- Department of Neurosurgery, Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Concord Repatriation General Hospital, Concord, Australia,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Nepean Hospital, Kingswood, Sydney, Australia.

Correspondence Address:

Christopher Alan Brooks, Department of Neurosurgery, Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_178_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Christopher Alan Brooks1, Sameer Mahajan2, Wen Jie Choy3, Jayant Rajah3, Omprakash Damodaran2,3. Multiple non-contiguous anticoagulation-related spontaneous acute spinal intradural extramedullary hemorrhages. 03-Jun-2022;13:235

How to cite this URL: Christopher Alan Brooks1, Sameer Mahajan2, Wen Jie Choy3, Jayant Rajah3, Omprakash Damodaran2,3. Multiple non-contiguous anticoagulation-related spontaneous acute spinal intradural extramedullary hemorrhages. 03-Jun-2022;13:235. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11632/

Abstract

Background: Spinal intradural extramedullary hemorrhage is a rare and important pathology that may precipitate acute compressive myelopathy. It is most commonly associated with spinal trauma, neoplasia, vasculopathy, and iatrogenesis. In rare circumstances, it occurs spontaneously secondary to anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications without an underlying structural lesion. In these instances, it may be related to vasculopathy and/ or cardiovascular disease risk factors. We highlight the salient clinical and radiological features of this pathology, discuss putative mechanisms of its pathogenesis, and describe surgical considerations related to its management.

Case Description: This report describes an elderly gentleman who presented with two discrete spinal hemorrhages associated with separate foci of bleeding, in the context of therapeutic anticoagulation, on a background of significant structural and functional cardiovascular disease with risk factors.

Conclusion: Our report is novel in that there are no other cases, to the best of our knowledge, of multiple non-contiguous anticoagulation-related spontaneous acute spinal intradural extramedullary hemorrhages in the medical literature. This article is written with the purpose of assisting clinicians to recognize and expedite treatment of this rare pathology. Prompt diagnosis followed by urgent decompressive surgery provides the best functional outcomes.

Keywords: Anticoagulation, Extramedullary, Haemorrhage, Intradural, Spine

BACKGROUND

Spinal intradural extramedullary hemorrhage (SIEH) encompasses isolated and mixed, subarachnoid, and subdural bleeding of any cause.[

SIEH can rapidly develop into complete and irreversible paralysis and loss of function.[

In the present study, we report a case of a patient who developed acute lower back pain and paraplegia, secondary to a medication-induced coagulopathy. This study aims to raise awareness of a rare but highly morbid pathology, where prognosis is inversely related to the time between the onset of compression and decompressive surgery, and expeditious diagnosis is paramount to preservation of neurological function.

CASE DESCRIPTION

An independent 71-year-old male retiree presented to hospital with chest pain, thoracolumbar back pain, and hypertension (self-measured systolic blood pressure was elevated to 220 mmHg). He was evaluated for possible acute cardiac pathology. His medical history was significant for atrial fibrillation for which he was anticoagulated, and he had recently had an artificial cardiac pacemaker implanted for treatment of sinus node dysfunction. He had known hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and several benign skin lesions had been excised previously. While in the emergency department, his back pain escalated in severity. He had a headache and was vomiting. He was investigated for possible aortic pathology with computed tomography (CT) and bedside sonography, but there was no evidence of this. He was treated with analgesia.

He subsequently developed numbness and weakness of the right lower limb. This was only detected after several hours had passed, at which time he was re-evaluated for neurological pathology. CT imaging of the brain and circle of Willis revealed no abnormality of note. He was attributed a presumptive diagnosis of a likely anterior or posterior circulation embolic stroke and was admitted to the care of the inpatient cardiology service, with a plan for continuing anticoagulation (rivaroxaban was ceased in favor of enoxaparin), antiplatelet therapy (aspirin), and non-urgent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Later that evening, he was reviewed for persisting abdominal and back pain. He had developed allodynia of the lower chest and abdomen and had begun to retain urine, necessitating catheterization.

By day 3 of admission, his right lower limb paresis had progressed to flaccid paralysis and sensory loss. Our patient subsequently developed paresis of his left lower limb and loss of anal tone. He could not feel the tug of his catheter. There were no reflexes in his lower limbs, nor clonus. He could sense punctate stimuli but described the sensation as dull and paresthetic. He was finally referred to the inpatient neurosurgical service for consideration of spinal pathology.

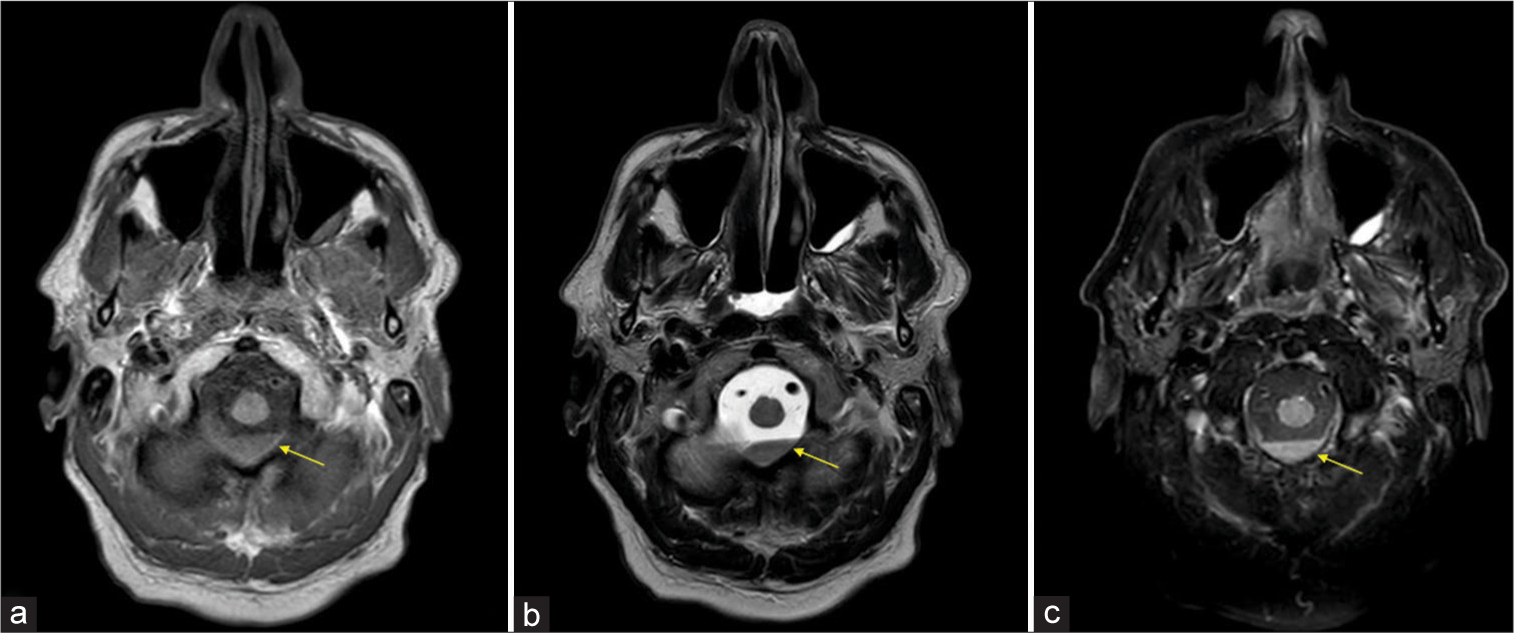

Emergent MRI of the entire spine and brain was performed. Two discrete foci of non-contiguous acute SIEH were discerned, approximately localized behind T1-2 and T10-11. There was associated spinal cord displacement and acute spinal cord edema due to compression, at both sites of hemorrhage. Our patient’s pre-operative radiology is depicted in

Figure 1:

Pre-operative sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the spine. (a) Cervicothoracic image demonstrating SIEH at T1/2. (b) Enlarged field of view (as indicated by the white arrow) over the region of hemorrhage in (a) with dimensions, demonstrating displacement of the cord anteriorly. Note the areas of cord signal change superiorly and inferiorly, indicated by yellow arrows in both (a) and (b). (d) Thoracolumbar image demonstrating SIEH anteriorly at T9/10 and posteriorly at T10/11. (c) Enlarged field of view (as indicated by the white arrow) over the region of hemorrhage in (d) with dimensions. In all panels, the vertebral levels are labeled. Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SIEH, spontaneous intradural extramedullary hemorrhage.

Figure 2:

Axial MRI of the foramen magnum showing dependent blood products. (a) T1-weighted imaging. (b) T2-weighted imaging. (c) T2-FLAIR sequenced imaging. The yellow arrows indicate the blood products lying in the spinal canal. This was thought to have migrated from another site of bleeding, during our patient’s period of recumbency. MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging, T2-FLAIR: T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery.

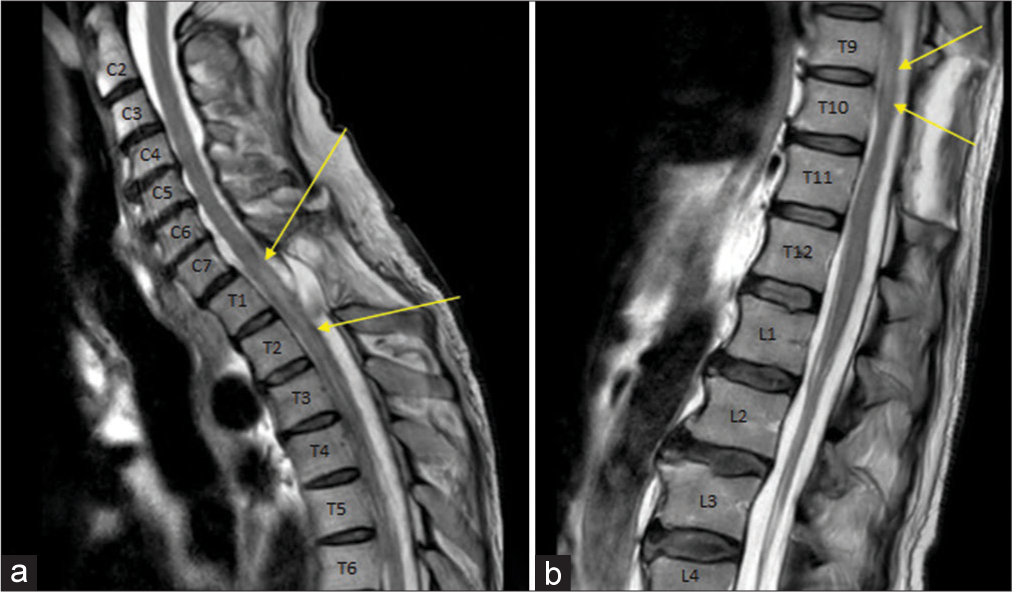

Immediately post-operatively, there was minimal neurological improvement. Our patient’s pain ameliorated but flaccid paraplegia persisted and he was doubly incontinent. His post-operative radiology is depicted in

Figure 3:

Post-operative sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the spine. (a): Cervicothoracic image showing the decompressed spinal cord at T1/2. (b) Thoracolumbar image showing the decompressed spinal cord from T9-11. In both (a) and (b), note the areas of persistent cord signal change, indicated by the yellow arrows. In both panels, the vertebral levels are labeled. MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous SIEH associated with anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet medications, in the absence of an underlying lesion, is extremely rare. The gold standard in the assessment of spinal cord or neural compromise due to SIEH is MRI.[

The pathogenesis of SIEH is not well understood. Previous studies have reported a preponderance of SIEH to occur in the thoracolumbar spine without a gender predominance.[

Surgical and non-surgical treatment strategies have been employed in the treatment of SIEH. The underlying derangement of coagulation should be corrected. Conservative management strategies have been reported in patients with mild or spontaneously improving neurological deficits, although this is uncommon.[

CONCLUSION

Coagulation-impairing medications rarely cause SIEH. Sudden onset back pain associated with acute neurological deficits may represent compressive hemorrhagic spinal pathology. Vascular disease risk factors including atherosclerosis, and hypertension, may be implicated in its pathogenesis. More research is required to support this assertion. The gold standard of imaging in SIEH is MRI. Urgent decompressive surgery should be considered in patients with neurological deficits. Timely decompression confers a more favorable prognosis. More severe neurology (especially motor deficits) at presentation implies a worse recovery.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Bernsen RA, Hoogenraad TU. A spinal haematoma occurring in the subarachnoid as well as in the subdural space in a patient treated with anticoagulants. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1992. 94: 35-7

2. Boukobza M, Haddar D, Boissonet M, Merland JJ. Spinal subdural haematoma: A study of three cases. Clin Radiol. 2001. 56: 475-80

3. Bruce-Brand RA, Colleran GC, Broderick JM, Lui DF, Smith EM, Kavanagh EC. Acute nontraumatic spinal intradural hematoma in a patient on warfarin. J Emerg Med. 2013. 45: 695-7

4. Cha YH, Chi JH, Barbaro NM. Spontaneous spinal subdural hematoma associated with low-molecular-weight heparin. Case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005. 2: 612-3

5. Domenicucci M, Ramieri A, Ciappetta P, Delfini R. Nontraumatic acute spinal subdural hematoma: Report of five cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1999. 91: 65-73

6. Gaitzsch J, Berney J. Spinal subarachnoid hematoma of spontaneous origin and complicating anticoagulation. Report of four cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1984. 21: 534-8

7. Girithari G, Dos Santos IC, Alves T, Claro E, Kirzner M, Massano AL. Spontaneous spinal intradural haematoma in an anticoagulated woman. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2018. 5: 000951

8. Hausmann Kirsch E, Radü E, Mindermann TH, Gratzl O. Coagulopathy induced spinal intradural extramedullary haematoma: Report of three cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2001. 143: 135-40

9. Morandi X, Riffaud L, Chabert E, Brassier G. Acute nontraumatic spinal subdural hematomas in three patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001. 26: E547-51

10. Peñas ML, Guerrero AL, Velasco MR, Herrero S. Spontaneous intradural spinal haematoma associated with a cerebral subarachnoid haemorrhage. Neurologia. 2011. 26: 182-4

11. Wong GR, Scherer DJ, Nelson AJ, Worthley MI. Non-traumatic spinal intradural haematoma: A rare case of paralysis following abciximab for ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2016. 2016: bcr2016215616