- Department of Neurosurgery, Lisie Hospital, Ernakulam, Kerala, India

- Department of Neurosurgery, KIMS Hospital, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India

- Department of Medicine, University of Toledo, Toledo, United States

- Department of Neurosurgery, Trivandrum Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India

Correspondence Address:

Biji Bahuleyan, Department of Neurosurgery, Lisie Hospital, Ernakulam, Kerala, India.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_586_2024

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Biji Bahuleyan1, Vineetkumar Thakorbhai Patel2, Mariette Anto1, Sarah E. Hessel3, Rochan K. Ramesh3, K. M. Girish4, Santhosh George Thomas1. Posterior location of the facial nerve on vestibular schwannoma: Report of a rare case and a literature review. 27-Sep-2024;15:345

How to cite this URL: Biji Bahuleyan1, Vineetkumar Thakorbhai Patel2, Mariette Anto1, Sarah E. Hessel3, Rochan K. Ramesh3, K. M. Girish4, Santhosh George Thomas1. Posterior location of the facial nerve on vestibular schwannoma: Report of a rare case and a literature review. 27-Sep-2024;15:345. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=13121

Abstract

Background: Posterior location of the facial nerve in relation to vestibular schwannoma (VS) is extremely rare.

Case Description: An elderly man presented with the right cerebellopontine angle (CPA) syndrome. Magnetic resonance imaging showed the partly cystic and partly solid right CPA lesion extending to the internal auditory meatus. Seventh nerve monitoring showed the facial nerve on the posterior surface of the tumor. At surgery, the facial nerve was seen on the posterior surface of the tumor under the microscope. Partial excision of the tumor was done with preservation of the facial nerve both anatomically and electrophysiologically.

Conclusion: The posterior location of the facial nerve should be anticipated in all patients with VS. The surgical strategy must be altered appropriately to preserve the facial nerve.

Keywords: Dorsal, Facial nerve, Posterior, Tumor, Vestibular schwannoma

INTRODUCTION

The most common location of the facial nerve on the surface of a vestibular schwannoma (VS) is ventral.[

CASE REPORT

A 66-year-old man presented with ataxia, intermittent vertigo, and projectile vomiting of 1-month duration. He had decreased hearing in the left ear for 1 year. His psychiatric history was significant for phobia. On examination, he had a left lower motor neuron type facial paresis (House and Brackmann grade II), decreased hearing on the left side and positive left cerebellar signs. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed a left cerebellopontine angle lesion of size 3 × 2.3 × 1.8 cm, which was partly solid and partly cystic with extension into the internal auditory meatus (IAM) [

Figure 1:

(a) T2-weighted axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) image showing a partly solid and partly cystic cerebellopontine angle (CPA) lesion (white arrow) extending to the left internal auditory meatus (IAM) and (b) Contrast-enhanced axial MRI image showing a partly solid and partly cystic CPA lesion (white arrow) extending to the left IAM. The solid component of the lesion is seen enhancing with contrast.

Before beginning tumor resection, stimulation of the posterior surface of the tumor demonstrated good electromyography responses from all three electrodes (frontalis, orbicularis oculi, and orbicularis oris). The stimulation was repeated with different current strengths. All stimuli gave excellent responses. Even though the facial nerve was not visible at first look, its visibility became better under high magnification of the microscope. The nerve was located on the posterior surface of the tumor at its center, extending between the IAM laterally and the brainstem medially. The features that helped to identify the facial nerve clearly under high magnification were the following (i) the color of the nerve, which was different from that of the tumor, (ii) a thin subarachnoid space was identified on the superior and inferior border of the nerve all along its course as the arachnoid layer extended between the tumor and the facial nerve, and (iii) the vasa nervorum of the facial nerve was seen running parallel to its course as opposed to the haphazard course of the tumor vessels on the tumor surface [

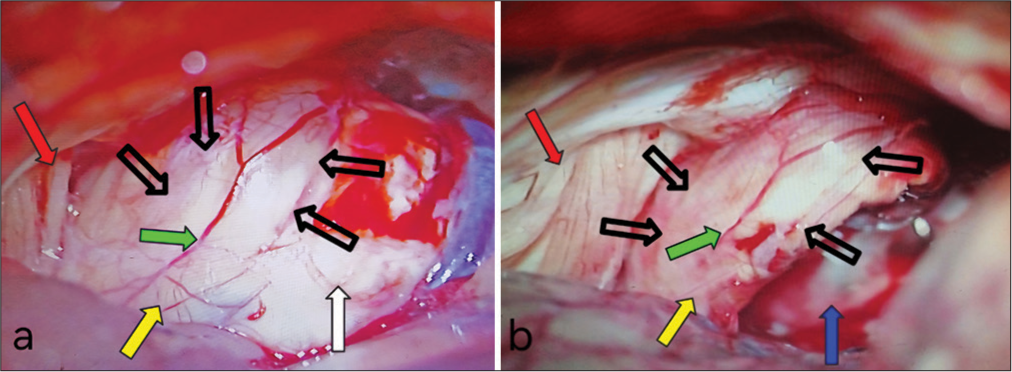

Figure 2:

(a) Intraoperative images before resection of the tumor showing the tumor (white arrow), facial nerve (yellow arrow) on the posterior surface of the tumor, the vasa nervorum on the facial nerve (green arrow), the thin subarachnoid space (empty black arrows) identified along the superior and inferior borders of the facial nerve, and the ninth-tenth nerve complex (red arrow), and (b) Intraoperative images after resection of the tumor showing the facial nerve (yellow arrow) on the posterior surface of the tumor, the vasa nervorum on the facial nerve (green arrow), the thin subarachnoid space (empty black arrows) identified along the superior and inferior borders of the facial nerve, the ninth-tenth nerve complex (red arrow), and the resection cavity (blue arrow).

The surgical strategy was to preserve the facial nerve and partial removal of the tumor, as the patient and his caregivers did not want postoperative facial nerve palsy, given his psychiatric history. Tumor was debulked from its superior and inferior poles until the ventral arachnoid was seen, sparing the facial nerve, retaining a small sheet of tumor on the ventral surface of the nerve. We then gently removed the center and the venteroanterior aspect of the tumor that was located ventral to the facial nerve and hidden by it with the aid of curved instruments. During this portion of the tumor removal, we made sure that no traction was applied to the nerve and the facial nerve integrity was confirmed with intermittent facial nerve stimulation. No attempt was made to remove the tumor from the IAM or the portion of the tumor that was stuck to the immediate ventral surface of the facial nerve. A computed tomography scan done postoperatively showed partial excision of the tumor.

DISCUSSION

The ideal treatment of large VS remains controversial.[

Cystic VS is generally larger and grows more rapidly than solid VS.[

Facial nerve preservation is a vital step in the resection of these tumors.[

VS commonly arises from the superior vestibular nerve and rarely from the inferior vestibular nerve, and it is difficult to determine its nerve of origin.[

Relation of the facial nerve on the surface of tumor

Normally, in the IAM, the facial nerve is located in the anterosuperior quadrant, the superior vestibular nerve in the posterosuperior quadrant, the inferior vestibular nerve in the posteroinferior quadrant, and the cochlear nerve in the anteroinferior quadrant.[

Sampath et al.[

Posterior location of the facial nerve

Sampath et al.[

Reviewing the literature, we could identify only one article that illustrates the posterior location of the facial nerve on the surface of VS.[

Sameshima et al.[

CONCLUSION

This case reiterates the fact that even though rare, surgeons should anticipate the posterior location of the facial nerve on the surface of VS. Electrophysiological stimulation of the posterior surface of the tumor should be done before tumor resection in all cases to look for the facial nerve. In the case of electrophysiology indicating posterior location of the FN, careful inspection of the posterior surface of the tumor should be completed under high magnification with microscopy. Careful microsurgical dissection should be done to achieve maximal cytoreduction of the tumor, preserving the facial nerve. If the nerve is seen in the center of the tumor, as seen in our case, the tumor should be approached superior and inferior to the nerve.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Bae CW, Cho YH, Hong SH, Kim JH, Lee J, Kim CJ. The anatomical location and course of the facial nerve in vestibular schwannomas : A study of 163 surgically treated cases. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2007. 42: 450-54

2. Choi KS, Kim MS, Kwon HG, Jang SH, Kim OL. Preoperative identification of facial nerve in vestibular schwannomas surgery using diffusion tensor tractography. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014. 56: 11-5

3. Gerganov VM, Giordano M, Samii M, Samii A. Diffusion tensor imaging-based fiber tracking for prediction of the position of the facial nerve in relation to large vestibular schwannomas. J Neurosurg. 2011. 115: 1087-93

4. Han JH, Baek KH, Lee YW, Hur YK, Kim HJ, Moon IS. Comparison of clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes of cystic and solid vestibular schwannomas. Otol Neurotol. 2018. 39: e381-6

5. Jung GS, Duarte JF, de Aragão AH, Vosgerau RP, Ramina R. Dorsal displacement of the facial nerve in vestibular schwannoma surgery. Neurosurg Focus Video. 2021. 5: V9

6. Mastronardi L, Fukushima T, Campione A, editors. Advances in vestibular schwannoma microneurosurgery: Improving results with new technologies. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p.

7. Nejo T, Kohno M, Nagata O, Sora S, Sato H. Dorsal displacement of the facial nerve in acoustic neuroma surgery: Clinical features and surgical outcomes of 21 consecutive dorsal pattern cases. Neurosurg Rev. 2016. 39: 277-88 discussion 288

8. Sameshima T, Morita A, Tanikawa R, Fukushima T, Friedman A, Zenga F. Evaluation of variation in the course of the facial nerve, nerve adhesion to tumors, and postoperative facial palsy in acoustic neuroma. J Neurol Surg Part B Skull Base. 2012. 74: 39-43

9. Samii M, Gerganov VM, Samii A. Functional outcome after complete surgical removal of giant vestibular schwannomas: Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2010. 112: 860-7

10. Sampath P, Rini D, Long DM. Microanatomical variations in the cerebellopontine angle associated with vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): A retrospective study of 1006 consecutive cases. J Neurosurg. 2000. 92: 70-8

11. Sartoretti-Schefer S, Kollias S, Valavanis A. Spatial relationship between vestibular schwannoma and facial nerve on three-dimensional t2-weighted fast spin-echo MR images. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000. 21: 810-6

12. Starnoni D, Giammattei L, Cossu G, Link MJ, Roche PH, Chacko AG. Surgical management for large vestibular schwannomas: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and consensus statement on behalf of the EANS skull base section. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020. 162: 2595-617

13. Taoka T, Hirabayashi H, Nakagawa H, Sakamoto M, Myochin K, Hirohashi S. Displacement of the facial nerve course by vestibular schwannoma: Preoperative visualization using diffusion tensor tractography. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006. 24: 1005-10

14. Zhang Z, Nguyen Y, Seta DD, Russo FY, Rey A, Kalamarides M. Surgical treatment of sporadic vestibular schwannoma in a series of 1006 patients. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2016. 36: 408-14