- Department of Neurosurgery, Winthrop Neuroscience, Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, New York, USA

Correspondence Address:

Nancy E. Epstein

Department of Neurosurgery, Winthrop Neuroscience, Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, New York, USA

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.182550

Copyright: © 2016 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Epstein NE. Perioperative visual loss following prone spinal surgery: A review. Surg Neurol Int 17-May-2016;7:

How to cite this URL: Epstein NE. Perioperative visual loss following prone spinal surgery: A review. Surg Neurol Int 17-May-2016;7:. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/perioperative-visual-loss-following-prone-spinal-surgery-a-review/

Abstract

Background:Postoperative visual loss (POVL) following prone spine surgery occurs in from 0.013% to 1% of cases and is variously attributed to ischemic optic neuropathy (ION: anterior ION or posterior ION [reported in 1.9/10,000 cases: constitutes 89% of all POVL cases], central retinal artery occlusion [CRAO], central retinal vein occlusion [CRVO], cortical blindness [CB], direct compression [horseshoe, prone pillows, and eye protectors Dupaco Opti-Gard]), and acute angle closure glaucoma (AACG).

Methods:Risk factors for ION include prolonged operative times, long-segment spinal instrumentation, anemia, intraoperative hypotension, diabetes, obesity, male sex, using the Wilson frame, microvascular pathology, decreased the percent of colloid administration, and extensive intraoperative blood loss. Risk factors for CRAO more typically include improper positioning during the surgery (e.g., cervical rotation), while those for CB included prone positioning and obesity.

Results:POVL may be avoided by greater utilization of crystalloids versus colloids, administration of α-2 agonists (e.g., decreases intraocular pressure), avoidance of catecholamines (e.g., avoid vasoconstrictors), avoiding intraoperative hypotension, and averting anemia. Patients with glaucoma or glaucoma suspects may undergo preoperative evaluation by ophthalmologists to determine whether they require prophylactic treatment prior to prone spinal surgery and whether and if prophylactic treatment is warranted.

Conclusions:The best way to avoid POVL is to recognize its multiple etiologies and limit the various risk factors that contribute to this devastating complication of prone spinal surgery. Furthermore, routinely utilizing a 3-pin head holder will completely avoid ophthalmic compression, while maintaining the neck in a neutral posture, largely avoiding the risk of jugular vein and/or carotid artery compromise and thus avoiding increasing IOP.

Keywords: Blindness, central retinal artery occlusion, cortical blindness, eye diseases, glaucoma, ischemic optic neuropathy, prone position, spinal surgery, visual loss

INTRODUCTION

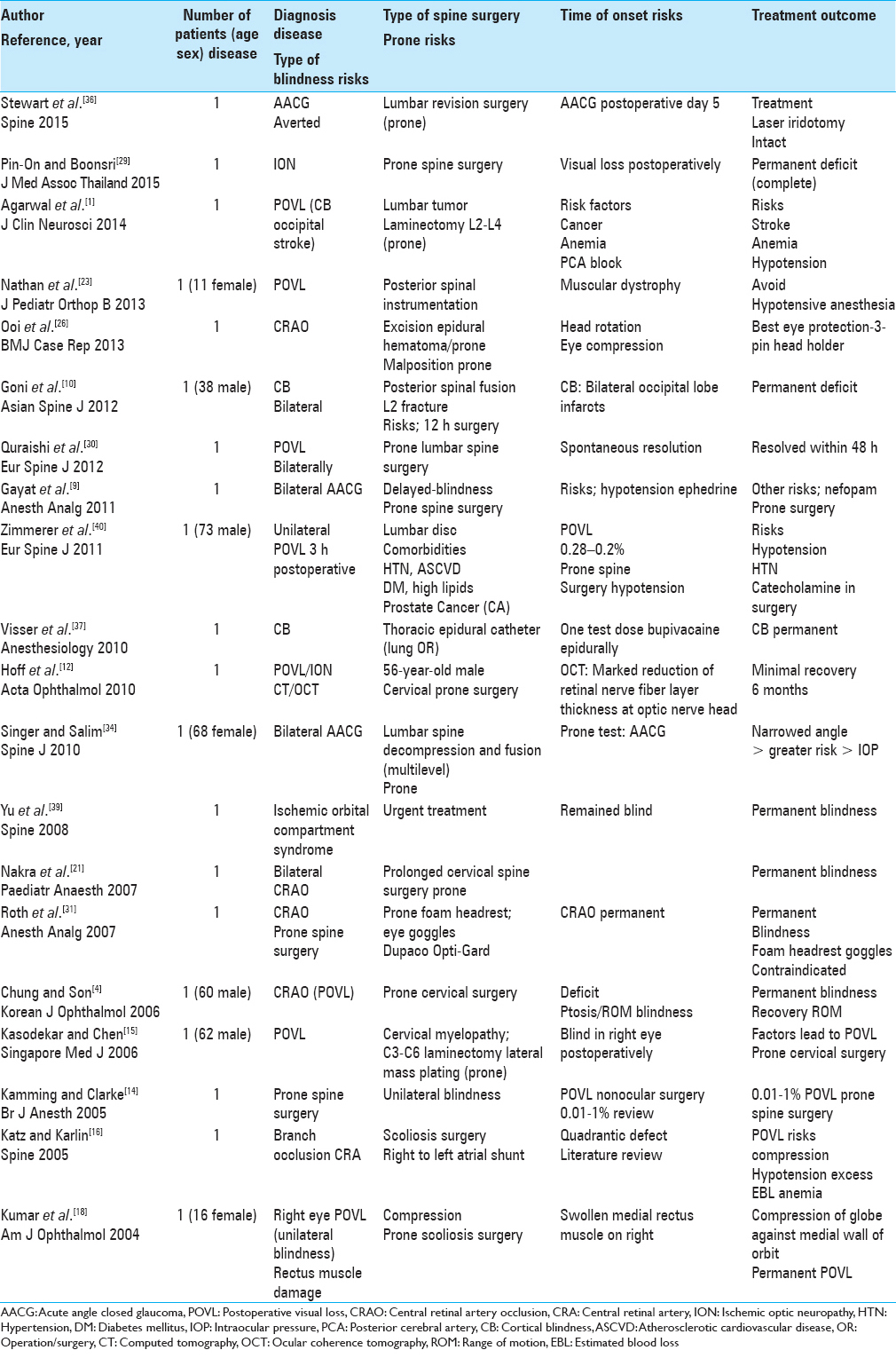

Postoperative visual loss (POVL) following prone spine surgery occurs in from 0.013% to 1% of cases, and the most frequently quoted risk is 0.2% [Tables

The preoperative recognition of risk factors may protect against the development of POVL. The multiple factors contributing to ION may include; prolonged operative times, long-segment spinal instrumentation, anemia, intraoperative hypotension, diabetes, obesity, male sex, the Wilson frame, greater estimated blood loss (EBL), microvascular pathology, and decreased percent colloid administration. Risk factors for CRAO typically include improper positioning during the surgery (e.g., cervical rotation), while those for CB included prone positioning and obesity.

Limiting the risk of POVL may warrant greater utilization of crystalloids versus colloids, administration of α-2 agonists (e.g., decreases intraocular pressure [IOP]), avoidance of catecholamines (e.g., avoid vasoconstrictors), and avoiding excessive intraoperative blood loss/anemia, hypotension, and hypovolemia. Patients at risk for AACG may undergo preoperative ophthalmologic evaluation and prophylactic treatment where indicated. Most critically, routinely utilizing a 3-pin head holder for prone positioning completely avoids ophthalmic compression, and maintains the neck in a neutral posture, avoiding the potential for jugular venous congestion or carotid artery occlusion/embolization/compromise.

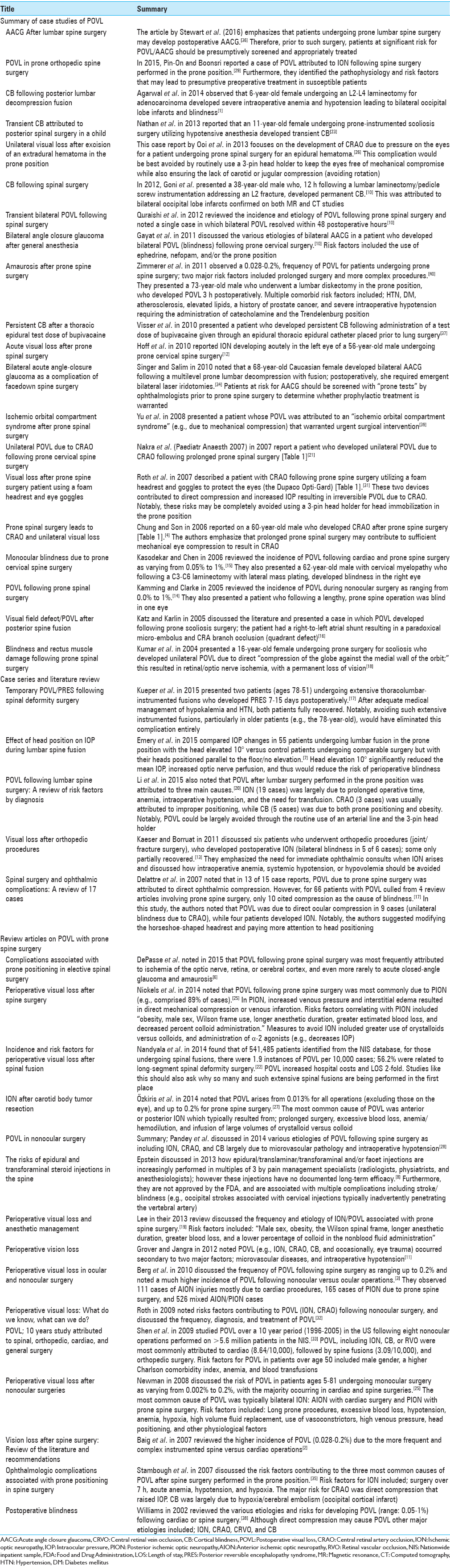

SUMMARY OF CASE STUDIES OF POSTOPERATIVE VISUAL LOSS

Of the 21 single case studies reviewed, the etiology of the POVL included: AACG (three patients), ION (three patients) CB (three patients), CRAO (four patients), ischemic orbital compartment syndrome/compression (one patients), CRA branch occlusion (one patient), or general POVL/unspecified etiology (six patients) [Tables

Acute angle closure glaucoma after lumbar spine surgery

Five days following lumbar surgery performed in the prone position, Stewart et al. (2016) presented a patient who developed AACG due to an acute increase in IOP that had occurred intraoperatively [Tables

Postoperative visual loss in prone orthopedic spine surgery

Pin-On and Boonsri in 2015 reported on a patient with POVL due to ION occurring during prone spinal surgery [Tables

Cortical blindness following posterior lumbar decompression fusion

Agarwal et al. in 2014 noted that a 60-year-old paraparetic female developed POVL following an L2–L4 laminectomy for partial resection of a metastatic adenocarcinoma [Tables

Transient cortical blindness attributed to posterior spinal surgery in a child

Nathan et al. in 2013 noted the multiple factors that contribute to POVL following prone spine surgery; these vary from direct ocular ischemia (compression/venous occlusion) to CRAO, ION, or occipital cortical ischemia (infarction) [

Unilateral visual loss after excision of an extradural hematoma in the prone position

Ooi et al. in 2013 presented a patient who developed blindness attributed to CRAO following excision of an epidural spinal hematoma performed in the prone position [Tables

Cortical blindness following spinal surgery

In Goni et al. study in 2012, a 38-year-old male undergoing a laminectomy with pedicle screw instrumentation for an L2 fracture developed bilateral CB attributed to occipital lobe infarcts (computed tomography and magnetic resonance confirmed) within 12 h of surgery [Tables

Transient bilateral postoperative visual loss following spinal surgery

Quraishi et al. in 2012 reviewed the general incidence and etiology of POVL following prone spinal surgery while also presenting one case of bilateral POVL that resolved within 48 postoperative hours [Tables

Bilateral angle closure glaucoma after general anesthesia

Gayat et al. in 2011 discussed a patient who developed POVL attributed to bilateral postoperative AACG following prone cervical spine surgery [Tables

Amaurosis after prone spine surgery

Zimmerer et al. in 2011 discussed the 0.028–0.2% frequency of POVL following prone spine surgery [Tables

Persistent cortical blindness after a thoracic epidural test dose of bupivacaine

Visser et al. in 2010 observed that following administration of a test dose of bupivacaine for thoracic epidural anesthesia (e.g., administered through an epidural catheter) in a patient about to undergo lung surgery, the patient developed persistent CB [Tables

Acute visual loss after prone spinal surgery

Hoff et al. in 2010 reported acute left-eye ION in a 56-year-old male undergoing prone cervical spine surgery [Tables

Bilateral acute angle closure glaucoma as a complication of facedown spine surgery

Singer and Salim in 2010 reported that prone spine surgery increased IOP “in individuals susceptible to AACG” [Tables

Ischemic orbital compartment syndrome after prone spinal surgery

Yu et al. in 2008 presented a patient undergoing prone spine surgery who developed “ischemic orbital compartment syndrome (e.g., due to compression)” warranting urgent intervention [Tables

Unilateral postoperative visual loss due to the central retinal artery occlusion following prone cervical spine surgery

Nakra et al. in 2007 reported a patient who developed unilateral POVL due to CRAO following prolonged spine surgery performed in the prone position [Tables

Visual loss after prone spine surgery in patient using a foam headrest and eye goggles

Roth et al. 2007 described a patient who developed CRAO following prone spine surgery utilizing a foam headrest and goggles to protect the eyes (the Dupaco Opti-Gard) [Tables

Prone spinal surgery leads to central retinal retinal artery occlusion and unilateral visual loss

Chung and Son in 2006 reported on a 60-year-old male who developed CRAO after prone spine surgery [Tables

Monocular blindness due to prone cervical spine surgery

Kasodekar and Chen in 2006 documented a 0.05–1% risk of POVL with cardiac or prone spine (including prone cervical spine) surgery [Tables

Postoperative visual loss following prone spinal surgery

Kamming and Clarke in 2005 identified the incidence of POVL during nonocular surgery as ranging from 0.01% to 1% [Tables

Visual field defect/postoperative visual loss after posterior spine fusion

Katz and Karlin in 2005 reviewed the literature and presented a case in which POVL followed prone scoliosis surgery [Tables

Blindness and rectus muscle damage following prone spinal surgery

Kumar et al. in 2004 discussed a 16-year-old female who following prone surgery for scoliosis, developed ocular compression responsible for both POVL and rectus muscle damage [Tables

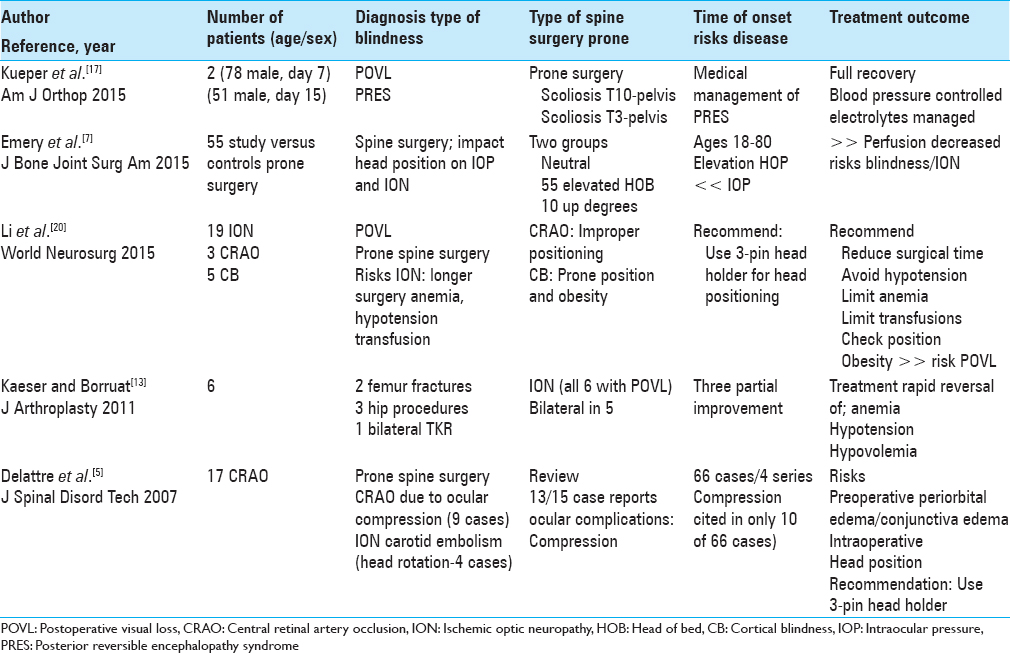

CASE SERIES AND LITERATURE REVIEW

The five case series involving between 2 and 55 patients per study, and recounted the multiple etiologies of POVL attributed to prone spine surgery [Tables

Temporary postoperative visual loss/posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome following spinal deformity surgery

Kueper et al. in 2015 evaluated two patients presenting with PRES contributing to temporary POVL following prone spinal deformity surgery [Tables

Effect of head position on intraocular pressure during lumbar spine fusion

Emery et al. in 2015 noted that ION resulted from decreased perfusion attributed to increased IOP and/or hypotension occurring during prone spinal surgery [Tables

Postoperative visual loss following lumbar spine surgery: A review of risk factors by diagnosis

Li et al. in 2015 also noted that POVL rarely occurs following lumbar spine surgery performed in the prone position [Tables

Visual loss after orthopedic procedures

Kaeser and Borruat in 2011 discussed six patients who developed ION (five of six cases bilateral blindness) following various orthopedic procedures (joint/fracture surgery); for some patients, deficits only partially recovered [Tables

Spinal surgery and ophthalmic complications: A review of 17 cases

Delattre et al. in 2007 noted that in 13 of 15 case reports, POVL due to prone spine surgery were due to ophthalmic compression [Tables

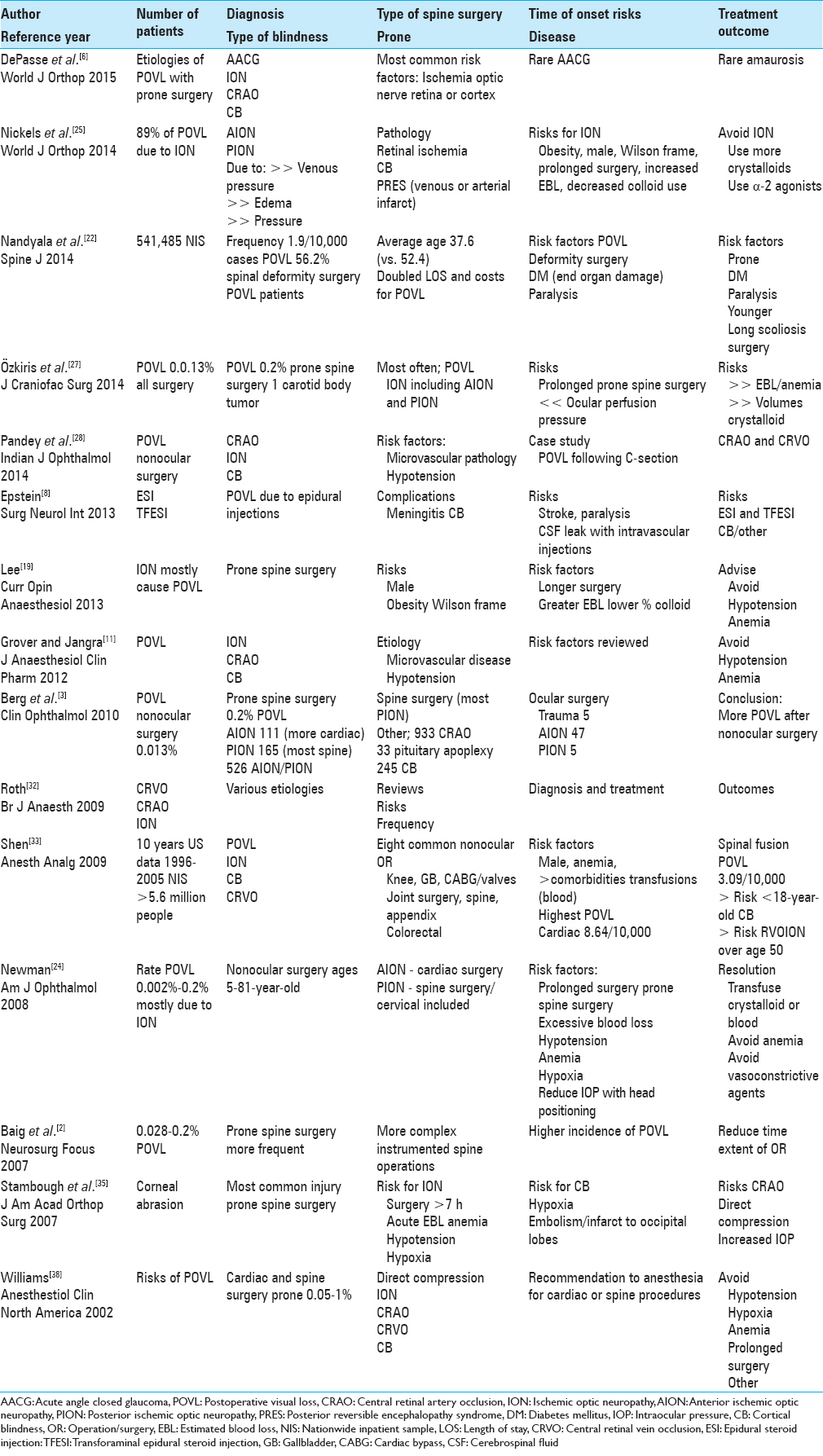

REVIEW ARTICLES ON POSTOPERATIVE VISUAL LOSS WITH PRONE SPINE SURGERY

The 15 review articles from 2004 to 2015 cited the various types of POVL; ION (AION/PION), CRAO (including CRA-branch occlusion), CRVO, AACG, and CB (occipital lobe infarcts) [Tables

Complications associated with prone positioning in elective spinal surgery

DePasse et al. in 2015 noted that POVL following prone spinal surgery was most frequently attributed to ischemia of the optic nerve, retina, or cerebral cortex, and rarely, AACG and amaurosis [Tables

Perioperative visual loss after spine surgery

Nickels et al. in 2014 evaluated POVL attributed to either prone spine or cardiac surgery [Tables

Incidence and risk factors for perioperative visual loss after spinal fusion

Nandyala et al. in 2014 found that POVL was a rare complication of prone spine fusion surgery [Tables

Ischemic optic neuropathy after carotid body tumor resection

Özkiris et al. in 2014 noted that POVL followed any surgery in 0.013% of cases, but up to 0.2% of spine operations performed in the prone position [Tables

Postoperative visual loss in nonocular surgery

Pandey et al. discussed in 2014 various etiologies of POVL following prone spine surgery; this included ION, CRAO or branch retinal artery occlusion, and CB largely due to microvascular pathology and/or intraoperative hypotension [Tables

The risks of epidural and transforaminal steroid injections in the spine

Epstein discussed in 2013 how the various types of spinal injections (e.g., epidural/translaminar, transforaminal, or facet injections) are increasingly and typically unnecessarily being performed in multiples of three by pain management specialists (radiologists, physiatrists, and anesthesiologists) [Tables

Perioperative visual loss and anesthetic management

Lee in their 2013 review discussed the frequency of ION/POVL due to prone spine surgery [Tables

Perioperative vision loss

Grover and Jangra in 2012 noted POVL occurred following prone spine surgery and cardiothoracic surgical procedures; it was variously attributed to ION, CRAO, CB, and occasionally, compressive ocular trauma [Tables

Perioperative visual loss in ocular and nonocular surgery

Berg et al. in 2010 discussed the frequency of POVL following nonocular surgery as ranging from 0.013% for all operations, but up to 0.2% following spine surgery [Tables

Perioperative visual loss: What do we know, what can we do?

Roth in 2009 noted that POVL rarely occurred following nonocular surgery. Its various etiologies included; retinal vascular occlusion (RVO) and ION [Tables

Postoperative visual loss; 10-year study attributed to spinal, orthopedic, cardiac, and general surgery

Shen et al. in 2009 studied POVL over a 10-year period (1996–2005) in the US following eight nonocular operations performed on >5.6 million patients in the NIS [Tables

Perioperative visual loss after nonocular surgeries

Newman in 2008 discussed the risk of POVL in patients ages 5–81 undergoing nonocular surgery as varying from 0.002% to 0.2%; the majority occurred in cardiac and spine surgeries [Tables

Vision loss after spine surgery: review of the literature and recommendations

Baig et al. in 2007 reviewed the higher incidence of POVL (0.028–0.2%) due to the more frequent and complex instrumented spine versus cardiac operations [Tables

Ophthalmologic complications associated with prone positioning in spine surgery

Stambough et al. in 2007 discussed the most common eye injury occurring during prone spine surgery: a corneal abrasion [Tables

Postoperative blindness

Williams in 2002 looked at the various etiologies and of POVL (frequency 0.05–1%) that followed anesthesia for largely cardiac bypass or spine surgery [Tables

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Agarwal N, Hansberry DR, Goldstein IM. Cortical blindness following posterior lumbar decompression and fusion. J Clin Neurosci. 2014. 21: 155-9

2. Baig MN, Lubow M, Immesoete P, Bergese SD, Hamdy EA, Mendel E. Vision loss after spine surgery: Review of the literature and recommendations. Neurosurg Focus. 2007. 23: E15-

3. Berg KT, Harrison AR, Lee MS. Perioperative visual loss in ocular and nonocular surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010. 4: 531-46

4. Chung MS, Son JH. Visual loss in one eye after spinal surgery. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2006. 20: 139-42

5. Delattre O, Thoreux P, Liverneaux P, Merle H, Court C, Gottin M. Spinal surgery and ophthalmic complications: A French survey with review of 17 cases. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007. 20: 302-7

6. DePasse JM, Palumbo MA, Haque M, Eberson CP, Daniels AH. Complications associated with prone positioning in elective spinal surgery. World J Orthop. 2015. 6: 351-9

7. Emery SE, Daffner SD, France JC, Ellison M, Grose BW, Hobbs GR. Effect of head position on intraocular pressure during lumbar spine fusion: A randomized, prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015. 97: 1817-23

8. Epstein NE. The risks of epidural and transforaminal steroid injections in the spine: Commentary and a comprehensive review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2013. 4: S74-93

9. Gayat E, Gabison E, Devys JM. Case report: Bilateral angle closure glaucoma after general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2011. 112: 126-8

10. Goni V, Tripathy SK, Goyal T, Tamuk T, Panda BB, Bk S. Cortical blindness following spinal surgery: Very rare cause of perioperative vision loss. Asian Spine J. 2012. 6: 287-90

11. Grover V, Jangra K. Perioperative vision loss: A complication to watch out. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012. 28: 11-6

12. Hoff JM, Varhaug P, Midelfart A, Lund-Johansen M. Acute visual loss after spinal surgery. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010. 88: 490-2

13. Kaeser PF, Borruat FX. Visual loss after orthopedic procedures. J Arthroplasty. 2011. 26: 338.e17-9

14. Kamming D, Clarke S. Postoperative visual loss following prone spinal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2005. 95: 257-60

15. Kasodekar VB, Chen JL. Monocular blindness: A complication of intraoperative positioning in posterior cervical spine surgery. Singapore Med J. 2006. 47: 631-3

16. Katz DA, Karlin LI. Visual field defect after posterior spine fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005. 30: E83-5

17. Kueper J, Loftus ML, Boachie-Adjei O, Lebl D. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: Temporary visual loss after spinal deformity surgery. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2015. 44: E465-8

18. Kumar N, Jivan S, Topping N, Morrell AJ. Blindness and rectus muscle damage following spinal surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004. 138: 889-91

19. Lee LA. Perioperative visual loss and anesthetic management. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2013. 26: 375-81

20. Li A, Swinney C, Veeravagu A, Bhatti I, Ratliff J. Postoperative visual loss following lumbar spine surgery: A review of risk factors by diagnosis. World Neurosurg. 2015. 84: 2010-21

21. Nakra D, Bala I, Pratap M. Unilateral postoperative visual loss due to central retinal artery occlusion following cervical spine surgery in prone position. Paediatr Anaesth. 2007. 17: 805-8

22. Nandyala SV, Marquez-Lara A, Fineberg SJ, Singh R, Singh K. Incidence and risk factors for perioperative visual loss after spinal fusion. Spine J. 2014. 14: 1866-72

23. Nathan ST, Jain V, Lykissas MG, Crawford AH, West CE. Transient cortical blindness as a complication of posterior spinal surgery in a pediatric patient. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2013. 22: 416-9

24. Newman NJ. Perioperative visual loss after nonocular surgeries. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008. 145: 604-10

25. Nickels TJ, Manlapaz MR, Farag E. Perioperative visual loss after spine surgery. World J Orthop. 2014. 5: 100-6

26. Ooi EI, Ahem A, Zahidin AZ, Bastion ML. Unilateral visual loss after spine surgery in the prone position for extradural haematoma in a healthy young man. BMJ Case Rep 2013. 2013. p.

27. Özkiris M, Akin I, Özkiris A, Adam M, Saydam L. Ischemic optic neuropathy after carotid body tumor resection. J Craniofac Surg. 2014. 25: e58-61

28. Pandey N, Chandrakar AK, Garg ML. Perioperative visual loss with non-ocular surgery: Case report and review of literature. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014. 62: 503-5

29. Pin-On P, Boonsri S. Postoperative visual loss in orthopedic spine surgery in the prone position: A case report. J Med Assoc Thai. 2015. 98: 320-4

30. Quraishi NA, Wolinsky JP, Gokaslan ZL. Transient bilateral post-operative visual loss in spinal surgery. Eur Spine J. 2012. 21: S495-8

31. Roth S, Tung A, Ksiazek S. Visual loss in a prone-positioned spine surgery patient with the head on a foam headrest and goggles covering the eyes: An old complication with a new mechanism. Anesth Analg. 2007. 104: 1185-7

32. Roth S. Perioperative visual loss: What do we know, what can we do?. Br J Anaesth. 2009. 103: i31-40

33. Shen Y, Drum M, Roth S. The prevalence of perioperative visual loss in the United States: A 10-year study from 1996 to 2005 of spinal, orthopedic, cardiac, and general surgery. Anesth Analg. 2009. 109: 1534-45

34. Singer MS, Salim S. Bilateral acute angle-closure glaucoma as a complication of facedown spine surgery. Spine J. 2010. 10: e7-9

35. Stambough JL, Dolan D, Werner R, Godfrey E. Ophthalmologic complications associated with prone positioning in spine surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007. 15: 156-65

36. Stewart RJ, Landy DC, Lee MJ. Unilateral acute angle-closure glaucoma after lumbar spine surgery: A case report and systematic review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016. 41: E297-9

37. Visser WA, Kolling JB, Groen GJ, Tetteroo E, van Dijl R, Rosseel PM. Persistent cortical blindness after a thoracic epidural test dose of bupivacaine. Anesthesiology. 2010. 112: 493-5

38. Williams EL. Postoperative blindness. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2002. 20: 605-22

39. Yu YH, Chen WJ, Chen LH, Chen WC. Ischemic orbital compartment syndrome after posterior spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008. 33: E569-72

40. Zimmerer S, Koehler M, Turtschi S, Palmowski-Wolfe A, Girard T. Amaurosis after spine surgery: Survey of the literature and discussion of one case. Eur Spine J. 2011. 20: 171-6