- Department of Neurosurgery, Centro Médico Arturo Montiel Rojas, Instituto de Seguridad Social del Estado de México y Municipios, México-Toluca, Metepec,

- Department of Radiology, Centro Médico Arturo Montiel Rojas, Instituto de Seguridad Social del Estado de México y Municipios, México-Toluca, Metepec,

- Department of Neurological Center, ABC Medical Center, Tlaxcala Santa Fe, Mexico.

Correspondence Address:

Julio César Delgado-Arce, Department of Neurosurgery, Centro Médico Arturo Montiel Rojas, Instituto de Seguridad Social del Estado de México y Municipios, México-Toluca, Metepec, Mexico.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_668_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Julio César Delgado-Arce1, Fabiola Alejandra Becerra-Arciniega2, Elizabeth Escamilla-Chávez1, Hector Sebastián VelascoTorres1, Pablo David Guerrero-Suarez1, Jaime Jesús Mártinez-Anda3. Mycotic clival osteomyelitis secondary to immunosuppression by SARS-CoV-2. 07-Oct-2022;13:459

How to cite this URL: Julio César Delgado-Arce1, Fabiola Alejandra Becerra-Arciniega2, Elizabeth Escamilla-Chávez1, Hector Sebastián VelascoTorres1, Pablo David Guerrero-Suarez1, Jaime Jesús Mártinez-Anda3. Mycotic clival osteomyelitis secondary to immunosuppression by SARS-CoV-2. 07-Oct-2022;13:459. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11919/

Abstract

Background: During the past 2 years, the use of systemic corticosteroids has increased due to COVID-19 atypical pneumonia management. Similarly, an increase in mycotic infection cases has been reported during the same period as a consequence of immunosuppression caused by corticosteroid overuse. Mycotic clival osteomyelitis is a rare clinical entity which presumably has increased its incidence during the pandemic.

Case Description: A 52-year-old woman who presented persistent headaches and unexplained weight loss after being hospitalized due to COVID-19 pneumonia treated with intravenous corticosteroids. Head computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging showed extensive osteomyelitis at the clival region with no brain parenchyma involvement. Surgical excision through navigation-guided transnasal transclival endoscopic extended approach was performed for surgical debridement. Histopathological analysis revealed angulated hyphae, suggestive of Aspergillosis. Systemic antifungal treatment was administered for 30 consecutive days. Afterward, she was discharged without any remarkable neurological findings, reassessed during follow-up.

Conclusion: The COVID-19 pandemic has had an effect on the reemergence of mycotic infections due to corticosteroid immunosuppression. Clival osteomyelitis secondary to mycotic infection is an exclusion diagnosis that we encourage to be highly suspected within the persisting COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Aspergillosis, COVID-19, Osteomyelitis

INTRODUCTION

Since the end of 2019, COVID-19 has infected more than 500 million people, with more than 6 million deaths up to date.[

Skull base osteomyelitis (SBO) is a rare, yet potentially treatable disease. Usually, the microorganisms involved are Staphylococcus aureus, and the most prevalent mycotic agent is Aspergillosis fumigatus.[

CLINICAL CASE PRESENTATION

A 52-year-old female with a previous medical history of hypertension in adherence to antihypertensive treatment (thiazide and angiotensin II receptor blocker), type 2 diabetes in adherence to Glargine insulin, and metformin treatment, arrived to the emergency room with ventilatory compromise and hypoxemia. SARS-CoV-2 infection was diagnosed with a positive PCR test, clinically classified as moderate COVID-19 due to fever, dyspnea, and hypoxemia, which required 18 days of hospitalization and management with intravenous corticosteroids (6 mg dexamethasone q. d.) as well as subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin (60 mg enoxaparin q. d.). Hospital discharge was decided after stable and favorable clinical evolution, with prescription of continuous supplementary oxygen (5 L/h), dose adjustment of antidiabetic drugs, with no further required changes or complications.

Two weeks after hospital discharge, she presents a mild headache (visual analog scale 4/10). A month after discharge, she presents malaise and an unexplained weight loss of 8 kg. During follow-up, neurologic examination was unremarkable and there was no further need of supplementary oxygen. Nevertheless, cephalgia and intermittent nasal constipation were the patient’s prevalent symptoms.

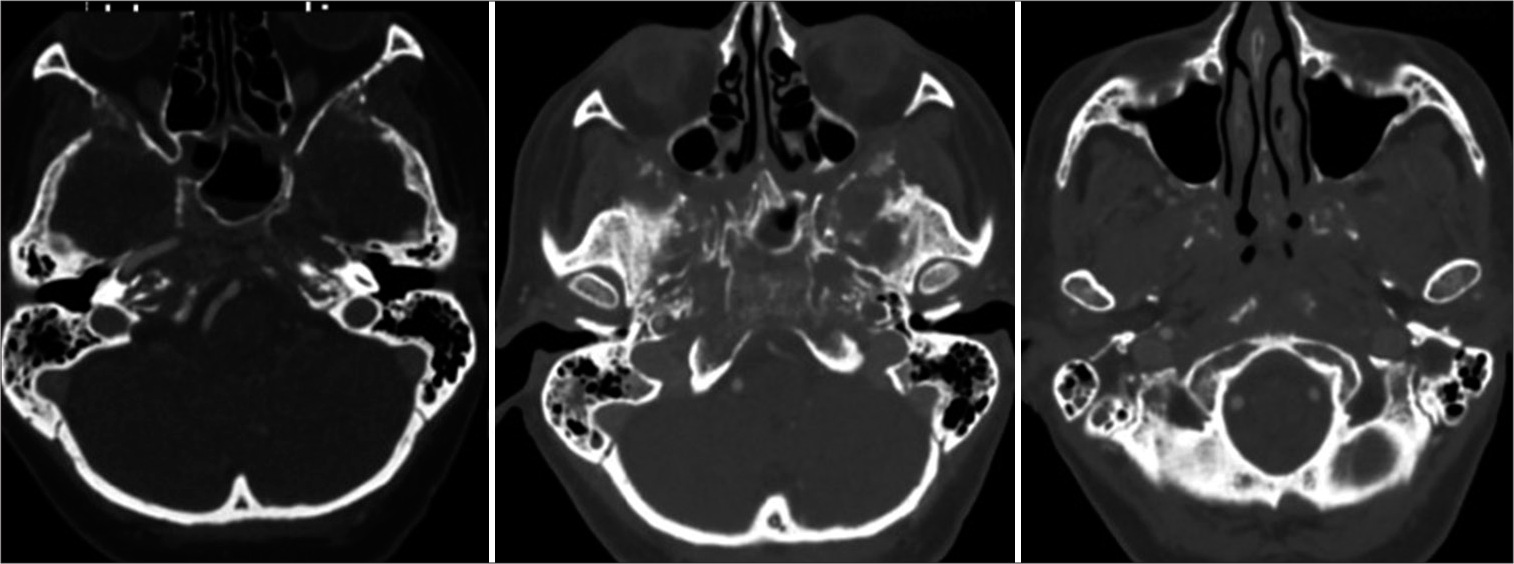

A head computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, which revealed a lesion within the paranasal sinuses. Bone window revealed demineralization with trabecular pattern, and cortical involvement of the walls of the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses, pterygoid processes, turbinate bones, nasal septum, clivus, petrous apex, vomer, carotid foramina, greater wings of the sphenoid bone, frontal processes, orbital processes of frontal bone, and anterior and posterior clinoid processes, [

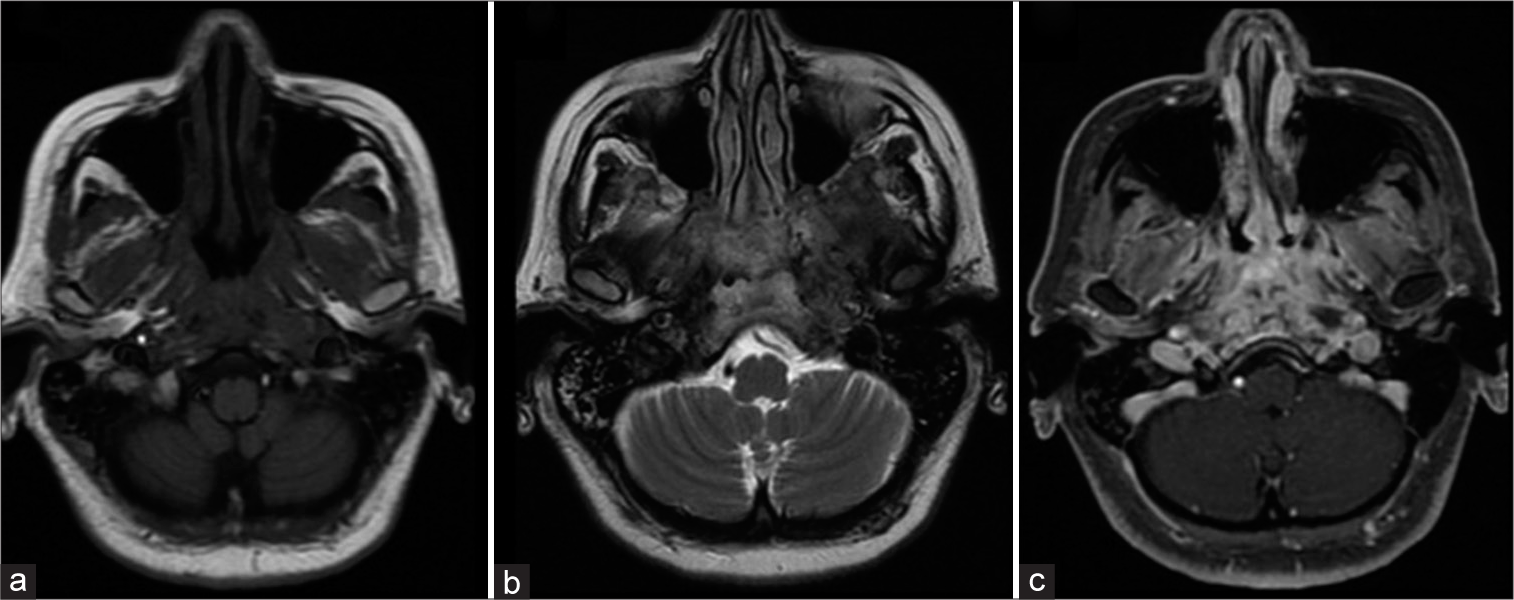

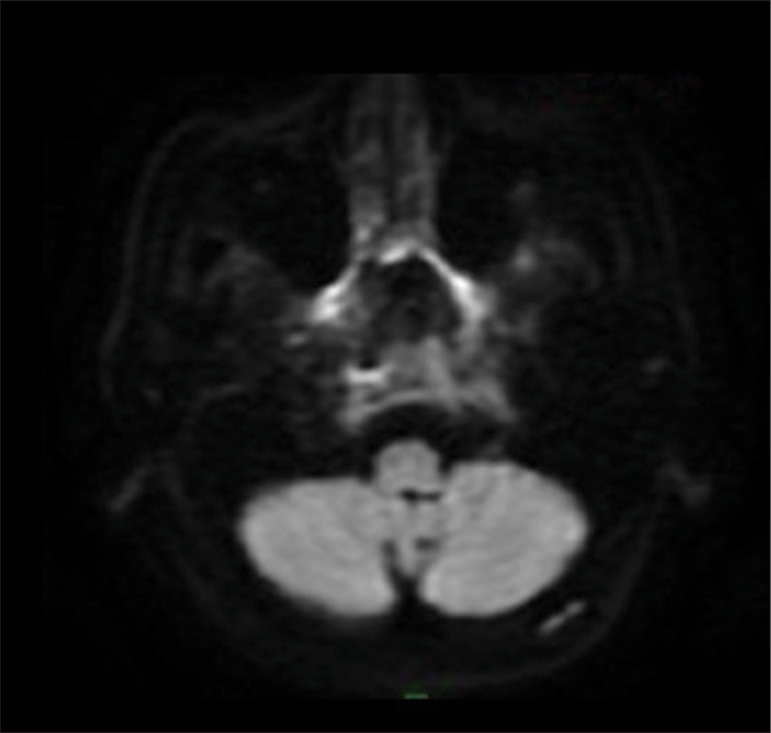

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the skull base at the level of the clivus and the petrous apex showed soft tissues as isointense to muscle tissue in T1-weighted sequence and hyperintense in T2-weighted as well as in fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence, with gadolinium enhancement in fat-saturated contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1+C+FAT) sequence, [

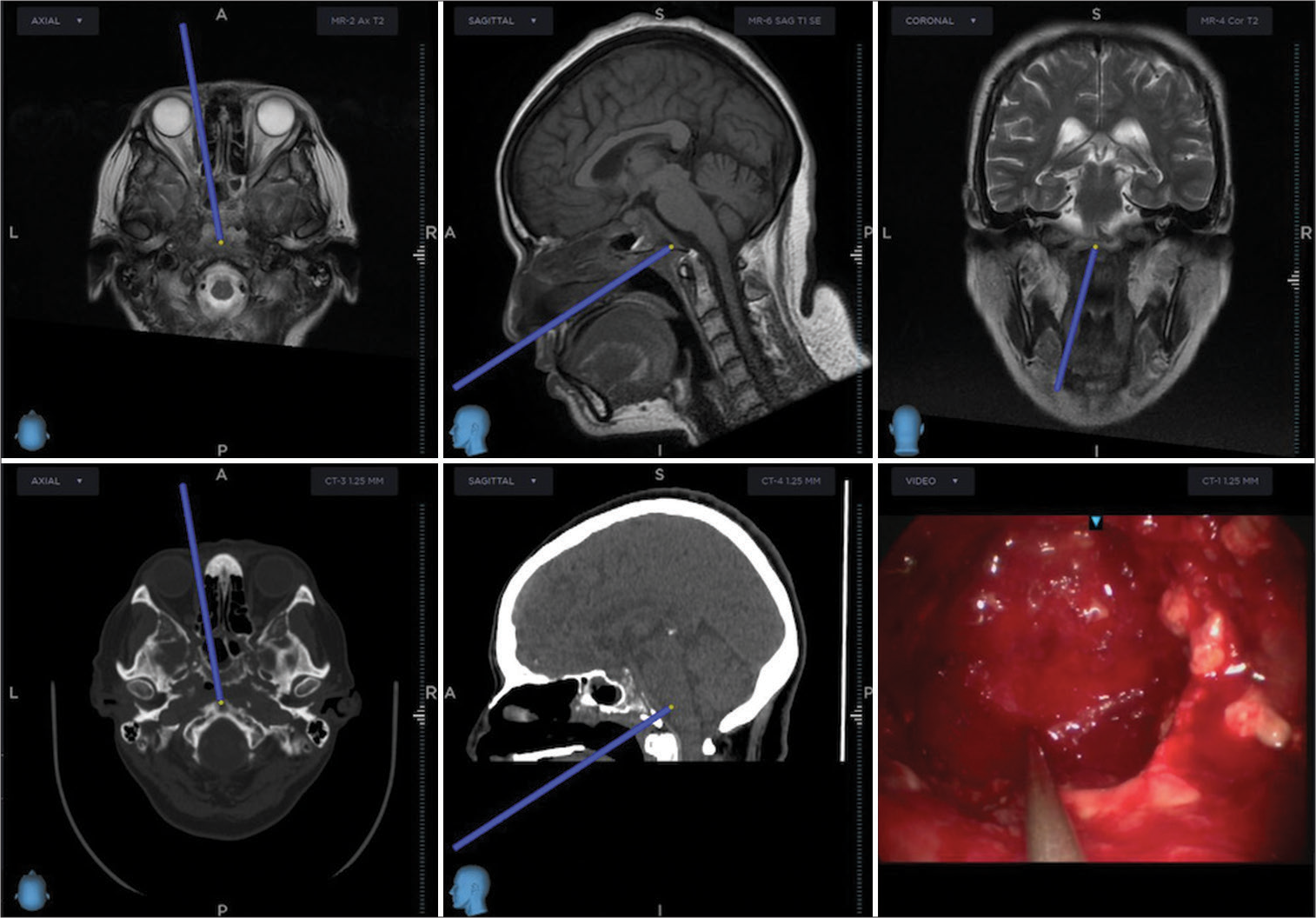

Given the MRI findings, surgical excision through navigation-guided transnasal transclival endoscopic extended approach and later nasoseptal pediculated flap rotation was performed, [

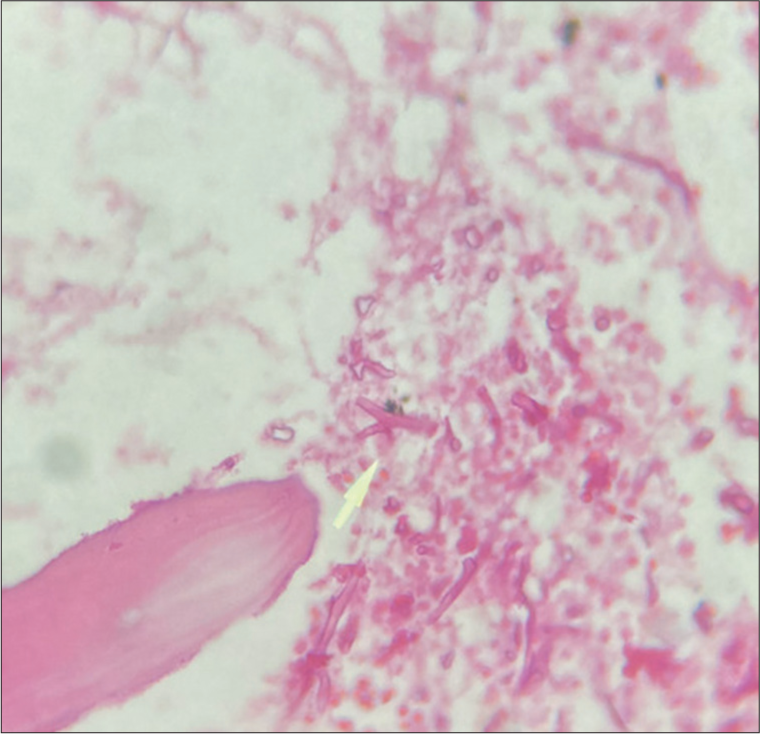

Microbiology and histopathological analysis revealed 90° angled hyphae suspicious of Aspergillosis, [

DISCUSSION

SBO is a rare entity with high risk of mortality, representing both a clinical and imaging diagnostic challenge. There are two categories of skull base osteomyelitis: typical and atypical (or central) osteomyelitis.[

Typical SBO is the most frequent type among these two. Most typical SBO cases present within diabetic and elder population, whose immunocompromise leads to external necrotizing otitis by Pseudomonas infection.[

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, clinical severity has been graded as asymptomatic, symptomatic, ventilatory compromise, severe ventilatory failure, and death. Within the context of COVID-19, bacterial and mycotic secondary infections are a clinical challenge due to its abrupt increase of morbidity and mortality.[

Cephalgia and facial pain are symptoms reported in most SBO cases. However, several cases with cranial nerves affection (VI, IX, X, XI, and XII) have been reported.[

Radio imaging correlation with the clinical presentation is fundamental during the diagnosis approach of SBO. In general, the use of contrasted CT scan and gadolinium-enhanced MRI is fundamental. In complex cases, the use of functional studies may provide us useful bone metabolism data, such as positron emission tomography CT scan with technetium 99.[

When atypical SBO is present, it is important to evaluate key areas including the bony external auditory canal, mastoid process, temporomandibular joint, petrous apex, petro-occipital fissure, foramen lacerum, jugular foramen, and clivus, where most frequently the origin of disease is clival infection.[

CT scan is the gold standard imaging study for SBO. It is a helpful tool to evaluate the extent and severity of infection, as well as to assess cortical bone erosion or trabecular demineralization related to osteomyelitis.[

MRI is complementary for soft-tissue analysis around the skull base and medullary cavity of the bone.[

Nuclear medicine provides both functional and metabolic data of the osseous tissue, complementing for localization of skull base infection. Specifically, technetium 99m-methyl diphosphonate (Tc99m MDP) demonstrates a higher osteoblastic activity whenever an infectious process is present within the bone.[

Surgical debridement and antimycotic treatment are the standard therapy on invasive SBO caused by Aspergillosis.[

CONCLUSION

Clival osteomyelitis secondary to mycotic infection is a rare clinical infectious entity with a challenging diagnosis and treatment approach. It is usually considered an exclusion diagnosis and is finally confirmed with histopathological and microbiological analysis. Within the still present COVID-19 pandemic, we encourage a high suspicion of this entity to be considered in elder, diabetic patients treated with corticosteroids, with atypical signs and symptoms. Surgical debridement is not only vital part of the treatment but also part of the definite diagnosis approach.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledg ments

Translated by Rodrigo Uribe and Jafet García.

References

1. Abou-Al-Shaar H, Mulvaney GG, Alzhrani G, Gozal YM, Oakley GM, Couldwell WT. Nocardial clival osteomyelitis secondary to sphenoid sinusitis: An atypical skull base infection. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2019. 161: 529-34

2. Balakrishnan R, Dalakoti P, Nayak DR, Pujary K, Singh R, Kumar R. Efficacy of HRCT imaging vs SPECT/CT scans in the staging of malignant external otitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019. 161: 336-42

3. Baumann A, Zimmerli S, Häusler R, Caversaccio M. Invasive sphenoidal aspergillosis: Successful treatment with sphenoidotomy and voriconazole. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2007. 69: 121-6

4. Beer-Furlan A, Balsalobre L, Vellutini EA, Stamm AC. Endoscopic endonasal approach in invasive aspergillosis of the clivus in an immunocompetent patient. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2015. 157: 2221-2

5. Chang PC, Fischbein NJ, Holliday RA. Central skull base osteomyelitis in patients without otitis externa: Imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003. 24: 1310-6

6. Chapman PR, Choudhary G, Singhal A. Skull base osteomyelitis: A comprehensive imaging review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2021. 42: 404-13

7. Gothard P, Rogers TR. Voriconazole for serious fungal infections. Int J Clin Pract. 2004. 58: 74-80

8. Grey I, Arora T, Thomas J, Saneh A, Tohme P, Abi-habib R. Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in english and mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID-19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier connectm, the company’s public news and information. Psychiatry Res. 2020. 14: 293

9. Hughes S, Troise O, Donaldson H, Mughal N, Moore LS. Bacterial and fungal coinfection among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study in a UK secondary-care setting. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020. 26: 1395-9

10. John TM, Jacob CN, Kontoyiannis DP. When uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and severe covid-19 converge: The perfect storm for mucormycosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2021. 7: 298

11. Johnson AK, Batra PS. Central skull base osteomyelitis: An emerging clinical entity. Laryngoscope. 2014. 124: 1083-7

12. Kurihara K. Special feature: Statistics for COVID-19 pandemic data. Jpn J Stat Data Sci. 2022. 5: 275-7

13. Lionakis MS, Kontoyiannis DP. Glucocorticoids and invasive fungal infections. Lancet. 2003. 362: 1828-38

14. Michalowicz M, Ramanathan M. Clival osteomyelitis presenting as a skull base mass. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2017. 78: e93-5

15. Nabavizadeh SA, Vossough A, Pollock AN. Clival osteomyelitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013. 29: 1030-2

16. Radhakrishnan S, Mujeeb H, Radhakrishnan C. Central skull base osteomyelitis secondary to invasive aspergillus sphenoid sinusitis presenting with isolated 12th nerve palsy. IDCases. 2020. 22: e00930

17. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021. 384: 693-704

18. Ridder GJ, Breunig C, Kaminsky J, Pfeiffer J. Central skull base osteomyelitis: New insights and implications for diagnosis and treatment. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015. 272: 1269-76

19. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020. 395: 1054-62