- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas, USA

- Department of Surgery, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas, USA

Correspondence Address:

Noojan Kazemi

Department of Neurosurgery, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas, USA

DOI:10.4103/sni.sni_439_16

Copyright: © 2017 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Daniel Chakhalian, Arunprasad Gunasekaran, Gautam Gandhi, Lucas Bradley, Jason Mizell, Noojan Kazemi. Multidisciplinary surgical treatment of presacral meningocele and teratoma in an adult with Currarino triad. 10-May-2017;8:77

How to cite this URL: Daniel Chakhalian, Arunprasad Gunasekaran, Gautam Gandhi, Lucas Bradley, Jason Mizell, Noojan Kazemi. Multidisciplinary surgical treatment of presacral meningocele and teratoma in an adult with Currarino triad. 10-May-2017;8:77. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/multidisciplinary-surgical-treatment-of-presacral-meningocele-and-teratoma-in-an-adult-with-currarino-triad/

Abstract

Background:Currarino syndrome (CS) is a rare genetic condition that presents with the defining triad of anorectal malformations, sacral bone deformations, and presacral masses, which may include teratoma. Neurosurgeons are involved in the surgical treatment of anterior meningoceles, which are often associated with this condition. The accepted surgical treatment is a staged anterior-posterior resection of the presacral mass and obliteration of the anterior meningocele.

Case Description:This case involved a 36-year-old female who presented with late onset of symptoms attributed to CS (e.g., presacral mass, anterior sacral meningocele, and sacral agenesis). She successfully underwent multidisciplinary single-stage approach for treatment of the anterior sacral meningocele and resection of the presacral mass. This required obliteration of the meningocele and closure of the dural defect. One year later, her meningocele had fully resolved.

Conclusion:While late presentations with CS are rare, early detection and multidisciplinary treatment including single-state anterior may be successful for managing these patients.

Keywords: Currarino syndrome, meningocele, sacral, teratoma

INTRODUCTION

Currarino syndrome (CS) is an autosomal dominant syndrome. The classical presentation is characterized by sacral agenesis, anorectal malformations, and a presacral mass. CS is rare in adults, but should be recognized early to avoid life threatening complications, e.g. meningitis, rectal fistulas, and an approximately 1% risk for malignant transformation.

There are multiple surgical approaches utilized to treat anterior sacral meningoceles (ASM) and presacral masses. The most common is a two-staged anterior-posterior approach that carries an increased risk of anorectal perforation leading to infection along with greater morbidity attributed to increases blood loss, operating time, and length of hospital stay. Here, we offer a single-staged approach wherein the anterior sacral meningocele and presacral mass were both treated in one sitting.[

CASE REPORT

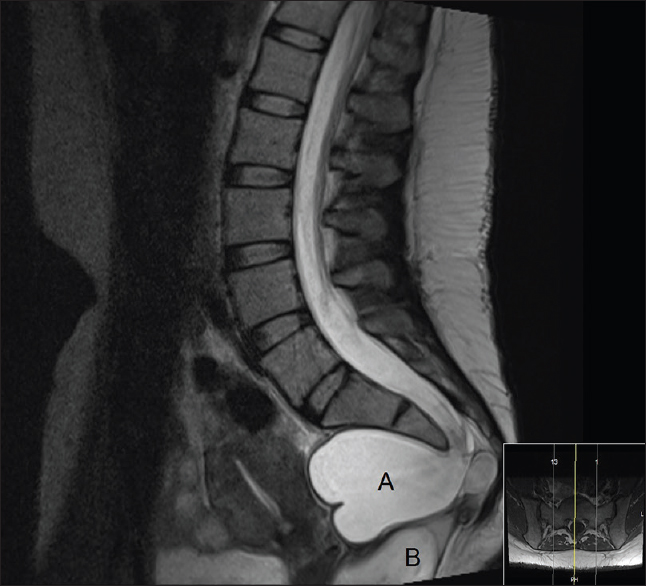

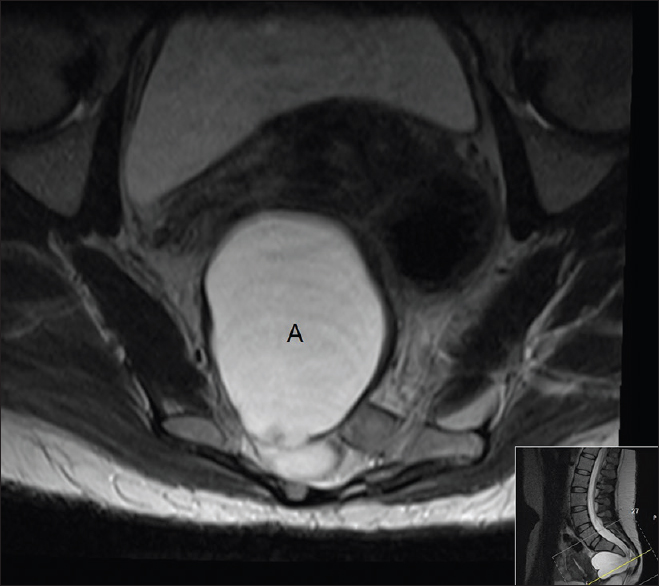

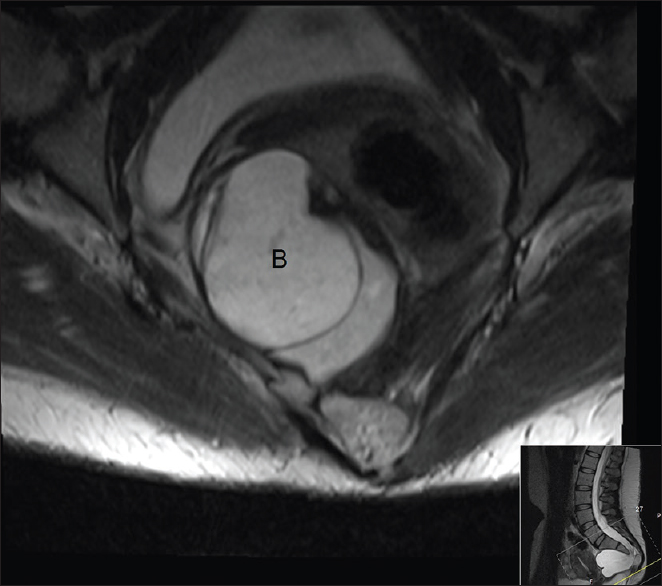

A 36-year-old female presented with intermittent constipation and bilateral lower extremity radiculopathy in the L4 distribution on the right and L5 distribution on the left. Family history was significant for the diagnosis of CS in both her children. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans revealed an incidental anterior sacral meningocele, a perirectal mass, with sacral agenesis, as well as right hemisacral hypoplasia, and an 8.0 cm × 8.0 cm × 6.0 cm meningocele emerging from a ventral sacral defect [Figures

Surgery

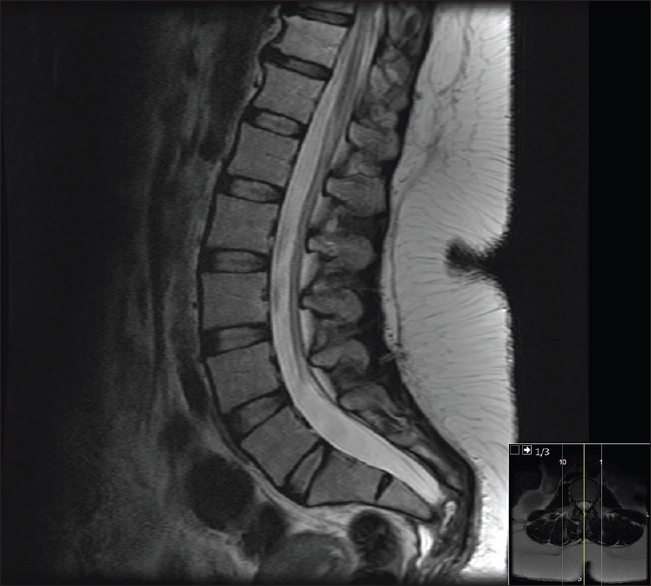

Surgical treatment of the meningocele required a complete S3-4 laminectomy with transdural closure and obliteration of the meningocele pedicle. The laminectomy, along with an extended incision to the anal sphincter, provided excellent exposure of the presacral mass. With the assistance of general surgery, the presacral mass was grossly excised without complications. Pathologically, this proved to be a mature teratoma. One year later, the myelomeningocele had fully resolved [

DISCUSSION

CS is a caudal regression syndrome typically associated with the classic triad of sacral malformations (sickle shaped sacrum, sacral agenesis below S2 [

Genetic discussion

This phenotype has been linked to loss of function mutations that disrupt the HLXB9 homeobox gene located on chromosome 7q36, and which encodes the HB9 nuclear protein. Although it is most commonly associated with nonsense mutations, a variety of mutations have been described including missense, splice site, and frameshift.[

Clinical diagnoses

More than 80% of the patients with the classic triad are diagnosed within the first decade of life.[

Surgical approaches

Classic CS is routinely treated in a two-staged approach with the anorectal malformation and presacral mass dealt separately from the obliteration of the anterior meningocele.[

CONCLUSION

While late presentation of CS is rare, early detection and multidisciplinary treatment including surgical resection is critical for the successful management of these patients because these lesions may undergo malignant transformation. Depending on the lesions present, a single-stage approach minimizes surgery and reduces its inherent risks including those of postoperative infection.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Aranda-Narvaez JM, Gonzalez-Sanchez AJ, Montiel-Casado C, Sanchez-Perez B, Jimenez-Mazure C, Valle-Carbajo M. Posterior approach (Kraske procedure) for surgical treatment of presacral tumors. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2012. 4: 126-30

2. Baltogiannis N, Mavridis G, Soutis M, Keramidas D. Currarino triad associated with Hirschsprung's disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2003. 38: 1086-9

3. Fitzpatrick MO, Taylor WA. Anterior sacral meningocele associated with a rectal fistula. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1999. 91: 124-7

4. Hagan DM, Ross AJ, Strachan T, Lynch SA, Ruiz-Perez V, Wang YM. Mutation analysis and embryonic expression of the HLXB9 Currarino syndrome gene. Am J Human Genet. 2000. 66: 1504-15

5. Lynch SA, Wang Y, Strachan T, Burn J, Lindsay S. Autosomal dominant sacral agenesis: Currarino syndrome. J Med Genet. 2000. 37: 561-6

6. Martucciello G, Torre M, Belloni E, Lerone M, Pini Prato A, Cama A. Currarino syndrome: Proposal of a diagnostic and therapeutic protocol. J Pediatr Surg. 2004. 39: 1305-11

7. Shoji M, Nojima N, Yoshikawa A, Fukushima W, Kadoya N, Hirosawa H. Currarino syndrome in an adult presenting with a presacral abscess: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014. 8: 77-

8. Yates VD, Wilroy RS, Whitington GL, Simmons JC. Anterior sacral defects: An autosomal dominantly inherited condition. J Pediatr. 1983. 102: 239-42