- Department of Surgical Neurology, Research Institute for Brain and Blood Vessels-AKITA, 6-10 Senshu-Kubota-Machi, Akita, Japan

Correspondence Address:

Jun Tanabe

Department of Surgical Neurology, Research Institute for Brain and Blood Vessels-AKITA, 6-10 Senshu-Kubota-Machi, Akita, Japan

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.143362

Copyright: © 2014 Tanabe J. This is an open-ccess article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.How to cite this article: Tanabe J, Moroi J, Yoshioka S, Ishikawa T. Recanalization of a ruptured vertebral artery dissecting aneurysm after occlusion of the dilated segment only. Surg Neurol Int 21-Oct-2014;5:150

How to cite this URL: Tanabe J, Moroi J, Yoshioka S, Ishikawa T. Recanalization of a ruptured vertebral artery dissecting aneurysm after occlusion of the dilated segment only. Surg Neurol Int 21-Oct-2014;5:150. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/recanalization-of-a-ruptured-vertebral-artery-dissecting-aneurysm-after-occlusion-of-the-dilated-segment-only/

Abstract

Background:Internal trapping in which the dissecting aneurysm is occluded represents reliable treatment to prevent rebleeding of ruptured vertebral artery (VA) dissecting aneurysms. Various methods of internal trapping are available, but which is most appropriate for preventing both recanalization of the VA and procedural complications is unclear.

Case Description:A 61-year-old male presented with subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by rupture of a left VA dissecting aneurysm. Only the dilated segment of the aneurysm was occluded by coil embolization. Sixteen days after embolization, angiography showed recanalization of the treated left VA with blood supplying the dilated segment of the aneurysm, which showed morphological change between just proximal to the coil mesh and just distal to a coil, and antegrade blood flow through this part. Pathological examination showed that the rupture site that had appeared to be the most dilated area on angiography was located just above the orifice of the entrance. However, we think that this case of ruptured aneurysm had an entrance into a pseudolumen that existed proximal to the dilated segment, with antegrade recanalization occurring through the pseudolumen with morphological change because of insufficient coil obliteration of the entrance in the first therapy.

Conclusions:This case suggests that occlusion of both the proximal and dilated segments of a VA dissecting aneurysm will prevent recanalization, by ensuring that any entrance to a pseudolumen of the aneurysm is completely closed. Careful follow-up after internal trapping is important, since antegrade recanalization via a pseudolumen may occur in the acute stage.

Keywords: Dissecting aneurysm, internal trapping, recanalization, subarachnoid hemorrhage

INTRODUCTION

Vertebral artery (VA) dissecting aneurysms often cause subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). A high incidence of rebleeding is seen during the acute phase, particularly within 24 h from onset, and is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates.[

Endovascular treatment has been widely applied to VA dissecting aneurysms, because these procedures are quicker and less invasive than direct surgery.[

Various methods are available for internal trapping, including occlusion of the dilated segment of the aneurysm and distal and proximal VA, occlusion of the dilated segment of the aneurysm and proximal VA, and occlusion of the dilated segment of the aneurysm only.[

We report herein a case of antegrade VA recanalization without obvious coil compaction after internal trapping for acute-phase occlusion of only a dilated segment of the aneurysm.

CASE REPORT

A 61-year-old male without any noteworthy medical history presented with sudden severe headache (World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies grade II). Computed tomography (CT) revealed SAH, which was particularly prominent in the posterior fossa (Fisher group 3). Subsequent CT angiography revealed dissecting aneurysm of the left VA arising distal to the origin of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA). Both VAs were co-dominant.

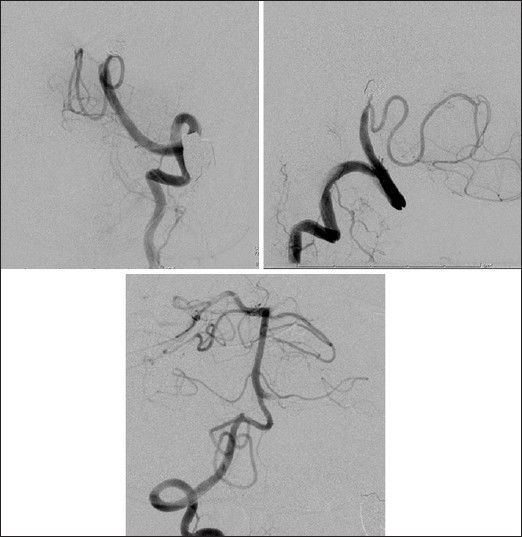

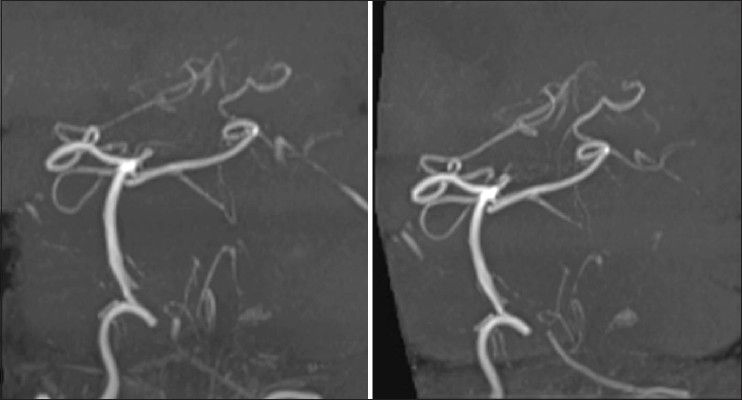

Endovascular treatment under general anesthesia was performed immediately after diagnostic angiography [

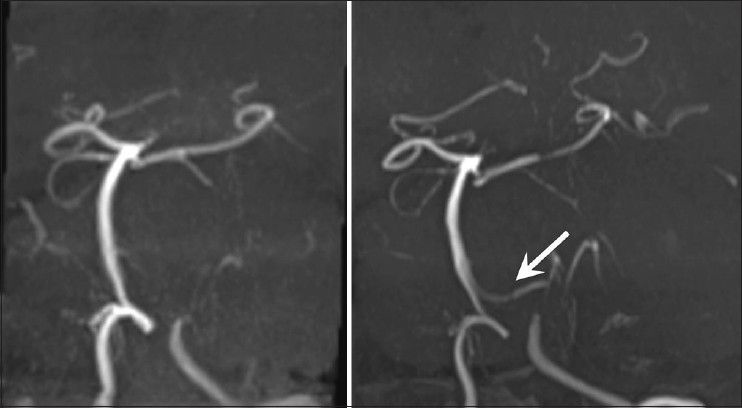

The patient showed good recovery from general anesthesia and his consciousness was clear. Posttreatment clinical course seemed uneventful. However, 16 days after embolization, routine follow-up magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) performed to ascertain improvement of cerebral vasospasm showed suspected recanalization of the aneurysm because of newly apparent flow in the left VA distal to the aneurysm in comparison with the examination on day 1 after the first operation [

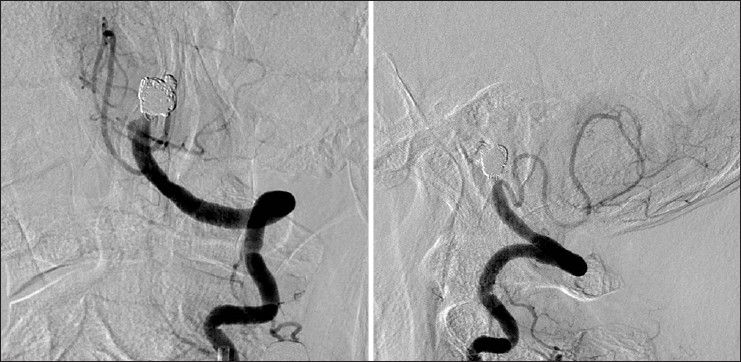

Further endovascular treatment was performed under local anesthesia, occluding the dilated segment of aneurysm, which showed morphological changes and the segment of the left VA proximal to the dilated segment [

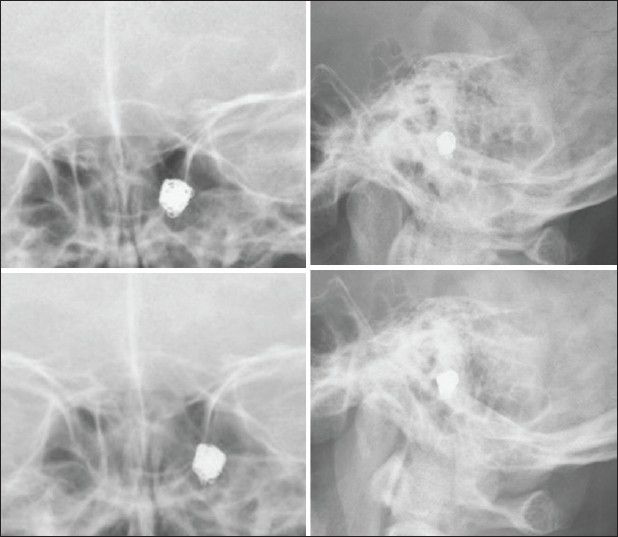

Figure 4

Anteroposterior (upper left) and lateral (upper right) left VA angiograms, and the 3-dimensional reconstruction image (lower) obtained 16 days after first operation, revealing recanalization of the treated left VA with blood supplying the dilated segment of the aneurysm showing morphological change and antegrade flow into the BA through the part where the morphology had changed, not through the dilated segment of aneurysm

Figure 6

Anteroposterior (left) and lateral (right) left VA angiograms after additional coil embolization demonstrate complete obliteration of the aneurysm and affected left VA with preservation of the left PICA. The pseudolumen was mainly occluded after a microcatheter was navigated into the pseudolumen via the entrance in additional endovascular treatment

DISCUSSION

In the present case, we performed internal trapping for ruptured VA dissecting aneurysms in the acute stage. This first treatment occluded only the dilated segment of the aneurysm, followed by recanalization of the occluded VA in antegrade fashion after 16 days. Antegrade recanalization flow occurred in the lateral compartment of first coil embolization, which was accompanied by morphological change. Antegrade blood flow was provided from proximal to distal to the coil mass, not through the region of first coil embolization. Recanalization of a coil-occluded VA is a well-known endovascular phenomenon.[

Sawada et al. first reported recanalization of VA aneurysms during follow-up (3-6 months) for two cases of ruptured VA dissecting aneurysms treated using internal trapping.[

On pathological examination, the majority of aneurysms show one entrance into the pseudolumen (entry-only type).[

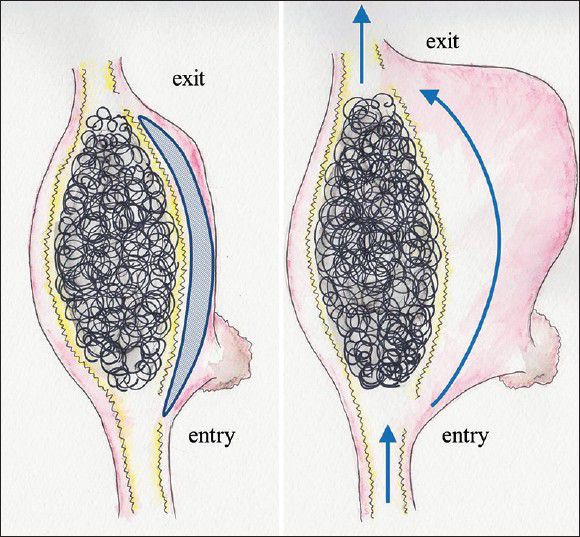

Figure 8

(Left) First operation for entry-exit VA dissecting aneurysm in this case. Oblique line pattern represents intramural clot. (Right) Recanalization of the aneurysm showing morphological change 16 days after postoperatively. Wavy line represents the internal elastic laminar. Arrows demonstrates blood flow through the pseudolumen

We suggest that occlusion of the proximal segment as well as the dilated segment of a VA dissecting aneurysm will prevent recanalization by definitively occluding the entrance to the aneurysm pseudolumen. We do not know preoperatively whether a ruptured VA dissecting aneurysm represents the entry-only or entry-exit type, and high blood pressure from antegrade flow across the entrance to a pseudolumen may cause recanalization if only the dilated segment is occluded for ruptured entry-exit cerebral dissecting aneurysms as in the present case. We think that additional occlusion of the distal VA should not be performed, because occlusion of the distal VA before the dilated segment of the aneurysm risks causing intraoperative rupture owing to high blood pressure directly on the dilated segment. In addition, there is a risk of ischemic complications associated with occlusion of the perforators arising from the VA near the vertebral basilar junction, especially in VA dissecting aneurysms distal to the origin of the PICA.[

Occlusion of only the dilated segment of the aneurysm to preserve the PICA and conduct prompt prevention of rerupture in the first treatment may cause antegrade recanalization via a pseudolumen in the acute stage owing to the same mechanisms as in the present case. Accordingly, careful follow-up with angiography and MRA is required, and open surgical clip trapping of the affected VA and creation of a PICA bypass should be considered as an additional treatment.

CONCLUSION

Based on this unique case, we suggest that occlusion of the proximal segment as well as the dilated segment of a VA dissecting aneurysm showing no hypoplasia of the contralateral VA will prevent recanalization, by ensuring that any entrance to a pseudolumen of the aneurysm is completely closed. However, further studies are needed to assess the radical and safety of internal trapping, as a single case, is inadequate to draw solid conclusions from. Careful follow-up after internal trapping, especially only obliteration of dilated segment, is important since antegrade recanalization via a pseudolumen may occur in the acute stage.

References

1. Ihn YK, Sung JH, Byun JH. Antegrade recanalization of parent artery after internal trapping of ruptured vertebral artery dissecting aneurysm. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012. 51: 301-4

2. Iihara K, Sakai N, Murao K, Sakai H, Higashi T, Kogure S. Dissecting aneurysms of the vertebral artery: A management strategy. J Neurosurg. 2002. 97: 259-67

3. Jin SC, Kwon DH, Choi CG, Ahn JS, Kwun BD. Endovascular strategies for vertebrobasilar dissecting aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009. 30: 1518-23

4. Kojima A, Okui S, Onozuka S. Long-term follow up of antegrade recanalization of vertebral artery dissecting aneurysm after internal trapping: Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2010. 50: 910-3

5. Mahmood A, Dujovny M, Torche M, Dragovic L, Ausman JI. Microvascular anatomy of foramen caecum medullae oblongatae. J Neurosurg. 1991. 75: 299-304

6. Mizutani T, Aruga T, Kirino T, Miki Y, Saito I, Tsuchida T. Recurrent subarachnoid hemorrhage from untreated ruptured vertebrobasilar dissecting aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1995. 36: 905-13

7. Mizutani T, Kojima H, Asamoto S, Miki Y. Pathological mechanism and three-dimensional structure of cerebral dissecting aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2001. 94: 712-7

8. Rabinov JD, Hellinger FR, Morris PP, Ogilvy CS, Putman CM. Endovascular management of vertebrobasilar dissecting aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003. 24: 1421-8

9. Ro A, Kageyama N. Pathomorphometry of ruptured intracranial vertebral arterial dissection: Adventitial rupture, dilated lesion, intimal tear, and medial defect. J Neurosurg. 2013. 119: 221-7

10. Sawada M, Kaku Y, Yoshimura S, Kawaguchi M, Matsuhisa T, Hirata T. Antegrade recanalization of a completely embolized vertebral artery after endovascular treatment of a ruptured intracranial dissecting aneurysm. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 2005. 102: 161-6

11. Sugiu K, Tokunaga K, Ono S, Nishida A, Date I. Rebleeding from a vertebral artery dissecting aneurysm after endovascular internal trapping: Adverse effect of intrathecal urokinase injection or incomplete occlusion?-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2009. 49: 597-600

12. Wong GK, Tang HB, Poon WS, Yu SC. Treatment of ruptured intracranial dissecting aneurysms in Hong Kong. Surg Neurol Int. 2010. 1: 84-

13. Yamaura I, Tani E, Yokota M, Nakano A, Fukami M, Kaba K. Endovascular treatment of ruptured dissecting aneurysms aimed at occlusion of the dissected site by using Guglielmi detachable coils. J Neurosurg. 1999. 90: 853-6