- Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA

- Department of Neurology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA

Correspondence Address:

Nikhil Sharma

Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA

DOI:10.4103/sni.sni_484_17

Copyright: © 2018 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Nikhil Sharma, Frederick L. Hitti, Grant Liu, M. Sean Grady. Pseudotumor cerebri comorbid with meningioma: A review and case series. 04-Jul-2018;9:130

How to cite this URL: Nikhil Sharma, Frederick L. Hitti, Grant Liu, M. Sean Grady. Pseudotumor cerebri comorbid with meningioma: A review and case series. 04-Jul-2018;9:130. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/pseudotumor-cerebri-comorbid-with-meningioma-a-review-and-case-series/

Abstract

Background:Pseudotumor cerebri (PTC), which has a prevalence in the general population of 1 to 2 out of 100,000, presents with raised intracranial pressure (ICP) but generally lacks a space occupying lesion.

Case Description:Patient 1 is a 32-year-old woman with a history of multiple meningiomas. Upon presentation to our institution, her clinical exam was notable for a right sixth nerve palsy. An integrated diagnosis of PTC was made and shunting for the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion was recommended. Approximately 6 weeks after surgery, the patient exhibited complete symptom resolution and discontinued all medications. Patient 2 is a 40-year-old woman with history of meningioma causing partial obstruction of the right transverse sigmoid sinus. She agreed to undergo surgery for the left ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt placement, for management of her PTC. Postoperatively, the patient reported that her vision significantly improved. Patient 3 is a 49-year-old woman with history of meningioma who presented with left visual field cut. A right frontal VP shunt was recommended for the treatment of PTC. Postoperatively, the patient reported significant symptom improvement and resolution of visual complaints.

Conclusion:This case series demonstrates that it is important to keep PTC in the differential diagnosis even when mass lesions such as meningiomas are discovered. Although PTC, as the name indicates, is classically diagnosed in patients without intracranial tumors, it is critical that this not be used as an absolute exclusion criterion. Finally, this case series supports the hypothesis that venous obstruction can result in PTC.

Keywords: Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, meningioma, pseudotumor cerebri, venous outflow obstruction

INTRODUCTION

Pseudotumor cerebri (PTC), which has a prevalence in the general population of 1 to 2 out of 100,000,[

CASE SERIES

Patient 1

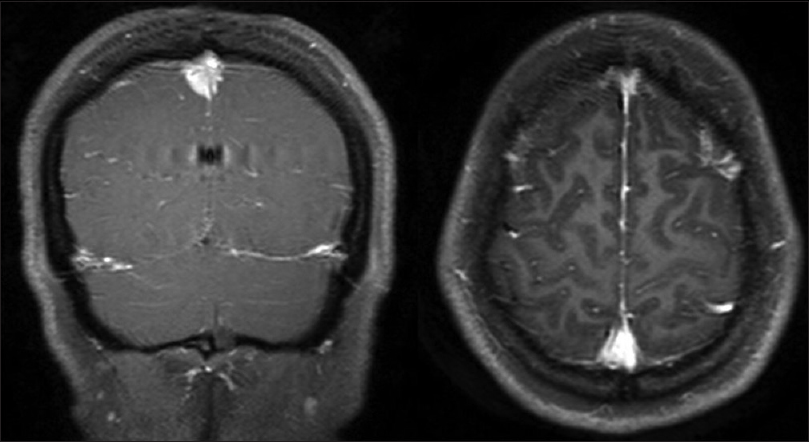

The patient is a 32-year-old woman (body mass index [BMI] of 24.8 kg/m2) with a history of multiple meningiomas. She initially complained of severely painful intermittent headaches that lasted approximately 20 seconds. Over the course of a year, these headaches increased in frequency to multiple times per day. Workup of the headaches at an outside hospital (OSH) included a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that demonstrated multiple lesions, mostly like meningiomas. One of the masses exerted mass effect on the superior sagittal sinus [

Patient 2

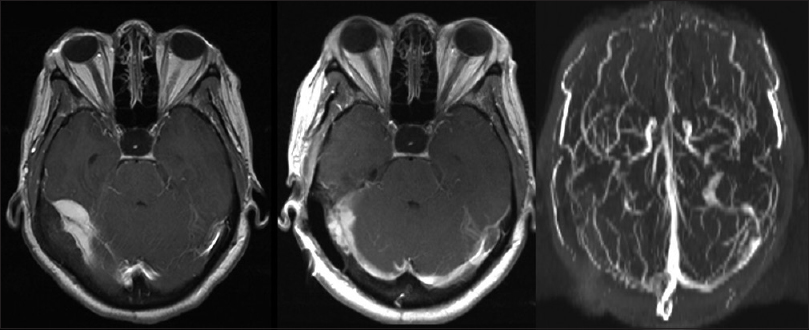

The patient is a 40-year-old woman (BMI of 31.31 kg/m2) with history of meningioma causing partial obstruction of the right transverse sigmoid sinus, with no evidence of hydrocephalus [

Figure 2

Left/middle panels: T1 postcontrast axial MRI demonstrating right temporal/right cerebellar meningioma with mass effect on the right transverse sinus before (left) and after (middle) surgical resection. Some residual was noted along the right transverse sinus. Right panel: Axial MR venogram demonstrating R transverse sinus occlusion

Patient 3

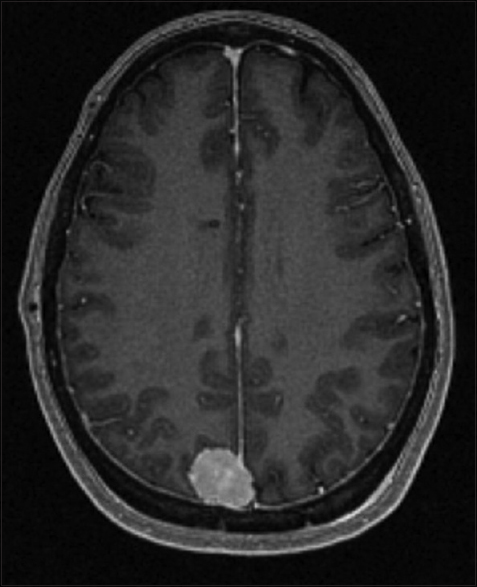

The patient is a 49-year-old woman who presented with left visual field cut (BMI of 27.45 kg/m2). Brain MRI revealed right parieto-occipital meningioma that abutted the superior sagittal sinus without hydrocephalus [

DISCUSSION

Pseudotumor cerebri or idiopathic intracranial hypertension

The term pseudotumor cerebri, which should be differentiated from idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH),[

Symptoms and incidence

The most common symptoms of PTC are headaches, transient visual obscurations (TVOs), pulsatile tinnitus, and ocular pain.[

Diagnosis

Correct and thorough diagnosis is crucial when examining patients with symptoms of PTC. Historically, computer tomography (CT) scans have been used to diagnose intracranial pathology. The advent of magnetic resonance (MR) imaging has greatly improved our ability to detect intracranial pathology.[

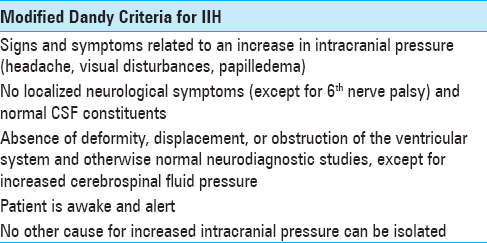

Another important tool used for diagnosis is the Modified Dandy Criteria, which uses a set of criteria to exclude alternative diagnosis similar to PTC.[

Management of care

Once diagnosed, a treatment plan must be formulated. Although there is no single treatment option for PTC, there are three forms of management (surgical management, medical management, and life style change—namely weight reduction) which aim for symptom resolution through a reduction of CSF production and/or CSF pressure.

Surgical treatment options focus on reducing ICP by diversion of CSF.[

Medical management includes the use of diuretics such as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, which decrease the production of CSF.[

One of the most important treatments for PTC, however, is the life style change. Specifically, weight management is critical, especially in obese women. Some studies show that a significant decrease in weight resolves major symptoms such as papilledema and headaches.[

Pathophysiology of PTC

Although the exact mechanism to PTC is still under debate, there have been several potential mechanisms documented in the literature, and decreased CSF absorption is the most commonly proposed mechanism.[

Meningiomas and PTC

The patients described in this case series met the clinical criteria for PTC and symptomatically improved with CSF diversion. Unique to this case series was the presence of meningiomas in these patients. While the vast majority of PTC patients do not have focal lesions on imaging (and although many include this in the diagnostic criteria), this case series demonstrates that patients with benign mass lesions can have PTC. Primary treatment of the meningioma, as was performed in Patient 1, will not resolve the underlying problem. While headache can be a symptom of meningioma, the actual cause of the headache should be investigated further as was performed in Patients 2 and 3. Only after the treatment of the true underlying pathology, PTC, did this patient's condition improve. In this case series, it was interesting to note that only one patient had a BMI over 30 kg/m2 (Patient 2, BMI of 31.8 kg/m2). The other two patients (Patients 1 and 3) had a BMI of 24.8 kg/m2 and 27.44 kg/m2, respectively. No other risk factors were documented. Each patient in this case series had a meningioma that abutted a sinus and resulted in obstruction of venous outflow. Patient 2 underwent MR venogram that definitively demonstrated obstruction of venous outflow in the right transverse sinus [

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, although the prevalence of PTC is quite low in the general population (1 to 2 cases out of 100,000), the strongest incidence is in females who are overweight and at the child-bearing age (19.3 cases per 100,000 in this population). This case series demonstrates that it is important to keep PTC in the differential diagnosis even when mass lesions such as meningiomas are discovered. While PTC, as the name indicates, is classically diagnosed in patients without intracranial tumors, it is critical that this not be used as an absolute exclusion criterion. Furthermore, this case series demonstrates that venous outflow obstruction is a likely cause of PTC.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. . A Rare presentation of neurobrucellosis in a child with Recurrent transient ischemic attacks and pseudotumor cerebri (A case report and review of literature). Iran J Child Neurol. 2014. 8: 65-9

2. Bandyopadhyay S, Jacobson DM. Clinical features of late-onset pseudotumor cerebri fulfilling the modified dandy criteria. J Neuroophthalmol. 2002. 22: 9-11

3. Chutorian A. Reactivation of varicella presenting as pseudotumor cerebri: Three cases and a review of the literature. Pediatr Neurol. 2012. 46: 335-

4. Daniels AB, Liu GT, Volpe NJ, Galetta SL, Moster ML, Newman NJ. Profiles of obesity, weight gain, and quality of life in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Am J Ophthalmol. 2007. 143: 635-41

5. De Simone R, Ranieri A, Montella S, Friedman DI, Liu GT, Digre KB. Revised diagnostic criteria for the pseudotumor cerebri syndrome in adults and children. Neurology. 2014. 82: 1011-2

6. Degnan AJ, Levy LM. Pseudotumor cerebri: Brief review of clinical syndrome and imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011. 32: 1986-93

7. Durcan FJ, Corbett JJ, Wall M. The incidence of pseudotumor cerebri. Population studies in Iowa and Louisiana. Arch Neurol. 1988. 45: 875-7

8. Evans RW, Friedman DI. Expert opinion: The management of pseudotumor cerebri during pregnancy. Headache. 2000. 40: 495-7

9. Farb RI, Vanek I, Scott JN, Mikulis DJ, Willinsky RA, Tomlinson G. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: The prevalence and morphology of sinovenous stenosis. Neurology. 2003. 60: 1418-24

10. Friedman DI. Pseudotumor cerebri. Neurol Clin. 2004. 22: 99-131

11. Friedman DI. The pseudotumor cerebri syndrome. Neurol Clin. 2014. 32: 363-6

12. Friedman DI, Liu GT, Digre KB. Revised diagnostic criteria for the pseudotumor cerebri syndrome in adults and children. Neurology. 2013. 81: 1159-65

13. Giuseffi V, Wall M, Siegel PZ, Rojas PB. Symptoms and disease associations in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri): A case-control study. Neurology. 1991. 41: 239-44

14. Hainline C, Rucker JC, Balcer LJ. Current concepts in pseudotumor cerebri. Curr Opin Neurol. 2016. 29: 84-93

15. Higgins JN, Cousins C, Owler BK, Sarkies N, Pickard JD. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: 12 cases treated by venous sinus stenting. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003. 74: 1662-6

16. Higgins JN, Gillard JH, Owler BK, Harkness K, Pickard JD. MR venography in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: Unappreciated and misunderstood. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004. 75: 621-5

17. Kan L, Sood SK, Maytal J. Pseudotumor cerebri in Lyme disease: A case report and literature review. Pediatr Neurol. 1998. 18: 439-41

18. Kanagalingam S, Subramanian PS. Cerebral venous sinus stenting for pseudotumor cerebri: A review. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2015. 29: 3-8

19. Kesler A, Goldhammer Y, Gadoth N. Do men with pseudomotor cerebri share the same characteristics as women?. A retrospective review of 141 cases. J Neuroophthalmol. 2001. 21: 15-7

20. Kravitz J, Frankel R. Head trauma-induced pseudotumor cerebri--a case report and review. J Trauma. 2010. 68: E91-3

21. Levine DN. Ventricular size in pseudotumor cerebri and the theory of impaired CSF absorption. J Neurol Sci. 2000. 177: 85-94

22. Liguori C, Romigi A, Albanese M, Marciani MG, Placidi F, Friedman D. Revised diagnostic criteria for the pseudotumor cerebri syndrome in adults and children. Neurology. 2014. 82: 1752-3

23. Mallery RM, Friedman DI, Liu GT. Headache and the pseudotumor cerebri syndrome. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014. 18: 446-

24. McGeeney BE, Friedman DI. Pseudotumor cerebri pathophysiology. Headache. 2014. 54: 445-58

25. Meredith JM. The elimination of non-surgical lesions in brain tumor suspects; pseudo-tumor cerebri, and papilledema without increased intracranial pressure (optic neuritis). South Med J. 1948. 41: 31-7

26. Mokri B, Jack CR, Petty GW. Pseudotumor syndrome associated with cerebral venous sinus occlusion and antiphospholipid antibodies. Stroke. 1993. 24: 469-72

27. Pearce JM. From pseudotumour cerebri to idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Pract Neurol. 2009. 9: 353-6

28. Peterson CM, Kelly JV. Pseudotumor cerebri in pregnancy. Case reports and review of literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1985. 40: 323-9

29. Ravid S, Shachor-Meyouhas Y, Shahar E, Kra-Oz Z, Kassis I. Reactivation of varicella presenting as pseudotumor cerebri: Three cases and a review of the literature. Pediatr Neurol. 2012. 46: 124-6

30. Rowe FJ, Sarkies NJ. Assessment of visual function in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: A prospective study. Eye (Lond). 1998. 12: 111-8

31. Silberstein SD, McKinstry RC. The death of idiopathic intracranial hypertension?. Neurology. 2003. 60: 1406-7

32. Suttajit S, Wagner AK, Tantipidoke R, Ross-Degnan D, Sitthi-amorn C. Patterns, appropriateness, and predictors of antimicrobial prescribing for adults with upper respiratory infections in urban slum communities of Bangkok. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005. 36: 489-97

33. Sylaja PN, Ahsan Moosa NV, Radhakrishnan K, Sankara Sarma P, Pradeep Kumar S. Differential diagnosis of patients with intracranial sinus venous thrombosis related isolated intracranial hypertension from those with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Sci. 2003. 215: 9-12

34. Szitkar B. A meningioma exclusively located inside the superior sagittal sinus responsible for intracranial hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010. 31: E57-8

35. Tasdemir HA, Dilber C, Totan M, Onder A. Pseudotumor cerebri complicating measles: A case report and literature review. Brain Dev. 2006. 28: 395-7

36. Venable HP. Pseudo-tumor cerebri. J Natl Med Assoc. 1970. 62: 435-40

37. Venable HP. Pseudo-tumor cerebri: Further studies. J Natl Med Assoc. 1973. 65: 194-7

38. Walker RW. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: Any light on the mechanism of the raised pressure?. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001. 71: 1-5

39. Wall M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurol Clin. 2010. 28: 593-617

40. Wall M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurol Clin. 1991. 9: 73-95

41. Wall M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension and the idiopathic intracranial hypertension treatment trial. J Neuroophthalmol. 2013. 33: 1-3

42. Wall M, George D. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. A prospective study of 50 patients. Brain. 1991. 114: 155-80