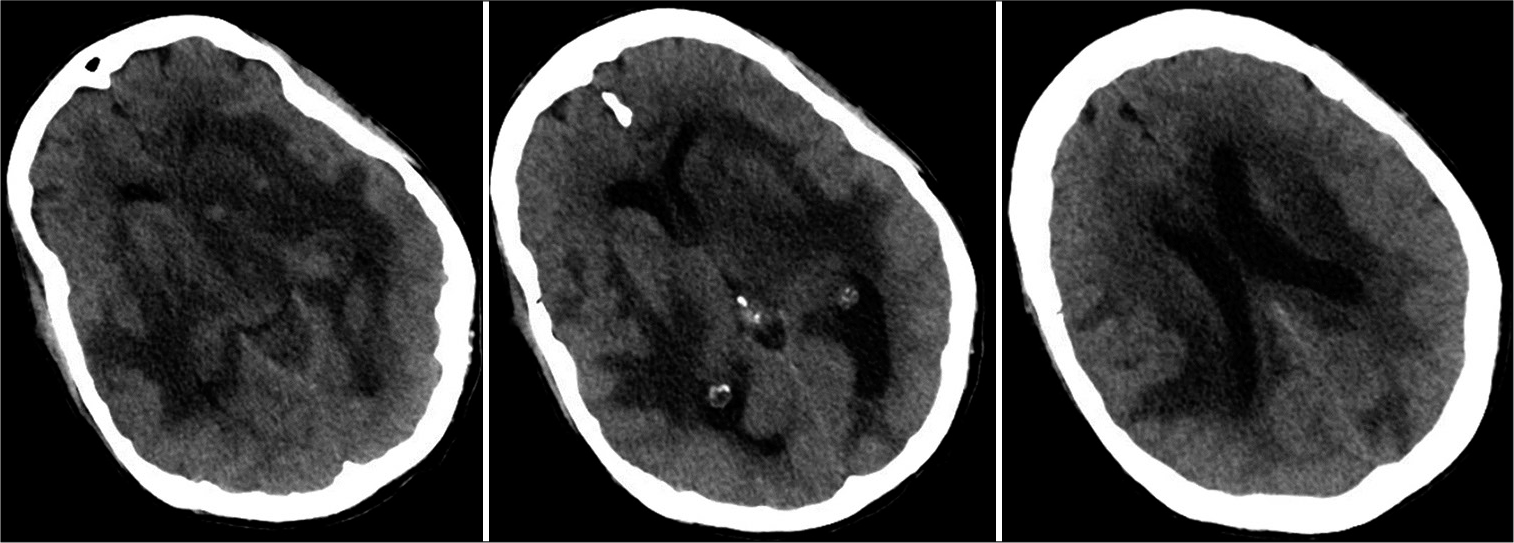

Before admission, imaging at an outside facility showed extensive vasogenic edema in the right frontal, left parietal, bilateral temporal, and left cerebellar regions. On arrival to hospital, the patient became unresponsive, with agonal breathing and unequal pupils. With concern for underlying herniation syndrome, level of care was escalated to the neurointensive care unit. Noncontrast computed tomography of the head revealed rounded, slightly dense intra-axial lesions in the left temporal, left basal ganglia, left occipital lobe, and right temporal lobe with extensive surrounding vasogenic edema [

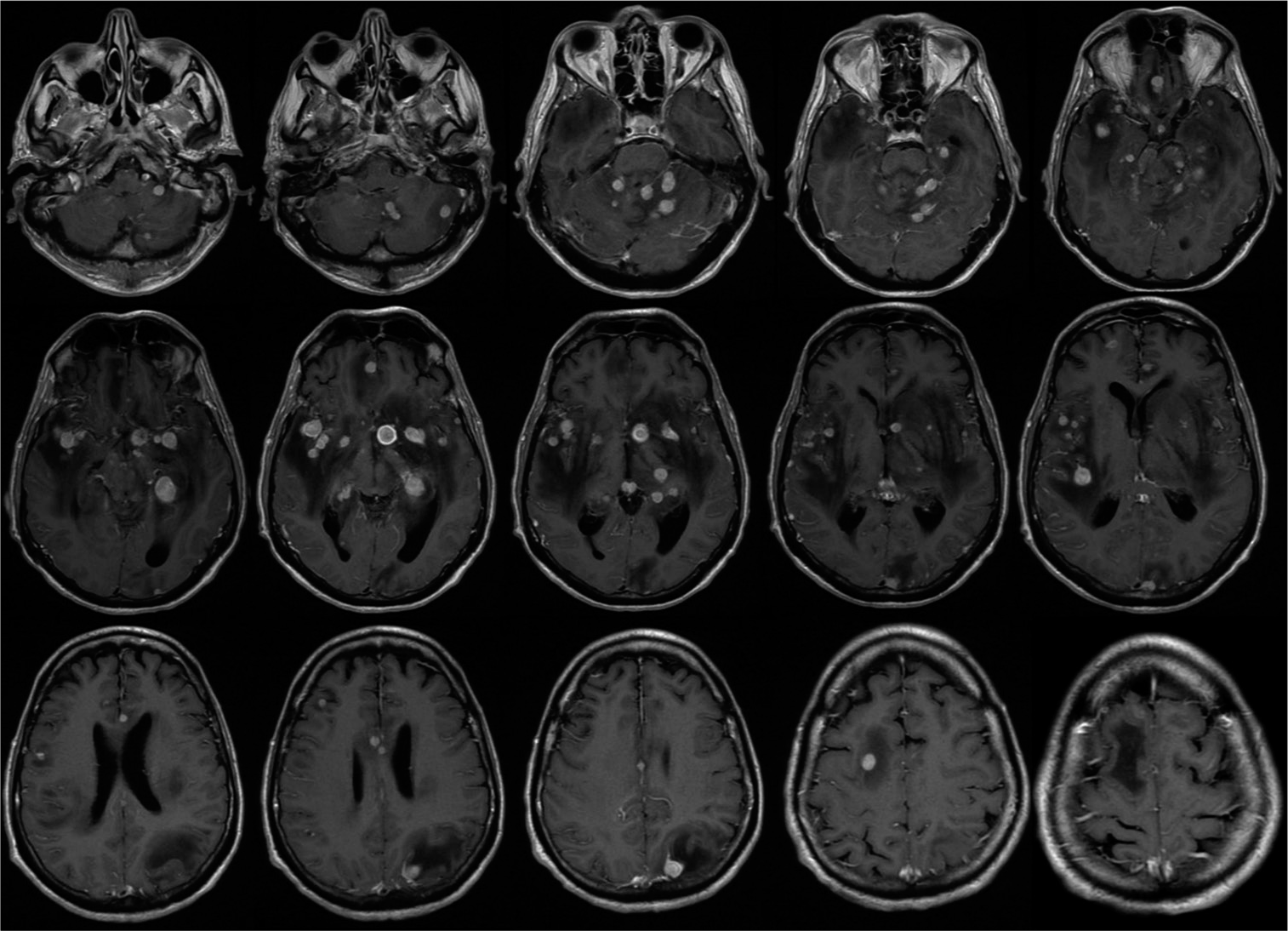

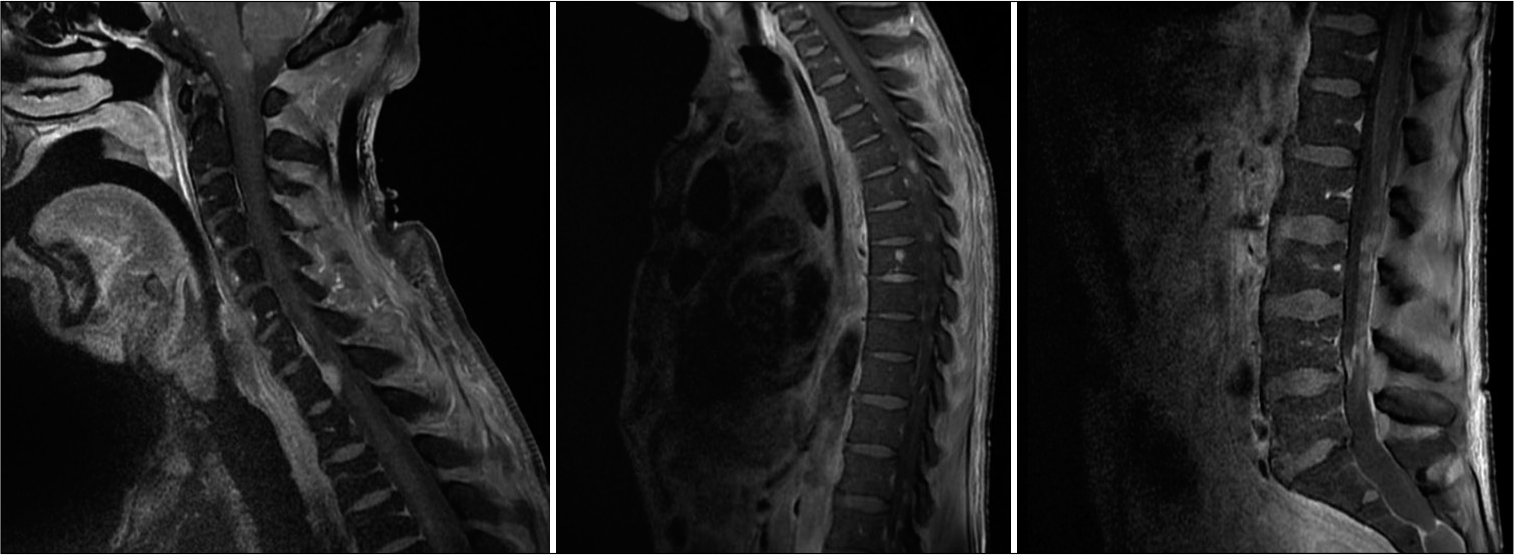

Contrast-enhanced MRI of the neuroaxis [

On postoperative day 1, the patient remained unresponsive and critically ill. Laboratory studies at this time revealed positive IgG antibody against toxoplasmosis. After infectious disease consultation, the patient was started on sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine for empiric toxoplasmosis treatment. On postoperative day 3, both pupils were 2 mm and nonreactive, and imaging showed communicating hydrocephalus. An external ventricular catheter was placed for intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring and therapeutic ventricular drainage. Emergency precautions for ICP included head of bed elevation, blood pressure control, and deep sedation. ICPs remained elevated despite this measure, and on postoperative day 7, the patient lost all brainstem reflexes, with bilateral fixed and dilated pupils. The patient developed severe thrombocytopenia requiring multiple platelet transfusions and hemodynamic instability requiring support with norepinephrine, phenylephrine, epinephrine, and vasopressin drips. After family discussion about goals of care and poor neurological prognosis, care was withdrawn and the patient expired.

DISCUSSION

Lymphomas may present in the CNS in many forms, often meaning a broad differential diagnosis exists when initially discovered. A solitary or few lesions in the CNS without any systemic involvement would raise concern for primary CNS lymphoma, especially in the context of an immunocompromised patient. Secondary CNS lymphoma (SCNSL) often presents with leptomeningeal enhancement, but when parenchymal disease is present, usually only manifests as a solitary mass or as a few lesions. Here, we described a case of miliary SCNSL, with innumerable ring-enhancing lesions throughout the brain, cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine.

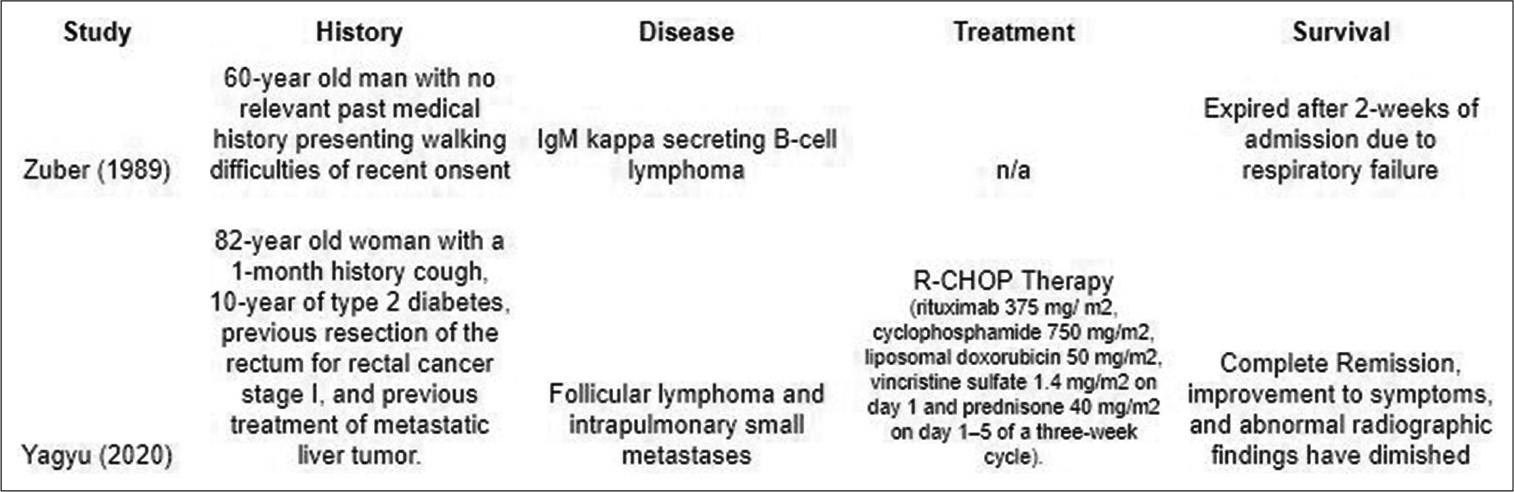

It is important to discuss the differential diagnosis when imaging studies show the miliary pattern of lesion spread. The percent of SCNSL (of any kind) presenting with miliary spread is difficult to quantify, with even case reports being scant, making a broad differential, especially important when suspicion exists. Infectious disease, including cerebral toxoplasmosis, neurocysticercosis, and certain fungal diseases, may present similarly. Metastatic disease from other cancers is also on the differential diagnosis, with case reports of melanomas and lung cancers in the literature presenting with miliary cerebral spread.[

OBSERVATIONS

Infectious disease may be a confounding variable when looking at imaging. As many patients with lymphoma are immunocompromised due to disease or treatment burden, opportunistic pathogens may lead to a convoluted clinical picture. Indeed, our patient even had positive IgG serology for toxoplasmosis and underwent empiric therapy. It is important here to realize that approximately one-third of the world’s population has IgG seropositivity for toxoplasma, making further confirmatory testing for active infection crucial.[

Finally, a point should be made on the rarity of SCNSL in general. While data are conflicting, it appears that T-cell lymphoma is in general more likely to have secondary CNS involvement, roughly twice as likely compared to B-cell lymphoma.[

CONCLUSION

SCNSL may present with a wide array of imaging findings. We present a case of a miliary spread of adult T-cell lymphoma in the brain, a rare imaging finding in SCNSL. Although the differential diagnosis for miliary disease is typically tuberculosis and other metastatic or infectious disease, lymphoma should be considered. Patients have a very poor prognosis with SCNSL in general, but this is especially true in those with this miliary spread pattern.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Arkenau HT, Chong G, Cunningham D, Watkins D, Agarwal R, Sirohi B. The role of intrathecal chemotherapy prophylaxis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2007. 18: 541-5

2. DeRosa P, Cappuzzo JM, Sherman JH. Isolated recurrence of secondary CNS lymphoma: Case report and literature review. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2014. 75: e154-9

3. Haldorsen IS, Espeland A, Larsson EM. Central nervous system lymphoma: Characteristic findings on traditional and advanced imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011. 32: 984-92

4. Kahveci R, Gürer B, Kaygusuz G, Sekerci Z. Miliary brain metastases from occult lung adenocarcinoma: Radiologic and histopathologic confirmation. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012. 3: 386-9

5. Konstantinovic N, Guegan H, Stäjner T, Belaz S, Robert-Gangneux F. Treatment of toxoplasmosis: Current options and future perspectives. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2020. 21: e00105

6. Maciocia P, Badat M, Cheesman S, D’Sa S, Joshi R, Lambert J. Treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with secondary central nervous system involvement: Encouraging efficacy using CNS-penetrating R-IDARAM chemotherapy. Br J Haematol. 2016. 172: 545-53

7. Malikova H, Burghardtova M, Koubska E, Mandys V, Kozak T, Weichet J. Secondary central nervous system lymphoma: Spectrum of morphological MRI appearances. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018. 14: 733-40

8. Pittman M, Treese S, Chen L, Frater JL, Nguyen TT, Hassan A. Utility of flow cytometry of cerebrospinal fluid as a screening tool in the diagnosis of central nervous system lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013. 137: 1610-8

9. Reiter FP, Giessen-Jung C, Dorostkar MM, Ertl-Wagner B, Denk GU, Heck S. Miliary pattern of brain metastases-a case report of a hyperacute onset in a patient with malignant melanoma documented by magnetic resonance imaging. Radiat Oncol. 2015. 10: 148

10. Smith A, Crouch S, Lax S, Li J, Painter D, Howell D. Lymphoma incidence, survival and prevalence 2004-2014: Sub-type analyses from the UK’s Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer. 2015. 112: 1575-84

11. Tobinai K. Current management of adult T-cell leukemia/ lymphoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 2009. 23: 1250-6

12. Vanneuville B, Janssens A, Lemmerling M, de Vlam K, Mielants H, Veys EM. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma presenting with spinal involvement. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000. 59: 12-4

13. Yagyu K, Kobayashi M, Ueda T, Uenishi R, Nakatsuji Y, Matsushita H. Malignant lymphoma mimics miliary tuberculosis by diffuse micronodular radiographic findings. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020. 31: 101239

14. Zuber M, Gheradi R, Defer G, Gaulard P, Divine M, Zafrani ES. Peripheral neuropathy, coagulopathy and nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver in a patient with multiple serologic auto-antibody activities and IgM B-cell lymphoma. J Intern Med. 1989. 226: 291-5